The Binet-Simon Intelligence Test was the first intelligence test that could be used to predict scholarly performance and which was widely accepted by the fields of psychology and psychiatry.[2][3][4] The development of the test started in 1905 with Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon in Paris, France.[3][4] Binet and Simon published articles about the test multiple times in Binet's scientific journal L'Année Psychologique, twice in 1905, once in 1908, and once in 1911 (this time, Binet was the sole author).[5] The revisions and publications on the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test by Binet and Simon stopped in 1911 due to the death of Alfred Binet in 1911.[3]

The outcomes of the test were related to academic performance.[3] The Binet-Simon was popular because psychologists and psychiatrists at the time felt that the test was able to measure higher and more complex mental functions in situations that closely resembled real life.[3] This was in contrast to previous attempts at tests of intelligence, which were designed to measure specific and separate "faculties" of the mind.[2]

Binet's and Simon's intelligence test was well received among contemporary psychologists because it fit the generally accepted view that intelligence includes many different mental functions (e.g. language proficiency, imagination, memory, sensory discrimination).[3]

Precursors

editThe precursors to the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test were craniological and anthropometric research, especially the anthropometric research by Francis Galton and James Mckeen Cattell.[2][3][6] Galton and Cattell discontinued their research when they realised that their measurements of human bodies did not correlate to academic performance.[3] As a result, French psychology excluded methods that measured intelligence based on correlations between physical measurements of the body and academic success.[6]

Development

editBefore working on the test, Alfred Binet had experience of raising his two daughters on whom he also conducted studies of intelligence between 1900 and 1902.[3][4] He had already written a considerable number of scientific articles on individual differences, intelligence, magnetism, hypnosis, and many other psychological topics.[3]

Théodore Simon had studied medicine and was beginning his PhD at the Perray-Vacluse psychiatric hospital when he contacted Binet in 1898, when Simon was 25 years old.[5] Simon's supervisor, Dr Blin, tasked Simon with finding a better assessment to measure children's intelligence than the available medical methods. Binet and Simon started working together, first looking at the relationship between skull measurements and intelligence, and later abandoning this anthropometric approach in favour of psychological testing.[2][5]

The development of Binet and Simon's intelligence test started in Paris in 1905.[3][4][5] The test was issued to identify mental abnormality in French primary school children. These children, referred to as feebleminded or mentally retarded, supposedly caused trouble in French primary schools because they were unable to follow standard education and were disturbing the rest of their classmates.[3][4] The law on compulsory primary education for children ages of six to thirteen was passed in 1882, and in 1904, primary school teachers started complaining about children of abnormal intelligence in the press and meetings.[4]

These complaints were picked up by French national politicians, resulting in the establishment of the Bourgeois Commission in 1904 by the French Minister of Public Instruction. This Commission aimed to study the measures to be taken so that these abnormal children could be identified.[3][4] The Bourgeois Commission was staffed by specialists in the study of children with mental abnormality (psychiatrists, psychologists), members of the public education system and representatives from the interior ministry.[4] Binet joined the Commission because of his presidency of La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant (Free Society of the Psychological Study of the Child). La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant was a scientific collaboration mainly between scientists and educators.[4][3][7][8] Binet volunteered as the Secretary of the Commission.

Binet constructed the first intelligence test to limit the influence of psychiatrists. Psychiatrists such as Bourneville (who was also on the Bourgeois Commission) argued for taking abnormal children out of schools and placing them in medical asylums to receive special education from medical practitioners.[4] Identifying and treating the abnormal had, until that point, been a psychiatric domain but Binet wanted to keep these children in schools and looked for a way for psychologists to become the authority.[4] Binet was supported in this attempt by La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant, other collaborators and friends.[4]

Despite Binet's position as Secretary of the Bourgeois Commission, he was unable to prevent the Commission from recommending that only medical and educational experts should decide on the intellectual level of children and if they should go to a special school.[9][4] However, the recommendation never turned into legislation, nor did Bourneville's plans for creating special education classes in asylums. La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant lobbied against both these plans, and Binet was encouraged to come up with a better alternative to measure the difference between normal and abnormal children.[4][5]

Versions

editThere have been three versions of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test. The first, designed in 1905, was designed to detect abnormal children. The second version, in 1908, added the notion of age, making it possible to calculate how many years a child was intellectually behind. The last test, from 1911, retained the notion of mental age and was a revised version of the 1908 version. The tests from 1908 and 1911 were later used by American psychologists, such as Henry H. Goddard and Lewis Terman.[10]

