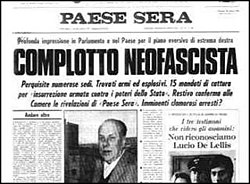

The Golpe Borghese (English: Borghese Coup) was a failed Italian coup d'état allegedly planned for the night of 7 or 8 December 1970. It was named after Junio Valerio Borghese, wartime commander of the Decima Flottiglia MAS and a hero in the eyes of many post-War Italian fascists. The coup attempt became publicly known when the left-wing journal Paese Sera ran the headline on the evening of 18 March 1971: Subversive plan against the Republic: far-right plot discovered.

| Golpe Borghese | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Years of lead and Neo-fascist activity in Italy | |

Front page of the newspaper Paese Sera on the failed neo-fascist coup | |

| Date | 7–8 December 1970 |

| Location | Rome |

| Goals | Overthrow of centre-left national government |

| Methods | Coup d'etat |

| Resulted in | Coup suspended |

The secret operation was code-named Operation Tora Tora after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[1] The plan of the coup in its final phase envisaged the involvement of US and NATO warships which were on alert in the Mediterranean Sea. Italian journalists have claimed the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reportedly followed the coup, with President Richard Nixon allegedly being personally informed of it. Yet in leaked documents, the US ambassador to Rome is quoted saying "The last thing we need right now is a half-cooked coup d’état … We wouldn’t support it."[2]

The alleged coup

editThe botched right-wing coup took place after the Hot Autumn of left-wing protests in Italy and the Piazza Fontana bombing in December 1969, while in Reggio Calabria the Reggio revolt was supported by neofascists and ongoing. The failed coup involved hundreds of neo-fascist militants from Stefano Delle Chiaie's National Vanguard, and army dissidents under Lt. Colonel Amos Spiazzi, helped by 187 members of the Corpo Forestale dello Stato, who were to seize the headquarters of the Italian public television broadcaster RAI.[3][4] The plan included the kidnapping of the Italian President Giuseppe Saragat; the murder of the head of the police Angelo Vicari; and the occupation of RAI, the Quirinale, the Ministry of the Interior (from which Vanguard militants would seize weapons), and the Ministry of Defense. Spiazzi's Milan-based battalion also planned to occupy Sesto San Giovanni, at that time a workers' town and a stronghold of the Italian Communist Party. Apparently some militants briefly entered the Ministry of the Interior, but Borghese suspended the coup a few hours before its final phase. A submachine gun (a Beretta Model 38) not returned by one of the militants was later viewed as a key piece of evidence in the sedition trial.[3]

According to Borghese, the neo-fascists were actually gathering for a protest demonstration against the upcoming visit of President Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, which was later postponed. This protest was supposedly called off because of heavy rain.[5] According to the later testimony of Spiazzi, the coup was in fact fictitious: it would have been immediately suppressed by government forces through an emergency plan called Esigenza Triangolo (Triangle Exigency) similar to the 1964 Piano Solo, which would have provided the Christian Democratic (DC) government an excuse to declare martial law and enact special laws allowing the deployment of thousands of government troops, as well as military and civil police to seize control of political parties and publishers and undertake mass arrests and deportations, to quell the ongoing social unrest and left-wing protests.[6] However, Borghese, for unknown reasons or acting on a tip off, aborted the coup at the last minute as the plotters moved into position.[6]

Participants at the semi-clandestine rallies seem to have believed that they would take part in the arrest of politicians and the occupation of key installations by sympathetic army units. When Borghese called off the coup late that night, the presumed plotters, reportedly unarmed, improvised a late spaghetti dinner before returning home.[7] Several members of the National Front were arrested and a warrant was served for Borghese. Borghese himself fled to Spain and died there in August 1974.[8]

Inquiry

editOn 18 March 1971, the leftist journal Paese Sera was published with the headline: Subversive plan against the Republic: far-right plot discovered. The first arrests concerning the coup attempt were made on the same day. The first people arrested on 18 and 19 March were Mario Rose, a retired army major and National Front secretary; Remo Orlandini, also a former army major, a real-estate proprietor and close associate of Borghese; and Sandro Saccucci, a young paratrooper. An arrest warrant for Borghese was also served, but he could not be found.[9] Later arrestees included businessman Giovanni De Rosa and a retired Air Force colonel, Giuseppe Lo Vecchio.[10]

