The blue-faced honeyeater (Entomyzon cyanotis), also colloquially known as the Bananabird, is a passerine bird of the honeyeater family, Meliphagidae. It is the only member of its genus, and it is most closely related to honeyeaters of the genus Melithreptus. Three subspecies are recognised. At around 29.5 cm (11.6 in) in length, the blue-faced species is large for a honeyeater. Its plumage is distinctive, with olive upperparts, white underparts, and a black head and throat with white nape and cheeks. Males and females are similar in external appearance. Adults have a blue area of bare skin on each side of the face readily distinguishing them from juveniles, which have yellow or green patches of bare skin.

| Blue-faced honeyeater | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Subspecies cyanotis, Queensland | |||

| Scientific classification | |||

| Domain: | Eukaryota | ||

| Kingdom: | Animalia | ||

| Phylum: | Chordata | ||

| Class: | Aves | ||

| Order: | Passeriformes | ||

| Family: | Meliphagidae | ||

| Genus: | Entomyzon Swainson, 1825 | ||

| Species: | E. cyanotis

| ||

| Binomial name | |||

| Entomyzon cyanotis (Latham, 1801)

| |||

| |||

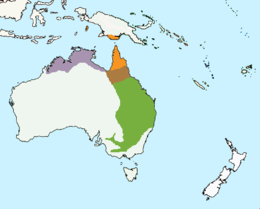

| Range subspecies indicated

| |||

| Synonyms | |||

|

Melithreptus cyanotis | |||

Found in open woodland, parks and gardens, the blue-faced honeyeater is common in northern and eastern Australia, and southern New Guinea. It appears to be sedentary in parts of its range, and locally nomadic in other parts; however, the species has been little studied. Its diet is mostly composed of invertebrates, supplemented with nectar and fruit. They often take over and renovate old babbler nests, in which the female lays and incubates two or rarely three eggs.

Taxonomy and naming

editThe blue-faced honeyeater was first described by ornithologist John Latham in his 1801 work, Supplementum Indicis Ornithologici, sive Systematis Ornithologiae. However, he described it as three separate species, seemingly not knowing it was the same bird in each case: the blue-eared grackle (Gracula cyanotis), the blue-cheeked bee-eater (Merops cyanops), and the blue-cheeked thrush (Turdus cyanous).[2][3] It was as the blue-cheeked bee-eater that it was painted between 1788 and 1797 by Thomas Watling, one of a group known collectively as the Port Jackson Painter.[4]

It was reclassified in the genus Entomyzon, which was erected by William Swainson in 1825. He observed that the "Blue-faced Grakle" was the only insectivorous member of the genus, and posited that it was a link between the smaller honeyeaters and the riflebirds of the genus Ptiloris.[5] The generic name is derived from the Ancient Greek ento-/εντο- 'inside' and myzein/μυζειν 'to drink' or 'suck'. The specific epithet, cyanotis, means 'blue-eared', and combines cyano-/κυανο 'blue' with otis (a Latinised form of ωτος, the Greek genitive of ous/ους) 'ear'.[6] Swainson spelt it Entomiza in an 1837 publication,[7] and George Gray wrote Entomyza in 1840.[8]

The blue-faced honeyeater is generally held to be the only member of the genus, although its plumage suggests an affinity with honeyeaters of the genus Melithreptus. It has been classified in that genus by Glen Storr,[9][10] although others felt it more closely related to wattlebirds (Anthochaera) or miners (Manorina).[11] A 2004 molecular study has resolved that it is closely related to Melithreptus after all.[12] Molecular clock estimates indicate that the blue-faced honeyeater diverged from the Melithreptus honeyeaters somewhere between 12.8 and 6.4 million years ago, in the Miocene epoch. It differs from them in its much larger size, brighter plumage, more gregarious nature, and larger patch of bare facial skin.[13]

