A blockbuster is a work of entertainment—typically used to describe a feature film produced by a major film studio, but also other media—that is highly popular and financially successful. The term has also come to refer to any large-budget production intended for "blockbuster" status, aimed at mass markets with associated merchandising, sometimes on a scale that meant the financial fortunes of a film studio or a distributor could depend on it.

Etymology

editThe term began to appear in the American press in the early 1940s,[1] referring to the blockbuster bombs, aerial munitions capable of destroying a whole block of buildings.[2] Its first known use in reference to films was in May 1943, when advertisements in Variety[3] and Motion Picture Herald described the RKO film, Bombardier, as "The block-buster of all action-thrill-service shows!" Another trade advertisement in 1944 boasted that the war documentary, With the Marines at Tarawa, "hits the heart like a two ton blockbuster."

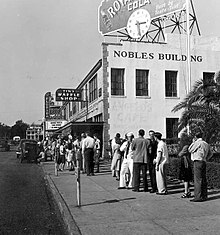

Several theories have been put forward for the origin of the term in a film context. One explanation pertains to the practice of "block booking" whereby a studio would sell a package of films to theaters, rather than permitting them to select which films they wanted to exhibit. However, this practice was outlawed in 1948 before the term became common parlance; while pre-1948 high-grossing big-budget spectacles may be retroactively labelled "blockbusters," this is not how they were known at the time. Another explanation is that trade publications would often advertise the popularity of a film by including illustrations showing long queues often extending around the block, but in reality the term was never used in this way. The term was actually first coined by publicists who drew on readers' familiarity with the blockbuster bombs, drawing an analogy with the bomb's huge impact. The trade press subsequently appropriated the term as short-hand for a film's commercial potential. Throughout 1943 and 1944 the term was applied to films such as Bataan, No Time for Love and Brazil.[4]

History

editGolden Age era

editThe term fell out of usage in the aftermath of World War II but was revived in 1948 by Variety in an article about big budget films. By the early 1950s the term had become standardised within the film industry and the trade press to denote a film that was large in spectacle, scale and cost, that would go on to achieve a high gross. In December 1950 the Daily Mirror predicted that Samson and Delilah would be "a box office block buster", and in November 1951 Variety described Quo Vadis as "a b.o. blockbuster [...] right up there with Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind for boxoffice performance [...] a super-spectacle in all its meaning".[4]

According to Stephen Prince, Akira Kurosawa's 1954 film Seven Samurai had a "racing, powerful narrative engine, breathtaking pacing, and sense-assaulting visual style" (what he calls a "kinesthetic cinema" approach to "action filmmaking and exciting visual design") that was "the clearest precursor" and became "the model for" the "visceral" Hollywood blockbuster "brand of moviemaking" that emerged in the 1970s. According to Prince, Kurosawa became "a mentor figure" to a generation of emerging American filmmakers who went on to develop the Hollywood blockbuster format in the 1970s, such as Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola.[5]

Blockbuster era

edit1970s

editIn 1975, the usage of "blockbuster" for films coalesced around Steven Spielberg's Jaws. It was perceived as a new cultural phenomenon: fast-paced, exciting entertainment, inspiring interest and conversation beyond the theatre (which would later be called "buzz"), and repeated viewings.[6] The film is regarded as the first film of the "blockbuster era", and founded the blockbuster film genre.[7] Two years later, Star Wars expanded on the success of Jaws, setting box office records and enjoying a theatrical run that lasted more than a year.[8] After the success of Jaws and Star Wars, many Hollywood producers attempted to create similar "event" films with wide commercial appeal, and film companies began green-lighting increasingly large-budget films, and relying extensively on massive advertising blitzes leading up to their theatrical release. These two films were the prototypes for the "summer blockbuster" trend,[9] in which major film studios and distributors planned their annual marketing strategy around a big release by July 4.[10] Alongside other films from the New Hollywood era, George Lucas's 1973 hit American Graffiti is often cited for helping give birth to the summer blockbuster.[11]

1980s–1990s

editThe next fifteen years saw a number of high-quality blockbusters released including the likes of Alien (1979) and its sequel, Aliens (1986), the first three Indiana Jones films (1981, 1984 and 1989), E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Ghostbusters (1984), Beverly Hills Cop (1984), the Back to the Future trilogy (1985, 1989 and 1990), the Steven Spielberg-produced An American Tail (1986), Top Gun (1986), Die Hard (1988), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Batman (1989) and its sequel Batman Returns (1992), The Little Mermaid (1989), The Hunt for Red October (1990), The Lion King (1994) and Toy Story (1995).[12][13][14][15][16][17]

21st century

editSome examples of summer blockbusters from the 2000s include Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003), The Da Vinci Code (2006), Transformers (2007) and Iron Man (2008)[18]—all of which founded successful franchises—and originals like The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and Pixar's Finding Nemo (2003), WALL-E (2008) and Up (2009).[19] The superhero genre saw renewed interest with X-Men (2000), Spider-Man (2002), Batman Begins (2005) and its sequel The Dark Knight (2008) all proving to be very popular.[20]

Blockbusters in the 2010s include Inception (2010), Despicable Me (2010), Ted (2012), The Conjuring (2013), Frozen (2013),[21][22][23] Edge of Tomorrow (2014) and Wonder Woman (2017). Snowpiercer (2014) proved to be the rare example of an international blockbuster that did not perform well in the North American market. Several established franchises continued to spawn successful entries with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011), X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014), Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) and Pixar's Toy Story 3 (2010) and Incredibles 2 (2018) among the highlights. Several older franchises were successfully resurrected by Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Jurassic World (2015), Man of Steel (2013), Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) and its sequel War for the Planet of the Apes (2017). The most successful franchise of the decade was arguably Disney's Marvel Cinematic Universe, particularly The Avengers series.[24]

