This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

The Blockade of Africa began in 1808 after the United Kingdom outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, making it illegal for British ships to transport slaves. The Royal Navy immediately established a presence off Africa to enforce the ban, called the West Africa Squadron. Although the ban initially applied only to British ships, Britain negotiated treaties with other countries to give the Royal Navy the right to intercept and search their ships for slaves.[1]

| Blockade of Africa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Suppression of the African slave trade | |||||||

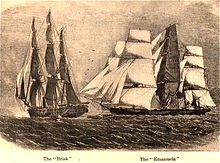

HMS Brisk capturing the Spanish slave ship Emanuela. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Slave traders | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Francisco Félix de Souza | |||||||

The 1807 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves abolished the intercontinental slave trade in the United States but was not widely enforced. From 1819, some effort was made by the United States Navy to prevent the slave trade. This mostly consisted of patrols of the shores of the Americas and in the mid-Atlantic, the latter being largely unsuccessful due to the difficulty of intercepting ships mid-ocean. As part of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, it was agreed that both countries would work together on the abolition of the slave trade, which was deemed piracy, and to continue the blockade of Africa. US Navy involvement continued until the beginning of the American Civil War, in 1861. The following year, the Lincoln administration gave the UK full authority to intercept US ships. Slavery was not abolished in the United States until 1865, when Congress ratified the 13th Amendment. The Royal Navy squadron remained in operation until 1870.

United Kingdom involvement

editBackground

editThe Slave Trade Act 1807 stated that:

The African Slave Trade, and all manner of dealing and trading in the Purchase, Sale, Barter, or Transfer of Slaves, or of Persons intended to be sold, transferred, used, or dealt with as Slaves, practised or carried on, in, at, to or from any Part of the Coast or Countries of Africa, shall be, and the same is hereby utterly abolished, prohibited, and declared to be unlawful.

Under this act, if a ship was caught with slaves, there was a fine of £100 per enslaved person. This fine was usually paid by the ship's captain.[2]

In order to enforce this, two ships were dispatched to the African coast, their primary mission being to prevent British subjects from slave trading and also to disrupt the slave trades of the UK's enemies during the Napoleonic Wars.

Diplomacy

editThe original 1807 Act only allowed for British ships to be searched and applied only to British subjects. The slave trade on the African coast therefore continued, though without the presence of British slavers, at least on a legal basis. However, in 1810, under considerable diplomatic pressure, a convention with Portugal was signed, widening the mandate of the Royal Navy.[3][4] In 1815, Portugal strengthened their anti-slavery legislation by abolishing all trade north of the equator, allowing the Royal Navy a much freer hand. With the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain obtained treaties with several other powers, including France, which abolished its trade entirely in 1815 (but did not commit to right of search), and Spain, which agreed to cease trade north of the equator in 1818, and south of the equator by 1820.[5][6] A clause was also inserted into the Congress of Vienna, which called for the eventual abolition of the trade by all signatories. In 1826, Brazil signed an agreement similar to that of Portugal and ceased trade north of the equator.

The UK's slave trade suppression efforts attempted to remain within the primitive international laws of the time: slavers had to be tried in courts. British vessels were taken to vice admiralty courts, and those of foreign states that had treaties with the UK were taken to Courts of Mixed Commission. Mixed Commission Courts had representation from both the UK and the other nation in question, to ensure a fair trial. Many were established at key points along the coast of Africa and its islands. However, the reluctance of other powers greatly curtailed the ability of the courts to operate. Sometimes, the foreign representation would never arrive, or arrive exceptionally late. The Brazilian ambassador, in spite of the court opening in 1826, did not arrive until 1828, and he reversed all judgements carried out in his absence upon arrival.[7]

In addition to the issues with Mixed Commission Courts, the Navy's mandate to police the trade was also found to be lacking and built on a series of complicated and often weak diplomatic treaties between other states. The agreements were signed reluctantly and were therefore very weak in practice.[8] When policing foreign vessels, there had to be slaves on board at the time of seizure for the accused slaver to be convicted. Unlike in Britain's 1807 Act, there was no equipment clause, meaning that slave ships carrying what was obviously equipment for transporting slaves, but without slaves on board at the time of search, could not be seized. This major flaw, which greatly curtailed the navy's efforts and caused some naval officers to fall foul of the law, was not rectified until the 1830s. Frustrated with the lack of progress, in 1839, the British government subjected Portuguese vessels to British jurisdiction and did the same to Brazilian vessels in 1845. This was an unprecedented step, which subjected foreign vessels to the much more stringent British law and much stricter penalties for slave trading.

