The Blau Monuments are a pair of inscribed stone objects from Mesopotamia now in the British Museum.[1] They are commonly thought to be a form of ancient kudurru (boundary marker stone).[2]

| Blau Monuments | |

|---|---|

The Blau Monuments, British Museum | |

| Material | Gypsum |

| Size | 96.5 cm long |

| Created | 3100-2700 BC |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1928,0714.1 |

History

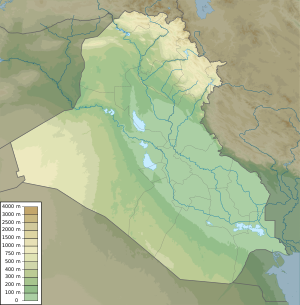

editThe Monuments were purchased by A. Blau in 1886 near the city of Uruk (modern-day Iraq). They were eventually acquired by the British Museum.[3] They were carved of bright blue stone commonly regarded as a dark shale or kind of schist.[2] Thought to be forgeries for some time,[4][5] excavations at Uruk redeemed them through revealing stylistic parallels in a basalt stele and the famous Warka Vase. Some assyriologists accepted the Monuments’ authenticity as early as 1901, although this was not a universal belief.[6][7] Even though widely accepted today, some authors nonetheless maintain scrutiny on the Monuments’ status within Mesopotamian history.

Dating

editThe Blau Monuments are dated within the Uruk III/Jemdet Nasr to Early Dynastic I period. Some authors date the pair as early as 3100 BC on the basis of the Proto-Cuneiform script, while others date them to the ED I period around 2700 BC because of other stylistically similar land sale records with a definite date in the ED I period. Both dates are equally represented in scholarly works; the majority of works citing the earliest date usually reference Gelb in their turn.[6][4][5][2][8][9]

Imagery

editThe iconography on the Monuments is a matter of some dispute, upon which even recent scholars cannot wholly agree. Throughout their history, it has been consistently believed that the Monuments represented some form of transaction, usually in the form of a gift from a temple to its craftsmen.[4][5][10] More recently, the imagery has been taken to represent a ceremonial feast given by a new land-owner after a land purchase.[2]

Obelisk (BM 86261)

editThe obelisk (18 cm × 4.3 cm × 1.3 cm) shows male forms in two separate registers. The lower figure is a nude male who kneels with a pestle and mortar, which could suggest equally craftsmen or food preparation. He has parallels on the Warka Vase, where likewise nude males carry baskets of food for religious purposes.[11]

In the upper register, a standing man with a beard, bordered net-skirt, and headband holds a four-legged animal in his hands (usually identified as either a sheep or a goat). This figure is a very common way throughout Mesopotamian art of depicting a male with power. This is generally considered as a depiction of a "Priest-King".[11]

Plaque (BM 86260)

editThe obverse of the plaque (15.9 cm × 7.2 cm × 1.5 cm) shows a similarly hierarchical scene. The leftmost figure is another bearded, skirted man. He holds a long object with both hands. This object has been interpreted as a pestle or a land-sale cone; when compared to the workers elsewhere on the Monuments who are working with pestles, the former identification seems unlikely. This is generally considered as another depiction of the "Priest-King".[11] The "Priest King" appears on numerous works of art of the period, and even on a prehistoric Egyptian knife, the Gebel el-Arak Knife, suggesting Egypt-Mesopotamia relations at the time.[11]

Most texts identify the right figure as a woman on the basis of Gelb’s identification, but if so, then ‘she’ lacks the characteristic dress present on other women from the same period, such as on the Ushumgal Stele. The reverse shows four men. Two are nude workers, kneeling with pestles and mortars. Between them stands a bald man wearing a net skirt. He holds his hands up like the smaller figure on the obverse. The remaining figure sits to the right, and appears nearly identical to the workers except slightly larger. This evidently depicts the process of food preparation for the feast.[2][11]

Inscriptions

editLike the Stele of Ushumgal and other works from a similar time period, the text on the Blau Monuments is not fully comprehensible. Certain signs are readily identified, while others have no known identification. The obelisk’s inscription clearly refers to "5 bur" of land (roughly 30 hectares), as well as a temple household and the profession "engar". This title refers to a high official in an agricultural field, which would suggest the presence of an individual able to undertake such a transaction. The plaque’s text lists commodities of many sorts, as well as several other names and additional undeciphered information. The assumption, then, is that these items were exchanged for the land on the obelisk.[12]

Controversy

editAs a result of the yet-undeciphered text and certain oddities in the iconography, any attempt at definitively declaring a purpose for the Monuments is naturally tenuous. The Monuments are two of only five “ancient kudurrus” listed by Gelb (a classification currently in dispute).[13] Consequently, they resist classification, and such a task is certainly not aided by the lack of definite information on their use.

References

edit- ^ British Museum Highlights

- ^ a b c d e I. J. Gelb, P. Steinkeller, and R. M. Whiting Jr, "OIP 104. Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus", Oriental Institute Publications 104 Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 1989, 1991 ISBN 978-0-91-898656-6 Text Plates

- ^ Reade, Julian E. (2000), “Early Carvings from the Mocatta, Blau, and Herzfeld Collections”, in: Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2000/71, 81–8

- ^ a b c Mallowan, Max E. L. (1961a). Early Mesopotamia and Iran. London: Thames & Hudson

- ^ a b c 1961b). The Birth of Written History. In: The Dawn of Civilization. Ed. by Stuart Piggott. London: Thames & Hudson, 65–96

- ^ a b Barton, George A. “Some Notes on the Blau Monuments.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 22, 1901, pp. 118–25

- ^ Barton, George A. “A New Collation of the Blau Monuments.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 24, 1903, pp. 388–89

- ^ Millard, A. 1998 "Books in the Late Bronze Age in the Levant" in Israel Oriental Studies Vol 18 (Anson F. Rainey festschrift), 171–181

- ^ Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11032-7

- ^ British Museum. Dept. of Western Asiatic Antiquities; Richard David Barnett; Donald John Wiseman (1969). Fifty masterpieces of ancient Near Eastern art in the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities, the British Museum. British Museum. p. 41. ISBN 9780714110691

- ^ a b c d e Collon, Dominique (1995). Ancient Near Eastern Art. University of California Press. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780520203075.

- ^ [1] Krebernik, Manfred. "Towards the Deciphering of the “Blau Monuments”: Some New Readings and Perspectives." Culture and Cognition: 35., In: Jürgen Renn and Matthias Schemmel (eds.): Culture and Cognition : Essays in Honor of Peter Damerow, CHapter 4, 2019 ISBN 978-3-945561-35-5

- ^ Kathryn E. Slanski, "The Babylonian entitlement narûs (kudurrus) : a study in their form and function", Boston : American Schools of Oriental Research, 2003 ISBN 089757060X

Further reading

edit- Balke, Thomas E., "The Interplay of Material, Text, and Iconography in Some of the Oldest “Legal” Documents". Materiality of Writing in Early Mesopotamia, edited by Thomas E. Balke and Christina Tsouparopoulou, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 73–94, 2016

- Boese, Johannes, "Die Blau’schen Steine und der Priesterfürst im Netzrock", in: Altorien-talische Forschungen 37, pp. 208–22, 2010

- Thureau-Dangin, F., "Recherches sur l'origine de l'ecriture cunéiforme. 1re partie, Les formes archaïques et leurs équivalents modernes", Paris: Leroux, 1898