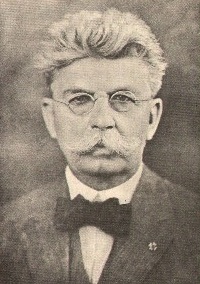

Francis Marion Smith (February 2, 1846 – August 27, 1931) was an American miner, business magnate and civic builder in the Mojave Desert, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Oakland, California. He was known nationally and internationally as "Borax Smith" and "The Borax King", as his company produced the popular 20-Mule-Team Borax brand of household cleaner.[1][2]

Francis Marion Smith | |

|---|---|

Francis Marion "Borax" Smith | |

| Born | February 2, 1846 |

| Died | August 27, 1931 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | Mining businessman |

| Known for | Borax King, founder of Pacific Coast Borax Company |

| Spouses | Mary Rebecca Thompson Wright

(m. 1875)Evelyn Kate Ellis (m. 1906) |

Frank Smith created the Key System, an interurban private transit system, which operated in Oakland and the East Bay with a terminus in the San Francisco Transbay Terminal.

Early life

editFrancis Marion Smith was born in Richmond, Wisconsin in 1846. He went to public schools and graduated from Milton Academy in Milton, Wisconsin.

Early mining career

editAt the age of 21, he left Wisconsin to prospect for mineral wealth in the American West, starting in Nevada.[4]

In 1872, while contracting to provide firewood to a small borax operation at nearby Columbus Marsh, Smith discovered a rich supply of ulexite at Teels Marsh in Mineral County, Nevada, east of Mono Lake, near the town he would found ten years later, Marietta, Nevada, while looking westward from the upper slopes of Miller Mountain where the only nearby trees were growing.[5] Eventually, to satisfy his curiosity, Smith and two assistants visited Teels Marsh and collected samples that proved to assay higher than any known sources for borate.[5] Returning to Teels Marsh, Smith and his helpers staked claims and started a company with his brother Julius Smith, and established a borax works at the edge of the marsh to concentrate the borax crystals and separate them from dirt and other impurities.[5] Smith had a house in Tonopah, Nevada.[6]

In 1877, Scientific American reported that the Smith Brothers shipped their product in a 30-ton load using two large wagons with a third wagon for food and water drawn by a 24-mule team for 160 miles (260 km) across the Great Basin Desert from Marietta to the nearest Central Pacific Railroad siding in Wadsworth, Nevada.[7]

The Borax King

editDeath Valley

editSmith then acquired properties at Columbus Marsh and Fish Lake. In 1884, Smith bought out his brother. While reduced operations continued at Teels, Smith now focused his energies and borax mining in Death Valley and at the 20 Mule Team Canyon mine in the Amargosa Range to the east. In 1890, upon William Tell Coleman's Harmony Borax Works financial overextension, he acquired Coleman's borax works and holdings in western Nevada, the Death Valley region, and in the Calico Mountains near Yermo, California. Smith then consolidated them with his own holdings to form the Pacific Coast Borax Company in 1890.

Smith's Pacific Coast Borax Company then established and aggressively promoted the 20-Mule-Team Borax brand and trademark, which was named after the Twenty Mule Teams that Coleman had used, from 1883 to 1889, to transport borax out of Death Valley to the closest railroad in Mojave, California (and as Smith himself had developed even earlier at his borax works in Nevada - see above). The idea came from Smith's advertising manager, Stephen Mather, later owner of Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company, and in 1916 appointed the first Chief of the new National Park Service.

Other mines

editActivity at Harmony Borax Works in Death Valley ceased with the development of the richer Colemanite borax deposits at Borate in the Calico Mountains, which were discovered in 1882 and began operations in 1890, where they continued until 1907. Initial hauling to the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad was done again by the 20 mule teams, but were retired as soon as Smith completed the 12-mile (19 km) long Borate and Daggett Railroad.

When the deposits at Borate neared depletion, work began near Death Valley Junction to develop nearby claims at what became known as the Lila C Mine in 1907. Again, long mule teams were used in the early years while Smith constructed the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad connecting with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad across the Mojave River and Kelso Dunes at Ludlow, California.

In 1899, Smith had joined forces with Richard C. Baker to form the Borax Consolidated, Ltd.[8] Together, they formed a multinational mining conglomerate, in which Smith had the controlling interest. Baker expanded the company's foreign acquisitions in Italy, Turkey, and South America and was largely responsible for capitally financing the corporation's expansion.[9]

While operating at Borate, Smith purchased the Boric acid mineral rights at the "Suckow claims" at Boron, California between Barstow and Mojave and east of present-day Edwards Air Force Base. The incorporation of Borax Consolidated, Ltd. included the Sterling Borax Company and the Suckow Property.[8] Though never developed by Smith's Pacific Coast Borax Company, his corporate successors have obtained all their borax minerals from the Suckow claims for more than 75 years, and estimate remaining deposits will last for nearly as long. It is now California's largest open-pit mine, which is also the largest borax mine in the world, and where today almost half of the world's borates are currently mined.[10][11]

Last mining

editIn 1913, Smith became financially overextended and had to turn over his assets to creditors who refused to extend new loans. After winning a lawsuit to protect his wife's interest in a silver mine in Tonopah, Nevada, he acquired mineral rights to a large section of Searles Lake in the Searles Valley over the Panamint Range from Death Valley, in northern San Bernardino County, California. However, finding a profitable way to convert the extensive lake brines into borax and other important commercial mineral salts products proved elusive for roughly a decade.

