Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler was a political major general of the Union Army during the American Civil War and had a leadership role in the impeachment of U.S. president Andrew Johnson. He was a colorful and often controversial figure on the national stage and on the Massachusetts political scene, serving five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and running several campaigns for governor before his election to that office in 1882.

Benjamin Butler | |

|---|---|

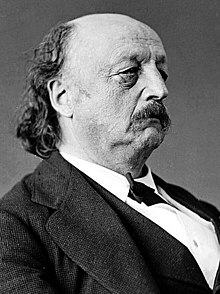

Butler c. 1870–80 | |

| 33rd Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 4, 1883 – January 3, 1884 | |

| Lieutenant | Oliver Ames |

| Preceded by | John Long |

| Succeeded by | George D. Robinson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1879 | |

| Preceded by | John K. Tarbox |

| Succeeded by | William A. Russell |

| Constituency | 7th district |

| In office March 4, 1867 – March 4, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | John B. Alley |

| Succeeded by | Charles Perkins Thompson |

| Constituency | 6th district (1867–1873) 7th district (1873–1875) |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate | |

| In office 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Arthur Bonney |

| Succeeded by | Ephraim Patch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Benjamin Franklin Butler November 5, 1818 Deerfield, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | January 11, 1893 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Hildreth Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Other political affiliations | Greenback (1874–1889) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4, including Blanche |

| Education | Colby College (BA) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

Butler, a successful trial lawyer, served in the Massachusetts legislature as an antiwar Democrat and as an officer in the state militia. Early in the Civil War he joined the Union Army, where he was noted for his lack of military skill and his controversial command of New Orleans, which made him widely disliked in the South and earned him the "Beast" epithet. Although freeing an enemy's slaves had occurred in previous wars, Butler came up with the idea of doing so by designating them as contraband of war,[1] an idea that the Lincoln administration endorsed and that played a role in making emancipation an official war goal. His commands were marred by financial and logistical dealings across enemy lines, some of which may have taken place with his knowledge and to his financial benefit.

Butler was dismissed from the Union Army after his failures in the First Battle of Fort Fisher, but he soon won election to the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts. As a Radical Republican he considered President Johnson's Reconstruction agenda to be too weak, advocating harsher punishments of former Confederate leadership and stronger stances on civil rights reform. He was also an early proponent of the prospect of impeaching Johnson. After Johnson was impeached in early 1868, Butler served as the lead prosecutor among the House-appointed impeachment managers in the Johnson impeachment trial proceedings. Additionally, as Chairman of the House Committee on Reconstruction, Butler authored the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 and coauthored the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1875.

In Massachusetts, Butler was often at odds with more conservative members of the political establishment over matters of both style and substance. Feuds with Republican politicians led to his being denied several nominations for the governorship between 1858 and 1880. Returning to the Democratic fold, he won the governorship in the 1882 election with Democratic and Greenback Party support. He ran for president on the Greenback Party and the Anti-Monopoly Party tickets in 1884.

Early years

editBenjamin Franklin Butler was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire, the sixth and youngest child of John Butler and Charlotte Ellison Butler. His father served under General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812 and later became a privateer, dying of yellow fever in the West Indies not long after Benjamin was born.[2] He was named after Founding Father Benjamin Franklin. His elder brother, Andrew Jackson Butler (1815–1864), served as a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War and joined him in New Orleans.[3] Butler's mother was a devout Baptist who encouraged him to read the Bible and prepare for the ministry.[2] In 1827, at the age of nine, Butler was awarded a scholarship to Phillips Exeter Academy, where he spent one term. He was described by a schoolmate as "a reckless, impetuous, headstrong boy", and regularly got into fights.[4]

Butler's mother moved the family in 1828 to Lowell, Massachusetts, where she operated a boarding house for workers at the textile mills. He attended the public schools there, from which he was almost expelled for fighting, the principal describing him as a boy who "might be led, but could not be driven."[5] He attended Waterville (now Colby) College in pursuit of his mother's wish that he prepare for the ministry, but eventually rebelled against the idea. In 1836, Butler sought permission to go instead to West Point for a military education, but he did not receive one of the few places available. He continued his studies at Waterville, where he sharpened his rhetorical skills in theological discussions and began to adopt Democratic Party political views. He graduated in August 1838.[6] Butler returned to Lowell, where he clerked and read law as an apprentice with a local lawyer. He was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1840 and opened a practice in Lowell.[7]

After an extended courtship, Butler married Sarah Hildreth, a stage actress and daughter of Dr. Israel Hildreth of Lowell, on May 16, 1844. They had four children: Paul (1845–1850), Blanche (1847–1939), Paul (1852–1918) and Ben-Israel (1855–1881).[8] Butler's business partners included Sarah's brother Fisher, and her brother-in-law, W. P. Webster.[9]

In 1844, Butler was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.[10]

Law and early business dealings

editButler quickly gained a reputation as a dogged criminal defense lawyer who seized on every misstep of his opposition to gain victories for his clients, and also became a specialist in bankruptcy law.[7] His trial work was so successful that it received regular press coverage, and he was able to expand his practice into Boston.[11] George Riley worked at his Boston law office.[12]

Butler's success as a lawyer enabled him to purchase shares in Lowell's Middlesex Mill Company when they were cheap.[13] Although he generally represented workers in legal actions, he also sometimes represented mill owners. This adoption of both sides of an issue manifested itself when he became more politically active. He first attracted general attention by advocating the passage of a law establishing a ten-hour day for laborers,[14] but he also opposed labor strikes over the matter. He instituted a ten-hour work day at the Middlesex Mills.[15]

Pre-Civil War political career

editDuring the debates over the ten-hour day a Whig-supporting Lowell newspaper published a verse suggesting that Butler's father had been hanged for piracy. Butler sued the paper's editor and publisher for that and other allegations that had been printed about himself. The editor was convicted and fined $50, but the publisher was acquitted on a technicality. Butler blamed the Whig judge, Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, for the acquittal, inaugurating a feud between the two that would last for decades and significantly color Butler's reputation in the state.[16]

Butler, as a Democrat, supported the Compromise of 1850 and regularly spoke out against the abolition of slavery. At the state level, he supported the coalition of Democrats and Free Soilers that elected George S. Boutwell governor in 1851. This garnered him enough support to win election to the state legislature in 1852.[15] His support for Franklin Pierce as president, however, cost him the seat the next year. He was elected a delegate to the 1853 state constitutional convention with strong Catholic support, and was elected to the state senate in 1858, a year dominated by Republican victories in the state.[17] Butler was nominated for governor in 1859 and ran on a pro-slavery, pro-tariff platform. He lost to incumbent Republican Nathaniel Prentice Banks.[13][18]

In the 1860 Democratic National Convention at Charleston, South Carolina, Butler initially supported John C. Breckinridge for president but then shifted his support to Jefferson Davis, believing that only a moderate Southerner could keep the Democratic party from dividing. A conversation he had with Davis prior to the convention convinced him that Davis might be such a man, and he gave him his support before the convention split over slavery.[19] Butler ended up supporting Breckinridge over Douglas against state party instructions, ruining his standing with the state party apparatus. He was nominated for governor in the 1860 election by a Breckinridge splinter of the state party, but trailed far behind other candidates.[20]

Civil War

editAlthough he sympathized with the South, Butler stated, "I was always a friend of southern rights but an enemy of southern wrongs" and sought to serve in the Union Army.[21] His military career before the Civil War began as a private in the Lowell militia in 1840.[22] Butler eventually rose to become colonel of a regiment of primarily Irish American men. In 1855, the nativist Know Nothing governor Henry J. Gardner disbanded Butler's militia, but Butler was elected brigadier general after the militia was reorganized. In 1857 Secretary of War Jefferson Davis appointed him to the Board of Visitors of West Point.[23] These positions did not give him any significant military experience.[24]

