Berkeley (/ˈbɜːrkli/ BURK-lee) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Anglo-Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emeryville to the south and the city of Albany and the unincorporated community of Kensington to the north. Its eastern border with Contra Costa County generally follows the ridge of the Berkeley Hills. The 2020 census recorded a population of 124,321.

Berkeley | |

|---|---|

Looking west over the city from the Berkeley Hills, with San Francisco in the background | |

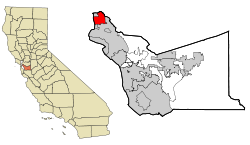

Location of Berkeley in Alameda County, California | |

| Coordinates: 37°52′18″N 122°16′22″W / 37.87167°N 122.27278°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Alameda |

| Incorporated | April 4, 1878[1] |

| Chartered | March 5, 1895[2] |

| Named for | George Berkeley |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager[2] |

| • Mayor | Jesse Arreguín[3] |

| • Council members by district number[3] |

|

| • State senator | Nancy Skinner (D)[6] |

| • Assembly member | Buffy Wicks (D)[7] |

| • U.S. rep. | Barbara Lee (D)[8] |

| Area | |

• Total | 17.66 sq mi (45.73 km2) |

| • Land | 10.43 sq mi (27.02 km2) |

| • Water | 7.22 sq mi (18.71 km2) 40.83% |

| Elevation | 171 ft (52 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 124,321 |

| • Rank | |

| • Density | 11,917.27/sq mi (4,601.36/km2) |

| Demonym | Berkeleyan |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes[11] | 94701–94710, 94712, 94720 |

| Area code | 510, 341 |

| FIPS code | 06-06000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1658037, 2409837 |

| Website | berkeleyca |

Berkeley is home to the oldest campus in the University of California, the University of California, Berkeley, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which is managed and operated by the university. It also has the Graduate Theological Union, one of the largest religious studies institutions in the world. Berkeley is considered one of the most socially progressive cities in the United States.

History

editIndigenous history

editThe site of today's City of Berkeley was the territory of the Chochenyo/Huchiun Ohlone people when the first Europeans arrived.[12] Evidence of their existence in the area include pits in rock formations, which they used to grind acorns, and a shellmound, now mostly leveled and covered up, along the shoreline of San Francisco Bay at the mouth of Strawberry Creek. Human remains and skeletons from Native American burials have been unearthed in West Berkeley and on campus alongside Strawberry Creek.[13][14] Other artifacts were discovered in the 1950s in the downtown area during remodeling of a commercial building, near the upper course of the creek.

Spanish and Mexican eras

editThe first people of European descent (most of whom were of mixed race and born in America[15]) arrived with the De Anza Expedition in 1776.[16] The De Anza Expedition led to establishment of the Spanish Presidio of San Francisco at the entrance to San Francisco Bay (the "Golden Gate)." Luis Peralta was among the soldiers at the Presidio. For his services to the King of Spain, he was granted a vast stretch of land on the east shore of San Francisco Bay (the contra costa, "opposite shore") for a ranch, including that portion that now comprises the City of Berkeley.

Luis Peralta named his holding "Rancho San Antonio." The primary activity of the ranch was raising cattle for meat and hides, but hunting and farming were also pursued. Eventually, Peralta gave portions of the ranch to each of his four sons. What is now Berkeley lies mostly in the portion that went to Peralta's son Domingo, with a little in the portion that went to another son, Vicente. No artifact survives of the Domingo or Vicente ranches, but their names survive in Berkeley street names (Vicente, Domingo, and Peralta). However, legal title to all land in the City of Berkeley remains based on the original Peralta land grant.

The Peraltas' Rancho San Antonio continued after Alta California passed from Spanish to Mexican sovereignty after the Mexican War of Independence. However, the advent of U.S. sovereignty after the Mexican–American War, and especially, the Gold Rush, saw the Peraltas' lands quickly encroached on by squatters and diminished by dubious legal proceedings. The lands of the brothers Domingo and Vicente were quickly reduced to reservations close to their respective ranch homes. The rest of the land was surveyed and parceled out to various American claimants (See Kellersberger's Map).

Politically, the area that became Berkeley was initially part of a vast Contra Costa County. On March 25, 1853, Alameda County was created from a division of Contra Costa County, as well as from a small portion of Santa Clara County. The area that became Berkeley was then the northern part of the "Oakland Township" subdivision of Alameda County. During this period, "Berkeley" was mostly a mix of open land, farms, and ranches, with a small, though busy, wharf by the bay.

Late 19th century

editIn 1866, Oakland's private College of California looked for a new site. It settled on a location north of Oakland along the foot of the Contra Costa Range (later called the Berkeley Hills) on Strawberry Creek, at an elevation of about 500 feet (150 m) above the bay, commanding a view of the Bay Area and the Pacific Ocean through the Golden Gate.

According to the Centennial Record of the University of California, "In 1866, at Founders' Rock, a group of College of California men watched two ships standing out to sea through the Golden Gate. One of them, Frederick Billings, thought of the lines of the Anglo-Irish Anglican Bishop George Berkeley, 'westward the course of empire takes its way,' and suggested that the town and college site be named for the eighteenth-century Anglo-Irish philosopher."[17] The philosopher's name is pronounced BARK-lee, but the city's name, to accommodate American English, is pronounced BERK-lee.[18]

The College of California's College Homestead Association planned to raise funds for the new campus by selling off adjacent parcels of land. To this end, they laid out a plat and street grid that became the basis of Berkeley's modern street plan. Their plans fell far short of their desires, and they began a collaboration with the State of California that culminated in 1868 with the creation of the public University of California.

As construction began on the new site, more residences were constructed in the vicinity of the new campus. At the same time, a settlement of residences, saloons, and various industries grew around the wharf area called Ocean View. A horsecar ran from Temescal in Oakland to the university campus along what is now Telegraph Avenue. The first post office opened in 1872.[19]

By the 1870s, the Transcontinental Railroad reached its terminus in Oakland. In 1876, a branch line of the Central Pacific Railroad, the Berkeley Branch Railroad, was laid from a junction with the mainline called Shellmound (now a part of Emeryville) into what is now downtown Berkeley. That same year, the mainline of the transcontinental railroad into Oakland was re-routed, putting the right-of-way along the bay shore through Ocean View.

There was a strong prohibition movement in Berkeley at this time. In 1876, the state enacted the "mile limit law", which forbade sale or public consumption of alcohol within one mile (1.6 km) of the new University of California.[20] Then, in 1899, Berkeley residents voted to make their city an alcohol-free zone. Scientists, scholars and religious leaders spoke vehemently of the dangers of alcohol.[21]

On April 1, 1878, the people of Ocean View and the area around the university campus, together with local farmers, were granted incorporation by the State of California as the Town of Berkeley.[22] The first elected trustees of the town were the slate of Denis Kearney's anti-Chinese Workingman's Party, who were particularly favored in the working-class area of the former Ocean View, now called West Berkeley. During the 1880s Berkeley had segregated housing and anti-Chinese laws.[23] The area near the university became known for a time as East Berkeley.

Due to the influence of the university, the modern age came quickly to Berkeley. Electric lights and the telephone were in use by 1888. Electric streetcars soon replaced the horsecar. A silent film of one of these early streetcars in Berkeley can be seen at the Library of Congress website.[24]

Early 20th century

editBerkeley's slow growth ended abruptly with the Great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. The town and other parts of the East Bay escaped serious damage, and thousands of refugees flowed across the Bay. Among them were most of San Francisco's painters and sculptors, who between 1907 and 1911 created one of the largest art colonies west of Chicago. Artist and critic Jennie V. Cannon described the founding of the Berkeley Art Association and the rivalries of competing studios and art clubs.[25]

In 1904, the first hospitals in Berkeley were created: the Alta Bates Sanatorium (today Alta Bates Summit Medical Center) for women and children, founded by nurse Alta Bates on Walnut Street, and the Roosevelt Hospital (later Herrick Hospital), founded by LeRoy Francis Herrick, on the corner of Dwight Way and Milvia Street.[26][27]

In 1908, a statewide referendum that proposed moving the California state capital to Berkeley was defeated by a margin of about 33,000 votes.[28] The city had named streets around the proposed capitol grounds for California counties. They bear those names today, a legacy of the failed referendum.

