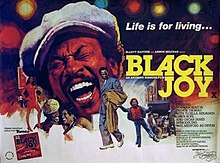

Black Joy is a 1977 British film directed by Anthony Simmons. The story of an immigrant country boy in Brixton, London. It was entered into the 1977 Cannes Film Festival.[5]

| Black Joy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Anthony Simmons |

| Screenplay by | Jamal Ali |

| Based on | Dark Days and Light Nights (play) by Jamal Ali |

| Produced by | Elliott Kastner Arnon Milchan Martin Campbell |

| Starring | Norman Beaton Trevor Thomas |

| Cinematography | Phil Meheux |

| Edited by | Thom Noble |

| Music by | Gladys Knight & the Pips Aretha Franklin Jimmy Helms The Drifters Ben E. King The O'Jays |

| Distributed by | Hemdale Film Distributors[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £31,720[2][3] or $350,000[4] |

| Box office | £87,576[2] |

The film is a lightly ironic, British culture-clash comedy. Trevor Thomas stars as a Guyanese youth who is under the delusion that life will be easier for him in London. No sooner does Thomas set foot in England than he gets tangled up in one disaster after another. The catalyst for most of Our Hero's travails is "assimilated" Caribbean Norman Beaton, who plays a streetwise con artist.

The film was adapted from Dark Days and Light Nights, a stage play by Jamal Ali, who also wrote the screenplay.

Plot

editIn London in the late 1970s, Guyanese immigrant Ben Jones arrives at Heathrow Airport with a suitcase and a wallet full of money. Immigration officials refuse to believe his naïve explanation that the cash was given by his grandmother, and strip-search him. Humiliated and confused, Ben travels to Brixton in search of an obscure address. A ten-year-old boy, Devon, spots him and offers to help find the address if Ben pays him. When Ben foolishly reveals his fat wallet, Devon runs off with it, and Ben is forced to sleep at the local hostel. Dave King, a charismatic petty crook and lover of Devon's mother Miriam, pretends to be a responsible adult and intercepts Ben's wallet, but he keeps the money knowing that Devon has stolen it. That evening, Dave tries to seduce Miriam but she resists him, explaining that she has recently become pregnant. An argument ensues and Miriam forces Dave to leave.

Ben almost loses his suitcase at the hostel, but defends himself against the thief. In an attempt to find his missing wallet he follows Devon around Brixton, but is sidetracked by Devon's beautiful aunt Saffra. At Miriam's café, Ben confronts Devon about the stolen wallet but Dave intercedes and calms the situation, hiding Devon's guilt and befriending Ben by loaning him some money. Unaware that Dave's cash comes from his own stolen wallet, Ben accompanies Dave to a betting shop and defends him in a brawl. They place a bet on a horse that wins and Ben puts his winnings towards new accommodation. He finds a job as a dustman but loses it all again when he gives his earnings to a fraudulent landlord. Desperate for somewhere to stay, Ben appeals to Dave to share a flat. Once he realises that Ben now has a steady income Dave agrees to the flat-share and imposes a set of slanted rules that Ben is too naïve to reject.

Ben uses his new income to decorate the flat and tries to impress Saffra. He gives her a family heirloom – a ring – but Saffra returns it because it is financially worthless. Dave realises that Ben is still a virgin and arranges a trip to Soho where they visit sex shops, strip clubs and a prostitute. At a nightclub Ben meets Sally, a white woman who seduces him, and that night he loses his virginity.

Dave loses all his money in a poker game and goes to Miriam. She is furious and upset, having just returned from an abortion clinic. Dave is hurt that the unborn child has been aborted without his knowledge but this serves to anger Miriam more. With encouragement from Sally, Ben confronts Dave about the degree to which he has abused their friendship. Dave implies that Ben's naivety was as much to blame for his being duped as Dave's own immoral behaviour. Ben, now wiser, agrees to remain friends.