1860

editAfter Abraham Lincoln was elected president in November 1860, Butler traveled to Washington, D.C. When a secessionist South Carolina delegation arrived there he recommended to lameduck President James Buchanan that they be arrested and charged with treason. Buchanan rejected the idea. Butler also met with Jefferson Davis and learned that he was not the Union man that Butler had previously thought he was. Butler then returned to Massachusetts,[25] where he warned Governor John A. Andrew that hostilities were likely and that the state militia should be readied. He took advantage of the mobilization to secure a contract with the state for his mill to supply heavy cloth to the militia. Military contracts would constitute a significant source of profits for Butler's mill throughout the war.[26]

Petitioning for military leadership appointment

editButler also worked to secure a leadership position should the militia be deployed. He first offered his services to Governor Andrew in March 1861.[26] When the call for militia finally arrived in April, Massachusetts was asked for only three regiments, but Butler managed to have the request expanded to include a brigadier general. He telegraphed Secretary of War Simon Cameron, with whom he was acquainted, suggesting that Cameron issue a request for a brigadier and general staff from Massachusetts, which soon afterward appeared on Governor Andrew's desk. He then used banking contacts to ensure that loans that would be needed to fund the militia operations would be conditioned on his appointment. Despite Andrew's desire to assign the brigadier position to Ebenezer Peirce, the bank insisted on Butler, and he was sent south to ensure the security of transportation routes to Washington.[27][28] The nation's capital was threatened with isolation from free states because it was unclear whether Maryland, a slave state, would also secede.[29]

1861: Baltimore and Virginia operations

editThe two regiments Massachusetts sent to Maryland were the 6th and 8th Volunteer Militia. The 6th departed first and was caught up in a secessionist riot in Baltimore, Maryland on April 19. Butler traveled with the 8th, which left Philadelphia the next day amid news that railroad connections around Baltimore were being severed.[30] Butler and the 8th traveled by rail and ferry to Maryland's capital, Annapolis, where Governor Thomas H. Hicks attempted to dissuade them from landing.[31] Butler landed his troops (who needed food and water), occupying the Naval Academy. When Hicks informed Butler that no one would sell provisions to his force, Butler pointed out that armed men did not necessarily have to pay for needed provisions, and he would use all measures necessary to ensure order.[32]

After being joined by the 7th New York Militia, Butler directed his men to restore rail service between Annapolis and Washington via Annapolis Junction,[33] which was accomplished by April 27. He also threatened Maryland legislators with arrest if they voted in favor of secession, and he seized the Great Seal of Maryland, "without which no legislation could become law."[34] Butler's prompt actions in securing Annapolis were received with approval by the US Army's top general, Winfield Scott, and he was given formal orders to maintain the security of the transit links in Maryland.[35] In early May, Scott ordered Butler to lead the operations that occupied Baltimore. On May 13 he entered Baltimore on a train with 1000 men and artillery, with no opposition.[36] That was done in contravention of Butler's orders from Scott, which had been to organize four columns to approach the city by land and sea. General Scott criticized Butler for his strategy (despite its success) as well as his heavy-handed assumption of control of much of the civil government, and he recalled him to Washington.[37] Butler shortly after received one of the early appointments as major general of the volunteer forces.[29] His exploits in Maryland also brought nationwide press attention, including significant negative press in the South, which concocted stories about him that were conflations of biographical details involving not just Butler but also a namesake from New York and others.[38]

Fort Monroe, Virginia

editWhen two Massachusetts regiments had been sent overland to Maryland, two more were dispatched by sea under Butler's command to secure Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James River.[29] After being dressed down by Scott for overstepping his authority, Butler was next assigned command of Fort Monroe and of the Department of Virginia.[39] On May 27, Butler sent a force 8 miles (13 km) north to occupy the lightly defended adjacent town of Newport News, Virginia at Newport News Point, an excellent anchorage for the Union Navy. The force established and significantly fortified Camp Butler and a battery at Newport News Point that could cover the entrance to the James River ship canal and the mouth of the Nansemond River. Butler also expanded Camp Hamilton, established in the adjacent town of Hampton, Virginia, just beyond the confines of the fort and within the range of its guns.[40]

The Union occupation of Fort Monroe was considered a threat to Richmond by Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and he began organizing the defense of the Virginia Peninsula in response.[41] Confederate General John B. Magruder, seeking to buy time while awaiting men and supplies, established well-defended forward outposts near Big and Little Bethel, only 8 miles (13 km) from Butler's camp at Newport News as a lure to draw his opponent into a premature action.[42] Butler took the bait, and suffered an embarrassing defeat at the Battle of Big Bethel on June 10. Butler devised a plan for a night march and operation against the positions but chose not to lead the force in person, for which he was criticized.[43] The plan proved too complex for his inadequately trained subordinates and troops to carry out, especially at night, and was further marred by the failure of staff to communicate passwords and precautions. A friendly fire incident during the night gave away the Union position, further harming the advance, which was attempted without knowledge of the layout or the strength of the Confederate positions.[44] Massachusetts militia general Ebenezer W. Peirce, who commanded in the field, received the most criticism for the failed operation.[45] With the withdrawal of many of his men for use elsewhere, Butler was unable to maintain the camp at Hampton, although his forces retained the camp at Newport News.[46] Butler's commission, which required approval from Congress, was vigorously debated after Big Bethel, with critical comment raised about his lack of military experience. But his commission was narrowly approved on July 21, the day of the First Battle of Bull Run, the war's first large-scale battle.[47] The battle's poor outcome for the Union was used as cover by General Scott to reduce Butler's force to one incapable of substantive offense, and it was implicit in Scott's orders that the troops were needed nearer to Washington.[48]

In August, Butler commanded an expeditionary force that, in conjunction with the United States Navy, took Forts Hatteras and Clark in North Carolina. That move, the first significant Union victory after First Bull Run, was lauded in Washington and won Butler accolades from President Lincoln. Butler was sent back to Massachusetts to raise new forces.[49] That thrust Butler into a power struggle with Governor Andrew, who insisted on maintaining his authority to appoint regimental officers, refusing to commission (among others) Butler's brother Andrew and several of the general's close associates. The spat instigated a recruiting war between Butler and the state militia organization.[50] The dispute delayed Butler's return to Virginia, and in November he was assigned to command ground troops in Louisiana.[51]

While in command at Fort Monroe, Butler had declined to return to their owners fugitive slaves who had come within his lines. He argued that Virginians considered them to be chattel property, and that they could not appeal to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 because of Virginia's secession. "I am under no constitutional obligations to a foreign country," he said, "which Virginia now claims to be."[52] Furthermore, slaves used as laborers for building fortifications and other military activities could be considered contraband of war.[53][54] "Lincoln and his Cabinet discussed the issue on May 30 and decided to support Butler's stance".[55] It was later made standard Union Army policy to not return fugitive slaves.[56] This policy was soon extended to the Union Navy.[57]

New Orleans

editButler directed the first Union expedition to Ship Island, off the Mississippi Gulf Coast, in December 1861,[58] and in May 1862 commanded the force that conducted the capture of New Orleans after its occupation by the Navy following the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. In the administration of that city he showed great firmness and political subtlety. He devised a plan for relief of the poor, demanded oaths of allegiance from anyone who sought any privilege from government, and confiscated weapons.[21]

However, Butler's subtlety seemed to fail him as the military governor of New Orleans when it came to dealing with its Jewish population, about which the general, referring to local smugglers, infamously wrote, in October 1862: "They are Jews who betrayed their Savior, & also have betrayed us."[59]

Public health management

editIn an ordinary year, it was not unusual for as much as 10 percent of the city's population to die of yellow fever. In preparation, Butler imposed strict quarantines and introduced a rigid program of garbage disposal. As a result, in 1862, only two cases were reported.[60]

Civil administration difficulties

editMany of his acts, however, were highly unpopular. Most notorious was Butler's General Order No. 28 of May 15, 1862, that if any woman should insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she may be treated similarly to a "woman of the town plying her avocation," i.e., a prostitute.[61] This was in response to various acts of verbal and physical abuse inappropriate of "respectable" women, including mocking the funeral cortège of a fallen soldier, spitting in the faces of U.S. officers, pouring chamber pots full of human excrement on patrolling U.S. soldiers, and, in one notorious case, pouring urine on Admiral David Farragut, the Union Navy commander.[62]

"Butler's 'Woman Order' was immediately effective. Insults by word, look or gesture abruptly ceased.... Throughout the South, however, the Woman Order evoked a universal shout of execration".[63] Butler's insistence on prosecuting the woman as any other person "aiding the Confederacy" provoked angry jeers from white residents of New Orleans, who amplified a narrative that he used his power to engage in the petty looting of New Orleanians.[21] "[F]or years after the Civil War steamships plying the lower Mississippi were furnished with chamber pots bearing the likeness of 'Beast Butler'".[64]

He was nicknamed "Butler the Beast" by Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard (despite Beauregard's leaving his wife under Butler's personal care) or alternatively "Spoons Butler", the latter nickname deriving primarily from an incident in which Butler seized a 38-piece set of silverware from a New Orleans woman who attempted to cross Union lines[65] while using a pass that permitted her to carry nothing more than the clothing on her person.

