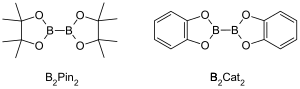

Metal-catalyzed C–H borylation reactions are transition metal catalyzed organic reactions that produce an organoboron compound through functionalization of aliphatic and aromatic C–H bonds and are therefore useful reactions for carbon–hydrogen bond activation.[1] Metal-catalyzed C–H borylation reactions utilize transition metals to directly convert a C–H bond into a C–B bond. This route can be advantageous compared to traditional borylation reactions by making use of cheap and abundant hydrocarbon starting material, limiting prefunctionalized organic compounds, reducing toxic byproducts, and streamlining the synthesis of biologically important molecules.[2][3] Boronic acids, and boronic esters are common boryl groups incorporated into organic molecules through borylation reactions.[4] Boronic acids are trivalent boron-containing organic compounds that possess one alkyl substituent and two hydroxyl groups. Similarly, boronic esters possess one alkyl substituent and two ester groups. Boronic acids and esters are classified depending on the type of carbon group (R) directly bonded to boron, for example alkyl-, alkenyl-, alkynyl-, and aryl-boronic esters. The most common type of starting materials that incorporate boronic esters into organic compounds for transition metal catalyzed borylation reactions have the general formula (RO)2B-B(OR)2. For example, bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2Pin2), and bis(catecholato)diborane (B2Cat2) are common boron sources of this general formula.[5]

The boron atom of a boronic ester or acid is sp2 hybridized possessing a vacant p orbital, enabling these groups to act as Lewis acids. The C–B bond of boronic acids and esters are slightly longer than typical C–C single bonds with a range of 1.55-1.59 Å. The lengthened C–B bond relative to the C–C bond results in a bond energy that is also slightly less than that of C–C bonds (323 kJ/mol for C–B vs 358 kJ/mol for C–C).[6] The carbon–hydrogen bond has a bond length of about 1.09 Å, and a bond energy of about 413 kJ/mol. The C–B bond is therefore a useful intermediate as a bond that replaces a typically unreactive C–H bond.

Organoboron compounds are organic compounds containing a carbon-boron bond. Organoboron compounds have broad applications for chemical synthesis because the C–B bond can easily be converted into a C–X (X = Br, Cl), C–O, C–N, or C–C bond. Because of the versatility of the C–B bond numerous processes have been developed to incorporate them into organic compounds.[7] Organoboron compounds are traditionally synthesized from Grignard reagents through hydroboration, or diboration reactions.[8] Borylation provides an alternative.

Metal-catalyzed C–H borylation reactions

editAs first described by Hartwig, alkanes can be selectively borylated with high selectivity for the primary C–H bond using Cp*Rh(η4-C6Me6) as the catalyst.[9] Notably, selectivity for the primary C–H bond is exclusive even in the presence of heteroatoms in the carbon-hydrogen chain. The rhodium-catalyzed borylation of methyl C–H bonds occurs selectively without a dependence on the position of the heteroatom. Borylation occurs selectively at the least sterically hindered and least electron rich primary C–H bond in a range of acetals, ethers, amines, and alkyl fluorides.[10] Additionally, no reaction is shown to occur in the absence of primary C–H bonds, for example when cyclohexane is the substrate.

Selective functionalization of a primary alkane bond is due to the formation of a kinetically and thermodynamically favorable primary alkyl-metal complex over formation of a secondary alkyl-metal complex.[11]

The greater stability of primary versus secondary alkyl complexes can be attributed to several factors. First, the primary alkyl complex is favored sterically over the secondary alkyl complex. Second, partial negative charges are often present on the α-carbon of a metal-alkyl complex and a primary alkyl ligand supports a partial negative charge better than a secondary alkyl ligand. The origin of selectivity for aliphatic C–H borylation using rhodium catalysts was probed using a type of mechanistic study called hydrogen–deuterium exchange. H/D exchanged showed that regioselectivity of the overall process shown below results from selective cleavage of primary over secondary C–H bonds and selective functionalization of the primary metal-alkyl intermediate over the secondary metal-alkyl intermediate.[12]

The synthetic utility of aliphatic C–H borylation has been applied to the modification of polymers through borylation followed by oxidation to form hydroxyl-functionalized polymers.[13]