The investigation into the coup attempt was resurrected after Giulio Andreotti became defense minister again. Andreotti handed over a report by the secret service to the Rome public prosecutor in July 1974,[11] revealing a detailed knowledge of the inner workings of the conspiracy and links to members of the secret service.[1] Shortly thereafter, General Vito Miceli, a former head of SID, was brought for questioning before the investigating judge.[12] Miceli's interrogation led to his arrest two days later.[13] Miceli was then sacked, and the Italian intelligence agencies were reorganized by a 1977 law.

Trials

editThree trials were started for conspiracy against the Italian state. In 1978, Miceli was acquitted of trying to cover up a coup attempt. Saccucci, Orlandini, Rosa, and others were convicted of political conspiracy,[14] which also included Delle Chiaie, whose specific role is unclear. According to a 1987 UPI news cable, he had already fled Italy to Spain on 25 July 1970.[15] However, according to other sources, Delle Chiaie led the commando team which occupied the premises of the Interior Ministry.[16] At the appeal trial in November 1984, all 46 defendants were acquitted because the "fact did not happen" (il fatto non sussiste) and only existed in "a private meeting between four or five sixty-years-olds".[17][18] The Supreme Court of Cassation confirmed the appeal judgment in March 1986.[19]

The final trial connected with the Golpe Borghese began in 1991, after it was discovered that evidence involving prominent persons (Licio Gelli and admiral Giovanni Torrisi) had been destroyed by the secret service before the first trial. Andreotti, minister of defence at the time the evidence was destroyed, declared in 1997 that names had been deleted so that the charges would be easier to understand. This last trial ended without convictions because the period of prescription for destruction of evidence had passed.[17]

According to the journalist René Monzat, investigations lasted seven years, during which it was alleged that the Golpe Borghese had benefited from military accomplices, as well as from political support not only from the National Front and from MSI deputy Sandro Saccucci, but also from other political personalities belonging to the DC and to the Italian Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI).[16] According to Monzat, investigations also discovered that the military attaché at the US embassy was closely connected to the coup organizers and that one of the main accused declared to the magistrate that US President Richard Nixon had followed the preparations for the coup, of which he was personally informed by two CIA officers.[16] These facts were confirmed through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by the Italian newspaper La Repubblica in December 2004. However, only a few marginalized sectors of the CIA were in favour of the coup, while the main response was not to allow major changes in the geopolitical balance in the Mediterranean.[17]

Involvement of the Mafia

editAccording to several state witnesses (pentiti) such as Tommaso Buscetta, Borghese asked the Sicilian Mafia to support the coup. In 1970, when the Sicilian Mafia Commission was reconstituted, one of the first issues that had to be discussed was an offer by Borghese, who asked for support in return for pardons of convicted mafiosi like Vincenzo Rimi and Luciano Leggio. The mafiosi Giuseppe Calderone and Giuseppe Di Cristina visited Borghese in Rome. However, other mafiosi such as Gaetano Badalamenti opposed the plan, and the Mafia decided not to participate.[20]

According to Leggio, testifying at the Maxi Trial against the Mafia in the mid-1980s, Buscetta and Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco were in favour of helping Borghese. The plan was for the Mafia to carry out a series of terrorist bombings and assassinations to provide the justification for a right-wing coup. Although Leggio's version differed from Buscetta's, the testimony confirmed that Borghese had requested assistance by the Mafia.[21] According to the pentito Francesco Di Carlo, the journalist Mauro De Mauro was killed in September 1970 because he had learned that Borghese – one of De Mauro's childhood friends – was planning the coup.[22][23][24]

Significance

editThe failed coup has gone down in history as "a comic-opera coup staged by naive incompetents, which posed no real threat to the state" and newspapers wrote about it as "the coup that never was".[11] Nonetheless, the secret service reported connections with the Nixon administration and NATO units in Malta based on claims made by Orlandini. Orlandini asserted that the plotters would receive assistance from a NATO fleet, though this never materialized.[25]