1905 version

editThe 1905 version aimed to distinguish children with normal and 'abnormal' intelligence. Binet and Simon grouped children into: 'idiocy', 'imbecility' 'debility' and 'normality'.[4] Each category had its own set of tasks, organised from lowest to highest difficulty.[2][4] Typically, the administration of the full test only took fifteen minutes.[4]

Binet and Simon assumed that an 'idiot' had basic skills. Six subtests on the 1905 test first measured these basic skills. The second part of the Binet-Simon Intelligence test aimed to differentiate between 'idiocy' and 'imbecility'. If a child could not pass all the subtests in this section, the test was discontinued, and the child was labelled an 'idiot'. This part was made up of five subtests.[4] The third part of the 1905 test intended to differentiate between imbecility and debility. If a child could not pass all the tests from this part, they were labelled an imbecile. This part included 15 subtests. The fourth and final part of the test distinguished between debility and normality. This part had four subtests.[4]

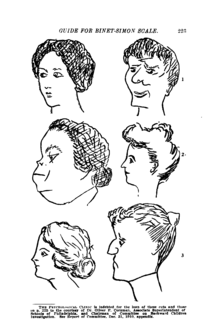

The measurement of basic skills included tasks such as object grabbing and testing knowledge of food. The distinction between idiocy and imbecility was made by for example testing verbal knowledge of objects and images and comparing two lines of different lengths. To differentiate between an imbecility and debility, some of the tasks that were used were drawing from memory and repetition of numbers. Lastly, to differentiate between debility and normality, a child could be asked to respond to an abstract question or to perform a paper cutting exercise.[4] For a full overview of all the subtests of the 1905 version, see the two images on the right.

The 1905 test was mainly based on Binet's work from the previous 15 years and was constructed within a few weeks.[4] This bundle of tests was the first metric scale of intelligence ("échelle métrique de l'intelligence").[5]

1908 version

editThe 1908 version was the first version of the test to include scaling to assess mental age.[3] The published text could be easily read as a manual of an intelligence test.[5] The test had become a scale, and the subtests were arranged from easiest to most difficult. The test also showed in detail the four to eight tasks that children should be able to perform at 11 different ages, ranging from 3 to 13.[3][5] The test was constructed by giving the subtests to children of a specific (chronological) age group. If 75% of these children passed, the subtest would be assigned to that age group.[3][9]

The test measured what Binet termed mental age, the age level at which a child could perform. If a child, for example, could perform all the tasks meant for a 10-year-old, but not those meant for an 11-year-old, they would have the mental age of a 10. The mental age was established independently from the chronological age, meaning that a child could have the mental age of a 10-year-old and the chronological age of a 12-year-old. It was also possible for a child to have a higher mental age than their chronological age.[3] If the mental age of a child was two years behind their chronological age, the child was classified as abnormal. Binet and Simon saw a two or more years lag as a warning sign of low intelligence, which required special attention, first by providing remedial education.[5]

The 1908 version of the Binet-Simon test was seen as a scientific and objective method capable of delivering factual statements about the complex mental phenomenon of human intellectual capabilities.[3][6]

1911 version

editIn 1911, Binet revised the 1908 version without Simon.[3][5] Simon did not contribute to the 1911 version because he had moved to Northern France to work at the Saint-Yon asylum and on his book "L'Aliéné, l'Asile, l'Infirmier" [The Alienated, the Asylum, the Nurse].[5] In the 1911 version, no new tests were added. The number of subtests was evened out, with five tasks per age group. Binet created new categories for 15-year-olds and adults by moving the most difficult subtests to these new categories.[5] This 1911 publication was made up mainly of clarifications and reactions to comments from teachers and researchers and the presentation of new data collected from using the test in a couple of schools.[5] Binet died in 1911, and Simon did not work on any new test versions.[5]

Translated version for the United States 1911

editthis English version included a category for idiocy (questions 1-6), which measures a mental age of 1-2, and the addition of tests 17a and 50a.[1] It also focused on distinguishing between different levels of mental ability. Arranged from lowest to highest, these were: 'idiot', 'imbecile', 'moron' and 'normal'.[1]

The test was advised to be administered in the following ways. Before starting the test, the person conducting the test, the experimenter, would note down the biodata of the subject. These biodata were: name, birth year, place of birth, nationality, sex, health, physical defects, school grade, school standing (years pedagogically retarded or accelerated) and the data of the examination and who the experimenter was that executed the test.[1]

After the test was finished, the experimenter indicated the subject's mental condition during the test. The general results were first reported as the number of 'passed tests of mental age', then the chronological (actual) age, and then the number of years difference between this and intellectual age.