On March 4, 1909, following public referendums, the citizens of Berkeley were granted a new charter by the State of California, and the Town of Berkeley became the City of Berkeley.[29] Rapid growth continued up to the Crash of 1929. The Great Depression hit Berkeley hard, but not as hard as many other places in the U.S., thanks in part to the university.

In 1916, Berkeley implemented single-family zoning as an effort to keep minorities out of white neighborhoods. This has been described as the first implementation of single-family zoning in the United States[30][31][32] By 2021, nearly half of Berkeley's residential neighborhoods were still exclusively zoned for single-family homes.[33]

On September 17, 1923, a major fire swept down the hills toward the university campus and the downtown section. Around 640 structures burned before a late-afternoon sea breeze stopped its progress, allowing firefighters to put it out.

The next big growth occurred with the advent of World War II, when large numbers of people moved to the Bay Area to work in the many war industries, such as the immense Kaiser Shipyards in nearby Richmond. One who moved out, but played a big role in the outcome of the war, was U.C. professor and Berkeley resident J. Robert Oppenheimer. During the war, an Army base, Camp Ashby, was temporarily sited in Berkeley.

The element berkelium was synthesized utilizing the 60-inch (1.5 m) cyclotron at UC Berkeley, and named in 1949, in recognition of the university, thus placing the city's name in the list of elements.

1940–60s

editDuring the 1940s, many African Americans migrated to Berkeley.[34] In 1950, the Census Bureau reported Berkeley's population as 11.7% black and 84.6% white.[35]

The postwar years brought moderate growth to the city, as events on the U.C. campus began to build up to the recognizable activism of the sixties. In the 1950s, McCarthyism induced the university to demand a loyalty oath from its professors, many of whom refused to sign the oath on the principle of freedom of thought. In 1960, a U.S. House committee (HUAC) came to San Francisco to investigate the influence of communists in the Bay Area. Their presence was met by protesters, including many from the university. Meanwhile, a number of U.C. students became active in the civil rights movement. Finally, in 1964, the university provoked a massive student protest by banning distribution of political literature on campus. This protest became the Free Speech Movement. As the Vietnam War rapidly escalated in the ensuing years, so did student activism at the university, particularly that organized by the Vietnam Day Committee.

Berkeley is strongly identified with the rapid social changes, civic unrest, and political upheaval that characterized the mid-to-late 1960s.[36] In that period, Berkeley—especially Telegraph Avenue—became a focal point for the hippie movement, which spilled over the Bay from San Francisco. Many hippies were apolitical drop-outs, rather than students, but in the heady atmosphere of Berkeley in 1967–1969 there was considerable overlap between the hippie movement and the radical left. An iconic event in the Berkeley Sixties scene was a conflict over a parcel of university property south of the contiguous campus site that came to be called "People's Park".

The battle over the disposition of People's Park resulted in a month-long occupation of Berkeley by the National Guard on orders of then-Governor Ronald Reagan. In the end, the park remained undeveloped, and remains so today. A spin-off, People's Park Annex, was established at the same time by activist citizens of Berkeley on a strip of land above the Bay Area Rapid Transit ("BART") underground construction along Hearst Avenue northwest of the U.C. campus. The land had also been intended for development, but was turned over to the city by BART and is now Ohlone Park.

The era of large public protest in Berkeley waned considerably with the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. While the 1960s were the heyday of liberal activism in Berkeley, it remains one of the most overwhelmingly Democratic cities in the United States.

1970s and 1980s

editHousing and zoning changes

editAfter the 1960s, Berkeley banned most new housing construction, in particular apartments.[37]

Increasing enrollment at the university led to replacement of older buildings by large apartment buildings, especially in older parts of the city near the university and downtown. Increasing enrollment also led the university to wanting to redevelop certain places of Berkeley, especially Southside, but more specifically People's Park.[38] Preservationists passed the Neighborhood Protection Ordinance in 1973 by ballot measure and the Landmarks Preservation Ordinance in 1974 by the City Council. Together, these ordinances brought most new construction to a halt.[39] Facing rising housing costs, residents voted to enact rent control and vacancy control in 1980.[40] Though more far-reaching in their effect than those of some of the other jurisdictions in California that chose to use rent control where they could, these policies were limited by the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a statewide ban on rent control that came into effect in 1995 and limited rent control to multi-family units that were built (or technically buildings that were issued their original certificate of occupation) before the state law came into effect in 1995. For cities such as Berkeley, where rent control was already in place, the law limited the use of rent control to units built before the local rent-control law was enacted, i.e. 1980.[41]

Political movements

editDuring the 1970s and 1980s, activists increased their power in local government. This era also saw major developments in Berkeley's environmental and food culture. Berkeley's last Republican mayor, Wallace J. S. Johnson, left office in 1971. Alice Waters opened Chez Panisse in 1971. The first curbside recycling program in the U.S. was started by the Ecology Center in 1973. Styrofoam was banned in 1988.[42]

As the city leaned more and more Democratic, local politics became divided between "Progressives" and "Moderates". 1984 saw the Progressives take the majority for the first time. Nancy Skinner became the first UC Berkeley student elected to City Council. In 1986, in reaction to the 1984 election, a ballot measure switched Berkeley from at-large to district-based elections for city council.[43]

In 1983, Berkeley's Domestic Partner Task Force was established, which in 1984 made policy recommendation to the school board, which passed domestic partner legislation. The legislation became a model for similar measures nationwide.[44]

1990s and 2000s

editIn 1995, California's Costa–Hawkins Act ended vacancy control, allowing rents to increase when a tenant moved out. Despite a slow down in 2005–2007, median home prices and rents remain dramatically higher than the rest of the nation,[45] fueled by spillover from the San Francisco housing shortage and population growth.

South and West Berkeley underwent gentrification, with some historically Black neighborhoods such as the Adeline Corridor seeing a 50% decline in Black / African American population from 1990 to 2010.[46] In the 1990s, public television's Frontline documentary series featured race relations at Berkeley's only public high school, Berkeley High School.[47]

With an economy dominated by the University of California and a high-demand housing market, Berkeley was relatively unaffected by the Great Recession. State budget cuts caused the university to increase the number of out-of-state and international students, with international enrollment, mostly from Asia, rising from 2,785 in 2007 to 5,951 in 2016.[48] Since then, more international restaurants have opened downtown and on Telegraph Avenue, including East Asian chains such as Ippudo and Daiso.

A wave of downtown apartment construction began in 1998.[49]

In 2006, the Berkeley Oak Grove Protest began protesting construction of a new sports center annex to Memorial Stadium at the expense of a grove of oak trees on the UC campus. The protest ended in September 2008 after a lengthy court process.

In 2007–2008, Berkeley received media attention due to demonstrations against a Marine Corps recruiting office in downtown Berkeley and a series of controversial motions by Berkeley's city council regarding opposition to Marine recruiting. (See Berkeley Marine Corps Recruiting Center controversy.)

2010s and 2020s

editDuring the fall of 2010, the Berkeley Student Food Collective opened after many protests on the UC Berkeley campus due to the proposed opening of the fast food chain Panda Express. Students and community members worked together to open a collectively run grocery store right off of the UC Berkeley campus, where the community can buy local, seasonal, humane, and organic foods. The Berkeley Student Food Collective still operates at 2440 Bancroft Way.

On September 18, 2012, Berkeley became what may be the first city in the U.S. to officially proclaim a day recognizing bisexuals: September 23, which is known as Celebrate Bisexuality Day.[50]

On September 2, 2014, the city council approved a measure to provide free medical marijuana to low-income patients.[51]

The Measure D soda tax was approved by Berkeley voters on November 4, 2014, the first such tax in the United States.[52]

Protests

editIn the fall of 2011, the nationwide Occupy Wall Street movement came to two Berkeley locations: on the campus of the University of California and as an encampment in Civic Center Park.