However, some nations, such as the United States, resisted British coercion. The US believed strongly in freedom of the seas and on several occasions refused to allow the Royal Navy right of search. Knowing that many slavers would fly false US flags to avoid being boarded, some slavers were even registered in southern US states. This caused several diplomatic incidents, as frustrated officers would often board ships with US flags, directly contravening their orders, to capture slavers. There was fierce opposition to this in the US Congress, and John Forsyth said in 1841 that "the persistence" of British cruisers was "unwarranted", "destructive to private interests", and "[would] inevitably destroy the harmony of the two countries".[9] In 1842, there was a thaw in diplomatic relations, and the US allowed visitation to US vessels, but only if a US officer was also present.[10]

With the beginning of the 1850s, Portugal had completely ceased slave trading (1836) and Spain had all but ceased, but Cuba was still an active slave port. Brazil continued to defy British intervention, and the Brazilian trade was not extinguished until 1852, when Palmerston began using force under the Pax Britannica doctrine.[citation needed]

West Africa Squadron

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

The British Royal Navy commissioned the West Africa Squadron in 1807, and the United States Navy did so as well in 1842. The squadron had the duty to protect Africa from slave traders, and it effectively aided in ending the transatlantic slave trade. In addition to the West Africa Squadron, the Africa Squadron had the same duties to perform. However, they faced a problem with finding enough sailors. The Liberian coastal Kru people were hired, which allowed the West African Squadron to patrol the coast of Africa effectively. Following the 1807 Act, two ships had been dispatched to the African coast for anti-slavery patrol.[citation needed]

By 1818, the squadron had grown to six ships, with a naval station established in 1819 at what is now Freetown and a supply base at Ascension Island, later moved to Cape Town in 1832.[citation needed]

These resources were further increased: in the middle of the 19th century, there were around 25 vessels and 2,000 personnel, with a further 1,000 local sailors.[11] Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron captured 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans.[12] Around 2,000 British sailors died on their mission of freeing slaves with the West Africa Squadron.[13][14]

End of the trade

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

In spite of Britain's best efforts to pursue suppression through diplomatic means, the trade persisted. Public opinion was beginning to turn against the anti-slavery efforts due to their huge costs, the diplomatic repercussions they created, and the damage caused to other trade.[15] Opposition in the Commons emerged from anti-coercionists, who were opposed to the use of British coercion of other nations and prolonged military action against slavers. The anti-coercionists were a mixed group of free trade activists and anti-slavery advocates who saw the only way to end the trade being the establishment of legitimate commerce with Africa. Their leader, Thomas Fowell Buxton, advocated a renewed naval effort until this could be achieved. In 1839, he published The African Slave Trade and its Remedy, which contained a top-to-bottom critique of the British efforts thus far. The work was highly influential and gave Buxton a leading role in the planning of the Niger expedition of 1841, an attempt to establish trading posts along the Niger River to create an alternative to slave trading. Although the plan had offered a long-term solution to the slave trade, the expedition ended in abject failure, with many of the Europeans falling ill. In 1845, Buxton died, with his ambitions unfulfilled.[citation needed]

From 1845, the anti-coercionist cause became much more radical and much less concerned with the plight of Africans; this "new generation" of anti-coercionists did not include abolitionists. Free trade advocates such as William Hutt were vehemently opposed to naval actions and argued the trade would eventually die naturally and the UK's interference was unwarranted. Such was their influence that there was even a motion in the Commons to end all naval activity, which came close to ending the West Africa Squadron and also the career of Prime Minister John Russell, who threatened resignation should the motion be carried.[16]

To prevent a repeat of this, swift action was taken. Brazil was still one of the largest slave trading nations and continued to defy British diplomatic calls to put an end to the practice. In 1846, Palmerston returned as foreign secretary and in 1850 permitted Royal Naval vessels to enter Brazilian waters in order to blockade slavers on both sides of the Atlantic. By 1852, the Brazilian trade could be said to be extinct.[17] "For Palmerston … the naval campaign on the coast of Brazil had brought the long drawn-out saga of the Brazilian slave trade to a resolution within twelve months".[18]