In the meantime, he outbid the new owners of his company for the rights to a rich borax discovery in Nevada's Muddy Mountains, near Callville Wash, north of present-day Lake Mead and south of Muddy Mountain. He called his operations there the West End Chemical Company and the claim the Anniversary Mine as the claims were acquired on the anniversary of his marriage to his second wife. The profits from this claim provided the capital to develop the Searles Lake deposits. His first efforts in 1918 to recover borax were unsuccessful. However, a young chemist, Henry Hellmers, that he hired to work at the Anniversary Mine discovered a profitable process for refining the lake brines into marketable products and by 1926 had a plant operating at Searles Lake. In 1927 the plant was expanded to also produce soda ash.[12] The West End Chemical Company plant in Searles Valley used the Trona Railway, a Short-line railroad, to ship the products to the Union Pacific Railroad connection at Searles, California. The Trona Railway was founded by the American Trona Company in 1913. The operation of the railroad is now under Searles Valley Minerals. Note: There is no evidence or reason to believe that Francis Marion Smith was involved in the building of the Trona Railway.

Oakland years

editSmith married Mary Rebecca Thompson Wright (1846-1905, known as Mollie) in 1875. After living in Nevada for a few years they settled in Oakland, California in 1881.[13] Following Mollie's death in 1905 at age 59, he remarried in 1906 to Evelyn Kate Ellis (1877-1957).

In 1882 Smith began accumulating parcels of land in Oakland that became the estate called Arbor Villa.[14] He and Mollie moved into Oak Hall, the mansion they had built on the estate, in about 1895.[15] This residence was furnished with a pipe organ built by the Farrand and Votey Organ Co. of Detroit as their Opus 852 in 1898.[16]

In 1892, he began building a summer estate in Shelter Island, New York, named Pres DeLeau, within his wife's geo-social circle.[17]

In 1893, Smith commissioned America's first reinforced concrete building, the Pacific Coast Borax Company refinery in Alameda, California.[18] The architect was Ernest L. Ransome.

In 1895, Smith formed a partnership with Frank C. Havens called the Realty Syndicate, which developed projects including the Key System, a major urban and suburban commuter train, ferry and streetcar system serving the East Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), Idora Park, the Key Route Inn and the Claremont Hotel.

In 1896, Smith acquired an estate and constructed a mansion, across the street from the MacArthur and Park Blvd. location of Oakland High School's current campus, where he lived until 3 years prior to his death in 1931.[19]

Railroad

editSmith developed a special interest in expanding his business into rail transportation and real estate. His first railroad, the narrow-gauge Borate and Daggett Railroad was built only to ship borax. Later, however, Smith created the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad, not only to ship borax, but also with an eye on the ore and passengers from the boomtown of Rhyolite, Nevada in the Bullfrog Mining District. This line was built in direct competition with the "Copper King" William A. Clark's Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad.[20]

Charitable work

editSmith was involved in significant charitable and community events during his lifetime. He frequently made his Oakland and Shelter Island estates available for fundraising activities, involving his children in running games and booths.

Supporting his first wife's desire to provide homelike accommodations for orphaned girls, Smith financed the construction and operation of 13 residential homes. Each home had a house mother selected by Mrs. Smith, who was directed to provide a normal home life for the girls under her care. Smith also provided a social hall called The Home Club, which was located on the site of the current Oakland High School. Only the stairway from Park Blvd. remains today. The homes operated for many decades, and several remain standing. As the State assumed care for orphans, the Mary R. Smith Trust was redirected to providing nursing education for qualified young women.[19]

Political work

editFrank Smith served as an Electoral College presidential elector in the 1912 election. He made his carriage available to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft during their visits to Oakland. The carriage is now displayed at the Oakland Museum of California.

Last years

editAfter suffering a major stroke at age 82 in 1928, Smith moved with his wife from their Oakland mansion and estate into a smaller residence across Lake Merritt in the Adams Point neighborhood. Prior to moving, several large pieces of the estate's gardens had been sold on which more modest homes were built. With the stock market crash of 1929, no buyer could be found for the remaining estate and shortly after his death the mansion was demolished after many remarkable and marketable fixtures were removed and sold.