During a Black Lives Matter protest on December 6, 2014, police use of tear gas and batons to clear protesters from Telegraph Avenue led to a riot and five consecutive days and nights of protests, marches, and freeway occupations in Berkeley and Oakland.[53] Afterwards, changes were implemented by the Police Department to avoid escalation of violence and to protect bystanders during protests.[54]

During a protest against bigotry and U.S. President Donald Trump in August 2017, self-described anti-fascist protesters attacked Trump supporters in attendance. Police intervened, arresting 14 people. Sometimes called "antifa", these ‘anti-fascist’ activists were clad in black shirts and other black attire, while some carried shields and others had masks or bandanas hiding their faces to help them evade capture after street fighting. .[55] These protests spanned February to September 2017 (See more at 2017 Berkeley Protests).[56]

In 2019, protesters took up residence in People's Park against tree-chopping and were arrested by police in riot gear. Many activists saw this as the university preparing to develop the park.[57]

Homelessness

editThe city of Berkeley has historically been a central location for homeless communities in the Bay Area.[58] Since the 1930s, the city of Berkeley has fostered a tradition of political activism.[59] The city has been perceived as a hub for liberal thought and action and it has passed ordinances to oust homeless individuals from Berkeley on multiple occasions.[60] Despite efforts to remove unhoused individuals from the streets and projects to improve social service provision for this demographic, homelessness has continued to be a significant problem in Berkeley.[61]

1960s

editA culture of anti-establishment and sociopolitical activism marked the 1960s.[59] The San Francisco Bay Area became a hotspot for hippie counterculture, and Berkeley became a haven for nonconformists and anarchists[59] from all over the United States.[62] Most public discourse around homelessness in Berkeley at this time was centered around the idea of street-living as an expression of counterculture.[58]

During the Free Speech Movement in the fall of 1964, Berkeley became a hub of civil unrest, with demonstrators and UC Berkeley students sympathizing with the statewide protests for free speech and assembly, as well as revolting against university restrictions against student political activities and organizations established by UC President Clark Kerr in 1959. Many non-student youth and adolescents sought alternative lifestyles and opted for voluntary homelessness during this time.[63][64]

In 1969, People's Park was created and eventually became a haven for "small-time drug dealers, street people, and the homeless".[65] Although the City of Berkeley has moved unhoused individuals from its streets, sometimes even relocating them to an unused landfill, People's Park has remained a safe space for them since its inception.[65] The park has become one of the few relatively safe spaces for homeless individuals to congregate in Berkeley and the greater Bay Area.[65]

1970s

editStereotypes of homeless people as deviant individuals who chose to live vagrant lifestyles continued to color the discourse around street-dwellers in American cities.[58] However, this time period was also characterized by a subtle shift in the perception of unhoused individuals. The public began to realize that homelessness affected not only single men, but also women, children, and entire families.[58] This recognition set the stage for the City of Berkeley's attitude towards homelessness in the next decade.[66]

1980s

editOrganizations such as Building Opportunities for Self Sufficiency (BOSS) were established in 1971 in response to the needs of individuals with mental illness being released to the streets by state hospital closures.[67]

1990s

editIn the 1990s, the City of Berkeley faced a substantial increase in the need for emergency housing shelters and saw a rise in the average amount of time individuals spent without stable housing.[60] As housing became a more widespread problem, the general public, Berkeley City Council, and the University of California became increasingly anti-homeless in their opinions.[60] In 1994, Berkeley City Council considered the implementation of a set of anti-homeless laws that the San Francisco Chronicle described as being "among the strictest in the country".[58] These laws prohibited sitting, sleeping and begging in public spaces, and outlawed panhandling from people in a variety of contexts, such as sitting on public benches, buying a newspaper from a rack, or waiting in line for a movie.[58] In February 1995, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued the city for infringing free speech rights through its proposed anti-panhandling law.[58] In May of that same year, a federal judge ruled that the anti-panhandling law did violate the First Amendment, but left the anti-sitting and sleeping laws untouched.[58]

Following the implementation of these anti-sitting and sleeping ordinances in 1998, Berkeley increased its policing of homeless adults and youth, particularly in the shopping district surrounding Telegraph Avenue.[68] The mayor at that time, Shirley Dean, proposed a plan to increase both social support services for homeless youth and enforcement of anti-encampment laws.[68] Unhoused youth countered this plan with a request for the establishment of the city's first youth shelter, more trash cans, and more frequent cleaning of public bathrooms.[68]

21st century

editThe City of Berkeley's 2017 annual homeless report and point-in-time count (PIT) estimate that on a given night, 972 people are homeless.[69] Sixty-eight percent (664 people) of these individuals are also unsheltered, living in places not considered suitable for human habitation, such as cars or streets.[69] Long-term homelessness in Berkeley is double the national average, with 27% of the city's homeless population facing chronic homelessness.[69] Chronic homelessness has been on the rise since 2015, and has been largely a consequence of the constrained local housing market.[69] In 2015, rent in Alameda County increased by 25%, while the average household income only grew by 5%.[70] The City of Berkeley's 2017 report also estimated the number of unaccompanied youth in Berkeley at 189 individuals, 19% of the total homeless population in the city. Homeless youth display greater risk of mental health issues, behavioral problems, and substance abuse, than any other homeless age group.[64] Furthermore, homeless youth identifying as LGBTQ+ are exposed to greater rates of physical and sexual abuse, and higher risk for sexually-transmitted diseases, predominantly HIV.[71][72]

The City of Berkeley has seen a consistent rise in the number of chronically homeless individuals over the past 30 years, and has implemented a number of different projects to reduce the number of people living on the streets.[73] In 2008, the City focused its efforts on addressing chronic homelessness. This led to a 48% decline in the number of chronically homeless individuals reported in the 2009 Berkeley PIT.[74] However, the number of "hidden homeless" individuals (those coping with housing insecurity by staying at a friend or relative's residence), increased significantly, likely in response to rising housing costs and costs of living.[74] In 2012, the City considered measures that banned sitting in commercial areas throughout Berkeley.[74] The measure was met with strong public opposition and did not pass. However, the City saw a strong need for it to implement rules addressing encampments and public usage of space as well as assessing the resources needed to assist the unhoused population.[74] In response to these needs the City of Berkeley established the Homeless Task Force, headed by then-Councilmember Jesse Arreguín.[74] Since its formation, the Task Force has proposed a number of different recommendations, from expanding the City Homeless Outreach and Mobile Crisis Teams, to building a short-term transitional shelter for unhoused individuals.[75]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city's 17.7-square-mile (46 km2) area includes 10.5 square miles (27 km2) of land and 7.2 square miles (19 km2) (40.83%) water, most of it part of San Francisco Bay.

Berkeley borders the cities of Albany, Oakland, and Emeryville and Contra Costa County, including unincorporated Kensington, as well as San Francisco Bay.

Berkeley lies within telephone area code 510 (until September 2, 1991, Berkeley was part of the 415 telephone code that now covers only San Francisco and Marin counties[76]), and the postal ZIP codes are 94701 through 94710, 94712, and 94720 for the University of California campus.[11]

Geology

editMost of Berkeley lies on a rolling sedimentary plain that rises gently from sea level to the base of the Berkeley Hills. East of the Hayward Fault along the base of the hills, elevation increases more rapidly. The highest peak along the ridge line above Berkeley is Grizzly Peak, at an elevation of 1,754 feet (535 m). A number of small creeks run from the hills to the Bay through Berkeley: Cerrito, Codornices, Schoolhouse, and Strawberry Creeks are the principal streams. Most of these are largely culverted once they reach the plain west of the hills.