Cotton seizures

editShortly after the Confiscation Act of 1862 became effective in September, Butler increasingly relied upon it as a means of grabbing cotton. Since the Act permitted confiscation of property owned by anyone "aiding the Confederacy," Butler reversed his earlier policy of encouraging trade by refusing to confiscate cotton brought into New Orleans for sale. First, he conducted a census in which 4,000 respondents failing to pledge loyalty to the Union were banished. Their property was seized and sold at low auction prices in which his brother Andrew was often the prime buyer. Next, the general sent expeditions into the countryside with no military purpose other than to confiscate cotton from residents who were assumed to be disloyal. Once brought into New Orleans, the cotton would be similarly sold in rigged auctions. To maintain correct appearances, auction proceeds were dutifully held for the benefit of "just claimants", but the Butler consortium still ended up owning the cotton at bargain prices. Always inventive of new terminology to achieve his ends, Butler sequestered, or made vulnerable to confiscation, such "properties" in all of Louisiana beyond parishes surrounding New Orleans.[66]

Censorship of newspapers

editButler censored New Orleans newspapers. When William Seymour, the editor of the New-Orleans Commercial Bulletin, asked Butler what would happen if the newspaper ignored his censorship, an angry Butler reportedly stated, "I am the military governor of this state — the supreme power — you cannot disregard my order, Sir. By God, he that sins against me, sins against the Holy Ghost." When Seymour published a favorable obituary of his father, who had been killed serving in the Confederate army in Virginia, Butler confiscated the newspaper and imprisoned Seymour for three months.[21]

Execution of William Mumford

editOn June 7, 1862, Butler ordered the execution of William B. Mumford for tearing down a United States flag placed by Admiral Farragut on the United States Mint in New Orleans. In his memoirs, Butler maintained that "[a] party headed by Mumford had torn down the flag, dragged it through the streets and spit on it, and trampled on it until it was torn to pieces. It was then distributed among the rabble, and each one thought it a high honor to get a piece of it and wear it." Butler added that these actions were "against the laws of war and his country."[67]

Before Mumford was executed, Butler permitted him to make a speech for as long as he wished, and Mumford defended his actions by claiming that he was acting out of a high sense of patriotism.[68] Most, including Mumford and his family, expected Butler to pardon him. The general refused to do so,[69] but promised to care for his family if necessary. (After the war, Butler fulfilled his promise by paying off a mortgage on Mumford's widow's house and helping her find government employment.) For the execution and General Order No. 28, he was denounced (December 1862) by Confederate President Jefferson Davis in General Order 111 as a felon deserving capital punishment, who, if captured, should be "reserved for execution".[70]

Recall

editAlthough Butler's governance of New Orleans was popular in the North, where it was seen as a successful stand against recalcitrant secessionists, some of his actions, notably those against the foreign consuls, concerned Lincoln, who authorized his recall in December 1862.[71] Butler was replaced by Nathaniel P. Banks.[72] The necessity of taking sometimes radical actions and the support he received in Radical Republican circles drove Butler to change political allegiance, and he joined the Republican Party. He also sought revenge against the more moderate Secretary of State Seward, whom he believed to be responsible for his eventual recall.[73]

Butler continues to be a disliked and controversial figure in New Orleans and the rest of the South.[74]

Louisiana Native Guard

editOn September 27, 1862, Butler formed the first African-American regiment in the US Army, the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, and commissioned 30 officers to command it at the company level. This was highly unusual, as most USCT regiments were commanded by white officers only. "Better soldiers never shouldered a musket," Butler wrote, "I observed a very remarkable trait about them. They learned to handle arms and to march more easily than intelligent white men. My drillmaster could teach a regiment of Negroes that much of the art of war sooner than he could have taught the same number of students from Harvard or Yale." The regiment would serve Butler effectively during the Siege of Port Hudson.[75] Butler organized three regiments totaling 3,122 soldiers and officers.[76]

Army of the James

editButler's popularity with the Radicals meant that Lincoln could not readily deny him a new posting. Lincoln considered sending him to a position in the Mississippi River area in early 1863, and categorically refused to send him back to New Orleans.[77] In November 1863, he finally gave Butler command of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina based in Norfolk, Virginia. In January 1864, Butler played a pivotal role in the creation of six regiments of U.S. Volunteers recruited from among Confederate prisoners of war ("Galvanized Yankees") for duty on the western frontier.[78] In May, the forces under his command were designated the Army of the James. On November 4, 1864, Butler arrived in New York City with 3,500 troops of the Army of the James. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had "requested that Grant send troops to New York City to help oversee the election there. Stanton's concern arose from the city's perennial political and racial divisions, which had erupted during the 1863 draft riots,"[79][80] and because of fear of Confederates coming from Canada to burn the city on Election Day. Grant selected Butler for the assignment. "Even though he knew nothing about the plot [to burn the city] and did nothing to prevent it, Butler's mere presence with his 3,500 troops" demoralized the leaders of the conspiracy, who postponed it until November 25, when it failed.[81]

The Army of the James also included several regiments of United States Colored Troops. These troops saw combat in the Bermuda Hundred campaign (see below). At the Battle of Chaffin's Farm (sometimes also called the Battle of New Market Heights), the USCT troops performed extremely well. The 38th USCT defeated a more powerful force despite intense fire, heavy casualties, and terrain obstacles. Butler awarded the Medal of Honor to several men of the 38th USCT. He also ordered a special medal designed and struck, which was awarded to 200 African-American soldiers who had served with distinction in the engagement. This was later called the Butler Medal.

Bermuda Hundred campaign

editIn the spring of 1864, the Army of the James was directed to land at Bermuda Hundred on the James River, south of Richmond, and from there attack Petersburg. This would sever the rail links supplying Richmond, and force the Confederates to abandon the city. In spite of Grant's low opinion of Butler's military skills, he was given command of the operation.

Butler's force landed on May 5, when Petersburg was almost undefended, but Butler became unnerved by the presence of a handful of Confederate militia and home guards. While he dithered, the Confederates assembled a substantial force under General P. G. T. Beauregard. On 13 May, Butler's advance toward Richmond was repulsed. On May 16, the Confederates drove Butler's force back to Bermuda Hundred, bottling up the Union troops in a loop of the James River. Both sides entrenched; the Union troops were safe but impotent, and Beauregard sent most of his troops as reinforcements to Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Had Butler been more aggressive in early May, he might have taken Petersburg or even Richmond itself and ended the war a year early, although his two West Pointer corps commanders Maj. Gen "Baldly" Smith and Quincy Gilmore also did not perform well or make up for Butler's limitations as a general.

Despite this fiasco, Butler remained in command of the Army of the James.