Aromatic C–H borylation

editSteric directed C–H borylation of arenes

editThe first example of a catalytic C–H borylation of an unactivated hydrocarbon (benzene) was reported by Smith and Iverson using Ir(Cp*)(H)(Bpin) as the catalyst. The efficiency of this system, however, was low, providing only 3 turnovers after 120 h at 150 °C.[14] Numerous subsequent developments by Hartwig and coworkers led to efficient, practical conditions for arene borylation. Aromatic C–H borylation was developed by John F. Hartwig and Ishiyama using the diboron reagent Bis(pinacolato)diboron catalyzed by 4,4’-di-tert-butylbipyridine (dtbpy) and [Ir(COD)(OMe)]2.[15] With this catalyst system the borylation of aromatic C–H bonds occurs with regioselectivity that is controlled by steric effects of the starting arene. The selectivity for functionalization of aromatic C–H bonds is governed by the general rule that the reaction does not occur ortho to a substituent when a C–H bond lacking an ortho substituent is available.[11] When only one functional group is present borylation occurs in the meta and para position in statistical ratios of 2:1 (meta:para). The ortho isomer is not detected due to the steric effects of the substituent.[16]

Addition of Bpin occurs in only one position for symmetrically substituted 1,2- and 1,4-substituted arenes. Symmetrical or unsymmetrical 1,3-substituted arenes are also selectively borylated because only one C–H bond is sterically accessible.

This is in contrast to Electrophilic aromatic substitution where regioselectivity is governed by electronic effects.[17]

The synthetic importance of aromatic C–H borylation is shown below, where a 1,3-disubstituted aromatic compound can be directly converted to a 1,3,5-organoborane compound and subsequently functionalized.[15]

Aromatic C–H functionalization was successfully incorporated in the total synthesis of Complanadine A, a Lycopodium alkaloid that enhances mRNA expression for nerve growth factor (NGF) and the production of NGF in human glial cells. Natural products that promote the growth of new neural networks are of interest in the treatment of diseases such as Alzheimer's disease.[18] Complanadine A was successfully synthesized using a combination of direct aromatic C–H borylation developed by Hartwig and Ishyiama, followed by Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling, then cleavage of the Boc protecting group.

C–H borylation of heteroarenes

editHeteroarenes can also undergo borylation under iridium-catalyzed conditions, however, site-selectivity in this case is controlled by electronic effects, where furans, pyrroles, and thiophenes undergo reaction at the C–H bond alpha to the heteroatom. In this case selectivity is suggested to occur through the C–H bond alpha to the heteroatom because it is the most acidic C–H bond and therefore the most reactive.[11]

Directed ortho C–H borylation

editUsing the same catalyst system directing groups can be employed to achieve regioselectivity without substituents as steric mediators. For example, Boebel and Hartwig reported a method to conduct ortho-borylation where a dimethyl-hydrosilyl directing group on the arene undergoes iridium catalyzed borylation at the C–H bond ortho to the silane directing group.[19] Selectivity for the ortho position in the case of using hydrosilyl directing groups has been attributed to reversible addition of the Si-H bond to the metal center, leading to preferential cleavage of the C–H bond ortho to the hydrosilyl substituent. Several other strategies to achieve ortho-borylation of arenes have been developed using various directing groups.[20][21][22]

Mechanistic detail for the C–H borlyation of arenes

editA trisboryl iridium complex has been proposed to facilitate the mechanism for each of these reactions that result in C–H borylation of arenes and heteroarenes. Kinetic studies and isotopic labelling studies have revealed that an Ir(III) triboryl complex reacts with the arene in the catalytic process.[23] A version of the catalytic cycle is shown below for the ortho borylation of hydrosilane compounds. Kinetic data show that an observed trisboryl complex coordinated to cyclooctene rapidly and reversibly dissociates cyclooctene to form a 16 electron trisboryl complex. In the case of using benzyldimethylsilane as a directing group it is proposed that benzyldimethylsilane reacts with the trisboryl iridium catalyst through reversible addition of the Si-H bond to the metal center, followed by selective ortho-C–H bond activation via oxidative addition and reductive elimination.[24]

Meta-selective borylation: Meta-selective C–H borylation is an important synthetic transformation, which was discovered in 2002 by Smith III from Michigan State University, USA. However, this meta borylation was completely sterically directed and was limited to only 1,3-disubstituted benzenes. Around 12 years later, Dr. Chattopadhyay and his team from Centre of Biomedical Research, U.P, India discovered an elegant technology for the meta-selective C–H bond activation and borylation. The team had shown that using the same substrate, one can switch the other positional selectivity just changing the ligand. The origin of the meta-selectivity was defined by the two parameter, such as: 1) electrostatic interaction, 2) a secondary B-N interaction.[25]

At the same time, a team from Japan, Dr. Kanai reported an amazing concept for the meta-selective borylation based on the secondary interaction. This method covers various carbonyl compounds borylation.[26]