The Berkeley Hills are part of the Pacific Coast Ranges, and run in a northwest–southeast alignment. Exposed in the Berkeley Hills are cherts and shales of the Claremont Formation (equivalent to the Monterey Formation), conglomerate and sandstone of the Orinda Formation and lava flows of the Moraga Volcanics. Of similar age to the Moraga Volcanics (extinct), within the Northbrae neighborhood of Berkeley, are outcroppings of erosion resistant rhyolite. These rhyolite formations can be seen in several city parks and in the yards of a number of private residences. Indian Rock Park in the northeastern part of Berkeley near the Arlington/Marin Circle features a large example.

Earthquakes

editBerkeley is traversed by the Hayward Fault Zone, a major branch of the San Andreas Fault to the west. No large earthquake has occurred on the Hayward Fault near Berkeley in historic times (except possibly in 1836), but seismologists warn about the geologic record of large temblors several times in the deeper past. The current assessment is that a Bay Area earthquake of magnitude 6.7 or greater within the next 30 years is likely, with the Hayward Fault having the highest likelihood among faults in the Bay Area of being the epicenter.[77] Moreover, like much of the Bay Area, Berkeley has many areas of some risk to soil liquefaction, with the flat areas closer to the shore at low to high susceptibility.[78]

The 1868 Hayward earthquake did occur on the southern segment of the Hayward Fault[79] in the vicinity of today's city of Hayward. This quake destroyed the county seat of Alameda County then located in San Leandro and it subsequently moved to Oakland. It was strongly felt in San Francisco, causing major damage. It was regarded as the "Great San Francisco earthquake" prior to 1906. It produced a furrow in the ground along the fault line in Berkeley, across the grounds of the new State Asylum for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind then under construction, which was noted by one early University of California professor. Although no significant damage was reported to most of the few Berkeley buildings of the time, the 1868 quake did destroy the vulnerable adobe home of Domingo Peralta in north Berkeley.[80]

Today, evidence of the Hayward Fault's "creeping" is visible at various locations in Berkeley. Cracked roadways, sharp jogs in streams, and springs mark the fault's path. However, since it cuts across the base of the hills, the creep is often concealed by or confused with slide activity. Some of the slide activity itself, however, results from movement on the Hayward Fault.

A notorious segment of the Hayward Fault runs lengthwise down the middle of Memorial Stadium at the mouth of Strawberry Canyon on the University of California campus.[81] Photos and measurements show the movement of the fault through the stadium.[82]

Climate

editBerkeley has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb in the Köppen climate classification), with warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters. Berkeley's location directly opposite the Golden Gate ensures that typical eastward fog flow blankets the city more often than its neighbors.[83] The summers are cooler than a typical Mediterranean climate thanks to upwelling ocean currents along the California coast. These help produce cool and foggy nights and mornings.

Winter is punctuated with rainstorms of varying ferocity and duration, but also produces stretches of bright sunny days and clear cold nights. It does not normally snow, though occasionally the hilltops get a dusting. Spring and fall are transitional and intermediate, with some rainfall and variable temperature. Summer typically brings night and morning low clouds or fog, followed by sunny, warm days. The warmest and driest months are typically June through September, with the highest temperatures occurring in September. Mid-summer (July–August) is often a bit cooler due to the sea breezes and fog common then.

In a year, there are an average of 2.9 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher, and an average of 0.8 days with lows of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower. The highest recorded temperature was 107 °F (42 °C) on June 15, 2000, and July 16, 1993, and the lowest recorded temperature was 24 °F (−4 °C) on December 22, 1990.

February is normally the wettest month, averaging 5.21 inches (132 mm) of precipitation. Average annual precipitation is 25.40 inches (645 mm), falling on an average of 63.7 days each year. The most rainfall in one month was 14.49 inches (368 mm) in February 1998. The most rainfall in 24 hours was 6.98 inches (177 mm) on January 4, 1982.[84] As in most of California, the heaviest rainfall years are usually associated with warm water El Niño episodes in the Pacific (e.g., 1982–83; 1997–98), which bring in drenching "Pineapple Express" storms. In contrast, dry years are often associated with cold Pacific La Niña episodes. Light snow has fallen on rare occasions. Snow has generally fallen every several years on the higher peaks of the Berkeley Hills.[85]

In the late spring and early fall, strong offshore winds of sinking air typically develop, bringing heat and dryness to the area. In the spring, this is not usually a problem as vegetation is still moist from winter rains, but extreme dryness prevails by the fall, creating a danger of wildfires. In September 1923, a major fire swept through the neighborhoods north of the university campus, stopping just short of downtown. On October 20, 1991, gusty, hot winds fanned a conflagration along the Berkeley–Oakland border, killing 25 people and injuring 150, as well as destroying 2,449 single-family dwellings and 437 apartment and condominium units.

| Climate data for Berkeley, California (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

81 (27) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

107 (42) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

99 (37) |

86 (30) |

78 (26) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.7 (19.3) |

72.1 (22.3) |

77.1 (25.1) |

82.0 (27.8) |

86.0 (30.0) |

90.9 (32.7) |

87.1 (30.6) |

89.0 (31.7) |

91.7 (33.2) |

87.6 (30.9) |

76.4 (24.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

95.6 (35.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.9 (14.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

64.6 (18.1) |

67.3 (19.6) |

70.0 (21.1) |

74.1 (23.4) |

74.2 (23.4) |

74.7 (23.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

73.4 (23.0) |

65.2 (18.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

68.2 (20.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

53.0 (11.7) |

55.2 (12.9) |

57.0 (13.9) |

59.7 (15.4) |

62.9 (17.2) |

63.7 (17.6) |

64.4 (18.0) |

64.9 (18.3) |

62.5 (16.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

50.9 (10.5) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 43.3 (6.3) |

44.5 (6.9) |

45.9 (7.7) |

46.7 (8.2) |

49.4 (9.7) |

51.7 (10.9) |

53.2 (11.8) |

54.2 (12.3) |

53.6 (12.0) |

51.6 (10.9) |

46.9 (8.3) |

43.2 (6.2) |

48.7 (9.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 36.2 (2.3) |

37.0 (2.8) |

38.8 (3.8) |

40.4 (4.7) |

44.9 (7.2) |

47.7 (8.7) |

50.1 (10.1) |

51.2 (10.7) |

49.4 (9.7) |

45.8 (7.7) |

40.0 (4.4) |

35.6 (2.0) |

33.4 (0.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 25 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

33 (1) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

40 (4) |

46 (8) |

38 (3) |

39 (4) |

33 (1) |

24 (−4) |

24 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.84 (123) |

5.12 (130) |

3.84 (98) |

1.83 (46) |

0.80 (20) |

0.26 (6.6) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.12 (3.0) |

1.19 (30) |

2.74 (70) |

5.32 (135) |

26.12 (663) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 10.5 | 9.8 | 7.0 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 11.0 | 66.6 |

| Source: NOAA[86][87] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 5,101 | — | |

| 1900 | 13,214 | 159.0% | |

| 1910 | 40,434 | 206.0% | |

| 1920 | 56,036 | 38.6% | |

| 1930 | 82,109 | 46.5% | |

| 1940 | 85,547 | 4.2% | |

| 1950 | 113,805 | 33.0% | |

| 1960 | 111,268 | −2.2% | |

| 1970 | 114,091 | 2.5% | |

| 1980 | 103,328 | −9.4% | |

| 1990 | 102,724 | −0.6% | |

| 2000 | 102,743 | 0.0% | |

| 2010 | 112,580 | 9.6% | |

| 2020 | 124,321 | 10.4% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 125,327 | [88] | 0.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[89] | |||

2020 census and estimates

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[90] | Pop 2010[91] | Pop 2020[92] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 56,691 | 61,539 | 62,450 | 55.18% | 54.66% | 50.23% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 13,707 | 10,896 | 9,495 | 13.34% | 9.68% | 7.64% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 293 | 228 | 226 | 0.29% | 0.20% | 0.18% |

| Asian (NH) | 16,740 | 21,499 | 24,701 | 16.29% | 19.10% | 19.87% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 121 | 170 | 253 | 0.12% | 0.15% | 0.20% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 598 | 503 | 1,109 | 0.58% | 0.45% | 0.89% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 4,592 | 5,536 | 9,069 | 4.47% | 4.92% | 7.29% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 10,001 | 12,209 | 17,018 | 9.73% | 10.84% | 13.69% |

| Total | 102,743 | 112,580 | 124,321 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

The 2020 United States Census[93] reported that Berkeley had a population of 124,321. The population density was 11,874 people per square mile of land area (4,584/km2). The racial and ethnic makeup (where Latinos are excluded from the racial counts and treated as if a separate race) of Berkeley was 62,450 (50.2%) White, 9,495 (7.6%) Black or African American, 24,701 (19.9%) Asian, 253 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 226 (0.2%) from Native American, 1,109 (0.9%) from other races, and 9,069 (7.2%) multiracial (two or more races). There were 17,018 (13.7%) of Hispanic or Latino ancestry, of any race.