Blockbusters in the 2020s include Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,[25] The Super Mario Bros. Movie,[26] and Greta Gerwig's adaptation of Barbie (each from 2023)[27] alongside several older franchises that were successfully resurrected like Top Gun: Maverick (2022)[28][29] and Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (2024).[30]

Criticism

editEventually, the focus on creating blockbusters grew so intense that a backlash occurred, with some critics and film-makers decrying the prevalence of a "blockbuster mentality",[31] lamenting the death of the author-driven, "more artistic" small-scale films of the New Hollywood era. This view is taken, for example, by film journalist Peter Biskind, who wrote that all studios wanted was another Jaws, and as production costs rose, they were less willing to take risks, and therefore based blockbusters on the "lowest common denominators" of the mass market.[32] In his 2006 book The Long Tail, Chris Anderson talks about blockbuster films, stating that a society that is hit-driven, and makes way and room for only those films that are expected to be a hit, is in fact a limited society.[33] In 1998, writer David Foster Wallace posited that films are subject to an inverse cost and quality law.[34]

Peter Biskind's book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls argues that the New Hollywood movement marked a significant shift towards independently produced and innovative works by a new wave of directors, but that this shift began to reverse itself when the commercial success of Jaws and Star Wars led to the realization by studios of the importance of blockbusters, advertising and control over production (even though the success of The Godfather was said to be the precursor to the blockbuster phenomenon).[35][36]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ "blockbuster | Definition of blockbuster in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ "Advertisement for the film "Bombardier"". Variety. May 12, 1943. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Hall, Sheldon (2014). "Pass the ammunition : a short etymology of "Blockbuster"" (PDF). Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Prince, Stephen (6 November 2015). "Kurosawa's international legacy". In Davis, Blair; Anderson, Robert; Walls, Jan (eds.). Rashomon Effects: Kurosawa, Rashomon and their legacies. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-317-57464-4. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Tom Shone: Blockbuster (2004). London, Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 0-7432-6838-5. See pp. 27–40.

- ^ Neale, Steve. "Hollywood Blockbusters: Historical Dimensions." Ed. Julien Stinger. Hollywood Blockbusters. London: Routeledge, 2003. pp. 48–50. Print.

- ^ "Celebrating the Original STAR WARS on its 35th Anniversary". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ Gray, Tim (2015-06-18). "'Jaws' 40th Anniversary: How Steven Spielberg's Movie Created the Summer Blockbuster". Variety. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ Shone (2004), Chapter 1.

- ^ Staff (May 24, 1991). "The Evolution of the Summer Blockbuster". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2008.

- ^ "Did 'Jaws' and 'Star Wars' Ruin Hollywood?". Ross Douthat. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ The Circle Of Life: 10 Behind-The-Scenes Facts About The Lion King (1994)|Screen Rant

- ^ Toys Are the Story on Holiday Weekend: Disney’s ‘Toy Story’ is Thanksgiving’s big moneymaker. The animated film could propel the five days to a record $152 million in ticket sales. - Los Angeles Times

- ^ Who Framed Roger Rabbit - Museum of the Moving Image

- ^ A Fievel Revival: The 35th Anniversary of "An American Tail"|Cartoon Research

- ^ 1982 and the Fate of Filmgoing|The New Yorker

- ^ Don't Blame Barbie and Ken for Killing the Movies - And Don't Blame IP - IPWatchdog.com

- ^ Summer Blockbusters from the 2000s: 'Gladiator', 'Pirates of the Caribbean', 'Spidr-Man' and More|A.Frame

- ^ "Summer Blockbusters That Defined the 2000s". CBR. July 22, 2020.

- ^ Disney's "Frozen" Becomes Highest-Grossing Animated Film in International Markets|Playbill

- ^ Disney's Oscar-Winning Film "Frozen" Becomes Highest-Grossing Animated Film|Playbill

- ^ Frozen Becomes fifth-biggest film in box office history - BBC News

- ^ "Our 25 Favourite Blockbusters of the 2010s". Gizmodo Australia. July 13, 2020.

- ^ Weekend Animated Box-Office Battle: It’s Sony’s ‘Spider-Verse’ versus Pixar’s ‘Elemental’|Animation Magazine

- ^ Super Mario Bros. Wonder designers first Mario game since its blockbuster movie - WBUR

- ^ ‘Barbie’ Becomes Top-Grossing Movie of 2023 Domestically, Global to Soon Follow - The Hollywood Reporter

- ^ ‘Top Gun: Maverick’ Cruises To No. 2 In Deadline’s 2022 Most Valuable Blockbuster Tournament - Deadline

- ^ ‘Top Gun: Maverick’ Passes ‘The Avengers’ as Ninth-Highest Grossing Domestic Release in History - Variety

- ^ ‘Beetlejuice 2’ Is Going From Nostalgic Success to Blockbuster Hit - The Wrap

- ^ Stringer, Julian (June 15, 2003). Movie Blockbusters. Psychology Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780415256087 – via Google Books.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (1998). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And Rock 'N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ Anderson, Chris. "The Long Tail" (PDF). Chris Anderson. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Foster Wallace, David (November 6, 2012). Both Flesh and Not. New York: Little Brown & Company. ISBN 978-0316182379.

- ^ Biskind (1998), p. 288

- ^ "A Century in Exhibition—The 1970s: A New Hope". Boxoffice. November 27, 2020.