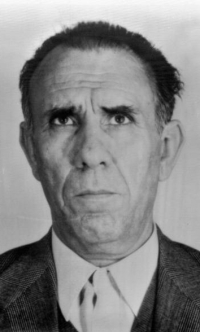

Gaetano Badalamenti (Italian pronunciation: [ɡaeˈtaːno badalaˈmenti]; 14 September 1923 – 29 April 2004) was a powerful member of the Sicilian Mafia. Don Tano Badalamenti was the capofamiglia of his hometown Cinisi, Sicily, and headed the Sicilian Mafia Commission in the 1970s. In 1987, he was sentenced in the United States to 45 years in federal prison for being one of the leaders in the "Pizza Connection", a $1.65 billion drug-trafficking ring that used pizzerias as fronts to distribute heroin from 1975 to 1984.[1][2] He was also sentenced in Italy to life imprisonment in 2002 for the 1978 murder of Peppino Impastato.

Gaetano Badalamenti | |

|---|---|

Gaetano Badalamenti | |

| Born | 14 September 1923 |

| Died | 29 April 2004 (aged 80) Ayer, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Other names | Don Tano |

| Children | Vito Badalamenti |

| Allegiance | Cosa Nostra |

| Conviction(s) | Drug trafficking (1987) Murder (2002) |

| Criminal penalty | 45 years' imprisonment and fined $125,000 Life imprisonment |

Early years

editTano Badalamenti was the youngest of a family with five boys and four girls. His family owned a dairy farm in Cinisi. He had minimal schooling, attending school for only four years, before he was put to work as a field hand at age ten. In 1941, he was conscripted into the Royal Italian Army and deserted during the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943.[3] His elder brother Emanuele Badalamenti had moved to the United States and operated a supermarket and gas station in Monroe, Michigan. In 1946 Gaetano was named in an arrest warrant on charges of conspiracy and kidnapping. In 1947 he was charged with murder as well, and he fled to his brother Emanuele in the US. Badalamenti was arrested in 1950 and deported back to Italy. He married Theresa Vitale (her sister was married to Filippo Rimi, the capomafia of Alcamo) and set up a business on the family land as a lemon grower. His judicial difficulties were all resolved because of insufficient evidence.

Badalamenti founded a successful construction business that supplied the crushed rock for Palermo's Punta Raisi Airport which fell within the Cinisi family's sphere of influence. In the early 1960s, he successfully bribed officials to have the airport built near his hometown, despite its inconvenient geographical position. The construction needed supplies of rock and gravel, which were available in large quantities on the family property. His two construction firms, a concrete plant and a fleet of trucks provided much needed employment for the townsfolk and enriched Badalamenti.

Capomafia of Cinisi

editBadalamenti assumed leadership of the Mafia in Cinisi in 1963 after a car bomb killed Cesare Manzella during the First Mafia War. The Ciaculli Massacre on 30 June 1963 – when seven police and military officers sent to defuse a car bomb intended for mafioso Salvatore Greco were killed – changed the Mafia War into a war against the Mafia. It prompted the first concerted anti-mafia efforts by the state in post-war Italy. Within a period of ten weeks 1,200 mafiosi were arrested, many of whom would be kept out of circulation for five or six years. The Sicilian Mafia Commission was dissolved.[4][5]

Badalamenti had complete control in Cinisi. "It seemed that Badalamenti was well liked by the Carabinieri as he was calm, reliable, and always liked a chat. It almost felt like he was doing them a favour in that nothing ever happened in Cinisi, it was a quiet little town." and "I often used to see them walking arm in arm with Tano Badalamenti and his henchmen. You can't have faith in the institutions when you see the police arm in arm with mafiosi", according to Giovanni Impastato – the brother of murdered anti-mafia activist Giuseppe Impastato – in his declaration before the Italian Antimafia Commission.[6]

Pizza connection

editGaetano Badalamenti would become one of the major heroin traffickers of the Sicilian Mafia. From 1975 to 1984, he was one of the main ringleaders of a US$1.65 billion heroin trafficking operation, known as the Pizza Connection, that imported heroin from the Middle East and distributed the drugs through U.S. mid-western pizzeria store fronts.[2][7] In 1951, the American police identified a 50 kilogram shipment of heroin to Badalamenti who was then living in Detroit as an illegal immigrant. However, in the 1950s most money was made by smuggling foreign cigarettes into Italy. In 1953 Badalamenti was arrested for cigarette smuggling in Italy for the first time. In 1957 he was caught again with 3,000 kilograms of foreign-made cigarettes. The repression caused by the Ciaculli Massacre disrupted the Sicilian heroin trade to the United States. Mafiosi were banned, arrested and incarcerated. Control of the trade fell into the hands of a few fugitives: the cousins Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco and Salvatore Greco, also known as "l'ingegnere", Pietro Davì, Tommaso Buscetta and Gaetano Badalamenti.[8]