Fort Fisher and final recall

editAlthough Grant had largely been successful in removing incompetent political generals from service, Butler could not be easily gotten rid of.[82] As a prominent Radical Republican, Butler was a potential replacement of Lincoln as presidential nominee.[83] Lincoln had even asked Butler to be the 1864 nominee for vice president,[82] as did Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, who sought to replace Lincoln as president.[84] In reply to Lincoln's offer, Butler said, "Tell him ... I would not quit the field [resign as major general] to be Vice-President, even with himself as President, unless he will give me bond with sureties ... that he will die or resign within three months after his inauguration. Ask him what he thinks I have done to deserve the punishment ... of being made to sit as presiding officer over the Senate, to listen for four years to debates more or less stupid, in which I can take no part or say a word...."[85]

There was no good place to put Butler; sending him to Missouri or Kentucky would likely end in disaster, so it was considered safer to leave him where he was in Virginia. More worrying was the fact that Butler was one of the highest ranking volunteer major generals in the Union army; next to Grant himself, he was the ranking field officer in the Eastern theater, and command of the Army of the Potomac would default to him in Grant's absence. For that reason, Grant remained with the army as much as possible and only made trips away from the front when it was absolutely necessary.

In December, troops from the Army of the James were sent to attack Fort Fisher in North Carolina with Butler in command. Butler devised a scheme to breach the defenses with a boat loaded with gunpowder, which failed completely. He then declared that Fort Fisher was impregnable and withdrew his troops without authorization. However, Admiral David Dixon Porter (commander of the naval element of the expedition) informed Grant that it could be taken easily if anyone competent were put in charge.

This mismanagement finally led to his recall by Grant in early 1865. As Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was not in Washington at the time,[82] Grant appealed directly to Lincoln for permission to terminate Butler, noting "there is a lack of confidence felt in [Butler's] military ability". Grant also voiced his suspicions about corruption going on in Butler's department, including smuggling of supplies to Lee's army, and that Butler arbitrarily arrested anyone who noticed what was going on, although, due to Butler's formidable political connections, nothing came of Grant's complaints.[86] By this point, the presidential election was over, so the administration no longer had to be concerned about Butler's running for president, and, in General Order Number 1, Lincoln relieved him from command of the Department of North Carolina and Virginia and ordered him to report to Lowell, Massachusetts.[82] Grant informed Butler of his recall on January 8, 1865, and named Major General Edward O. C. Ord to replace him as commander of the Army of the James.[82] "Embarrassed and outraged, Butler broke off all relations with Grant and set out to destroy him."[87] In 1867, when it seemed that Grant might run for president, Butler "employed detectives in an effort to prove that Grant was 'a drunkard, after fast horses, women and whores.' Grant, he announced, was 'a man without a head or a heart, indifferent to human suffering and impotent to govern.'"[87]

Rather than report to Lowell, Butler went to Washington, where he used his considerable political connections to get a hearing before the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War in mid-January. At his hearing Butler focused his defense on his actions at Fort Fisher. He produced charts and duplicates of reports by subordinates to prove he had been right to call off his attack of Fort Fisher, despite orders from General Grant to the contrary. Butler claimed the fort was impregnable. To his embarrassment, a follow-up expedition led by Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry and Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames (Butler's future son-in-law) captured the fort on January 15, and news of this victory arrived during the committee hearing; Butler's military career was over.[82] He was formally retained until November 1865 with the idea that he might act as military prosecutor of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.[88]

Colonization

editGeneral Butler claimed that Lincoln approached him in 1865, a few days before his assassination, to talk about reviving colonization in Panama.[89] Since the mid-twentieth century, historians have debated the validity of Butler's account, as Butler wrote it years after the fact and was prone to exaggerating his prowess as a general.[90] Recently discovered documents prove that Butler and Lincoln did indeed meet on April 11, 1865, though whether and to what extent they talked about colonization is not recorded except in Butler's account.[91]

Financial dealings

editNegative perceptions of Butler were compounded by his questionable financial dealings in several of his commands, as well as the activities of his brother Andrew, who acted as Butler's financial proxy and was given "almost free rein" to engage in exploitative business deals and other "questionable activities" in New Orleans.[21] Upon arriving in the city, Butler immediately began attempts to participate in the lucrative inter-belligerent trade. He used a Federal warship to send $60,000 in sugar to Boston where he expected to sell it for $160,000. However, his use of the government ship was reported to the military authorities, and Butler was chastised. Instead of earning a profit, military authorities permitted him to recover only his $60,000 plus expenses. Thereafter, his brother Andrew officially represented the family in such activities. Everyone in New Orleans believed that Andrew accumulated a profit of $1–$2 million while in Louisiana. Upon inquiry from Treasury Secretary Chase in October 1862, the general responded that his brother actually cleared less than $200,000 (~$4.76 million in 2023).[92] When Butler was replaced in New Orleans by Major General Nathaniel Banks, Andrew Butler unsuccessfully tried to bribe Banks with $100,000 if Banks would permit Andrew's "commercial program" to be carried out "as previous to [Banks's] arrival."[93]

Butler's administration of the Norfolk district was also tainted by financial scandal and cross-lines business dealings. Historian Ludwell Johnson concluded that during that period: "... there can be no doubt that a very extensive trade with the Confederacy was carried on in [Butler's Norfolk] Department.... This trade was extremely profitable for Northern merchants ... and was a significant help to the Confederacy.... It was conducted with Butler's help and a considerable part of it was in the hands of his relatives and supporters."[94]

Shortly after arriving in Norfolk, Butler became surrounded by such men. Foremost among them was Brigadier General George Shepley, who had been military governor of Louisiana. Butler invited Shepley to join him and "take care of Norfolk." After his arrival, Shepley was empowered to issue military permits allowing goods to be transported through the lines. He designated subordinate George Johnston to manage the task. In fall 1864, Johnston was charged with corruption. However, instead of being prosecuted, he was allowed to resign after saying he could show "that General Butler was a partner in all [the controversial] transactions," along with the general's brother-in-law Fisher Hildreth. Shortly thereafter, Johnston managed a thriving between-the-lines trade depot in eastern North Carolina. There is no doubt that Butler was aware of Shepley's trading activities. His own chief of staff complained about them and spoke of businessmen who "owned" Shepley. Butler took no action.[95]

Much of the Butler-managed Norfolk trade was via the Dismal Swamp Canal to six northeastern counties in North Carolina separated from the rest of the state by Albemarle Sound and the Chowan River. Although cotton was not a major crop, area farmers purchased bales from the Confederate government and took them through the lines where they would be traded for "family supplies." Generally, the Southerners returned with salt, sugar, cash, and miscellaneous supplies. They used the salt to preserve butchered pork, which they sold to the Confederate commissary. After Atlantic-blockaded ports such as Charleston and Wilmington were captured, this route supplied about ten thousand pounds of bacon, sugar, coffee, and codfish daily to Lee's army. Ironically, Grant was trying to cut off Lee's supplies from the Confederacy when Lee's provender was almost entirely furnished from Yankee sources through Butler-controlled Norfolk.[96] Grant wrote of the issue, "Whilst the army was holding Lee in Richmond and Petersburg, I found ... [Lee] ... was receiving supplies, either through the inefficiency or permission of [an] officer selected by General Butler ... from Norfolk through the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal."[97]

Butler's replacement, Major General George H. Gordon, was appalled at the nature of the ongoing trade. Reports were circulating that $100,000 in goods daily left Norfolk for Rebel armies. Grant instructed Gordon to investigate the prior trading practices at Norfolk, after which Gordon released a sixty-page indictment of Butler and his cohorts. It concluded that Butler associates, such as Hildreth and Shepley, were responsible for supplies from Butler's district pouring "directly into the departments of the Rebel Commissary and Quartermaster." Some Butler associates sold permits for cross-line trafficking for a fee.[98] Gordon's report received little publicity, because of the end of the war and Lincoln's assassination.[99]

Postbellum business and charitable dealings

editButler greatly expanded his business interests during and after the Civil War, and was extremely wealthy when he died, with an estimated net worth of $7 million ($240 million today). Historian Chester Hearn believed "The source of his fortune has remained a mystery, but much of it came from New Orleans...."[100] However, Butler's mills in Lowell, which produced woolen goods and were not hampered by cotton shortages, were economically successful during the war, supplying clothing and blankets to the Union Army, and regularly paying high dividends.[101] Successful postwar investments included a granite company on Cape Ann and a barge freight operation on the Merrimack River. After learning that no domestic manufacturer produced bunting, he invested in another Lowell mill to produce it, and convinced the federal government to enact legislation requiring domestic sources for material used on government buildings. Less successful ventures included investments in real estate in Virginia, Colorado, and the Baja Peninsula of western Mexico, and a fraudulent gold mining operation in North Carolina.[102] He also founded the Wamesit Power Company and the United States Cartridge Company,[103] and was one of several high-profile investors who were deceived by Philip Arnold in the famous Diamond hoax of 1872.

