Boii is an extinct genus of microsaur within the family Tuditanidae.[1] It was found in Carboniferous coal from mines near the community of Kounov in the Czech Republic. The only remains of the genus consist of a crushed skull, shoulder girdle bones, and scales, which were similar to microsaurian elements originally referred to Asaphestera. Boii can be characterized by its heavily sculptured skull, thin ventral plate of the clavicles, and a larger number of fangs on the roof of the mouth.[2] For many years the type and only known species, Boii crassidens, was considered to be a species of Sparodus,[3] until 1966 when Robert Carroll assigned it to its own genus.[4]

| Boii Temporal range: Carboniferous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

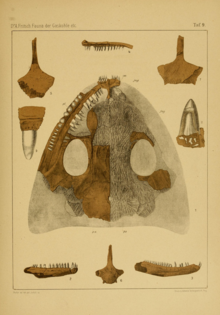

| The crushed skull of Boii, showing impressions (grey) and the underside of preserved bones (yellow) illustrated along with other tetrapod fragments by Frič (1883) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Microsauria |

| Family: | †Tuditanidae |

| Genus: | †Boii Carroll, 1966 |

| Type species | |

| Boii crassidens Frič, 1876

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

History

editThe specimen now designated as Boii crassidens was first described by Antonin Frič, one of the most notable paleontologists in the late 19th century region of Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic). Frič made many contributions to knowledge of Carboniferous tetrapods during his lifetime, including a particular article published in "Sitzungsberichte der königlichen Böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Prague", the most notable bohemian scientific journal of its day. The article, which was published in 1876 within volume 1875 of the journal, was a list of Carboniferous animals he and his associates recently discovered at gaskohle (bituminous coal) mines near the localities of Nýřany and Kounová. His list included short preliminary descriptions for many new genera and species of tetrapods, including Microbrachis, Branchiosaurus, Hyloplesion (at that time called Stelliosaurus), and Sparodus.[5]

Most of the "Saurier" (reptiles, amphibians, or other tetrapods) he discussed in the article hailed from the Nýřany mines, with only two diagnostic examples found within the Kounová mines. One of these was a supposed amphibian he designated as "Labyrinthodon" shwarzenbergii, which is now known to not be an amphibian at all, but rather an early synapsid named Macromerion.[6] The other specimen, which is now known as Boii crassidens, he named Batrachocephalus crassidens. This specimen consisted of a crushed skull, preserved on a slab and counterslab of coal. Jaw bones, scales, and shoulder girdle elements were preserved on the slabs as well.[5] It is currently held at the National Museum in Prague, with the designation ČGH 83.[4]

This article was only a preliminary review of the creatures Frič and his associates discovered. A more elaborate description was published in 1883 as part of a personal monograph focusing solely on the creatures discovered at these mines. This description renamed Batrachocephalus crassidens to Sparodus crassidens, as the genus name 'Batrachocephalus' was already taken by Batrachocephalus mino, an Indonesian species of catfish. Frič also assigned an isolated maxilla (upper jaw bone) with designation ČGH 124 to this species, although it was quite a bit larger than the maxilla of the crushed skull.[3][4]

In a 1966 review of microsaurs published by Robert Carroll, "Sparodus" crassidens was not found to be a member of the genus Sparodus. Instead, it was re-evaluated as belonging to a family of early microsaurs known as the Tuditanidae. This prompted Carroll to create a new genus name for the specimens previously considered to belong to "Sparodus" crassidens. The new name he found was Boii crassidens, named after the Boii tribe which inhabited the area of Bohemia during the time of the Roman Republic.[4]

Description

editSkull

editThe crushed skull was pressed between two plates of coal which preserved the outer impressions of bones on both the underside and upper side of the specimen. Although not all of the bones were preserved, the outer impressions helped to reconstruct the structure of these missing bones. The impressions were used to reconstruct the skull and lower jaws, while the skull itself (which preserved the palate better than the impressions) was removed and encased in Canada balsam. The skull was initially believed to have been stout, approximately as long as it was wide. This 'frog-like' skull is responsible for the original genus name "Batrachocephalus", which is Greek for "frog head".[5] However, later reconstructions from Robert Carroll have interpreted this wide shape as a result of the crushing the skull experienced, with the skull actually being narrow and somewhat triangular, more similar in shape to that of a lizard rather than a frog.[2]

The orbits (eye holes) are roughly midway down the length of the skull. Unlike the fairly smooth skulls of most microsaurs, the skull of Boii is covered with numerous grooves and ridges which radiate from the middle of their respective bones. The maxillary and premaxillary bones forming the edge of the snout contained many conical teeth, about 30 per each side of the upper jaw. This number is somewhat larger than that of the eponymous tuditanid Tuditanus. These marginal (edge) teeth in general are slightly larger towards the front of the skull, although only to a small extent.[4]