According to the 2022 American Community Survey[94] estimate, the median income for a household was $104,716 and the median income for a family was $177,068. Males had a median income of $102,565 versus $82,772 for females. The per capita income for the city was $63,310. About 4.3% of families and 17.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6% of those under age 18 and 8.1% of those age 65 or over.

Earlier census data

editFrom the 2010 United States Census,[95] the racial makeup of Berkeley was 66,996 (59.5%) White, 11,241 (10.0%) Black or African American, 479 (0.4%) Native American, 21,690 (19.3%) Asian (8.4% Chinese, 2.4% Indian, 2.1% Korean, 1.6% Japanese, 1.5% Filipino, 1.0% Vietnamese), 186 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 4,994 (4.4%) from other races, and 6,994 (6.2%) from two or more races. There were 12,209 people (10.8%) of Hispanic or Latino ancestry, of any race. 6.8% of the city's population was of Mexican ancestry.

The Census reported that 99,731 people (88.6% of the population) lived in households, 12,430 (11.0%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 419 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 46,029 households, out of which 8,467 (18.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 13,569 (29.5%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 3,855 (8.4%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,368 (3.0%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 2,931 (6.4%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 961 (2.1%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 16,904 households (36.7%) were made up of individuals, and 4,578 (9.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17. There were 18,792 families (40.8% of all households); the average family size was 2.81. There were 49,454 housing units at an average density of 2,794.6 per square mile (1,079.0/km2), of which 46,029 were occupied, of which 18,846 (40.9%) were owner-occupied, and 27,183 (59.1%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.5%. 45,096 people (40.1% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 54,635 people (48.5%) lived in rental housing units.

In the city, 13,872 people (12.3%) were under the age of 18, 30,295 people (26.9%) were aged 18 to 24, 30,231 people (26.9%) aged 25 to 44, 25,006 people (22.2%) aged 45 to 64, and 13,176 people (11.7%) were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.2 males.

According to the 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $60,908, and the median income for a family was $102,976.[96] Males had a median income of $67,476 versus $57,319 for females. The per capita income for the city was $38,896. About 7.2% of families and 18.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.2% of those under age 18 and 9.2% of those age 65 or over.

Berkeley has a higher-than-average crime rate, particularly property crime,[97] though the crime rate has fallen significantly since 2000.[98]

Transportation

editBerkeley is served by Amtrak (Capitol Corridor), AC Transit, BART (Ashby, Downtown Berkeley Station and North Berkeley) and bus shuttles operated by major employers including UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The Eastshore Freeway (Interstate 80 and Interstate 580) runs along the bay shoreline. Each day there is an influx of thousands of cars into the city by commuting UC faculty, staff and students, making parking for more than a few hours an expensive proposition.

Berkeley has one of the highest rates of bicycle and pedestrian commuting in the nation. Berkeley is the safest city of its size in California for pedestrians and cyclists, considering the number of injuries per pedestrian and cyclist, rather than per capita.[99]

Berkeley has modified its original grid roadway structure through use of diverters and barriers, moving most traffic out of neighborhoods and onto arterial streets (visitors often find this confusing, because the diverters are not shown on all maps). Berkeley maintains a separate grid of arterial streets for bicycles, called Bicycle Boulevards, with bike lanes and lower amounts of car traffic than the major streets they often parallel. Attempts to improve the biking infrastructure in Berkeley have been met with controversy. In 2023, the Berkeley city council fired the city's top transportation official for a plan to remove dozens of parking spots on a street to build a protected bike lane.[100]

Berkeley hosts car sharing networks including Uhaul Car Share, Gig Car Share, and Zipcar. Rather than owning (and parking) their own cars, members share a group of cars parked nearby. Web- and telephone-based reservation systems keep track of hours and charges. Several "pods" (points of departure where cars are kept) exist throughout the city, in several downtown locations, at the Ashby and North Berkeley BART stations, and at various other locations in Berkeley (and other cities in the region). Using alternative transportation is encouraged.

Berkeley has had recurring problems with parking meter vandalism. In 1999, over 2,400 Berkeley meters were jammed, smashed, or sawed apart.[101] Starting in 2005 and continuing into 2006, Berkeley began to phase out mechanical meters in favor of more centralized electronic meters.

Transportation history

editThe first commuter service to San Francisco was provided by the Central Pacific's Berkeley Branch Railroad, a standard gauge steam railroad, which terminated in downtown Berkeley, and connected in Emeryville (at a locale then known as "Shellmound") with trains to the Oakland ferry pier as well as with the Central Pacific main line starting in 1876. The Berkeley Branch line was extended from Shattuck and University to Vine Street ("Berryman's Station") in 1878. Starting in 1882, Berkeley trains ran directly to the Oakland Pier.[102] In the 1880s, Southern Pacific assumed operations of the Berkeley Branch under a lease from its own paper affiliate, the Northern Railway. In 1911, Southern Pacific electrified this line and the several others it constructed in Berkeley, creating its East Bay Electric Lines division. The huge and heavy cars specially built for these lines were called the "Red Trains" or the "Big Red Cars". The Shattuck line was extended and connected with two other Berkeley lines (the Ninth Street Line and the California Street line) at Solano and Colusa (the "Colusa Wye"). At this time, the Northbrae Tunnel and Rose Street Undercrossing were constructed, both of which still exist. (The Rose Street Undercrossing is not accessible to the public, being situated between what is now two backyards.) The fourth Berkeley line was the Ellsworth St. line to the university campus. The last Red Trains ran in July 1941.[103]

The first electric rail service in Berkeley was provided by several small streetcar companies starting in 1891. Most of these were eventually bought up by the Key System of Francis "Borax" Smith who added lines and improved equipment. The Key System's streetcars were operated by its East Bay Street Railways division. Principal lines in Berkeley ran on Euclid, The Arlington, College, Telegraph, Shattuck, San Pablo, University, and Grove (today's Martin Luther King Jr. Way). The last streetcars ran in 1948, replaced by buses.

The first electric commuter interurban-type trains to San Francisco from Berkeley were put in operation by the Key System in 1903, several years before the Southern Pacific electrified its steam commuter lines. Like the SP, Key trains ran to a pier serviced by the Key's own fleet of ferryboats, which also docked at the Ferry Building in San Francisco. After the Bay Bridge was built, the Key trains ran to the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco, sharing tracks on the lower deck of the Bay Bridge with the SP's red trains and the Sacramento Northern Railroad. It was at this time that the Key trains acquired their letter designations, which were later preserved by Key's public successor, AC Transit. Today's F bus is the successor of the F train. Likewise, the E, G and the H. Before the Bridge, these lines were simply the Shattuck Avenue Line, the Claremont Line, the Westbrae Line, and the Sacramento Street Line, respectively.