Reduction reactions with organoboron compounds

editIn 1981, Hirao and co-workers have found that asymmetric reduction of prochiral aromatic ketones with chiral amino alcohols and borane afforded the corresponding secondary alcohols with 60% ee. They found out that the chiral amino alcohols would react with borane to form aloxyl-amine-borane complexes. The complexes are proposed to contain a relatively rigid five member-ring system which makes them thermal and hydrolytic stable and soluble in a wide variety of protic and aprotic solvents.[27]

In 1987, Elias James Corey and co-workers found out that the formation of oxazaborolidines from borane and chiral amino alcohols. And the oxazaborolidines were found to catalyze the rapid and highly enantioselective reduction of prochiral ketones in the presence of BH3THF. This enantioselective reduction of achiral ketones with catalytic oxazaborolidine is called Corey–Bakshi–Shibata reduction or CBS reduction.[28][29]

In 1977, M. M. Midland and co-workers reported a surprising observation that B-3-alpha-Pinanyl-9-borabicyclo [3,3,1] nonane, readily prepared by hydroboration of (+)-alpha-pinene with 9-borobicyclo[3,3,1] nonane, rapidly reduces benzaldehyde-alpha-d to (S)-(+)-benzyl-alpha-d alcohol with an essentially quantitative asymmetric induction.[30]

In the same year, M. M. Midland discovered B-3-alpha-pinanyl-9-BBN as the reducing agent, which could be easily available by reacting (+)-alpha-pinene with 9-BBN. The new reducing agent was later commercialized by Aldrich Co. under the name Alpine Borane and the asymmetric reduction of carbonyl groups with either enantiomer of Alpine-Borane is known as Midland Alpine-Borane reduction.[31]

In 2012, U. R. Y. Venkateswarlu and co-workers have reported a stereoselective method to synthesize pectinolide H. Midland reduction and Sharpless dihydroxylation reaction are involved in generating the three chiral centers at C–4’, C–5 and C–1’.[32]

Coupling reactions with organoboron compounds

editIn 1993, N. A. Petasis and I. Akrltopoulou reported an efficient synthesis of allylic amines with a modified Mannich reaction. In this modified Mannich reaction, they have found that vinyl boronic acids can participate as nucleophiles to give geometrically pure allylamines. This modified Mannich reaction was known as Petasis boronic acid-Mannich Reaction.[33][34]

Roush asymmetric allylation

editIn 1978, R. W. Hoffmann and T. Herold reported on the enantioselective synthesis of secondary homoallyl alcohols via chiral non-racemic allylboronic esters. The homoallylic alcohols were formed with excellent yield and moderate enantioselectivity.[35]

In 1985, W. R. Roush and co-workers found out that tartrate modified allylic boronates offer a simple, highly attractive approach to the control of facial selectivity in reactions with chiral and achiral aldehydes. In the following years, W.R. Roush and co-workers extended this strategy to the synthesis of but-2-ene-1,4-diols and anti-diols. This kind of reaction is known as Rouch asymmetric allylation.[36][37][38][39]

In 2011, R. A. Fernandes and P. Kattanguru have completed an improved total synthesis of (8S, 11R, 12R)- and (8R, 11R, 12R)-topsentolide B2 diastereomers in eight steps. In the paper, diastereoselective Roush allylation reaction was used as a key reaction in the total synthesis to introduce two chiral intermediate. And then the authors synthesized the two diastereomers through these two chiral intermediates.[40]

In 1979, N. Miyaura and A. Suzuki reported the synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes in high yield from aryl halides with alkyl-1-enylboranes and catalyzed by tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium and bases. Then A. Suzuki and co-workers extend this kind of reaction to other organoboron compounds and other alkenyl, aryl, alkyl halides and triflate. The palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction organoboron compounds and these organic halides to form carbon-carbon bonds are known as Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling.[41][42]

In 2013, Joachim Podlech and co-workers determined the structure of Alternaria mycotoxin altenuic acid III by NMR spectroscopic analysis and completed its total synthesis. In the synthetic strategy, Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling reaction was used with a highly functionalized boronate and butenolides to synthesize a precursor of the natural product in high yield.[43]

Modified Ullmann biaryl ether and biaryl amine synthesis

editIn 1904, Fritz Ullmann found out that copper powder could significantly improve the reaction of aryl halides with phenols to give biaryl ethers. This reaction is known as Ullmann condensation. In 1906, I. Goldberg extended this reaction to synthesize an arylamine by reacting aryl halides with an amide in the presence of Potassium Carbonate and CuI. This reaction is known as Goldberg modified Ullmann condensation.[44] In 2003, R. A. Batey and T. D. Quach have modified this kind of reactions by using potassium organotrifluoroborates salts to react with aliphatic alcohols, aliphatic amines or anilines to synthesize aryl ethers or aryl amines.[45][46]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hartwig, John F. (2012). "Borylation and Silylation of C–H Bonds: A Platform for Diverse C–H Bond Functionalizations". Accounts of Chemical Research. 45 (6): 864–873. doi:10.1021/ar200206a. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 22075137.

