In quantum electrodynamics , Bhabha scattering is the electron -positron scattering process:

e

+

e

−

→

e

+

e

−

{\displaystyle e^{+}e^{-}\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-}}

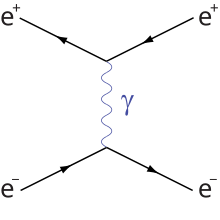

There are two leading-order Feynman diagrams contributing to this interaction: an annihilation process and a scattering process. Bhabha scattering is named after the Indian physicist Homi J. Bhabha .

The Bhabha scattering rate is used as a luminosity monitor in electron-positron colliders.

Differential cross section

edit

To leading order , the spin-averaged differential cross section for this process is

d

σ

d

(

cos

θ

)

=

π

α

2

s

(

u

2

(

1

s

+

1

t

)

2

+

(

t

s

)

2

+

(

s

t

)

2

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} \sigma }{\mathrm {d} (\cos \theta )}}={\frac {\pi \alpha ^{2}}{s}}\left(u^{2}\left({\frac {1}{s}}+{\frac {1}{t}}\right)^{2}+\left({\frac {t}{s}}\right)^{2}+\left({\frac {s}{t}}\right)^{2}\right)\,}

where s ,t , and u are the Mandelstam variables ,

α

{\displaystyle \alpha }

fine-structure constant , and

θ

{\displaystyle \theta }

This cross section is calculated neglecting the electron mass relative to the collision energy and including only the contribution from photon exchange. This is a valid approximation at collision energies small compared to the mass scale of the Z boson , about 91 GeV; at higher energies the contribution from Z boson exchange also becomes important.

Mandelstam variables

edit

In this article, the Mandelstam variables are defined by

s

=

{\displaystyle s=\,}

(

k

+

p

)

2

=

{\displaystyle (k+p)^{2}=\,}

(

k

′

+

p

′

)

2

≈

{\displaystyle (k'+p')^{2}\approx \,}

2

k

⋅

p

≈

{\displaystyle 2k\cdot p\approx \,}

2

k

′

⋅

p

′

{\displaystyle 2k'\cdot p'\,}

t

=

{\displaystyle t=\,}

(

k

−

k

′

)

2

=

{\displaystyle (k-k')^{2}=\,}

(

p

−

p

′

)

2

≈

{\displaystyle (p-p')^{2}\approx \,}

−

2

k

⋅

k

′

≈

{\displaystyle -2k\cdot k'\approx \,}

−

2

p

⋅

p

′

{\displaystyle -2p\cdot p'\,}

u

=

{\displaystyle u=\,}

(

k

−

p

′

)

2

=

{\displaystyle (k-p')^{2}=\,}

(

p

−

k

′

)

2

≈

{\displaystyle (p-k')^{2}\approx \,}

−

2

k

⋅

p

′

≈

{\displaystyle -2k\cdot p'\approx \,}

−

2

k

′

⋅

p

{\displaystyle -2k'\cdot p\,}

where the approximations are for the high-energy (relativistic) limit.

Deriving unpolarized cross section

edit

Both the scattering and annihilation diagrams contribute to the transition matrix element. By letting k and k' represent the four-momentum of the positron, while letting p and p' represent the four-momentum of the electron, and by using Feynman rules one can show the following diagrams give these matrix elements:

Where we use:

γ

μ

{\displaystyle \gamma ^{\mu }\,}

Gamma matrices ,

u

,

a

n

d

u

¯

{\displaystyle u,\ \mathrm {and} \ {\bar {u}}\,}

v

,

a

n

d

v

¯

{\displaystyle v,\ \mathrm {and} \ {\bar {v}}\,}

Four spinors ).

(scattering)

(annihilation)

M

=

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {M}}=\,}

−

e

2

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

1

(

k

−

k

′

)

2

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

{\displaystyle -e^{2}\left({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'}\right){\frac {1}{(k-k')^{2}}}\left({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p}\right)}

+

e

2

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

u

p

)

1

(

k

+

p

)

2

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

{\displaystyle +e^{2}\left({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }u_{p}\right){\frac {1}{(k+p)^{2}}}\left({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }v_{k'}\right)}

Notice that there is a relative sign difference between the two diagrams.