Molecular analysis has shown honeyeaters to be related to the Pardalotidae (pardalotes), Acanthizidae (Australian warblers, scrubwrens, thornbills, etc.), and the Maluridae (Australian fairy-wrens) in the large superfamily Meliphagoidea.[14]

"Blue-faced honeyeater" has been designated as the official common name for the species by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC).[15] Early naturalist George Shaw had called it the blue-faced honey-sucker in 1826.[16] Other common names include white-quilled honeyeater and blue-eye.[17] Its propensity for feeding on the flowers and fruit of bananas in north Queensland has given it the common name of banana-bird.[17] A local name from Mackay in central Queensland is pandanus-bird, as it is always found around Pandanus palms there.[18] It is called morning-bird from its dawn calls before other birds of the bush. Gympie is a Queensland bushman's term.[19] Thomas Watling noted a local indigenous name was der-ro-gang.[3] John Hunter recorded the term gugurruk (pron. "co-gurrock"), but the term was also applied to the black-shouldered kite (Elanus axillaris).[20] It is called (minha) yeewi in Pakanh, where minha is a qualifier meaning 'meat' or 'animal', and (inh-)ewelmb in Uw Oykangand and Uw Olkola, where inh- is a qualifier meaning 'meat' or 'animal', in three aboriginal languages of central Cape York Peninsula[21]

Three subspecies are recognised:

- E. c. albipennis was described by John Gould in 1841[22] and is found in north Queensland, west through the Gulf of Carpentaria, in the Top End of the Northern Territory, and across into the Kimberley region of Western Australia. It has white on the wings and a discontinuous stripe on the nape. The wing-patch is pure white in the western part of its range, and is more cream towards the east.[23] It has a longer bill and shorter tail than the nominate race. The blue-faced honeyeater also decreases in size with decreasing latitude, consistent with Bergmann's rule.[24] Molecular work supports the current classification of this subspecies as distinct from the nominate subspecies cyanotis.[13]

- E. c. cyanotis, the nominate form, is found from Cape York Peninsula south through Queensland and New South Wales, into the Riverina region, Victoria, and southeastern South Australia.[17]

- E. c. griseigularis is found in southwestern New Guinea and Cape York, and was described in 1909 by Dutch naturalist Eduard van Oort.[25] It is much smaller than the other subspecies. The original name for this subspecies was harteri, but the type specimen, collected in Cooktown, was found to be an intergrade form. The new type was collected from Merauke. This subspecies intergrades with cyanotis at the base of the Cape York Peninsula, and the zone of intermediate forms is narrow.[24] The white wing-patch is larger than that of cyanotis and smaller than that of albipennis.[23] Only one bird (from Cape York) of this subspecies was sampled in a molecular study, and it was shown to be genetically close to cyanotis.[13]

Description

editA large honeyeater ranging from 26 to 32 cm (10 to 12.5 in) and averaging 29.5 cm (11.6 in) in length. The adult blue-faced honeyeater has a wingspan of 44 cm (17.5 in) and weighs around 105 g (3.7 oz).[17] In general shape, it has broad wings with rounded tips and a medium squarish tail. The sturdy, slightly downcurved bill is shorter than the skull, and measures 3 to 3.5 cm (1.2 to 1.4 in) in length.[24] It is easily recognised by the bare blue skin around its eyes. The head and throat are otherwise predominantly blackish with a white stripe around the nape and another from the cheek. The upperparts, including mantle, back and wings, are a golden-olive colour, and the margins of the primary and secondary coverts a darker olive-brown, while the underparts are white. Juveniles that have just fledged have grey head, chin, and central parts of their breasts, with brown upperparts, and otherwise white underparts. After their next moult, they more closely resemble adults and have similar plumage, but are distinguished by their facial patches.[26] The bare facial skin of birds just fledged is yellow, sometimes with a small patch of blue in front of the eyes, while the skin of birds six months and older has usually become more greenish, and turns darker blue beneath the eye, before assuming the adult blue facial patch by around 16 months of age.[24] The blue-faced honeyeater begins its moult in October or November, starting with its primary flight feathers, replacing them by February. It replaces its body feathers anywhere from December to June, and tail feathers between December and July.[26] 422 blue-faced honeyeaters have been banded between 1953 and 1997 to monitor movements and longevity. Of these, 109 were eventually recovered, 107 of which were within 10 km (6.2 mi) of their point of banding.[27] The record for longevity was a bird banded in May 1990 in Kingaroy in central Queensland, which was found dead on a road after 8 years and 3.5 months in September 1998, around 2 km (1.2 mi) away.[28]