Butler put some of his money into more charitable enterprises. He purchased confiscated farms in the Norfolk, Virginia area during the war and turned them over to cooperative ventures managed by local African Americans, and sponsored a scholarship for African-Americans at Phillips Andover Academy.[104] He also served for fifteen years in executive positions of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, including as its president from 1866 through 1879.[105]

His law firm also expanded significantly after the war, adding offices in New York City and Washington. High-profile cases he took included the representation of Admiral David Farragut in his quest to be paid by the government for prizes taken by the Navy during the war, and the defense of former Secretary of War Simon Cameron against an attempted extortion in a salacious case that gained much public notice.[106]

Butler built a mansion immediately across the street from the United States Capitol in 1873–1874, known as the Butler Building.[107][108][109] One unit of the building was constructed to be fireproof so that it could be rented as storage for valuable and irreplaceable survey records, maps, and engraving plates of the United States Coast Survey (renamed the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1878), whose headquarters in the Richards Building was directly next door.[109][110] The building was used by President Chester A. Arthur while the White House was being refurnished.[108][111] On April 10, 1891, the Department of the Treasury purchased the building from Butler for $275,000, (~$8.43 million in 2023) and it became the headquarters of the U.S. Marine Hospital Service, with its Hygienic Laboratory (the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health) occupying its top floor.[109][112]

Early postbellum political activities

editAt the urging of his wife, Butler actively sought another political position in the Lincoln administration, but this effort came to an end with Lincoln's assassination in April 1865.[113] Soon after he became president, however, Andrew Johnson sought Butler's legal advice as to whether he could prosecute Robert E. Lee for treason, even though General Grant had granted Lee parole at Appomattox. "On April 25, 1865, Butler wrote a lengthy memorandum to Johnson explaining why the parole Lee received from Grant did not protect him from being prosecuted for treason.... Butler argued that parole was merely a military arrangement that allowed a prisoner 'the privilege of partial liberty instead of close confinement.... Indeed the Lieutenant General [Grant] had not authority to grant amnesty or pardon even if he had undertaken to do so.'"[114]

In March 1866, Butler argued in the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of the United States in Ex parte Milligan, in which the Court held, against the United States, that military commission trials could not replace civilian trials when courts were open and where there was no war.[115]

United States House of Representatives (1867–75 and 1877–79)

editPopular from his reputation as a general,[116] Butler turned his eyes to Congress and was elected in 1866 on a platform of civil rights and opposition to President Andrew Johnson's weak Reconstruction policies. He supported a variety of populist and social reform positions, including women's suffrage, an eight-hour workday for federal employees, and the issuance of greenback currency.[117] In his stump speeches, Butler not only denounced Johnson, but also regularly called for his removal from office.[116]

Butler served four terms (1867–75) before failing to be reelected (after hostile Republicans led by Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar succeeded in denying him renomination for his congressional seat in 1874).[118] He was then elected in 1876 and served a single additional term. As a former Democrat, he was initially opposed by the state Republican establishment, which was particularly unhappy with his support of women's suffrage and greenbacks. The more conservative party organization closed ranks against him to reject his two attempts (in 1871 and 1873) to gain the Republican nomination for Governor of Massachusetts.[119]

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

editButler was an early and fierce supporter of impeaching President Johnson.

As a congressional candidate, by October 1866 Butler was traveling to multiple cities across the United States delivering speeches in which he promoted the prospect of impeaching Johnson.[120][121] He detailed six specific charges that Johnson should be impeached for.[120] These were:

- Seeking to overthrow the government of the United States, doing so by attempting to bring Congress "to disgrace" by refusing to execute or carry out the laws that it had passed which he disagreed with, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Freedmen's Bureau bills[120]

- Corruptly using his powers to appoint and remove officers[120]

- Declaring peace in the American Civil War without the consent of Congress[120]

- Corruptly using his pardon powers and restoring to former Confederates property seized by the United States in the Civil War[120]

- Failing to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1866[120]

- Complicity in the New Orleans massacre of 1866[120]

By the end of November 1866, Congressman-elect Butler was promoting the idea of impeaching Johnson on the basis of eight articles.[122] The articles that he proposed charged Johnson with:

- "Degrading and debasing...the station and dignity of the office of Vice-President and that of vice president" by being publicly drunk at "official and public occasions"[122]

- "Officially and publicly making declarations and inflammatory harangues, indecent and unbecoming in derogation of his high office, dangerous to the permanency of our republican form of government, and in design to excite the ridicule, fear, hatred, and contempt of the people against the legislative and judicial departments therof"[122]

- "Wickedly, tyrannically, and unconstitutionally...usurping the lawful rights and powers of the Congress"[122]

- "Wickedly and corruptly using and abusing" the constitutional power of the President by making recess appointments with the "design to undermine, overthrow and evade the power" of the Congress to advice and consent on such appointments[122]

- "Improperly, wickedly, and corruptly abusing the constitutional power of pardons" with his pardons for ex-Confederates; "knowingly and willfully violating the constitutionally enacted laws of the United States by appointing disloyal men to office and illegally and without right giving to them emoluments of such office from the Treasury, well knowing the appointees to be ineligible to office"[122]

- "Knowingly and willfully neglecting and refusing to carry out the constitutional laws of Congress" in the former Confederate states "in order to encourage men lately into rebellion and in arms against the United States to the oppression and injury of the loyal true citizens of such States"[122]

- "Unlawfully, corruptly, and wickedly confederating and conspiring with one John T. Monroe...and other evil disposed persons, traitors, and Rebels" in the New Orleans massacre of 1866.[122]

In March 1867, Butler unsuccessfully lobbied to be appointed to the House Committee on the Judiciary, which was overseeing the first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson. John Bingham, who had worked to combat many of the early efforts to impeach Johnson,[123] strongly opposed the prospect of Butler's being appointed to that committee.[124]

Although Butler was not included on the select committee appointed to draft the articles of impeachment for Johnson after he was impeached in February 1868, he independently wrote his own article of impeachment. He did so at the urging of Thaddeus Stevens, a member of the select committee who felt that Radical Republicans on the select committee were conceding too much to moderates in limiting the scope of the violations of law that the articles of impeachment the committee was drafting would charge Johnson with.[125] The article Butler wrote cited no clear violation of law, but instead charged Johnson with attempting, "to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach the Congress of the United States."[125] The article was seen as having been written in response to speeches that Johnson had made during his "Swing Around the Circle".[126] Butler's article was initially rejected by a 48–74 vote on March 2, 1868. However, it was subsequently adopted as the tenth article of impeachment by a 88–45 vote after it was reintroduced by the impeachment managers the following day.[125][127][128] It was the only article of impeachment that any Republican congressman voted against.[129][128][130][131]

Seated L-R: Butler, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams, John Bingham;