Square of matrix element

edit

To calculate the unpolarized cross section , one must average over the spins of the incoming particles (s e- and s e+ possible values) and sum over the spins of the outgoing particles. That is,

|

M

|

2

¯

{\displaystyle {\overline {|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}}}\,}

=

1

(

2

s

e

−

+

1

)

(

2

s

e

+

+

1

)

∑

s

p

i

n

s

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{(2s_{e-}+1)(2s_{e+}+1)}}\sum _{\mathrm {spins} }|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

=

1

4

∑

s

=

1

2

∑

s

′

=

1

2

∑

r

=

1

2

∑

r

′

=

1

2

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{4}}\sum _{s=1}^{2}\sum _{s'=1}^{2}\sum _{r=1}^{2}\sum _{r'=1}^{2}|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

First, calculate

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle |{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle |{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

e

4

|

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

(

k

−

k

′

)

2

|

2

{\displaystyle e^{4}\left|{\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p})}{(k-k')^{2}}}\right|^{2}\,}

(scattering)

−

e

4

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

(

k

−

k

′

)

2

)

∗

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

u

p

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

k

+

p

)

2

)

{\displaystyle {}-e^{4}\left({\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p})}{(k-k')^{2}}}\right)^{*}\left({\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }u_{p})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }v_{k'})}{(k+p)^{2}}}\right)\,}

(interference)

−

e

4

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

(

k

−

k

′

)

2

)

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

u

p

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

k

+

p

)

2

)

∗

{\displaystyle {}-e^{4}\left({\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p})}{(k-k')^{2}}}\right)\left({\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }u_{p})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }v_{k'})}{(k+p)^{2}}}\right)^{*}\,}

(interference)

+

e

4

|

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

u

p

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

k

+

p

)

2

|

2

{\displaystyle {}+e^{4}\left|{\frac {({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }u_{p})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }v_{k'})}{(k+p)^{2}}}\right|^{2}\,}

(annihilation)

edit

Magnitude squared of M

edit

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle |{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

)

∗

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

u

p

)

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}{\Big (}({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p}){\Big )}^{*}{\Big (}({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }u_{p}){\Big )}\,}

(

1

)

{\displaystyle (1)\,}

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

μ

v

k

′

)

∗

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

μ

u

p

)

∗

)

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

u

p

)

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}{\Big (}({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k'})^{*}({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p})^{*}{\Big )}{\Big (}({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }v_{k'})({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }u_{p}){\Big )}\,}

(

2

)

{\displaystyle (2)\,}

(complex conjugate will flip order)

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

(

v

¯

k

′

γ

μ

v

k

)

(

u

¯

p

γ

μ

u

p

′

)

)

(

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

u

p

)

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}{\Big (}\left({\bar {v}}_{k'}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k}\right)\left({\bar {u}}_{p}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p'}\right){\Big )}{\Big (}\left({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }v_{k'}\right)\left({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }u_{p}\right){\Big )}\,}

(

3

)

{\displaystyle (3)\,}

(move terms that depend on same momentum to be next to each other)

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

v

¯

k

′

γ

μ

v

k

)

(

v

¯

k

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

u

¯

p

γ

μ

u

p

′

)

(

u

¯

p

′

γ

ν

u

p

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\left({\bar {v}}_{k'}\gamma ^{\mu }v_{k}\right)\left({\bar {v}}_{k}\gamma ^{\nu }v_{k'}\right)\left({\bar {u}}_{p}\gamma _{\mu }u_{p'}\right)\left({\bar {u}}_{p'}\gamma _{\nu }u_{p}\right)\,}

(

4

)

{\displaystyle (4)\,}

Next, we'd like to sum over spins of all four particles. Let s and s' be the spin of the electron and r and r' be the spin of the positron.

