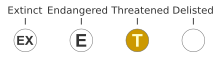

The blackside dace (Chrosomus cumberlandensis)[4] is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Cyprinidae. It is endemic to the Cumberland River drainage in Kentucky and Tennessee as well as the Powell River drainage in Virginia in the United States. It is a federally listed threatened species.[2][3]

| Blackside dace | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Subfamily: | Leuciscinae |

| Clade: | Laviniinae |

| Genus: | Chrosomus |

| Species: | C. cumberlandensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chrosomus cumberlandensis (W. C. Starnes & L. B. Starnes, 1978)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Phoxinus cumberlandensis Starnes & Starnes, 1978 | |

Description

editThis fish is 50 to 65 millimetres (2.0 to 2.6 in) in length. It is olive green in color with black speckling and a black stripe. During the breeding season in April through July the stripe becomes a deeper black, there are red areas on the upper parts, and the fins become yellow.[5]

Ecology

editThis fish is found in 105 streams in Kentucky and Tennessee, but many of these populations are very small, with under 10 individuals. The species has been found in western Virginia, but these populations may have been introduced by people[5] or represent undescribed species.[1]

The fish lives in cool, clear streams with rocky substrates and overhanging vegetation. It is schooling and lives under banks and rock formations. Other fish in the habitat include the common creek chub (Semotilus atromaculatus), white sucker (Catostomus commersoni), stoneroller (Campostoma anomalum), and stripetail darter (Etheostoma kennicotti). The dace eats algae and sometimes insects. It lives 2–3 years and becomes sexually mature in its first year.[6] The female lays an average of 1540 eggs.[7]

Population threats

editThe species is threatened by the loss and degradation of its habitat. The rocky riverbed substrates in which it spawns are degraded by erosion and sedimentation, which are increased by human activities such as runoff pipes from septic tanks, and trash being dumped into streams. Several populations have been extirpated by these processes.[6]

In 2007 a large scale die-off of aquatic life, including blackside dace, occurred in the Acorn Fork in Kentucky. Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that the most likely cause was a spill of hydraulic fracturing fluid from nearby natural gas wells. The results of a joint study indicated that the spill caused a spike in acidity, as well as toxic concentrations of heavy metals.[8][9]

References

edit- ^ a b NatureServe (2014). "Chrosomus cumberlandensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T17064A15364473. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T17064A15364473.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Blackside dace (Phoxinus cumberlandensis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b USFWS (12 June 1987). "Determination of threatened species status for Blackside Dace". Federal Register. 52 (113): 22580–22585. 52 FR 22580

- ^ Chrosomus cumberlandensis. FishBase.

- ^ a b Johnson, T. D., et al. Blackside Dace Phoxinus cumberlandensis Species account and Cumberland Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) survey results. Archived March 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Eisenhour, D. J. and R. M. Strange. (1998). Threatened fishes of the world: Phoxinus cumberlandensis Starnes & Starnes, 1978 (Cyprinidae). Environmental Biology of Fishes 51(2) 140.

- ^ Starnes, L. B. and W. C. Starnes. (1981). Biology of the Blackside Dace Phoxinus cumberlandensis. American Midland Naturalist 106(2) 360–71.

- ^ "Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids Likely Harmed Threatened Kentucky Fish Species". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service News Release. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Papoulias, Diana M.; Velasco, Anthony L. (2013). "Histopathological Analysis of Fish from Acorn Fork Creek, Kentucky, Exposed to Hydraulic Fracturing Fluid Releases". Southeastern Naturalist. 12 (4): 92–111. doi:10.1656/058.012.s413. S2CID 83656785.