The many years of British pressure on the United States to join vigorously in fighting the Atlantic slave trade had been neutralised by the southern states. However, with the onset of the American Civil War, the Lincoln administration became eager to sign up, humanitarian and military objectives combined. To the North, anti-slavery was an important military tool with which to harm the Confederate economy. It also won praise, sympathy, and support on the international stage and dampened international support for the Southern States, who vehemently defended their right to keep slaves. In the Lyons–Seward Treaty of 1862, the United States gave the UK full authority to crack down on the Atlantic slave trade when carried on by US ships.[19] With the end of hostilities the UK and the US would continue cooperating, and in 1867, Cuba, under much pressure from the two nations, gave up its trade.[citation needed]

United States involvement

editThe United States Constitution of 1787 had protected the importation of slaves for twenty years. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society held its first meeting at the temporary capital, Philadelphia, in 1794. On 7 April 1798, the fifth Congress passed an act that imposed a $300-per-slave penalty on persons convicted of performing the illegal importation of slaves. It was an indication of the type of behaviour and course of events soon to become commonplace in the Congress.

On Thursday, 12 December 1805, in the ninth Congress, Senator Stephen Roe Bradley of the State of Vermont gave notice that he should, on Monday next, move for leave to bring in a bill to prohibit the importation of certain persons therein described "into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States, from and after the first day of January", which will be "in the year of our Lord 1808". His words would be repeated many times by the legislators in the ninth Congress. The certain persons were described as being slaves on Monday, 16 December 1805.

Wary of offending slaveholders to the least degree, the Senate amended the proposed Senatorial Act, then passed it to the House of Representatives, where it was meticulously scrutinised. Ever mindful of not inciting the wrath of slaveholders, members of the House produced a bill that would explain the Senatorial Act. The two measures were bound together, with the House bill being called H R 77 and the Senate Act being called An Act to prohibit the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States, from and after the first day of January, in the year of our Lord, 1808. The bond measure also regulated the coastwise slave trade. The bond measure was placed before President Thomas Jefferson on 2 March 1807 for his approbation.

The 1807 Act of Congress was modified and supplemented by the Fifteenth Congress. The importation of slaves into the United States was called "piracy" by an Act of Congress that punctuated the Era of Good Feelings in 1819. Any citizen of the United States found guilty of such "piracy" might be given the death penalty. The role of the Navy was expanded to include patrols off the coasts of Cuba and South America. The naval activities in the western Atlantic bore the name of "The African Slave Trade Patrol of 1820–61". The blockade of Africa was still being performed in the eastern Atlantic at the same time.

Africa Squadron operations

editAmerican naval officer Matthew Calbraith Perry was the executive officer aboard HMS Cyane in 1819, which had escorted the Elizabeth, whose passengers included former slaves moving from the United States to Africa. President James Monroe had the Secretary of the Navy order the American vessel to convoy the Elizabeth to Africa with the first contingent of freed slaves that the American Colonization Society was resettling there. Of the 86 black emigrants sailing on the Elizabeth, only about one-third were men; the rest were women and children. In 1821, Perry commanded USS Shark in the Africa Squadron. USS Alligator, under the command of Lieutenant Robert F. Stockton, was also in the African Squadron in 1821 and captured several slavers. Lieutenant Stockton also convinced the local African chief to relinquish land around Cape Mesurado, where Liberia eventually formed. Stockton became the commander of the US Navy's first screw-propelled steamer, USS Princeton, in 1843.

On 26 and 27 November 1842, aboard USS Somers in the African Squadron, commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie ordered the arrest of three crewmen who were plotting to take control of the ship. The three were hanged on 1 December. This is the only occurrence of maritime mutiny at law in the history of the United States Navy.[citation needed]

Commodore Perry was placed in command of the African Squadron in 1843. Ships that captured slavers while deployed with the African Squadron include USS Yorktown, USS Constellation, and the second USS Constellation, which captured Cora on 26 September 1860, with 705 Africans on board. The first USS San Jacinto captured the brig Storm King on 8 August 1860, off the mouth of the Congo River, with 619 Africans on board.[20][21] In her final act, USS Constitution captured H.N. Gambrill in 1853.

The Navy attempted to intercept slave ships from 1808 (or 1809) to 1866. A small number of ships were accosted; some of them were carrying Africans destined to be sold into slavery, while others, which had no slaves on board, were captured and escorted away from the coast of Africa.

Black Ivory

editThis section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as This section seems somewhat out of place in the whole article. It reiterates a few previous points, mentions marginally relevant political events, and overall seems to fit poorly.. (July 2023) |

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 created great demand for more slaves to work in the vast new area. Jean Lafitte was a pirate who brought many slaves to the United States and sold them through an organised system established at New Orleans that included merchants from the vicinity. After he helped Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812, President James Madison issued a proclamation early in 1815 granting him and his men pardons for their misdeeds.