Standing L-R: James F. Wilson, George S. Boutwell, John A. Logan

Butler was elected by the House serve as be one of the managers (prosecutors) for the impeachment trial of Johnson before the Senate.[132][133][127] Although Thaddeus Stevens was the principal guiding force behind the impeachment effort, he was aging and ill at the time, and Butler stepped in to become the main organizing force in the prosecution. The case was focused primarily on Johnson's removal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, and was weak because the constitutionality of the law had not been decided. The trial was a somewhat uncomfortable affair, in part because the weather was hot and humid, and the chamber was packed. The prosecution's case was a humdrum recitation of facts already widely known, and it was attacked by the defense's William Evarts, who drowned the proceedings by repeatedly objecting to Butler's questions, often necessitating a vote by the Senate on whether to allow the question. Johnson's defense focused on the point that his removal of Stanton fell within the bounds of the Tenure of Office Act. Despite some missteps by the defense and Butler's vigorous cross-examination of defense witnesses, the impeachment failed by a single vote. In the interval between the trial and the Senate vote, Butler searched without success for substantive evidence that Johnson operatives were working to bribe undecided Senators.[134] After acquittal on May 16, 1868, of the first article voted on,[135] Senate Republicans voted to adjourn for ten days, seeking time to possibly change the outcome on the remaining articles.[136]

Later on May 16, 1868, The House enabled an investigation by the impeachment managers into alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate". Butler led this investigation, approving summons for several eyewitnesses the same day that the investigation was authorized.[137] Butler looked into the possibility that four of the seven Republican senators who voted for acquittal had been improperly influenced in their votes. He uncovered some evidence that promises of patronage had been made and that money may have changed hands but was unable to decisively link these actions to any specific senator.[138]

On May 26, 1868, Johnson was acquitted on the second and third articles voted on, and the trial was adjourned. On August 3, 1868, Johnson wrote that Butler was "the most daring and unscrupulous demagogue I have ever known."[136] Butler's performance as a prosecutor has been regarded as subpar, and this has been cited as a factor that contributed to Johnson's acquittal.[139] After the trial resulted in an acquittal, Butler continued the impeachment managers' investigation into possible corrupt influence on the trial, conducting hearings on reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal.[140] He published the final report of the investigation on July 3, 1868, having failed to prove the alleged corruption that had been investigated.[141]

Civil Rights Act of 1871

editButler wrote the initial version of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act). After his bill was defeated, Representative Samuel Shellabarger of Ohio drafted another bill, only slightly less sweeping than Butler's, that successfully passed both houses and became law upon Grant's signature on April 20.[133][142] Along with Republican senator Charles Sumner, Butler proposed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, a seminal and far-reaching law banning racial discrimination in public accommodations.[143] The Supreme Court of the United States declared the law unconstitutional in the 1883 Civil Rights Cases.[144]

Relationship with President Ulysses S. Grant

editButler managed to rehabilitate his relationship with Ulysses Grant after the latter became president, to the point where he was seen as generally speaking for the president in the House. He annoyed Massachusetts old-guard Republicans by convincing Grant to nominate one of his protégés to be collector of the Port of Boston, an important patronage position, and secured an exception for an ally, John B. Sanborn, in legislation regulating the use of contractors by the Internal Revenue Service for the collection of tax debts. In 1874, Sanborn would be involved in the Sanborn Contract scandal, in which he was paid over $200,000 (~$4.86 million in 2023) for collecting debts that would likely have been paid without his intervention.[145]

Other actions

editIn 1871, Butler sponsored an appearance by suffragette Victoria Woodhull before a congressional committee. In her testimony, Woodhull argued that the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution of the United States implicitly grant women the right to vote. During his tenure in Congress, Butler served for some time as the chairman of the House Committee on the Judiciary.[146] During the 41st Congress, Butler served as the chairman of the House Select Committee on Reconstruction.[147]

Governor of Massachusetts (1883–84)

editUnsuccessful bids

editButler made four unsuccessful attempts at being elected governor of Massachusetts between the years 1871 and 1879.

In 1871 and 1874, he attempted to receive the Republican nomination, but the more conservative party organization closed ranks against him to deny him the nomination.[119]

Butler again ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1878, this time as an independent with Greenback Party support. He had unsuccessfully also sought the Democratic nomination. He was denied the Democratic nomination by the party's leadership, which refused to admit him into the party. Despite this, Butler did receive the nomination of a populist rump group of Democrats that disrupted the main convention, forcing it to adjourn to another location.[148] He was renominated by the populist Democrats in similar fashion in 1879. In both years, Republicans won against the divided Democrats.[149]

Because Butler sought the governorship in part as a stepping stone to the presidency, he opted not to run for it again until 1882.[149]

Term in office

editIn 1882, Butler successfully litigated Juilliard v. Greenman before the Supreme Court. In what was seen as a victory for Greenback supporters, the case confirmed that the government had the right to issue paper currency for public and private debts.[150]

In 1882, Butler again ran for governor of Massachusetts, this time being elected by a 14,000 margin after winning nomination by both Greenbacks and an undivided Democratic party.[151] As governor, Butler was active in promoting reform and competence in administration, in spite of a hostile Republican legislature and Governor's Council.[152] He appointed the state's first Irish-American judge, its first African-American judge, George Lewis Ruffin,[119] and appointed the first woman to executive office, Clara Barton, to head the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women. He also graphically exposed the mismanagement of the state's Tewksbury Almshouse under a succession of Republican governors.[153] Butler was somewhat notoriously snubbed by Harvard University, which traditionally granted honorary degrees to the state's governors. Butler's honorarium was denied because the Board of Overseers, headed by Ebenezer Hoar, voted against it.[154]

Butler's bid for reelection in 1883 was one of the most contentious campaigns of his career. His presidential ambitions were well known, and the state's Republican establishment, led by Ebenezer and George Frisbie Hoar, poured money into the campaign against him. Running against Congressman George D. Robinson (whose campaign manager was a young Henry Cabot Lodge), Butler was defeated by 10,000 votes, out of more than 300,000 cast.[153] Butler is credited with beginning the tradition of the "lone walk", the ceremonial exit from the office of Governor of Massachusetts, after finishing his term in 1884.[155]

1884 presidential campaign

editButler parlayed his victory in the Juilliard v. Greenman decision into a run for president in 1884. Butler was nominated by the Greenback and Anti-Monopoly parties,[156] but was unsuccessful in getting the Democratic nomination, which went to Grover Cleveland.[157] Cleveland refused to adopt parts of Butler's platform in exchange for his political support, prompting Butler to run in the general election rather than withdrawing in deference to Cleveland.[158] He sought to gain electoral votes by engaging in fusion efforts with Democrats in some states and Republicans in others,[159] in which he took what were perceived in the contemporary press as bribes $25,000 from the campaign of Republican James G. Blaine.[160] The effort was in vain: Butler polled 175,000 out of 10 million votes cast in the election, which Cleveland won.[161]

Later years and death

editIn his later years Butler reduced his activity level, working on his memoir, Butler's Book, which was published in 1892.[162] Butler's Book has 1,037 pages plus a 94-page appendix consisting of letters. In it, "Butler focused by far the majority of his attention on the war years, vigorously defending his often-maligned record." He arranged "with his longtime friend and ally James Parton [author of General Butler in New Orleans] that Parton would finish the book if Butler died before it was done. (As it happens, Parton died first, in October 1891)."[163] Butler's biographer Richard S. West, Jr. writes, "The autobiography may be said to be generally true without being meticulously accurate".[164]

Butler died on January 11, 1893, of complications from a bronchial infection, two days after arguing a case before the Supreme Court.[165] He is buried in his wife's family cemetery, behind the main Hildreth Cemetery in Lowell.[166] The inscription on Butler's monument reads, "the true touchstone of civil liberty is not that all men are equal but that every man has the right to be the equal of every other man—if he can."[167]

His daughter Blanche married Adelbert Ames, a Mississippi governor and senator who had served as a general in the Union Army during the war. Butler's descendants include the scientist Adelbert Ames Jr., suffragist and artist Blanche Ames Ames, Butler Ames, Hope Butler, and George Plimpton.