After the Southern Pacific abandoned transbay service in 1941, the Key System acquired the rights to use its tracks and catenary on Shattuck north of Dwight Way and through the Northbrae Tunnel to The Alameda for the F-train. The SP tracks along Monterey Avenue as far as Colusa had been acquired by the Key System in 1933 for the H-train, but were abandoned in 1941. The Key System trains stopped running in April 1958.[104] On December 15, 1962, the Northbrae Tunnel was opened to auto traffic.[105]

Economy

editTop employers

editAccording to the city's 2021 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[106] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of California, Berkeley | 13,669 |

| 2 | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | 3,836 |

| 3 | Alta Bates Summit Medical Center (part of Sutter Health) | 2,040 |

| 4 | City of Berkeley | 1,480 |

| 5 | Bayer | 1,082 |

| 6 | Berkeley Unified School District | 865 |

| 7 | Kaiser Permanente | 771 |

| 8 | Siemens | 678 |

| 9 | Berkeley Bowl | 558 |

| 10 | Lifelong Medical Care | 441 |

Businesses

editBerkeley is the location of a number of nationally prominent businesses, many of which have been pioneers in their areas of operation. Notable businesses include Chez Panisse, birthplace of California cuisine, Peet's Coffee's original store, the Claremont Resort, punk rock haven 924 Gilman, Saul Zaentz's Fantasy Studios, and Caffe Strada. Notable former businesses include pioneer bookseller Cody's Books, The Nature Company, The North Face, Clif Bar energy foods, the Berkeley Co-op, and Caffe Mediterraneum.

Berkeley has relatively few chain stores for a city of its size, due to policies and zoning that promote small businesses[107] and impose limits on the size of certain types of stores.[108]

Places

editMajor streets

edit- Shattuck Avenue passes through several neighborhoods from north to south, including the downtown business district in Berkeley. It is named for Francis K. Shattuck, one of Berkeley's earliest influential citizens and the most prominent civic leader in the early history of Berkeley. He played an important role in the creation and government of Alameda County as well.

- University Avenue runs from Berkeley's bayshore and marina in the west to the University of California campus in the east.

- College Avenue, running from the University of California from the north to Broadway in Oakland in the south close to the foothill, is a relatively quiet street compared with other major streets in Berkeley. It supports many restaurants and small shops.

- Ashby Avenue (Highway 13), which also runs from Berkeley's bayshore to the hills, connects with the Warren Freeway and Highway 24 leading to the Caldecott Tunnel, named for a former Berkeley mayor.

- San Pablo Avenue (Highway 123) runs north–south through West Berkeley, connecting Oakland and Emeryville to the south and Albany to the north.

- Telegraph Avenue, which runs north–south from the university campus to Oakland, historically the site of much of the hippie culture of Berkeley.

- Martin Luther King Jr. Way, which until 1984 was called Grove Street, runs north–south a few blocks west of Shattuck Avenue, connecting Oakland and the freeways to the south with the neighborhoods and other communities to the north.

- Sacramento Street is one of the four streets with a median in Berkeley, running from Hopkins Street from the north to Alcatraz Ave in the south.

- Solano Avenue, a major street for shopping and restaurants, runs east–west near the north end of Berkeley, continuing into Albany. Since 1974, Solano Avenue has hosted the annual Solano Avenue Stroll and Parade[109] of the twin-cities of Albany and Berkeley, the East Bay's largest street festival.

Freeways

edit- The Eastshore Freeway (I-80 and I-580) runs along Berkeley's bayshore with exits at Ashby Avenue, University Avenue and Gilman Street.

Bicycle and pedestrian paths

edit- Ohlone Greenway

- San Francisco Bay Trail

- Berkeley I-80 bridge – opened in 2002, an arch-suspension bridge spanning Interstate 80, for bicycles and pedestrians only, giving access from the city at the foot of Addison Street to the San Francisco Bay Trail, the Eastshore State Park and the Berkeley Marina.

- Berkeley's Network of Historic Pathways – Berkeley has a network of historic pathways that link the winding neighborhoods found in the hills and offer panoramic lookouts over the East Bay. A complete guide to the pathways may be found at Berkeley Path Wanderers Association website.[110]

Neighborhoods

editBerkeley has a number of distinct neighborhoods. Surrounding the University of California campus are the most densely populated parts of the city. West of the campus is Downtown Berkeley, the city's traditional commercial core; home of the civic center, the city's only public high school, the busiest BART station in Berkeley, as well as a major transfer point for AC Transit buses. South of the campus is Southside, mainly a student ghetto, where much of the university's student housing is located. The busiest stretch of Telegraph Avenue is in this neighborhood. North of the campus is the quieter Northside neighborhood, the location of the Graduate Theological Union.

Farther from the university campus, the influence of the university quickly becomes less visible. Most of Berkeley's neighborhoods are primarily made up of detached houses, often with separate in-law units in the rear, although larger apartment buildings are also common in many neighborhoods. Commercial activities are concentrated along the major avenues and at important intersections and frequently define the neighborhood within which they reside.

In the southeastern corner of the city is the Claremont District, home to the Claremont Hotel. Also in the southeast is the Elmwood District known for its commercial area on College Avenue. West of Elmwood is South Berkeley, known for its weekend flea market at the Ashby Station.

West of (and including) San Pablo Avenue, itself a major commercial and transport corridor, is West Berkeley, the historic commercial center of the city. This neighborhood and area includes the former unincorporated town of Ocean View. West Berkeley contains the remnants of Berkeley's industrial area, much of which has been replaced by retail and office uses, as well as residential live/work loft space, paralleling the decline of manufacturing in the United States. This area abuts the shoreline of the San Francisco Bay and is home to the Berkeley Marina. Also nearby is Berkeley's Aquatic Park, featuring an artificial linear lagoon of San Francisco Bay.

North of downtown is North Berkeley which has its main commercial area nicknamed the "Gourmet Ghetto" because of the concentration of well-known restaurants and other food-related businesses. West of North Berkeley (roughly west of Sacramento and north of Cedar) is Westbrae, a small neighborhood centered on a small commercial area on Gilman Street and through which part of the Ohlone Greenway runs. Meanwhile, further north of North Berkeley are Northbrae, a master-planned subdivision from the early 20th century, and Thousand Oaks. Above these last three neighborhoods, on the western slopes of the Berkeley Hills are the neighborhoods of Cragmont and La Loma Park, notable for their dramatic views, winding streets, and numerous public stairways and paths.

Points of interest

edit- Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

- Berkeley Free Clinic, a free clinic operating since 1969.

- Berkeley High School

- Berkeley Historical Society and Museum (1931 Center St.)

- Berkeley Marina

- Berkeley Public Library (Shattuck Avenue at Kittredge Street)

- Berkeley Repertory Theatre

- Berkeley Rose Garden

- Cloyne Court Hotel, a member of the Berkeley Student Cooperative

- The Edible Schoolyard is a one-acre garden at Martin Luther King Middle School (Berkeley)

- Hearst Greek Theatre (home of the annual Berkeley Jazz Festival)

- Indian Rock Park

- Judah L. Magnes Museum

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

- Lawrence Hall of Science

- Regional Parks Botanic Garden

- Telegraph Avenue and People's Park, both known as centers of the counterculture of the 1960s

- Tilden Regional Park

- University of California, Berkeley

- The Campanile (Sather Tower) in the University of California, Berkeley campus.

- University of California Botanical Garden

- Urban Ore

Parks and recreation

editThe city has many parks, and promotes greenery and the environment. The city has planted trees for years and is a leader in the nationwide effort to re-tree urban areas.[citation needed] Tilden Regional Park, lies east of the city, occupying the upper extent of Wildcat Canyon between the Berkeley Hills and the San Pablo Ridge. The city is also heavily involved in creek restoration and wetlands restoration, including a planned daylighting of Strawberry Creek along Center Street. The Berkeley Marina and East Shore State Park flank its shoreline at San Francisco Bay and organizations like the Urban Creeks Council and Friends of the Five Creeks the former of which is headquartered in Berkeley support the riparian areas in the town and coastlines as well. César Chávez Park, near the Berkeley Marina, was built at the former site of the city dump.