The palate (roof of the mouth) also possesses teeth. The palatine bones, positioned right next to the maxillae, possess a fair number of teeth. The most notable assortment of palatal teeth are a bundle of large fangs preserved midway down the skull. Large palatal fangs are also shared by Sparodus, explaining how Boii crassidens was once considered to be part of that genus. Frič (1883) considered these fangs to have grown out of the vomers (from the front of the skull) or possibly the parasphenoid (from the back of the skull),[3] but Carroll (1966) reconstructed the fangs as being part of the long pterygoid bones, which were originally reported as being toothless.[4][2] The dentaries (main bones of the lower jaws) are also preserved and covered with teeth similar to those of the upper jaws. A row of small pits run from the symphysis (chin) along the upper portion of the outer face of the bones.[4]

Other bones

editSome bones of the shoulder girdle are known. A pair of V-shaped bones are preserved behind the skull, which Frič (1883) identified as coracoids. However, research by Carroll has indicated that microsaurs did not possess coracoid bones, and that the bones identified by Frič were actually clavicles. Clavicles possess two blade-like regions pointing away from each other at right angles when seen from the front. The lower regions point inwards and laying along the chest and the upper regions point upwards along the sides of the body. The lower regions (a.k.a. ventral plates) of Boii's clavicles are very thin, akin to those of a reptile.[2] As typical for many tetrapods, Boii also possessed an interclavicle which was positioned behind the clavicles at the center of the chest. However, the only remnant of this bone in the specimen is a large yet indistinct impression. A single arm bone was also present on the specimen, although paleontologists disagree whether it was a humerus (according to Frič, 1883)[3] or a radius or ulna (according to Carroll, 1966).[4]

Boii possessed large scales, as preserved in the only known specimen. The scales of the back of the animal were tile-like with rounded corners. They tightly overlapped in alternating rows, and each possessed a bulging rear edge. The scales of the belly of the animal were also overlapping. However, these belly scales were wider than the back scales, and their rows were stacked so frequently that only a small portion of each individual scale is visible.[3]

Classification

editFrič (1883) considered Boii crassidens to be a member of the family Branchiosauridae, along with other species of Sparodus.[3] Branchiosaurids, a group of small gilled temnospondyls, are now believed to be only distant relatives of Sparodus and Boii. In 1894, John William Dawson listed the three Sparodus species as microsaurs rather than branchiosaurids. He did not explicitly note each individual species (instead clumping them as "Sparodus sp."), because he was unsure whether they were all valid members of the same genus.[7]

Dawson's suspicions were rectified in 1966, when Carroll split Boii crassidens off of Sparodus. The skull structure of Boii was considered to be very similar to that Asaphestera (which itself was similar to Tuditanus), so he placed Boii along with Asaphestera in Tuditanidae. Tuditanids were basal microsaurs, which did not evolve the unusual adaptations of more advanced families of microsaurs. They were terrestrial, lizard-like creatures with well-developed legs and jaw joints set about as far back as the neck joint. Although Boii crassidens was quite old by microsaur standards, it is one of the last known species of tuditanids.[2] Carroll (1966) suggested that it may have been descended from Asaphestera, supposedly one of the earliest known microsaurs to have evolved.[4] However, as of 2020 Asaphestera has been recognized as a chimeric taxon, based on specimens of a potential eothyridid along with a newly-named microsaur, Steenerpeton.[8]

External links

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "†Boii Carroll 1966". Paleobiology Database. Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Carroll, Robert L.; Gaskill, Pamela (1978). The Order Microsauria. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871691262.

- ^ a b c d e f Frič, Antonin (1883). "Fauna der Gaskohle und der Kalksteine der Permformation Böhmens". Self-published. 1 (3): 136–146.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carroll, Robert (January 1966). "Microsaurs from the Westphalian B of Joggins, Nova Scotia". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 177 (1): 63–97. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1966.tb00952.x. ISSN 0370-0461.

- ^ a b c Frič, Antonin (March 19, 1876). "Über die Fauna der Gaskohle des Pilsner und Rakonitzer Beckens". Sitzungsberichte der Königlichen Böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Prague. 1875: 70–78.

- ^ Fröbisch, Jörg; Schoch, Rainer R.; Müller, Johannes; Schindler, Thomas; Schweiss, Dieter (2011). "A new basal sphenacodontid synapsid from the Late Carboniferous of the Saar-Nahe Basin, Germany" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (1): 113–120. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0039. S2CID 45410472.

- ^ Dawson, Sir John William (23 May 1894). "Synopsis of the Air breathing Animals of the Palæozoic in Canada, up to 1894". Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. 4: 71–88.

- ^ Mann, Arjan; Gee, Bryan M.; Pardo, Jason D.; Marjanović, David; Adams, Gabrielle R.; Calthorpe, Ami S.; Maddin, Hillary C.; Anderson, Jason S. (5 May 2020). Sansom, Robert (ed.). "Reassessment of historic 'microsaurs' from Joggins, Nova Scotia, reveals hidden diversity in the earliest amniote ecosystem". Papers in Palaeontology. 6 (4). Wiley: 605–625. Bibcode:2020PPal....6..605M. doi:10.1002/spp2.1316. ISSN 2056-2802. S2CID 218925814.