The blue-faced honeyeater produces a variety of calls, including a piping call around half an hour before dawn, variously described as ki-owt,[29] woik, queet, peet, or weet. Through the day, it makes squeaking noises while flying, and harsh squawks when mobbing. Its calls have been likened to those of the yellow-throated miner (Manorina flavigula), but are deeper. Blue-faced honeyeaters make a soft chirping around nestlings and family members.[30]

A distinctive bird, the blue-faced honeyeater differs in coloration from the duller-plumaged friarbirds, miners and wattlebirds, and it is much larger than the similarly coloured Melithreptus honeyeaters. Subspecies albipennis, with its white wing-patch, has been likened to a khaki-backed butcherbird in flight.[17]

Distribution and habitat

editThe blue-faced honeyeater is found from the Kimberleys in northwestern Australia eastwards across the Top End and into Queensland, where it is found from Cape York south across the eastern and central parts of the state, roughly east of a line connecting Karumba, Blackall, Cunnamulla and Currawinya National Park.[31] It has a patchy distribution in New South Wales, occurring in the Northern Rivers and Northern Tablelands regions, and along the coast south to Nambucca Heads.A single bird was observed in Collaroy on the northern beaches of Sydney on 22/9/24. To the south, it is generally absent from the Central and South Coast, and is instead found west of the Great Divide across the South West Slopes and Riverina to the Murray River. It is common in northern Victoria and reaches Bordertown in southeastern South Australia, its range continuing along the Murray. It is also found in the Grampians region, particularly in the vicinity of Stawell, Ararat and St Arnaud, with rare reports from southwestern Victoria. The species occasionally reaches Adelaide, and there is a single record from the Eyre Peninsula.[32] The altitude ranges from sea level to around 850 m (2,790 ft), or rarely 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[31]

In New Guinea, it is found from Merauke in the far southeast of Indonesia's Papua province and east across the Trans-Fly region of southwestern Papua New Guinea.[31] It has also been recorded from the Aru Islands.[33]

The blue-faced honeyeater appears to be generally sedentary within its range, especially in much of the Northern Territory, Queensland and New South Wales. However, in many places (generally south of the Tropic of Capricorn), populations may be present or absent at different times of the year, although this appears to result from nomadic, rather than seasonal, migratory movements.[27] Around Wellington in central New South Wales, birds were recorded over winter months,[34] and were more common in autumn around the Talbragar River.[35] Birds were present all year round near Inverell in northern New South Wales, but noted to be flying eastwards from January to May, and westwards in June and July.[36] In Jandowae in southeastern Queensland, birds were regularly recorded flying north and east from March to June, and returning south and west in July and August, and were absent from the area in spring and summer.[37]

They live throughout rainforest, dry sclerophyll (Eucalyptus) forest, open woodland, Pandanus thickets, paperbarks, mangroves, watercourses, and wetter areas of semi-arid regions, as well as parks, gardens, and golf courses in urban areas.[17] The understory in eucalypt-dominated woodland, where the blue-faced honeyeater is found, is most commonly composed of grasses, such as Triodia, but sometimes it is made up of shrubs or small trees, such as grevilleas, paperbarks, wattles, Cooktown ironwood (Erythrophleum chlorostachys) or billygoat plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana).[31] One study in Kakadu National Park found that blue-faced honeyeaters inhabited mixed stands of eucalypts and Pandanus, but were missing from pure stands of either plant.[38]