In 1970, the Sicilian Mafia Commission was revived. It consisted of ten members but was initially ruled by a triumvirate consisting of Gaetano Badalamenti, Stefano Bontade and the Corleonesi boss Luciano Leggio, although it was Salvatore Riina who would actually represent the Corleonesi.[9][10] One of the first issue that had to be confronted was an offer of Prince Junio Valerio Borghese who asked for support for his plans for a neofascist coup in return for a pardon of convicted mobsters like Vincenzo Rimi and Luciano Leggio. Giuseppe Calderone and Di Cristina went to visit Borghese in Rome. Badalamenti opposed the plan. However, the Golpe Borghese fizzled out in the night of 8 December 1970.[11][12]

In 1974 the full Commission was reconstituted under the leadership of Badalamenti. The Commission was meant to settle disputes and keep the peace, but Salvatore Riina, was plotting to decimate the Palermo clans. After 1975, Badalamenti joined forces with Salvatore Catalano of the Sicilian faction in the Bonanno family in New York and was involved with the "Pizza Connection" case, where the mafia smuggled millions worth of heroin and cocaine to the United States using mafia-owned pizzerias as distribution points. In January 1978, the old and ailing former head of the Commission Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco came all the way from Venezuela to try to restrain Badalamenti, Giuseppe Di Cristina and Giuseppe Calderone from retaliating against the growing power of the Corleonesi. Di Cristina and Badalamenti wanted to kill Francesco Madonia, the boss of Vallelunga Mafia family and an ally of the Corleonesi in the province of Caltanissetta. Greco tried to convince them not to go ahead and offered Di Cristina to emigrate to Venezuela. Nevertheless, Badalamenti and Di Cristina decided to go on and on 8 April 1978, Francesco Madonia was murdered. In retaliation, Di Cristina was killed in May 1978 by the Corleonesi. Next was Giuseppe Calderone, who was killed on 8 September 1978. Later in 1978, Gaetano Badalamenti was expelled from the Commission, and Michele Greco replaced him.[13]

Badalamenti was replaced as head of the Cinisi Mafia family by his cousin Antonio Badalamenti. He fled to Brazil through Spain and settled in São Paulo. In 1984, again through telephone interceptions, the FBI discovered that Badalamenti had planned a meeting in Madrid with his nephew Pietro "Pete" Alfano, owner of a pizzeria in Oregon, Illinois, and considered him the "main point of contact in the United States" for heroin trafficking.[2][14] On 8 April 1984, in Madrid, Spain, the agents of the FBI and those of the Italian and Spanish police arrested Badalamenti and his son Vito Badalamenti together with Pietro Alfano;[15] on 15 November, they were extradited to the United States.[16] In 1985, Badalamenti, and over a dozen other defendants were on trial in New York,[17] in what became known as the "Pizza Connection" case. The trial lasted about 17 months, the longest in the judicial history of the United States,[17] ending on 2 March 1987 with a conviction for Badalamenti and Salvatore Catalano, who were each sentenced to 45 years in prison on 22 June 1987.[18] Only his son Vito was released after being acquitted.[19] Gaetano Badalamenti was also fined $125,000, and since he was extradited from Spain with the provision that he serve no more than 30 years, he was ordered to be released after 30 years should he live that long.[20]

Political contacts and murder charge

editItaly's highest court, the Court of Cassation, ruled in October 2004 that former Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti had "friendly and even direct ties" with top men in the moderate wing of Cosa Nostra, Gaetano Badalamenti and Stefano Bontade, favored by the connection between them and Salvo Lima through the Salvo cousins. According to investigating magistrates Andreotti also commissioned the Mafia to kill the journalist Mino Pecorelli, managing editor of a magazine Osservatorio Politico (OP). The murder took place on 20 March 1979. On 6 April 1993, Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta told Palermo prosecutors that he had learnt from his boss Badalamenti that Pecorelli's murder had been carried out in the interest of Andreotti. The Salvo cousins, two powerful Sicilian politicians with deep ties to local Mafia families, were also involved in the murder. Buscetta testified that Gaetano Badalamenti told him that the murder had been commissioned by the Salvo cousins as a favor to Andreotti. Andreotti was allegedly afraid that Pecorelli was about to publish information that could have destroyed his political career. Among the information was the complete memorial of Aldo Moro, which would be published only in 1990 and which Pecorelli had shown to General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa before his death.[21]