∑

s

p

i

n

s

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle \sum _{\mathrm {spins} }|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

∑

r

′

v

¯

k

′

γ

μ

(

∑

r

v

k

v

¯

k

)

γ

ν

v

k

′

)

(

∑

s

u

¯

p

γ

μ

(

∑

s

′

u

p

′

u

¯

p

′

)

γ

ν

u

p

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\left(\sum _{r'}{\bar {v}}_{k'}\gamma ^{\mu }(\sum _{r}v_{k}{\bar {v}}_{k})\gamma ^{\nu }v_{k'}\right)\left(\sum _{s}{\bar {u}}_{p}\gamma _{\mu }(\sum _{s'}{u_{p'}{\bar {u}}_{p'}})\gamma _{\nu }u_{p}\right)\,}

(

5

)

{\displaystyle (5)\,}

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

Tr

(

(

∑

r

′

v

k

′

v

¯

k

′

)

γ

μ

(

∑

r

v

k

v

¯

k

)

γ

ν

)

Tr

(

(

∑

s

u

p

u

¯

p

)

γ

μ

(

∑

s

′

u

p

′

u

¯

p

′

)

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\operatorname {Tr} \left({\Big (}\sum _{r'}v_{k'}{\bar {v}}_{k'}{\Big )}\gamma ^{\mu }{\Big (}\sum _{r}v_{k}{\bar {v}}_{k}{\Big )}\gamma ^{\nu }\right)\operatorname {Tr} \left({\Big (}\sum _{s}u_{p}{\bar {u}}_{p}{\Big )}\gamma _{\mu }{\Big (}\sum _{s'}{u_{p'}{\bar {u}}_{p'}}{\Big )}\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

(

6

)

{\displaystyle (6)\,}

(now use Completeness relations )

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

Tr

(

(

k

/

′

−

m

)

γ

μ

(

k

/

−

m

)

γ

ν

)

⋅

Tr

(

(

p

/

′

+

m

)

γ

μ

(

p

/

+

m

)

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\operatorname {Tr} \left((k\!\!\!/'-m)\gamma ^{\mu }(k\!\!\!/-m)\gamma ^{\nu }\right)\cdot \operatorname {Tr} \left((p\!\!\!/'+m)\gamma _{\mu }(p\!\!\!/+m)\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

(

7

)

{\displaystyle (7)\,}

(now use Trace identities )

=

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

4

(

k

′

μ

k

ν

−

(

k

′

⋅

k

)

η

μ

ν

+

k

′

ν

k

μ

)

+

4

m

2

η

μ

ν

)

(

4

(

p

′

μ

p

ν

−

(

p

′

⋅

p

)

η

μ

ν

+

p

ν

′

p

μ

)

+

4

m

2

η

μ

ν

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {e^{4}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\left(4\left({k'}^{\mu }k^{\nu }-(k'\cdot k)\eta ^{\mu \nu }+k'^{\nu }k^{\mu }\right)+4m^{2}\eta ^{\mu \nu }\right)\left(4\left({p'}_{\mu }p_{\nu }-(p'\cdot p)\eta _{\mu \nu }+p'_{\nu }p_{\mu }\right)+4m^{2}\eta _{\mu \nu }\right)\,}

(

8

)

{\displaystyle (8)\,}

=

32

e

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

(

k

′

⋅

p

′

)

(

k

⋅

p

)

+

(

k

′

⋅

p

)

(

k

⋅

p

′

)

−

m

2

p

′

⋅

p

−

m

2

k

′

⋅

k

+

2

m

4

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {32{e^{4}}}{(k-k')^{4}}}\left((k'\cdot p')(k\cdot p)+(k'\cdot p)(k\cdot p')-m^{2}p'\cdot p-m^{2}k'\cdot k+2m^{4}\right)\,}

(

9

)

{\displaystyle (9)\,}

Now that is the exact form, in the case of electrons one is usually interested in energy scales that far exceed the electron mass. Neglecting the electron mass yields the simplified form:

1

4

∑

s

p

i

n

s

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{4}}\sum _{\mathrm {spins} }|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

=

32

e

4

4

(

k

−

k

′

)

4

(

(

k

′

⋅

p

′

)

(

k

⋅

p

)

+

(

k

′

⋅

p

)