Landmarks and historic districts

edit165 buildings in Berkeley are designated as local landmarks or local structures of merit. Of these, 49 are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including:

- Berkeley High School (the city's only public high school) and the Berkeley Community Theatre, which is on its campus.[111]

- Berkeley Women's City Club, now Berkeley City Club – Julia Morgan (1929–30)

- First Church of Christ, Scientist – Bernard Maybeck (1910)

- St. John's Presbyterian Church – Julia Morgan (1910), now the Berkeley Playhouse

- Studio Building – architect not recorded, built for Frederick H. Dakin (1905)

- Thorsen House (Sigma Phi Society of the Thorsen House) – Charles Sumner Greene & Henry Mather Greene (1908–10)

Historic districts listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

- George C. Edwards Stadium – Located at intersection of Bancroft Way and Fulton Street on University of California, Berkeley campus (80 acres (32 ha), 3 buildings, 4 structures, 3 objects; added 1993).

- Site of the Clark Kerr Campus, UC Berkeley – until 1980, this location housed the State Asylum for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind, also known as The California Schools for the Deaf and Blind – Bounded by Dwight Way, the city line, Derby Street, and Warring Street (500 acres (2.0 km2), 20 buildings; added 1982). The school was closed in 1980 and the Clark Kerr Campus was opened in 1986.

Arts and culture

editBerkeley is home to the Chilean-American community's La Peña Cultural Center, the largest cultural center for this community in the United States. The Freight and Salvage is the oldest established full-time folk and traditional music venue west of the Mississippi River.[112]

Additionally, Berkeley is home to the off-broadway theater Berkeley Repertory Theater, commonly known as "Berkeley Rep". The Berkeley Repertory Theater consists of two stages, a school, and has received a Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre.[113] The historic Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) is operated by UC Berkeley, and was moved to downtown Berkeley in January 2016. It offers many exhibitions and screenings of historic films, as well as outreach programs within the community.[114]

Annual events

edit- Jewish Music Festival[115] – March

- Cal Day, University of California, Berkeley Open House[116] – April

- Berkeley Arts Festival[117] – April and May

- Himalayan Fair[118] – May

- The Berkeley Juneteenth Festival – Adeline/Alcatraz Corridor – June

- Berkeley Kite Festival[119] – July

- Berkeley Juggling and Unicycling Festival[120] – July or August

- The Solano Avenue Stroll[121] – Solano Avenue, Berkeley and Albany – September

- The Bay Area Book Festival[122] – Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park and throughout Downtown Berkeley – May

Education

editColleges and universities

editUniversity of California, Berkeley's main campus is in the city limits.

The Graduate Theological Union, a consortium of eight independent theological schools, is located a block north of the University of California Berkeley's main campus. The Graduate Theological Union has the largest number of students and faculty of any religious studies doctoral program in the United States.[123] In addition to more theological schools, Zaytuna College, a newly established Muslim liberal arts college, has taken 'Holy Hill' as its new home. The Institute of Buddhist Studies has been located in Berkeley since 1966. Wright Institute, a psychology graduate school, is located in Berkeley. Berkeley City College is a community college in the Peralta Community College District.

Primary and secondary schools

editThe Berkeley Unified School District operates public schools.

The first public school in Berkeley was the Ocean View School, now the site of the Berkeley Adult School located at Virginia Street and San Pablo Avenue. The public schools today are administered by the Berkeley Unified School District. In the 1960s, Berkeley was one of the earliest US cities to voluntarily desegregate, utilizing a system of buses, still in use. The district has eleven elementary schools and one public high school, Berkeley High School (BHS). Established in 1880, BHS currently has over 3,000 students. The Berkeley High campus was designated a historic district by the National Register of Historic Places on January 7, 2008.[124] Saint Mary's College High School, a Catholic school, also has its street address in Berkeley, although most of the grounds and buildings are actually in neighboring Albany. Berkeley has 11 public elementary schools and three middle schools.

The East Bay campus of the German International School of Silicon Valley (GISSV) formerly occupied the Hillside Campus, Berkeley, California; it opened there in 2012.[125] In December 2016, the GISSV closed the building, due to unmet seismic retrofit needs.[126]

There is also the Bay Area Technology School, the only school in the whole Bay Area to offer a technology- and science-based curriculum, with connections to leading universities.

Berkeley also houses Zaytuna College, the first accredited Muslim, liberal-arts college in the United States.

Public libraries

editBerkeley Public Library serves as the municipal library. University of California, Berkeley Libraries operates the University of California Berkeley libraries.

Government

editBerkeley has a council–manager government.[2] The mayor is elected at-large for a four-year term and is the ceremonial head of the city and the chair of the city council. The Berkeley City Council is composed of the mayor and eight council members elected by district who each serve four-year terms. Districts 2, 3, 5 and 6 hold their elections in years divisible by four while Districts 1, 4, 7 and 8 hold theirs in even-numbered years not divisible by four. The city council appoints a city manager, who is the chief executive of the city. Additionally, the city voters directly elect an independent city auditor, school board, and rent stabilization board. Most city officials, including council members, are elected using instant-runoff voting since November 2010.

Kriss Worthington, elected in 1996 to represent District 7, became the first openly LGBT man elected to the Berkeley City Council. Lori Droste, elected in 2014 to represent District 8, became the first openly LGBT woman elected to the Berkeley City Council. Terry Taplin, elected in 2020 to represent District 2, became the first openly LGBT person of color elected to the Berkeley City Council.

In 1973, Ying Lee became the first Asian American city councilmember in Berkeley.[127] Jenny Wong, elected in 2018, is the first Asian American City Auditor in Berkeley.

In 2014, the City of Berkeley passed a redistricting measure on the ballot[128] to create the nation's first student supermajority district in District 7, which in 2018 elected Rigel Robinson, a 22-year-old UC Berkeley graduate and the youngest Councilmember in the city's history.[129] While much of UC Berkeley's student housing is located in District 7, large dormitories also exist in Districts 6 and 8. Districts 4 and 7 are majority-student.

Nancy Skinner became the first student to serve on the City Council, elected in 1984 as a graduate student. Rigel Robinson, who was elected in 2018, became the second student to serve on the City Council as he completed his master's degree while in office.

Adena Ishii has become the first woman of color to be elected Mayor (mayor elect) of Berkley as of Tuesday, November 20, 2024.[citation needed]

The city's Public Health Division is one of four municipally-operated public health agencies in California (the other three being Long Beach, Pasadena, and Vernon). Though it is part of the city government, it qualifies for the same state funds as a county public health department.[130]

Berkeley is also part of Alameda County, for which the Government of Alameda County is defined and authorized under the California Constitution, California law, and the Charter of the County of Alameda.[131] The county government provides countywide services, such as elections and voter registration, law enforcement, jails, vital records, property records, tax collection, and social services. The county's health department does not cover the city. The county government is primarily composed of the elected five-member Board of Supervisors, other elected offices including the Sheriff/Coroner, the District Attorney, Assessor, Auditor-Controller/County Clerk/Recorder, and Treasurer/Tax Collector, and numerous county departments and entities under the supervision of the County Administrator.

In addition to the Berkeley Unified School District (which is coterminous with the city), Berkeley is also part of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART), the Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit), the East Bay Regional Park District, the East Bay Municipal Utility District, and the Peralta Community College District.[132]

Politics

editBerkeley has been a Democratic stronghold in presidential elections since 1960, becoming one of the most Democratic cities in the country. The last Republican presidential candidate to receive at least one-quarter of the vote in Berkeley was Richard Nixon in 1968. Consistent with Berkeley's reputation as a strongly liberal and/or progressive city, in the 2016 presidential election more votes were won by Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein than by Republican candidate Donald Trump.[133] In the 2020 Presidential election, Joe Biden received 93.8% of the vote while Donald Trump received 4.0% of the vote.[134]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of August 30, 2021, Berkeley has 75,390 registered voters. Of those, 56,740 (75.26%) are registered Democrats, 1,910 (2.53%) are registered Republicans, 14,106 (18.71%) have declined to state a political party affiliation, and 2,634 (3.49%) are registered with a third party.[135]

Berkeley became the first city in the United States to pass a sanctuary resolution on November 8, 1971.[136]

Media

editThe city had a daily newspaper, the Berkeley Gazette, which was founded c. 1877 and folded in 1984.[137] The Berkeley Barb published counter-culture news from 1965 to 1980. Current media include The Daily Californian, the student newspaper of UC Berkeley, the Berkeley Times, and local online-only publications Berkeleyside, the Berkeley Daily Planet, and The Berkeley Scanner.