Lastly, the experimenter had to indicate the degree of mentality. The labels an examiner could choose were 'supernormal', 'normal', 'subnormal', 'backward' or 'feeble-minded'. These labels could also be linked to the labels 'low, middle or high idiot'; low, middle or high imbecile, and low, middle or high moron.[1]

Validity

editWhen the test was published in France, its validity was accepted because it could distinguish between normal and intellectually slow children and because the scores on the test increased with a child's age.[11] Moreover, Binet and Simon presented evidence that the order of tasks was linear and that a child's score on the test would correlate to their academic performance.[5]

In the United States, Henry Goddard (1886-1957) was enthralled by the Binet-Simon Test's efficiency. he is quoted as saying: 'No one can use the tests on any fair number of children without becoming convinced that whatever defects or faults they may have, and no one can claim that they are perfect, the tests do come amazingly near [to] what we feel to be the truth in regard to the mental status of any child tested.'[3]

Who used it?

editThe test's original purpose was to distinguish between normal and abnormal children in French primary schools. The test was administered by French public school teachers.[8]

Critiques

editYerkes's Critique

editRobert Yerkes (1876-1956) critized the Binet-Simon test for assuming that everyone taking it is a native speaker. He also argued that an intelligence test should have a univerisal performance scale, not an age-graded scale. He further stated that social and biological differences should be considered when deciding the norms used to evaluate performance .[10]

Gould's Critique

editIn Stephen Jay Gould's book 'the mismeasure of man', Gould argues that even though the Binet-Simon test was used for a morally good goal (to identify children who needed extra help), the way the test was subsequently used in the United States by psychologists such as Spearman, Terman, Goddard, Burt and Brigham, was not ethical. Gould argues that in the United States, the intelligence test was used to help discriminate against foreigners and members of the working class and to help those of higher social classes.[2][3]

Mülberger's Critique

editMülberger (2020) has pointed out that an intelligence test is a theory-laden tool that 'does something' with those who interact with it. The Binet-Simon Intelligence Test instrumentalized intelligence for psychologists for the first time. Consequently, ontological assumptions and conceptual understandings were black-boxed. As a result, the concept of intelligence became what the test was measuring.[3] The test has built-in sets of norms and values that assume the kind of mental work a normal citizen should be able to perform. Mülberger (2020) recognizes the methodological diligence of psychologists to assess and assure its validity, reliability and replicability and, at the same time, the test could be damaging to the tested and had the ability to bring about scepticism and fear.[3]

Influence

editThe Binet-Simon intelligence test was the model for future intelligence tests.[11] Many later intelligence tests also combined different mental tests to arrive at a single score of intelligence.[11] Specific items from the Binet-Simon test were also be re-used for other intelligence tests.[11]

Theodore Simon was the biggest supporter of the test after Binet's passing in 1911, advocating for its international use. Shortly after, other famous pedagogues and psychologists such as Édouard Claparède and Ovide Decroly, joined him in his advocacy of the test.[3][9] By using their large and far-reaching network, information about the Binet-Simon test's reliability and efficiency spread rapidly during the period when schooling became public and graded.[3]

A group of physicians from Barcelona hired by the City Hall were among the first to use a translated version of the 1908 version.They tested 420 boys and girls to identify physically, mentally, and socially lagging schoolchildren. Parents and children hoped for low scores on the test because it would mean the children would be chosen to go to state-sponsored summer camps in the countryside.[3]

Henry H. Goddard became aware of the Binet-Simon test while travelling through Europe, and became the greatest promoter of the Binet-Simon Intelligence test in the United States.[9][11] In 1916, Goddard instructed his laboratory field worker, Elizabeth S. Kite, to translate the complete Binet and Simon's work on the intelligence test into English.[9] As the head of research at Vineland Training School for Feeble-minded Girls and Boys, Goddard led a movement that would result in the widespread use of the Binet-Simon test in American Institutions.[9][11]

William Stern's Intelligence Quotient (1912)

editIn 1912, William Stern (1871-1938) standardized the test scores of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test. He achieved this by dividing the mental age by the chronological age. The number this calculation produced was the widely known intelligence quotient or IQ. For many people, both testers and tested, this number became a person's precise built-in intelligence.[3] Théodore Simon critcized this revision of the Binet-Simon test, arguing it to be a betrayal of the test's objective.[9]

Robbert Yerkes & James Bridges (1915)

editRobbert Yerkes and James Bridges revised the year scale of the Binet-Simon test to a point scale, becoming the Yerkes-Bridges Point Scale Examination. Yerkes and Bridges achieved this by groupings items of similar content. For example, the Binet-Simon had multiple memory span digit tests spread over different age groups.For example, Yerkes and Bridges took all those memory span digit tests and created a new category for them, arranged from easiest to difficult. They created many other groups using this technique. This adaptation would become the model for the later Wechsler Scales.[11]

Lewis Terman's Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (1916)

editThe Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales was a revised version of the Binet-Simon Intelligence test by Lewis Terman. He started his revision in 1910 and published it in 1916.[9] Terman used the 1908 version of the Binet-Simon test for his revision.[9] The most important addition is the replacement of mental age for the intelligence quotient (IQ). The Stanford-Binet Intelligence test also gained items. The first version of the Stanford-Binet had 90 items, and a later revised version had 129.[3]

See Also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Wallin, J. E. Wallace (15 December 1911). "A Practical Guide for the Administration of the Binet-Simon Scale for Measuring Intelligence". The Psychological Clinic. 5 (7): 217–238. PMC 5147539. PMID 28909840.