Legacy

editAccording to biographer Hans L. Trefousse:

- Butler was one of the most controversial 19th-century American politicians. Demagogue, speculator, military bungler, and sharp legal practitioner--he was all of these; and he also was a fearless advocate of justice for the downtrodden, a resourceful military administrator, and an astonishing innovator. He was passionately hated and equally strongly admired, and if the South called him "Beast," his constituents in Massachusetts were fascinated by him.... As a leading advocate of radical Reconstruction, Butler played an important role in the conflict between president and Congress. His effectiveness was marred by the frequency with which engaged in personal altercations, and his conduct as one of the principal managers of the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson was dubious. Nevertheless he deserves recognition as a persistent critic of southern terrorism and is one of the chief authors of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.[168]

Black newspapers eulogized him "consistently as a 'friend of the colored race,' 'a staunch and enthusiastic advocate' of Black progress, and 'one of the few American statesmen who have stood as a wall of defense in favor of equal rights for all American citizens.' ...[169] The New England Torchlight put it simply: 'The white South hated him. The black South loved him.'"[170]

Ideology ("Butlerism")

editButlerism | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Benjamin Butler |

| Ideology | • Radical Republicanism • Irish nationalism • Women's suffrage • Monetary inflation • Pro-spoils system |

| Political position | Populist |

| National affiliation |

|

Butlerism was a political term in the United States during the Gilded Age applied as a pejorative by its opponents[171][172] that referred to the political causes of Butler. A populist movement, it was criticized for its "spirit of the European mob," and appealed to support for women's suffrage, Irish nationalism, an eight-hour work day, monetary inflation, and the usage of greenbacks to pay off the national debt.[173]

The ideology and political themes of Butlerism, which opposed civil service reform, advocated inflationary monetary policy, and assailed capitalism as exploiting workmen, clashed with the aims of liberal reformers in the Gilded Age.[173] Its left-wing stances on monetary policy came at odds with the considerably more conservative members of the Republican Party, including Ulysses S. Grant and James G. Blaine. When Butler and Democratic congressman George H. Pendleton led a bipartisan wing of inflationists advocating the continued usage of greenbacks, Blaine emerged as the first member of Congress antagonizing the repudiation theory.[174] After President Grant in 1874 vetoed Butler's "inflation bill,"[175] Harper's Weekly published a cartoon by Thomas Nast depicting Grant, a supporter of sound money, as having "bottled up" Butlerism.[176]

In spite of Butlerism's radical elements during its time, Butler during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes was closely aligned with the politics of the conservative Stalwart faction in his support for Ulysses S. Grant, due to their shared concern for civil rights, tendency to "wave the bloody shirt," and antipathy towards the hardline civil service reform efforts.[177] These aims were in turn harshly lamented by reformers, including Charles Francis Adams Jr., and Carl Schurz.

Opponents of Butler derided the ideology as involving "no principle which is elevating, it inspires no sentiment which is ennobling."[171] In turn, defenders of Butlerism retorted:

There is one thing that this unholy alliance cannot efface, that General Butler has pluck and brains, and they will find that the more people believe in men of that make-up. The country today needs more "Butlerism" and less "toadyism."

Attacks on Butlerism included one by Kentucky Democrat John Y. Brown in February 1874, who complained: "If I wished to describe all that was pusillanimous in war, inhuman in peace, forbidden in morals, and infamous in politics, I should call it 'Butlerism.'"[172] Brown subsequently faced a censure for his remarks, and bickering on the House floor soon followed.

Electoral history

editGubernatorial

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Nathaniel Prentiss Banks (incumbent) | 58,804 | 54.02 | |

| Democratic | Benjamin Franklin Butler | 35,326 | 32.45 | |

| Know Nothing | George Nixon Briggs | 14,365 | 13.20 | |

| Total votes | 108,140 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | John Albion Andrew | 104,527 | 61.63 | |

| Democratic | Erasmus Beach | 35,191 | 20.75 | |

| Constitutional Union | Amos Adams Lawrence | 23,816 | 14.04 | |

| Southern Democratic | Benjamin Franklin Butler | 6,000 | 3.54 | |

| Total votes | 169,534 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William B. Washburn (incumbent) | 563 | 67.10 | |

| Republican | Benjamin Butler | 259 | 30.87 | |

| Republican | Scattering | 17 | 2.03 | |

| Total votes | 839 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Thomas Talbot | 134,725 | 52.56 | |

| Democratic | Benjamin Butler | |||

| Greenback | Benjamin Butler | |||

| Total | Benjamin Butler | 109,435 | 42.69 | |

| Ind. Democrat | Josiah Gardner Abbott | 10,162 | 3.96 | |

| Prohibition | Alonzo Ames Miner | 1,913 | 0.75 | |

| Write-in | 97 | 0.04 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | John Davis Long | 122,751 | 50.38 | |

| Democratic | Benjamin Butler | 109,149 | 44.80 | |

| Independent Democrat | John Quincy Adams II | 9,989 | 4.10 | |

| Prohibition | D.C. Eddy | 1,645 | 0.68 | |

| Others | Others | 108 | 0.04 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Benjamin Franklin Butler | 133,946 | 52.27 | |

| Republican | Robert R. Bishop | 119,997 | 46.82 | |

| Prohibition | Charles Almy | 2,137 | 0.83 | |

| Others | Others | 198 | 0.08 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | George D. Robinson | 160,092 | 51.25 | |

| Democratic | Benjamin Franklin Butler (incumbent) | 150,228 | 48.10 | |

| Prohibition | Charles Almy | 1,881 | 0.60 | |

| Others | Others | 156 | 0.05 | |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Jordan, Brian Matthew, "Benjamin F. Butler, Ex Parte Milligan, and the Unending Civil War," p. 35.

- ^ a b West (1965), pp. 8–9

- ^ LAW REPORTS.; The Will of Col. A. J. Butler. Surrogate's Court--May 31..., New York Times, 1 June 1864

- ^ West (1965), p. 10

- ^ West (1965), pp. 10–13

- ^ West (1965), pp. 13–16

- ^ a b West (1965), pp. 17–23

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 13

- ^ West (1965), pp. 25, 27

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ West (1965), p. 27

- ^ Ward, Jean M. (2022). "George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)". Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Hearn (2000), p. 19

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 14

- ^ a b Quarstein (2011), p. 29

- ^ West (1965), pp. 32–35

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 18

- ^ Dupree (2008), p. 11

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 20

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 21

- ^ a b c d e Jones, Terry L. (May 18, 2012). "The Beast in the Big Easy". The New York Times. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ West (1965), p. 20

- ^ West (1965), pp. 41–42

- ^ Wells (2011), p. 40

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 23

- ^ a b Hearn (2000), p. 24

- ^ Hearn (2000), p. 25

- ^ Quarstein (2011), p. 31

- ^ a b c Wells (2011), p. 34

- ^ West (1965), pp. 51–53

- ^ West (1965), p. 54

- ^ West (1965), p. 57

- ^ West (1965), pp. 58–60

- ^ Neilson, Larz F., "History: Butler saved Maryland for the Union, Wilmington Town Crier, February 24, 2019

- ^ West (1965), p. 61

- ^ West (1965), pp. 65–70

- ^ West (1965), pp. 65, 70–73

- ^ West (1965), p. 76

- ^ West (1965), pp. 72–74

- ^ Lossing and Barritt, pp. 500–502

- ^ Quarstein (2011), p. 38

- ^ Quarstein (2011), p. 62

- ^ Quarstein and Mroczkowski (2000), p. 48

- ^ Lossing and Barritt, p. 505

- ^ Poland, pp. 232–233

- ^ Quarstein and Mroczkowski (2000), p. 49

- ^ West (1965), pp. 102–103

- ^ West (1965), pp. 103–105

- ^ West (1965), p. 107

- ^ West (1965), pp. 110–115

- ^ West (1965), p. 113

- ^ Butler, Benjamin, Butler's Book, p. 257

- ^ Quarstein (2011), p. 53

- ^ Oakes (2013), pp. 95-100

- ^ Stahr, Walter, Samuel Chase: Lincoln's Vital Rival. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021, p. 342

- ^ Finkelman (2006), p. 277

- ^ Oakes (2013), pp. 100-101

- ^ Mississippi History Now: Union Soldiers on Ship Island During the Civil War Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shapell

- ^ Holzman, "Ben Butler in the Civil War", pp. 330–345

- ^ "Broadside depicting Benjamin Butler's General Order No. 28 | the Historic New Orleans Collection".