Behaviour

editThe social organisation of the blue-faced honeyeater has been little studied to date. Encountered in pairs, family groups or small flocks, blue-faced honeyeaters sometimes associate with groups of yellow-throated miners (Manorina flavigula). They mob potential threats, such as goshawks (Accipiter spp.), rufous owls (Ninox rufa), and Pacific koels (Eudynamys orientalis). There is some evidence of cooperative breeding, with some breeding pairs recorded with one or more helper birds. Parents will dive at and harass intruders to drive them away from nest sites, including dogs, owls, goannas,[30] and even a nankeen night-heron (Nycticorax caledonicus).[39] A study published in 2004 of remnant patches of forest in central Queensland, an area largely cleared for agriculture, showed a reduced avian species diversity in areas frequented by blue-faced honeyeaters or noisy miners. This effect was more marked in smaller patches. The study concluded that conserved patches of woodland containing the two aggressive species should be larger than 20 ha (44 acres) to preserve diversity.[40]

Social birds, blue-faced honeyeaters can be noisy when they congregate.[30] When feeding in groups, birds seem to keep in contact with each other by soft chirping calls.[30] In Mackay, a bird would fly up 10 or 12 metres (33 or 39 ft) above the treetops calling excitedly to its flock, which would follow and fly around in what was likened to an aerial corroboree, seemingly at play.[18] A single bird was recorded aping and playing with an immature Australian magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen) in Proserpine, Queensland.[30] The blue-faced honeyeater has been reported to be fond of bathing;[41] a flock of 15–20 birds was observed diving into pools one bird at a time, while others were perched in surrounding treetops preening.[42]

The parasite Anoncotaenia globata (a worldwide species not otherwise recorded from Australia) was isolated from a blue-faced honeyeater collected in North Queensland in 1916.[43] The habroneme nematode, Cyrnea (Procyrnea) spirali, has also been isolated from this among other honeyeater species.[44] The nasal mite, Ptilonyssus philemoni, has been isolated from the noisy friarbird (Philemon corniculatus) and blue-faced honeyeater.[45]

Breeding

editThe blue-faced honeyeater probably breeds throughout its range.[32] The breeding season is from June to January, with one or two broods raised during this time. The nest is an untidy, deep bowl of sticks and bits of bark in the fork of a tree, Staghorn or bird's nest ferns,[46] or grasstree.[30] Pandanus palms are a popular nest site in Mackay.[18] They often renovate and use the old nests of other species, most commonly the grey-crowned babbler (Pomatostomus temporalis), but also the chestnut-crowned babbler (P. ruficeps), other honeyeaters, including noisy (Philemon corniculatus), little (P. citreogularis) and silver-crowned friarbirds (P. argenticeps), the noisy miner (Manorina melanocephala) and the red wattlebird (Anthochaera carunculata), and artamids, such as the Australian magpie and butcherbird species, and even the magpie-lark.[30] In Coen, an old babbler nest in a paperbark (Melaleuca), which had been lined with messmate bark, had been occupied by blue-faced honeyeaters and re-lined with strips of paperbark.[47] Two or, rarely, three eggs are laid, 22 × 32 mm (1 × 1⅓ in) and buff-pink splotched with red-brown or purplish colours.[46] The female alone incubates the eggs over a period of 16 or 17 days.[48]

Like those of all passerines, the chicks are altricial; they are born blind and covered only by sparse tufts of brown down on their backs, shoulders and parts of the wings. By four days they open their eyes, and pin feathers emerge from their wings on day six, and the rest of the body on days seven and eight.[48] Both parents feed the young, and are sometimes assisted by helper birds.[30] The Pacific koel (Eudynamys orientalis) and pallid cuckoo (Cuculus pallidus) have been recorded as brood parasites of the blue-faced honeyeater, and the laughing kookaburra recorded as preying on broods.[49]