In popular culture

editA comic film directed by Mario Monicelli and starring popular Italian actor Ugo Tognazzi was released in 1973 and was in the selection of Italian films for the 1973 Cannes Film Festival. It is called Vogliamo i colonelli (We Want the Colonels, in reference to the contemporary US-backed Greek military dictatorship). In this film, Tognazzi portrays a boisterous and clumsy far right MP called Tritoni trying to stage a coup against the government. Though the botched attempt sinks in ridicule and chaos, and Tritoni has to go in exile, right wing political measures are nevertheless enforced, such as forbidding labor strikes and political gatherings. The character's name Tritoni (Triton) is a direct reference to Borghese and his military past as the leader of an assault frogmen unit. The film is peppered with joke references to the fascist period, the post-war neo-fascist Italian Social Movement and the Decima MAS frogmen unit.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Willan, Puppetmasters p. 91

- ^ "Golpe Borghese, all the CIA papers". 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Willan, Puppetmasters p. 91-92

- ^ "Quarantasei anni fa il colpo di stato "negato"". Fondazione Pietro Nenni. 8 December 2016.

- ^ Prince's Lawyers Deny Charge, The New York Times, 22 March 1971

- ^ a b (in Italian) Dianese & Bettin, La strage, pp. 165–69

- ^ Italian Police Track Leftist Terrorists, The New York Times, 29 March 1971

- ^ Prince Junio Borghese, 68, Dies; Italian War Hero and Neofascist, The New York Times, 28 August 1974

- ^ "Rome Police Arrest Another in Alleged Neo-Fascist Plot". The New York Times. 21 March 1971. p. 29.

- ^ "Colonel Arrested on Rome Plotting Charge". The Times. 24 March 1971. p. 6.

- ^ a b Willan, Puppetmasters, p. 90

- ^ "General to Tell of Coup Attempt". The Times. 29 October 1974. p. 8.

- ^ "General Who Led Intelligence Agency Arrested in Italy". The New York Times. 1 November 1974. p. 5.

- ^ "Jail Terms for 1970 Italian Coup Plotters". The Times. 15 July 1978. p. 3.

- ^ "Neo-fascist held in isolation to await questioning". United Press International. 1 April 1987.

- ^ a b c René Monzat, Enquêtes sur la droite extrême, Le Monde-éditions, 1992, p.84

- ^ a b c (in Italian) Il golpe Borghese. Storia di un'inchiesta Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, La storia siamo noi, Rai Educational (accessed 24 February 2011)

- ^ (in Italian) E la Cia disse: sì al golpe Borghese ma soltanto con Andreotti premier, La Repubblica, 5 December 2005

- ^ (in Italian) Il golpe Borghese: La vicenda giudiziaria Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Misteri d'Italia website

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 151-53

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 186

- ^ (in Italian) "De Mauro venne ucciso perché sapeva del golpe", La Repubblica, 26 January 2001

- ^ (in Italian) De Mauro ucciso per uno scoop: scoprì il patto tra boss e golpisti, La Repubblica, 18 June 2005

- ^ Revealed: how story of Mafia plot to launch coup cost reporter his life, The Independent on Sunday, 19 June 2005

- ^ Willan, Puppetmasters, p. 93

Sources

edit- (in Italian) Dianese, Maurizio & Bettin, Gianfranco (1999). La strage. Piazza Fontana. Verità e memoria, Milan: Feltrinelli, ISBN 88-07-81515-X

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers. The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic, New York: Vintage ISBN 0-09-959491-9

- (in Italian) Relazione della Commissione Stragi su "Il terrorismo, le stragi ed il contesto storico-politico": cap. VI, "Il c.d. golpe Borghese"

- Willan, Philip P. (1991/2002). Puppetmasters: The Political Use of Terrorism in Italy, New York: Authors Choice Press, ISBN 0-595-24697-4

External links

edit- (in Italian) Il golpe Borghese: La vicenda giudiziaria Misteri d'Italia website