Dalla Chiesa was assassinated by Mafia in September 1982. Andreotti was acquitted along with his co-defendants in 1999.[22] Local prosecutors successfully appealed the acquittal and there was a retrial, which in 2002 convicted Andreotti and sentenced him to 24 years imprisonment. Italians of all political allegiances denounced the conviction.[23][24] Many failed to understand how the court could convict Andreotti of orchestrating the killing, yet acquit his co-accused, who supposedly had carried out his orders by setting up and committing the murder.[25] The Italian supreme court definitively acquitted Andreotti of the murder in 2003.[26][27] In April 2002, an Italian court convicted Badalamenti of the 1978 murder of activist radio broadcaster Peppino Impastato and sentenced him to life imprisonment.[6][28] Impastato used humor and satire as his weapon against the Mafia. In his popular daily radio program Onda pazza (Crazy Wave) he mocked politicians and mafiosi alike. On a daily basis he exposed the crimes and dealings of mafiosi in Mafiopoli (Cinisi) and the activities of Tano Seduto (Sitting Tano), a thinly disguised pseudonym of Don Tano Badalamenti, the capomafia of Cinisi.[6][29]

Death

editOn 29 April 2004, Badalamenti died from heart failure, at the age of 80, at the Devens Federal Medical Center in Ayer, Massachusetts.[30] Ralph Blumenthal, a New York Times reporter, depicted Badalamenti as "a manipulator who would do anything to regain leadership of the Sicilian mob" in his 1988 book, Last Days of the Sicilians. Shana Alexander, portrayed him as "a man of unusual dignity" in her book The Pizza Connection, published the same year.[3]

References

edit- ^ "Family Affairs: Two Mafia cases go to court", Time, 14 October 1985.

- ^ a b c "Extra Cheese: Busting a pizza connection", Time, 23 April 1984.

- ^ a b "Gaetano Badalamenti, 80; Led Pizza Connection Ring", The New York Times (Obituary), 3 May 2004.

- ^ Schneider & Schneider, Reversible Destiny, p. 65-66

- ^ Servadio, Mafioso, p. 181

- ^ a b c Giuseppe Impastato: his actions, his murder, the investigation and the cover up Archived 9 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine by Tom Behan, Centro Siciliano di Documentazione "Giuseppe Impastato".

- ^ "The Sicilian Connection", Time, 15 October 1984.

- ^ The Rothschilds of the Mafia on Aruba, by Tom Blickman, Transnational Organized Crime, Vol. 3, No. 2, Summer 1997

- ^ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 337-38

- ^ Sterling, Octopus, p. 112

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 151-53

- ^ (in Italian) "De Mauro venne ucciso perché sapeva del golpe", La Repubblica, 26 January 2001

- ^ "Il contesto mafioso e don Tano Badalamenti - Documenti del Senato della Repubblica XIII Legislatura (III parte)" (PDF) (in Italian).

- ^ "The Pizza Connection". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Gaetano Badalamenti Si Rifiuta Di Rispondere Al Magistrato - La Repubblica.It

- ^ impastato-cronologia le vicende del processo

- ^ a b La Fine Di ' Pizza Connection' - la Repubblica.it

- ^ 'Pizza Connection' Badalamenti Condannato a 45 Anni - Repubblica.it » Ricerca

- ^ "Acquitted in 'Pizza Connection' Trial, Man Remains in Prison", The New York Times, 28 July 1988.

- ^ "Five of the top defendants in the 'pizza connection'..." UPI. 22 June 1987.

- ^ Calabrò, Maria Antonietta (15 April 1993). "Intreccio Pecorelli-Moro: già da un anno s'indaga". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (25 September 1999). "Ex-Premier Andreotti Acquitted of Mafia Murder Conspiracy". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Court Clears Andreotti of Murder Charge". The New York Times. 31 October 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Bruni, Frank (19 November 2002). "Andreotti's Sentence Draws Protests About 'Justice Gone Mad'". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Andreotti fights back on Mafia allegations". The Age. 30 November 2002. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Giulio Andreotti". The Daily Telegraph. 6 May 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Giulio Andreotti". The Daily Telegraph. 6 May 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ (in Italian) Sentenza nel procedimento penale contro Badalamenti Gaetano, Corte di Assise di Palermo, 11 April 2002

- ^ (in Italian) Caso Impastato final report of the Italian parliamentary Antimafia Commission, 6 December 2000

- ^ 'Pizza Mafioso' dies in US prison, BBC News obituary, Saturday, 1 May 2004

Bibliography

edit- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Gambetta, Diego (1993). The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection, London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-80742-1

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style, New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515724-9

- Schneider, Jane T. & Peter T. Schneider (2003). Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo, Berkeley: University of California Press ISBN 0-520-23609-2

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso: a History of the Mafia from Its Origins to the Present Day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-440-55104-8

- Shawcross, Tim & Martin Young (1987). Men of Honour: The Confessions of Tommaso Buscetta, Glasgow: Collins ISBN 0-00-217589-4

- Sterling, Claire (1990). Octopus: How the Long Reach of the Sicilian Mafia Controls the Global Narcotics Trade, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-73402-4

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers: The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic, New York: Vintage ISBN 0-09-959491-9