Francis Marion Smith died in Oakland in 1931 at the age of 85. He is buried in the Mountain View Cemetery of Oakland, along "Millionaires Row".[21]

Legacy

editThe Western Railway Museum's archives wing is named for Francis Marion "Borax" Smith. The museum, in Solano County, California, includes several operating street cars and transbay trains that operated on the Key System lines.

Francis Marion Smith Park, on land donated by Smith and his wife, is on Park Boulevard in Oakland.

In Death Valley, Smith Mountain, a 5,915 feet (1,803 m) peak in the Amargosa Range, is named in his honor.[22]

On Shelter Island, NY, Smith Street and Smith Cove are named for him. The Smith-Ransome Japanese Bridge at Presdeleau is listed on the National Register of Historic places.

"Borax" Smith is a character in the historical fiction novel Carter Beats the Devil by Glen David Gold (ISBN 0-7868-8632-3), and the main character in Jack London's novel Burning Daylight was partially based on his life.[23]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ George Earlie Shankle "American nicknames; their origin and significance" 2nd Ed. 1955 pg. 417 ISBN 0-8242-0004-7, ISBN 978-0-8242-0004-6

- ^ Hildebrand (1982), p. xiii.

- ^ Donaldson Brothers (printer) (1872). "Smith brothers pure borax for sale everywhere". calisphere.org. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Legends of America-Francis "Borax" Marion Smith

- ^ a b c Orr, Patti (November 30, 2021). "History of Pacific Coast Borax and the Rio-Tinto Mine". Mojave Desert News. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Francis Marion Smith". Goldfield Historical Society. Goldfield, Nevada. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "American Borax Production". Scientific American. Vol. 37, no. 12. September 22, 1877. pp. 184–185. JSTOR 26062263.. The article states that the distance between Columbus, Nevada and Wadsworth, Nevada is "about 360 miles" whereas today the distance on modern roads is about 160 miles.

- ^ a b Hildebrand (1982), p. 56.

- ^ Hildebrand (1982), p. 48-59.

- ^ Rio Tinto Company Website Archived 2012-09-18 at archive.today

- ^ "Industrial minerals and extractive industry geology" Edited by P. W. Scott, Colin Malcolm Bristow, Geological Society of London. p. 90.

- ^ Fairchild, James L. (2015). Around Trona and Searles Valley. Russell L. Kaldenberg, Searles Valley Historical Society. Charlestown, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4396-5279-4. OCLC 967392495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Mary R. Smith". Oakland Wiki. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Francis Marion 'Borax' Smith". Oakland Wiki. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Arbor Villa". Oakland Wiki. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "OHS Database".

- ^

- Shillingburg, Edward; Shillingburg, Patricia. "Frank Smith, the Borax King, on Shelter Island". Shelter-Island.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Shillingburg, Edward; Shillingburg, Patricia. "Frank Smith, the Borax King, on Shelter Island". Shelter-Island.org. Shillingburg & Associates. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Greater Oakland, 1911" Ed. by Evarts I. Blake, p.278

- ^ a b Allen, Annalee (30 August 2008). "Tracking the steps of 'Borax'". East Bay Times. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "The Great Desert Railroad Race" Documentary written and produced by Ted Faye on YouTube

- ^ "The Story of Francis Marion Smith; Borax King". Mojave Desert News. 2022-11-10. Retrieved 2024-01-02.

- ^ Hanna, Phil Townsend. "The dictionary of California land names". 1951. Page 309

- ^ Hildebrand (1982), p. 1.

Sources

edit- Hildebrand, G.H. (1982). Borax Pioneer: Francis Marion Smith. San Diego: Howell-North Books. ISBN 0-8310-7148-6.

- Smythe, Dallas Walker (1937). An Economic History of Local and Interurban Transportation in the East Bay Cities with Particular Reference to the Properties Developed by F. M. Smith. Berkeley: University of California.

- Smith, Francis Marion. (Unpublished) circa 1925. Autobiographical Notes on His Early Life.

- Townsend, Charles E. (July 1903). "The Borax Industry And Its Chief Promoter". Overland Monthly. XLII: 24.

Further reading

edit- "Francis Marion Smith papers, 1888-1944, bulk 1902-1923". Oakland Public Library.

- "Mae Burdge Miller eulogy : and related papers, 1974". oac.cdlib.org.

- "J. Henry Strachan letterpress copybook". oac.cdlib.org.

- "Joseph Wakeman Mather papers, 1885-1889". oac.cdlib.org.

- "J. Henry Strachan letterpress copybook". oac.cdlib.org.

- "Views of Oakland, California, ca. 1930-1939". oac.cdlib.org.

- "Arbor Villa: the Home of Mr. & Mrs. F. M. Smith, Photographed by E. T. Dooley, 1902". oac.cdlib.org.