In a bid to cement his relationship with Miriam and Ben, Dave takes advantage of a car deal arranged by Jomo, a loan shark and sometime boyfriend of Saffra. Taking Jomo's new Buick and money, he drives Miriam, Ben and Saffra to Margate for an overnight trip. The four spend a lot of money and Dave loses the rest at a casino. Ben and Saffra sleep together but Saffra remains non-committal. In the morning Dave approaches Ben for some cash to pay the bills he cannot afford. Ben refuses, but suggests that he buys Jomo's car and insists on a receipt. Dave reluctantly agrees and the group return to London.

Once in Brixton, Ben refuses to resell the Buick, putting Dave in a dangerous position with Jomo. Jomo tries to force the sale but is overpowered by Ben who makes it clear he will not be bullied. Jomo backs down and Dave is thankful. Devon and Saffra join Ben in the Buick and they drive away.

Cast

edit- Norman Beaton as Dave King

- Trevor Thomas as Ben Jones

- Floella Benjamin as Miriam

- Dawn Hope as Saffra

- Oscar James as Jomo

- Paul J. Medford as Devon

- Vivian Stanshall as the warden

Soundtrack

editThe soundtrack album contains hits by a number of Soul/R&B stars from the 1960s and '70s:

- Jimmy Helms – "Black Joy"

- Labelle – "Lady Marmalade"

- Moments & Whatnauts – "Girls"

- The Drifters – "Saturday Night At The Movies"

- Johnny Nash – "Tears On My Pillow"

- Shirley & Company – "Shame, Shame, Shame"

- The Real Thing – "Dance With Me"

- The Three Degrees – "When Will I See You Again"

- The Cimarons – "Living On The Dole"

- Billy Paul – "Me & Mrs. Jones"

- Spinners – "The Rubber Band Man"

- Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes – "Don't Leave Me This Way"

- Gladys Knight & the Pips – "Midnight Train To Georgia"

- The O'Jays – "Darlin' Darlin' Baby"

- Biddu Orchestra – "Summer Of '42"

- The Real Thing – "Lightning Strikes Again"

- Aretha Franklin – "I Say A Little Prayer"

- Bill Fredericks – "Love With You"

- Ben E. King – "Stand By Me"

- Lee Vanderbilt – "Lonely I"

- Linda Lewis – "It's In His Kiss"

- The Cimarons – "Black Joy"

Reception

editThe Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "Shot entirely on location in Brixton ...for £150,000, Anthony Simmons' third feature is, though flawed, the most consistently accurate commercial film to deal with Britain's immigrant communities. Simmons has said of Black Joy:'I wanted to show the reality of life in an immigrant area, angry and frustrated like so many other parts of Britain – but full of hope and humour'. What he has certainly succeeded in doing, by concentrating on the hope and humour, is capturing part of the reality of life. The exuberant energy bursting from every frame, combined with the (over-emphasised) Dickensian aspects of the community life, leads one to admit that Simmons has rather overlooked the harsher realities and produced instead an enjoyable lightweight 'musical fable'. (Lou Reizner's amazing soundtrack adds immeasurably to the film, giving the impression of collecting – through the many artists and styles represented – all that is best a in one continuous, marvellous sound.) This impression is reinforced by the fact that the question of integration with the white population is completely excluded; indeed, apart from a few brief, jokey cameos, Ben might have moved into a totally alienaisolatedted black community which is clearly only partially true. However, if one has to be content with the spirit of black joy, then Simmons and co-writer Jamal Ali certainly ensure that it is extremely infectious and entertaining, notably in the splendid dialogue, which is inimitably salty ... and coarsely funny. Although some of the acting is over-strident, the two main roles are both excellently played: Norman Beaton, ideally cast as the flashy, untrustworthy but likeable rogue, Dave; and particularly Trevor Thomas in the more difficult, utterly conventional part of the perennial innocent."[6]

References

edit- ^ "Black Joy (1977)". BBFC. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ a b Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 357. Income is distributor's receipts, combined domestic and international, as at 31 Dec 1978.

- ^ Alexander Walker, National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and Eighties, Harrap, 1985 p 242

- ^ Champlin, Charles (1 June 1977). "CANNES TRIO WITH BRIO: Inventions, Ironies, Immigrants". Los Angeles Times. p. f10.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Black Joy". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ "Black Joy". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 44 (516): 227. 1 January 1977 – via ProQuest.