(

k

⋅

p

′

)

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {32e^{4}}{4(k-k')^{4}}}\left((k'\cdot p')(k\cdot p)+(k'\cdot p)(k\cdot p')\right)\,}

(use the Mandelstam variables in this relativistic limit)

=

8

e

4

t

2

(

1

2

s

1

2

s

+

1

2

u

1

2

u

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {8e^{4}}{t^{2}}}\left({\tfrac {1}{2}}s{\tfrac {1}{2}}s+{\tfrac {1}{2}}u{\tfrac {1}{2}}u\right)\,}

=

2

e

4

s

2

+

u

2

t

2

{\displaystyle =2e^{4}{\frac {s^{2}+u^{2}}{t^{2}}}\,}

edit

The process for finding the annihilation term is similar to the above. Since the two diagrams are related by crossing symmetry , and the initial and final state particles are the same, it is sufficient to permute the momenta, yielding

1

4

∑

s

p

i

n

s

|

M

|

2

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{4}}\sum _{\mathrm {spins} }|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}\,}

=

32

e

4

4

(

k

+

p

)

4

(

(

k

⋅

k

′

)

(

p

⋅

p

′

)

+

(

k

′

⋅

p

)

(

k

⋅

p

′

)

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {32e^{4}}{4(k+p)^{4}}}\left((k\cdot k')(p\cdot p')+(k'\cdot p)(k\cdot p')\right)\,}

=

8

e

4

s

2

(

1

2

t

1

2

t

+

1

2

u

1

2

u

)

{\displaystyle ={\frac {8e^{4}}{s^{2}}}\left({\tfrac {1}{2}}t{\tfrac {1}{2}}t+{\tfrac {1}{2}}u{\tfrac {1}{2}}u\right)\,}

=

2

e

4

t

2

+

u

2

s

2

{\displaystyle =2e^{4}{\frac {t^{2}+u^{2}}{s^{2}}}\,}

(This is proportional to

(

1

+

cos

2

θ

)

{\displaystyle (1+\cos ^{2}\theta )}

θ

{\displaystyle \theta }

Evaluating the interference term along the same lines and adding the three terms yields the final result

|

M

|

2

¯

2

e

4

=

u

2

+

s

2

t

2

+

2

u

2

s

t

+

u

2

+

t

2

s

2

{\displaystyle {\frac {\overline {|{\mathcal {M}}|^{2}}}{2e^{4}}}={\frac {u^{2}+s^{2}}{t^{2}}}+{\frac {2u^{2}}{st}}+{\frac {u^{2}+t^{2}}{s^{2}}}\,}

Completeness relations

edit

The completeness relations for the four-spinors u and v are

∑

s

=

1

,

2

u

p

(

s

)

u

¯

p

(

s

)

=

p

/

+

m

{\displaystyle \sum _{s=1,2}{u_{p}^{(s)}{\bar {u}}_{p}^{(s)}}=p\!\!\!/+m\,}

∑

s

=

1

,

2

v

p

(

s

)

v

¯

p

(

s

)

=

p

/

−

m

{\displaystyle \sum _{s=1,2}{v_{p}^{(s)}{\bar {v}}_{p}^{(s)}}=p\!\!\!/-m\,}

where

p

/

=

γ

μ

p

μ

{\displaystyle p\!\!\!/=\gamma ^{\mu }p_{\mu }\,}

Feynman slash notation )

u

¯

=

u

†

γ

0

{\displaystyle {\bar {u}}=u^{\dagger }\gamma ^{0}\,}

To simplify the trace of the Dirac gamma matrices , one must use trace identities. Three used in this article are:

The Trace of any product of an odd number of

γ

μ

{\displaystyle \gamma _{\mu }\,}

Tr

(

γ

μ

γ

ν

)

=

4

η

μ

ν

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Tr} (\gamma ^{\mu }\gamma ^{\nu })=4\eta ^{\mu \nu }}

Tr

(

γ

ρ

γ

μ

γ

σ

γ

ν

)