- ^ a b c d e f Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The mismeasure of man. New York: Norton. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-393-01489-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Mülberger, Annette (2020-11-19), "Biographies of a Scientific Subject: The Intelligence Test", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.694, ISBN 978-0-19-023655-7, retrieved 2024-06-20

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Nicolas, Serge; Andrieu, Bernard; Croizet, Jean-Claude; Sanitioso, Rasyid B.; Burman, Jeremy Trevelyan (September 2013). "Sick? Or slow? On the origins of intelligence as a psychological object". Intelligence. 41 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.08.006. ISSN 0160-2896.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Brysbaert, Marc; Nicolas, Serge (2024-05-16). "Two Persistent Myths About Binet and the Beginnings of Intelligence Tests in Psychology Textbooks". Collabra: Psychology. 10 (1). doi:10.1525/collabra.117600. ISSN 2474-7394.

- ^ a b c Cicciola, Elisabetta; Foschi, Renato; Lombardo, Giovanni Pietro (August 2014). "Making up intelligence scales: De Sanctis's and Binet's tests, 1905 and after". History of Psychology. 17 (3): 223–236. doi:10.1037/a0033740. ISSN 1939-0610. PMID 24127867.

- ^ Foschi, Renato; Cicciola, Elisabetta (2006). "Politics and naturalism in the 20th century psychology of Alfred Binet". History of Psychology. 9 (4): 267–289. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.9.4.267. ISSN 1939-0610.

- ^ a b Zenderland, Leila (April 1988). "Education, evangelism, and the origins of clinical psychology: The child-study legacy". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 24 (2): 152–165. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(198804)24:2<152::AID-JHBS2300240203>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 3286752.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Flanagan, Dawn P.; McDonough, Erin M.; Kaufman, Alan S., eds. (2018). Contemporary intellectual assessment: theories, tests, and issues (4th ed.). New York London: The Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-3578-1.

- ^ a b Sokal, Michael M.; American Association for the Advancement of Science, eds. (1987). Psychological testing and American society, 1890-1930. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1193-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Boake, Corwin (May 2002). "From the Binet–Simon to the Wechsler–Bellevue: Tracing the History of Intelligence Testing". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 24 (3): 383–405. doi:10.1076/jcen.24.3.383.981. ISSN 1380-3395. PMID 11992219.

Further reading

edit- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Th. (1916), "Application of the new methods to the diagnosis of the intellectual level among normal and subnormal children in institutions and in the primary schools (L'Année Psych., 1905, pp. 245-336).", The development of intelligence in children (The Binet-Simon Scale)., Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co, pp. 91–181, doi:10.1037/11069-003, retrieved 2024-06-25

- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Theophile (1961), Jenkins, James J.; Paterson, Donald G. (eds.), "The Development of Intelligence in Children.", Studies in individual differences: The search for intelligence., East Norwalk: Appleton-Century-Crofts, pp. 81–111, doi:10.1037/11491-008, retrieved 2024-06-18

- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Th. (1916), "New methods for the diagnosis of the intellectual level of subnormals. (L'Année Psych., 1905, pp. 191-244).", The development of intelligence in children (The Binet-Simon Scale)., translated by Kite, Elizabeth S., Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co, pp. 37–90, doi:10.1037/11069-002, retrieved 2024-06-25

- Binet, A., & Simon, T. (1908). Le développement de l’intelligence chez les enfants (The development of intelligence in the child). L’Année psychologique, 14, 1–94. https://doi.org/10.3406/psy.1907.3737

- Binet, A. (1911). Nouvelles recherches sur la mesure du niveau intellectual chez les enfants d’école [New research on measuring the intellectual level of school children]. L’Année Psychologique, 17, 145–201. https://doi.org/10.3406/psy.1910.7275

- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Théodore (1904). "Application des méthodes nouvelles au diagnostic du niveau intellectuel chez des enfants normaux et anormaux d'hospice et d'école primaire". L'Année psychologique. 11 (1): 245–336. doi:10.3406/psy.1904.3676.