Feeding

editThe blue-faced honeyeater generally forages in the branches and foliage of trees, in small groups of up to seven birds. Occasionally, larger flocks of up to 30 individuals have been reported,[41] and the species has been encountered in a mixed-species foraging flock with the little friarbird (Philemon citreogularis).[39] The bulk of their diet consists of insects, including cockroaches, termites, grasshoppers, bugs such as lerps, scale (Coccidae) and shield bugs (Pentatomidae), beetles such as bark beetles, chafers (subfamily Melolonthinae), click beetles (genus Demetrida), darkling beetles (genera Chalcopteroides and Homotrysis), leaf beetles (genus Paropsis), ladybirds of the genus Scymnus, weevils such as the pinhole borer (Platypus australis), and members of the genera Mandalotus, Polyphrades and Prypnus, as well as flies, moths, bees, ants, and spiders.[50] Blue-faced honeyeaters have been reported preying on small lizards.[51] Prey are caught mostly by sallying, although birds also probe and glean.[51] In Kakadu National Park, birds prefer to hunt prey between the leaf bases of the screw palm (Pandanus spiralis).[38]

The remainder of their diet is made up of plant material, such as pollen, berries, and nectar, from such species as grasstrees (Xanthorrhoea) and scarlet gum (Eucalyptus phoenicea), and from cultivated crops, such as bananas or particularly grapes.[50] In general, birds prefer feeding at cup-shaped sources, such as flowers of the Darwin woollybutt (Eucalyptus miniata), Darwin stringybark (E. tetrodonta) and long-fruited bloodwood (Corymbia polycarpa), followed by brush-shaped inflorescences, such as banksias or melaleucas, gullet-shaped inflorescences such as grevilleas, with others less often selected.[51]

Usually very inquisitive and friendly birds, they will often invade a campsite, searching for edible items, including fruit, insects, and remnants from containers of jam or honey, and milk is particularly favoured.[19] Parent birds feed the young on insects, fruit and nectar, and have been recorded regurgitating milk to them as well.[19]

Aviculture

editKeeping blue-faced honeyeaters in an aviary in New South Wales requires a Class 2 Licence. Applicants must show they have appropriate housing, and at least two years' experience of keeping birds.[52] Blue-faced honeyeaters are exhibited at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago,[53] Philadelphia Zoo,[54] Columbus Zoo and Aquarium (Ohio), Birmingham Zoo (Alabama), and Tracy Aviary (Utah),[55] Woodland Park Zoo (Seattle)[56] Children's Zoo at Celebration Square (Michigan) in the United States,[57] Marwell Zoo in England, Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland and Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia.[58]

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Entomyzon cyanotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T103685011A93968048. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T103685011A93968048.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Latham, John (1801). Supplementum Indicis Ornithologici, sive Systematis Ornithologiae (in Latin). London: G. Leigh, J. & S. Sotheby. pp. 29, 34, 42.

- ^ a b Sharpe, Richard Bowdler (1904). The history of the collections contained in the natural history departments of the British Museum. London: British Museum. p. 126.

- ^ "Blue-cheeked Bee Eater", native name "Der-ro-gang". First Fleet Artwork Collection. The Natural History Museum, London. 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ Swainson, William (1825). "Art. LX. On The Characters and Natural Affinities of several New Birds from Australasia, including some Observations of the Columbidae". Zoological Journal. 1: 463–484.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980) [1871]. A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 397, 507. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ Swainson, William (1837). "On the Natural History and Classification of Birds". In Lardner, D. (ed.). The Cabinet Cyclopaedia. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman and John Taylor. p. 328.

- ^ Gray, George Robert (1840). A List of the Genera of Birds, with an indication of the typical species of each genus. London: R. & J.E. Taylor. p. 21.