The United States Navy's Africa Squadron, Brazil Squadron, and Home Squadron were assigned the task of intercepting ships that were bringing Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the slave markets, where black ivory found numerous customers. Since the War of Independence had been costly, no American warships were constructed between 1783 and 1795. The Navy Department was created on 30 April 1798. On 27 March 1794, following communication with President Washington, Congress authorised the purchase or construction of six frigates. These ships included the first USS Constellation, launched 7 September 1797, and USS Constitution, a ship that would be briefly employed in the African Squadron. Few new ships were built in the United States after 1801 until USS Guerriere was launched on 20 June 1814; it proved to be an effective warship in the war with the Barbary pirates in 1815.

At the same time as this effort was taking place, other important tasks, such as the War of 1812, the ongoing troubles with the Barbary pirates, the extermination of the pirates in the West Indies from 1819 to 1827, the protection of American shipping in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Peru in the 1830s, the War with Mexico in the 1840s, the voyages to Japan in the 1850s, and transporting of diplomats to other nations left little capability available for use in the African Squadron.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007). Encyclopedia of the middle passage. Greenwood Press. pp. xxi, xxxiii–xxxiv. ISBN 9780313334801.

- ^ "Notes on contributors". Slavery & Abolition. 17 (1): 155–156. April 1996. doi:10.1080/01440399608575180. ISSN 0144-039X.

- ^ Christoper Lloyd, The Navy and the Slave Trade p. 62

- ^ TNA ADM 2/1327 Standing Orders to Commanders-in-Chief 1815–1818

- ^ Bethell, L. "The Mixed Commissions for the Suppression of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1966) p. 79

- ^ Reginald Coupland The British Anti-Slavery Movement pp. 151–60

- ^ Shaikh, F 'Judicial Diplomacy: British Officials and the Mixed Commission Courts' in Slavery Diplomacy and Empire p. 44

- ^ Wilson, H. H, 'Some Principal Aspects of British Efforts to Crush the African Slave Trade, 1807–1929' The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 44, No. 3 (1950) p. 509-510

- ^ Seizure of American Vessels – Slave Trade in Eltis, D. Abolition of the Slave Trade: Suppression <url: http://abolition.nypl.org/content/docs/text/seizure_american_vessels.pdf>

- ^ Parliamentary Papers, 1844, Vol. L [577] "Instructions for the guidance of Her Majesty's naval officers employed in the suppression of the slave trade", pp. 12–13

- ^ Lewis-Jones, Huw. "The Royal Navy and the Battle to End Slavery". BBC History.

- ^ "Royal Navy sailors died while preventing the slave trade, but not tens of thousands". Full Fact. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Chasing Freedom Information Sheet". National Museum of the Royal Navy. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Richard Huzzey, Freedom Burning p. 116

- ^ Reginald Coupland, Anti-Slavery Movement p. 182

- ^ Wilson, H. H, 'Some Principal Aspects of British Efforts to Crush the African Slave Trade, 1807–1929' The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 44, No. 3 (1950)

- ^ Lambert, A. 'Slavery, Free Trade, and Naval Strategy, 1840–1860' in Slavery Diplomacy and Empire, ed. Hamilton K. & Salmon, P. (Eastbourne, Sussex Academic Press 2009)p. 72

- ^ Conway W. Henderson, "The Anglo-American Treaty of 1862 in Civil War Diplomacy." Civil War History 15.4 (1969): 308–319. online

- ^ "Two More Slavers Captured" (PDF). The New York Times. 27 September 1860. p. 5. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Hamersly, Lewis Randolph (1902). "Aaron Konkle Hughes". The Records of Living Officers of the U. S. Navy and Marine Corps: Compiled from Official Sources. New York, New York: L. R. Hamersly Co. pp. 28–30. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

External links

edit- Chasing Freedom: The Royal Navy and the Suppression of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at the Wayback Machine (archived 19 August 2000)

- USS Somers at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 8 June 2011)

- USS Alligator at the Wayback Machine (archived 2 March 2004)

- USS Constitution at the Wayback Machine (archived 19 March 2004)

- USS Chesapeake at the Wayback Machine (archived 15 March 2004)

- USS Saratoga at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 April 2004)

- USS Niagara at the Wayback Machine (archived 16 March 2004)

- USS Dolphin at the Wayback Machine (archived 2 March 2004)