- ^ "Union Leader Ben Butler Seeks Support in a Hostile New Orleans". April 27, 2012.

- ^ West, Jr., Richard S., Lincoln's Scapegoat General, p. 141.

- ^ West, Jr., Richard S., Lincoln's Scapegoat General, p. 143.

- ^ Orcutt

- ^ Hearn (1997), pp. 185–187

- ^ Butler, 1892, p. 439

- ^ Butler, 1892, p. 442

- ^ In Butler's Book, p. 440, Butler wrote, "I thought I should be in the utmost danger if I did not have him executed, for the question was now to be determined whether I commanded that city or whether the mob commanded it".

- ^ Jefferson Davis' Proclamation

- ^ Trefousse (1969), p. 242

- ^ Trefousse (1969), p. 281

- ^ Trefousse (1969), pp. 281–282

- ^ "Why do people here hate Union Gen. Benjamin Butler?". Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "The Color of Bravery". American Battlefield Trust. July 29, 2013.

- ^ Westwood, Howard C. "Benjamin Butler's Enlistment of Black Troops in New Orleans in 1862" Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 26, no. 1 (Winter 1985), pp. 5–22 ("3,122" on p. 18).

- ^ Trefousse (1969), pp. 242–244

- ^ Brown (1985), pp. 65–67

- ^ Elizabeth D. Leonard, Benjamin Franklin Butler: A Noisy, Fearless Life, p. 149

- ^ Robert S. Holzman, Stormy Ben Butler (1954), pp. 142–143.

- ^ Clint Johnson, A Vast and Fiendish Plot: The Confederate Attack on New York City. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. (2010), pp. 180–181, 185.

- ^ a b c d e f Foote, pp. 739–740

- ^ Trefousse (1969), pp. 294–295

- ^ West, Jr., Richard S., Lincoln's Scapegoat General, pp. 230-231.

- ^ West, Jr., Richard S., Lincoln's Scapegoat General, p. 231.

- ^ West (1965), p. 291

- ^ a b Simpson, Brooks D., Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868, Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991, p. 210.

- ^ West (1965), pp. 312–313

- ^ Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major General Benj. F. Butler: Butler's Book (Boston: A. M. Thayer, 1892), p. 903

- ^ Mark E. Neely, "Abraham Lincoln and Black Colonization: Benjamin Butler's Spurious Testimony," Civil War History 25 (1979), pp. 77–83

- ^ Magness, Phillip W. (Winter 2008). "Benjamin Butler's Colonization Testimony Reevaluated". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 29 (1). hdl:2027/spo.2629860.0029.103. ISSN 1945-7987.

- ^ Hearn (1997), pp. 194, 195

- ^ Ludwell Johnson, "Red River Campaign: Politics and Cotton in the Civil War" (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1993) p. 52

- ^ Johnson, Ludwell, "Contraband Trade During the Last Year of the Civil War", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 91 No. 4 (March 1963), p. 646

- ^ Ludwell Johnson, "Contraband Trade During the Last Year of the Civil War" pp. 643–645

- ^ Philip Leigh, Trading With the Enemy: The Covert Economy During the American Civil War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2014) p. 99

- ^ The Record of Benjamin Butler From Original Sources (Boston: Pamphlet, 1883) p. 13

- ^ Frederick A. Wallace Civil War Hero George H. Gordon (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011) p.101; Robert Futrell "Federal Trade With the Confederate States" PhD dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 1950 p. 441

- ^ Philip Leigh, Trading With the Enemy: The Covert Economy During the American Civil War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2014) p. 100

- ^ Hearn (1997), p. 240

- ^ West (1965), p. 309

- ^ West (1969), pp. 310–311

- ^ "U.S. Cartridge Company" (PDF). Lowell Land Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ West (1965), pp. 309-310

- ^ West (1965), pp. 316 and 408-413

- ^ West (1965), pp. 313–316

- ^ Annual Report of the Superintendent, United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. Govt. print. off. 1916. p. 15.

- ^ a b Furman, Bess (1973). A Profile of the United States Public Health Service, 1798–1948. National Institutes of Health. pp. 198, 201–202, 367.

- ^ a b c Annual Report of the Superintendent, United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1919. pp. 17, 19.

- ^ Congressional Record, Forty-Third Congress, Third Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1875. p. 1814.

- ^ "Lost Capitol Hill: Another President on the Hill". The Hill is Home. June 4, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Harden, Victoria A.; Lyons, Michele (February 27, 2018). "NIH's Early Homes". NIH Intramural Research Program. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ West (1965), p. 320

- ^ Reeves, John, The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee: The Forgotten Case against an American Icon, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield (2018), pp. 60-61

- ^ Jordan, Brian Matthew. "Benjamin F. Butler, Ex Parte Milligan, and the Unending Civil War."

- ^ a b "Building the Case for Impeachment, December 1866 to June 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ West (1965), pp. 321–325

- ^ West (1965), pp. 350–351

- ^ a b c Trefousse (1999), p. 93

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Impeachment". Newspapers.com. Perrysburg Journal. October 26, 1866. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "Impeachment". Newspapers.com. Chicago Tribune. October 21, 1866. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Proposed Impeachment". Newspapers.com. The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia). December 1, 1866. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (1998). "From Our Archives: A New Look at the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. 113 (3): 493–511. doi:10.2307/2658078. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2658078. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Wineapple, Brenda (2019). "Twelve: Tenure of Office". The impeachers : The Trial of Andrew Johnson and The Dream of a Just Nation (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780812998368.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment - Butler's Additional Article- The Rules in the Senate". Newspapers.com. Chicago Evening Post at Newspapers.com. March 2, 1868. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Hinds, Asher C. (March 4, 1907). HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE (PDF). United States Congress. pp. 858 and 860. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "Journal of the United States House of Representatives (40th Congress, Second Session) pages 465 and 466". voteview.com. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ "40th Congress (1867-1869) > Representatives". voteview.com. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Journal of the United States House of Representatives (40th Congress, Second Session) pages 463 and 464". voteview.com. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ "Journal of the House of Representatives, March 2, 1868" (PDF). www.cop.senate.gov. United States Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Stewart, p. 159

- ^ a b Schlup and Ryan, p. 73

- ^ Stewart, pp. 181–218

- ^ Stewart, pp. 273–278

- ^ a b Truman, Benjamin C., "Anecdotes of Andrew Johnson," The Century Magazine, vol. 85, pp. 435–440, quotation on p. 440 (November 1912).

- ^ Stewart, p. 291

- ^ Stewart, pp. 280–294

- ^ "Benjamin Butler". www.impeach-andrewjohnson.com. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "Impeachment Skullduggery". Alexandria Gazette. May 26, 1868.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 303–304

- ^ Trelease, pp. 387ff

- ^ Rucker and Alexander, pp. 669-700

- ^ "Rolling Back Civil Rights". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Bunting, pp. 133-135

- ^ Glass, Andrew (July 29, 2013). "Former Gen. Benjamin Butler retires from Congress, July 29, 1878". Politico. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. House of Representatives. Select Committee on Reconstruction. 7/3/1867-3/2/1871 Organization Authority Record". catalog.archives.gov. National Archives Catelog. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ West (1965), pp. 365-368

- ^ a b West (1965), p. 369

- ^ West (1965), p. 380

- ^ West (1965), p. 372

- ^ West (1965), pp. 374-375

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 597

- ^ West (1965), pp. 376–377

- ^ "A Tour of the Grounds of the Massachusetts State House". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ West (1965), p. 383

- ^ West (1965), p. 388

- ^ West (1965), pp. 389-390

- ^ West (1965), pp. 400-404

- ^ West (1965), pp. 403-407

- ^ West (1965), p. 407

- ^ West (1965), pp. 408-413

- ^ Leonard, Elizabeth D., Benjamin Franklin Butler: A Noisy, Fearless Life, p. 270.

- ^ Lincoln's Scapegoat General, p. 418.