- ^ Storr, Glen Milton (1977). Birds of the Northern Territory. Fremantle, Western Australia: Western Australian Museum Special Publication No. 7. ISBN 0-7244-6281-3.

- ^ Storr, Glen Milton (1984). Revised List of Queensland birds. Perth, Western Australia: Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 19. ISBN 0-7244-8765-4.

- ^ Schodde, Richard; Mason, Ian J. (1999). The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines. A taxonomic and zoogeographic atlas of the biodiversity of birds of Australia and its territories. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 273–75. ISBN 0-643-06456-7.

- ^ Driskell, Amy C.; Christidis, Les (2004). "Phylogeny and evolution of the Australo-Papuan honeyeaters (Passeriformes, Meliphagidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31 (3): 943–60. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.017. PMID 15120392.

- ^ a b c Toon, Alicia; Hughes, Jane M.; Joseph, Leo (2010). "Multilocus analysis of honeyeaters (Aves: Meliphagidae) highlights spatio-temporal heterogeneity in the influence of biogeographic barriers in the Australian monsoonal zone". Molecular Ecology. 19 (14): 2980–94. Bibcode:2010MolEc..19.2980T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04730.x. PMID 20609078. S2CID 25346288.

- ^ Barker, F. Keith; Cibois, Alice; Schikler, Peter; Feinstein, Julie; Cracraft, Joel (2004). "Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (30): 11040–45. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111040B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101. PMC 503738. PMID 15263073.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2021). "Honeyeaters". World Bird List Version 11.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Shaw, George; Stephens, James Francis (1826). General zoology: or Systematic natural history. Vol. 14, Part 1. G. Kearsley. p. 260.

- ^ a b c d e f Higgins, p. 598.

- ^ a b c Harvey, William G.; Harvey, Robert C. (1919). "Bird Notes from Mackay, Queensland". Emu. 19 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1071/MU919034.

- ^ a b c Lord, E. A. R. (1950). "Notes on the Blue-faced Honeyeater". Emu. 50 (2): 100–01. Bibcode:1950EmuAO..50..100L. doi:10.1071/MU950100.

- ^ Troy, Jakelin (1993). The Sydney language. Canberra: Jakelin Troy. p. 53. ISBN 0-646-11015-2.

- ^ Hamilton, Philip (1997). "blue-faced honeyeater, Entomyzon cyanotis". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Gould, John (1841). "Entomyza albipennis". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (8): 169. Issue is inscribed 1840 but published in 1841.

- ^ a b Higgins, p. 608.

- ^ a b c d Higgins, p. 607.

- ^ Van Oort; Eduard D. (1909). "Birds from south western and southern New Guinea". Nova Guinea: Résultats de l'Expédition Scientifique Néerlandaise a la Nouvelle-Guinée. 9: 51–107 [97].

- ^ a b Higgins, p. 606.

- ^ a b Higgins, p. 601.

- ^ "ABBBS Database Search: Entomyzon cyanotis (Blue-faced Honeyeater)". Australian Bird & Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS). Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia. 13 April 2007.

- ^ Simpson, Ken; Day, Nicolas; Trusler, Peter (1993). Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Ringwood, Victoria: Viking O'Neil. p. 392. ISBN 0-670-90478-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Higgins, p. 604.

- ^ a b c d Higgins, p. 599.

- ^ a b Higgins, p. 600.

- ^ Gannon, Gilbert Roscoe (1962). "Distribution of Australian Honeyeaters". Emu. 62 (3): 145–66. Bibcode:1962EmuAO..62..145G. doi:10.1071/MU962145.

- ^ Althofer, George W. (1934). "Birds of Wellington District". Emu. 34 (2): 105–12. doi:10.1071/MU934105b.

- ^ Austin, Thomas B. (1907). "Notes on Birds from Talbragar River, New South Wales". Emu. 7 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1071/MU907028.

- ^ Baldwin, Merle (1975). "Birds of Inverell District". Emu. 75 (2): 113–20. Bibcode:1975EmuAO..75..113B. doi:10.1071/MU9750113.