=

4

(

η

ρ

μ

η

σ

ν

−

η

ρ

σ

η

μ

ν

+

η

ρ

ν

η

μ

σ

)

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Tr} \left(\gamma _{\rho }\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\sigma }\gamma _{\nu }\right)=4\left(\eta _{\rho \mu }\eta _{\sigma \nu }-\eta _{\rho \sigma }\eta _{\mu \nu }+\eta _{\rho \nu }\eta _{\mu \sigma }\right)\,}

Using these two one finds that, for example,

Tr

(

(

p

/

′

+

m

)

γ

μ

(

p

/

+

m

)

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Tr} \left((p\!\!\!/'+m)\gamma _{\mu }(p\!\!\!/+m)\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

=

Tr

(

p

/

′

γ

μ

p

/

γ

ν

)

+

Tr

(

m

γ

μ

p

/

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle =\operatorname {Tr} \left(p\!\!\!/'\gamma _{\mu }p\!\!\!/\gamma _{\nu }\right)+\operatorname {Tr} \left(m\gamma _{\mu }p\!\!\!/\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

+

Tr

(

p

/

′

γ

μ

m

γ

ν

)

+

Tr

(

m

2

γ

μ

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle +\operatorname {Tr} \left(p\!\!\!/'\gamma _{\mu }m\gamma _{\nu }\right)+\operatorname {Tr} \left(m^{2}\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

(the two middle terms are zero because of (1))

=

Tr

(

p

/

′

γ

μ

p

/

γ

ν

)

+

m

2

Tr

(

γ

μ

γ

ν

)

{\displaystyle =\operatorname {Tr} \left(p\!\!\!/'\gamma _{\mu }p\!\!\!/\gamma _{\nu }\right)+m^{2}\operatorname {Tr} \left(\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }\right)\,}

(use identity (2) for the term on the right)

=

p

′

ρ

p

σ

Tr

(

γ

ρ

γ

μ

γ

σ

γ

ν

)

+

m

2

⋅

4

η

μ

ν

{\displaystyle ={p'}^{\rho }p^{\sigma }\operatorname {Tr} \left(\gamma _{\rho }\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\sigma }\gamma _{\nu }\right)+m^{2}\cdot 4\eta _{\mu \nu }\,}

(now use identity (3) for the term on the left)

=

p

′

ρ

p

σ

4

(

η

ρ

μ

η

σ

ν

−

η

ρ

σ

η

μ

ν

+

η

ρ

ν

η

μ

σ

)

+

4

m

2

η

μ

ν

{\displaystyle ={p'}^{\rho }p^{\sigma }4\left(\eta _{\rho \mu }\eta _{\sigma \nu }-\eta _{\rho \sigma }\eta _{\mu \nu }+\eta _{\rho \nu }\eta _{\mu \sigma }\right)+4m^{2}\eta _{\mu \nu }\,}

=

4

(

p

′

μ

p

ν

−

(

p

′

⋅

p

)

η

μ

ν

+

p

ν

′

p

μ

)

+

4

m

2

η

μ

ν

{\displaystyle =4\left({p'}_{\mu }p_{\nu }-(p'\cdot p)\eta _{\mu \nu }+p'_{\nu }p_{\mu }\right)+4m^{2}\eta _{\mu \nu }\,}

Bhabha scattering has been used as a luminosity monitor in a number of e+ e− collider physics experiments. The accurate measurement of luminosity is necessary for accurate measurements of cross sections.

Small-angle Bhabha scattering was used to measure the luminosity of the 1993 run of the Stanford Large Detector (SLD), with a relative uncertainty of less than 0.5%.[ 1]

Electron-positron colliders operating in the region of the low-lying hadronic resonances (about 1 GeV to 10 GeV), such as the Beijing Electron–Positron Collider II and the Belle and BaBar "B-factory" experiments, use large-angle Bhabha scattering as a luminosity monitor. To achieve the desired precision at the 0.1% level, the experimental measurements must be compared to a theoretical calculation including next-to-leading-order radiative corrections .[ 2] anomalous magnetic dipole moment of the muon , which is used to constrain supersymmetry and other models of physics beyond the Standard Model .