Notable people

editNotable individuals who were born in and/or have lived in Berkeley include Kamala Harris, Steve Wozniak, scientists J. Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence, actors Ben Affleck, and Andy Samberg, Major League Baseball broadcaster Matt Vasgersian, model Rebecca Romijn, Billie Joe Armstrong, lead singer of Green Day, Adam Duritz of Counting Crows, rapper Lil B, authors Ursula K. Le Guin and Michael Chabon, entertainment and real estate mogul Herbie Herbert, and EDM producer KSHMR, and university presidents Blake R. Van Leer and Darryll Pines and adult education advocate Gretchen Bersch.[138]

Sister cities

editBerkeley has 17 sister cities:[139]

| Sister City | Year Established |

|---|---|

| Sakai, Osaka, Japan | 1966 |

| Edda people, Imo State, Nigeria | 1982 |

| San Antonio Los Ranchos, El Salvador | 1983 |

| Haidian District, Beijing, China | 1985 |

| Gao, Mali | 1985 |

| Mathopestad, South Africa | 1986 |

| León, Nicaragua | 1986 |

| Brits, South Africa | 1986 |

| Jena, Thuringia, Germany | 1989 |

| Yondó, Colombia | 1990 |

| Dmitrov, Russia | 1991 |

| Uma Bawang, Borneo, Malaysia[140] | 1991 |

| Ulan-Ude, Russia | 1992 (cancelled in 2022 due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine) |

| Yurok Tribe, California, United States | 1993 |

| Blackfeet Nation, Montana, United States | 2000 |

| Palma Soriano, Cuba | 2002 |

| Gongju, South Korea | 2018 |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Structure of Berkeley Government". City Clerk. City of Berkeley. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Elected Officials Home". City of Berkeley. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "Igor Tregub declares victory in Berkeley District 4 City Council race". Berkeleyside. June 4, 2024. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ "Cecilia Lunaparra sworn in as Berkeley's first Latina City Council member". Berkeleyside. April 30, 2024. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "Senators". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "California's 12th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Berkeley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Golla, Victor (2011). California Indian Languages. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-520-26667-4. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ "Mongoloid Type Skeleton is Dug Up at Berkeley". Oakland Tribune. June 20, 1925. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ Dinkelspiel, Frances (April 8, 2016). "Ohlone human remains found in trench in West Berkeley". Bekeleyside. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "The Spanish Myth". April 3, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ National Park Service. "Juan Bautista de Anza". Borrego Springs Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ^ Stadtman, Verne, ed. (1967). The Centennial Record of the University of California. Regents of the University of California. p. 114. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- ^ "George Berkeley – Biography". European Graduate School. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013.

- ^ Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 601. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ^ Berkeley Gazette. 1900 April 9

- ^ Berkeley 1900: Daily Life at the Turn of the Century, by Richard Schwartz. 2000. page 187

- ^ "Statutes of California, 1877–78, p. 888" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2016.

- ^ Schwartz, Richard. "The Chinese workers who fought discrimination at an 1880s West Berkeley soap factory". BerkeleySide. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ "Trip to Berkeley, California, Lcmp003 M3a29754". Library of Congress.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 72–105. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website. Archived April 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pettitt, George Albert (1973). Berkeley: the Town and Gown of it. Howell-North Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8310-7101-1.

- ^ "Downtown Berkeley Historic Resources Reconnaissance Survey" (PDF). City of Berkeley. August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Exactly Opposite the Golden Gate, edited by Phil McCardle, published 1983 by the Berkeley Historical Society, p.251

- ^ "Statutes of California, 1907-9, p.1208" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 4, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Hansen, Louis (March 1, 2021). "Is this the end of single-family zoning in the Bay Area? San Jose, Berkeley, other cities consider sweeping changes". San Jose Mercury News.

Single-family zoning, a form of exclusionary zoning, traces its roots in the U.S. to Berkeley in 1916, when city leaders sought to segregate white homeowners from apartment complexes rented by minority residents. It's become the default policy in cities and suburbs across the country.

- ^ Ruggiero, Angela (February 24, 2021). "Berkeley to end single-family residential zoning, citing racist ties". San Jose Mercury News.

Berkeley is thought to be the birthplace of single-family residential zoning; it began in the Elmwood neighborhood in 1916, where it forbade the construction of anything other than one home per lot. That has historically made it difficult for people of color or those with lower incomes to purchase or lease property in sought-after neighborhoods, city officials said. ... Even after racial discrimination such as redlining — refusing home loans to those in low-income neighborhoods — was outlawed, it continued in the form of single-family zoning, he said.

- ^ Baldassari, Erin; Solomon, Molly (October 5, 2020). "The Racist History of Single-Family Home Zoning". NPR. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020.

Where Did Single-Family Zoning Get Its Start? In none other than true-blue Berkeley, California. The progressive Bay Area enclave was the first city in the country to implement single-family zoning. It adopted the zoning rule for the Elmwood neighborhood in 1916, making it illegal to build anything other than one home on one lot in the neighborhood.

- ^ Metcalfe, John (February 17, 2021). "Berkeley may get rid of single-family zoning as a way to correct the arc of its ugly housing history". Berkeleyside.

- ^ "Berkeley, A City in History" Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Berkeley Public Library.

- ^ "California – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Shattuck Avenue: Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey". City of Berkeley. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Savidge, Nico (July 25, 2023). "Berkeley is adding new housing at the fastest rate in decades". Berkeleyside.

- ^ Mitchell, Don (1992). "Iconography and locational conflict from the underside: Free speech, People's Park, and the politics of homelessness in Berkeley, California". Political Geography. 11 (2): 152–169. doi:10.1016/0962-6298(92)90046-V.

- ^ City of Berkeley. "Urban Design and Preservation Element". Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "Ordinance: Rent Stabilization and Eviction for Good Cause - City of Berkeley, CA". Cityofberkeley.info. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ "What is Rent Control? ... and How Does It Affect Me?". City of Berkeley. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "Our History". Ecology Center. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Mark A. Stein (November 3, 1986). "Progressives in Berkeley Challenged by Tradition". L.A. Times. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Joe Garofoli (December 12, 2012). "Ethel Manheimer, Berkeley activist, dies". SFGate. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "Berkeley, CA Home Prices & Housing Information". AreaVibes. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Chloee Weiner (June 8, 2015). "South Berkeley residents mobilize around plan to develop Adeline Street corridor". Daily Cal. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "School Colors". Frontline. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ "International Student Enrollment Data". UC Berkeley. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Richard Brenneman (April 6, 2007). "Panoramic Sells Off 7 Apartment Buildings". Berkeley Daily Planet. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "Berkeley becomes first US city to declare Bisexual Pride Day, support 'marginalized' group". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 19, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Lovett, Ian (September 3, 2014). "Berkeley Pushes a Boundary on Medical Marijuana". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ "How Did Berkeley Pass A Soda Tax? Bloomberg's Cash Didn't Hurt". NPR. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015.

- ^ Emilie Raguso (June 11, 2015). "Police report mistakes, challenges in Berkeley protests". Berkeleyside. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Emilie Raguso (June 11, 2015). "BPD chief: Lessons learned in 2014 'Black Lives Matter' protests guided us during Milo demonstrations". Berkeleyside. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ James Queally; Paige St John; Benjamin Oreskes; David Zahniser (August 28, 2017). "Violence by far-left protesters in Berkeley sparks alarm". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ "Heavy Police Presence Keeps Berkeley Coulter Protests Peaceful". April 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "People's Park protesters arrested by UC Berkeley police before removal of trees". The Mercury News. January 15, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.