- ^ Nielsen, Lloyd (1966). "Migration of the Blue-faced Honeyeater". Emu. 65 (4): 305–09. Bibcode:1966EmuAO..65..305N. doi:10.1071/MU965305.

- ^ a b Verbeek, Nicholas A.M.; Braithwaite, Richard W; Boasson, Rosalinda (1993). "The Importance of Pandanus spiralis to Birds". Emu. 93 (1): 53–58. Bibcode:1993EmuAO..93...53V. doi:10.1071/MU9930053.

- ^ a b Wolstenholme, H. (1925). "Notes on the Birds observed during the Queensland Congress and Camp-out, 1924: Pt II". Emu. 24 (4): 243–251. doi:10.1071/MU924243.

- ^ Chan, Ken (2004). "Effect of patch size and bird aggression on bird species richness: A community-based project in tropical/subtropical eucalypt woodland". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 111: 1–11. ISSN 0080-469X.

- ^ a b Longmore, N. Wayne (1978). "Avifauna of the Rockhampton area, Queensland". Sunbird. 9: 25–53.

- ^ Rix, Cecil E. (1970). "Birds of the Northern Territory". South Australian Ornithologist. 25: 147–91.

- ^ Schmidt, Gerald D. (1972). "Cyclophyllidean Cestodes of Australian Birds, with Three New Species". The Journal of Parasitology. 58 (6): 1085–94. doi:10.2307/3278142. JSTOR 3278142. PMID 4641876.

- ^ Mawson, Patricia M. (1968). "Habronematidae (Nematoda – Spiruridae) from Australian Birds, with Three New Species". Parasitology. 58 (4): 745–67. doi:10.1017/S0031182000069559. S2CID 86403736.

- ^ Domrow, Robert (1964). "Fourteen species of Ptilonyssus from Australian birds (Acarina, Laelapidae)". Acarologia. 6: 595–623.

- ^ a b Beruldsen, Gordon (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills, Qld: self. p. 314. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- ^ White, Henry J. (1922). "An abnormal clutch of Blue-face Honey Eater's eggs (Entomyza cyanotis harterti)". Emu. 22 (1): 3. Bibcode:1922EmuAO..22....3W. doi:10.1071/mu922003.

- ^ a b Atchison, N. (1992). "Breeding blue-faced honeyeaters at Taronga Zoo". Australian Aviculture. 46: 29–35.

- ^ Higgins, p. 605.

- ^ a b Barker, Robin Dale; Vestjens, Wilhelmus Jacobus Maria (1984). The Food of Australian Birds: Volume 2 – Passerines. Melbourne University Press. pp. 195–96. ISBN 0-643-05006-X.

- ^ a b c Higgins, p. 602.

- ^ Wildlife Licensing Section; Biodiversity Management Unit (October 2003). "New South Wales Bird Keeping Licence: Species Lists (October 2003)" (PDF). National Parks and Wildlife Service, New South Wales Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2011.

- ^ "Blue-faced Honeyeater". Lincoln Park Zoo website. Chicago, Illinois: Lincoln Park Zoo. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "McNeil Avian Center". Philadelphia Zoo website. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia Zoo. 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Tracy Aviary - Expedition Kea". Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Animals at Woodland Park Zoo - Woodland Park Zoo Seattle WA". www.zoo.org. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "List of Animals". Birmingham Zoo website. Birmingham Zoo, Inc. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Animals at Taronga Zoo". Taronga Zoo website. Mosman, New South Wales. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010.

Cited text

edit- Higgins, Peter J.; Peter, Jeffrey M.; Steele, W. K., eds. (2001). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 5: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553258-9.

External links

edit- Blue-faced honeyeater videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Sound recording of blue-faced honeyeater on Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology's Macaulay Library website

- Meliphagoidea – Highlighting relationships of Meliphagidae on Tree of Life Web Project