- ^ Cho, J. Y.; Tse, M. K.; Holmes, D.; Maleczka, R. E. Jr.; Smith, M. R. (2001). "Remarkably Selective Iridium Catalysts for the Elaboration of Aromatic C-H Bonds". Science. 295 (5553): 305–8. doi:10.1126/science.1067074. PMID 11719693. S2CID 21096755.

- ^ Ishiyama, T.; Nobuta, Y.; Hartwig, J. F.; Miyaura, N. Chem. Commun. 2003, 2924.

- ^ Brown, H. C.; Kramer, G. W.; Levy, A. B.; Midland, M. M. Organic Synthesis via Boranes; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1975; Vol. 1.

- ^ Braunschweig, H.; Guethlein, F. (2011). "Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Synthesis of Diboranes(4)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (52): 12613–12616. doi:10.1002/anie.201104854. PMID 22057739.

- ^ Hall, D. G. (2011) Structure, Properties, and Preparation of Boronic Acid Derivatives, in Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis, Medicine and Materials (Volume 1 and 2), Second Edition (ed D. G. Hall), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany. doi:10.1002/9783527639328.ch1

- ^ Mkhalid, Ibraheem A. I.; Barnard, Jonathan H.; Marder, Todd B.; Murphy, Jaclyn M.; Hartwig, John F. (2010). "C–H Activation for the Construction of C–B Bonds". Chemical Reviews. 110 (2): 890–931. doi:10.1021/cr900206p. PMID 20028025.

- ^ Wade, L. G., Organic Chemistry. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc., 2010.

- ^ Chen, H.; Schlecht, S.; Semple, T. C.; Hartwig, J. F. (2000). "Thermal, Catalytic, Regiospecific Functionalization of Alkanes". Science. 287 (5460): 1995–1997. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.1995C. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1995. PMID 10720320.

- ^ Lawrence, J. D.; Takahashi, M.; Bae, C.; Hartwig, J. F. (2004). "Regiospecific Functionalization of Methyl C−H Bonds of Alkyl Groups in Reagents with Heteroatom Functionality". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (47): 15334–15335. doi:10.1021/ja044933x. PMID 15563132.

- ^ a b c Hartwig, J. F. (2011). "Regioselectivity of the borylation of alkanes and arenes". Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (4): 1992–2002. doi:10.1039/C0CS00156B. PMID 21336364.

- ^ Wei, C. S.; Jimenez-Hoyos, C. A.; Videa, M.F.; Hartwig, J. F.; Hall, M. B. (2010). "Origins of the Selectivity for Borylation of Primary over Secondary C−H Bonds Catalyzed by Cp*-Rhodium Complexes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (9): 3078–91. doi:10.1021/ja909453g. PMID 20121104.

- ^ Kondo, Y.; Garcia-Cuadrado, D.; Hartwig, J. F.; Boaen, N. K.; Wagner, N. L.; Hillmyer, M. A. (2002). "Rhodium-Catalyzed, Regiospecific Functionalization of Polyolefins in the Melt". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 (7): 1164–5. doi:10.1021/ja016763j. PMID 11841273.

- ^ Iverson, Carl N.; Smith, Milton R. (1999-08-06). "Stoichiometric and Catalytic B−C Bond Formation from Unactivated Hydrocarbons and Boranes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 121 (33): 7696–7697. doi:10.1021/ja991258w.

- ^ a b Hartwig, J.F. (2012). "Borylation and silylation of C-H bonds: a platform for diverse C-H bond functionalizations". Accounts of Chemical Research. 45 (6): 864–873. doi:10.1021/ar200206a. PMID 22075137.

- ^ Ishiyama, T.; Takagi, J.; Ishida, K.; Miyaura, N.; Anastasi, N.; Hartwig, J.F. (2002). "Mild Iridium-Catalyzed Borylation of Arenes. High Turnover Numbers, Room Temperature Reactions, and Isolation of a Potential Intermediate". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 (3): 390–391. doi:10.1021/ja0173019. PMID 11792205.

- ^ Liskey, C. Iridium-Catalyzed Borylation of Aromatic and Aliphatic C–H bonds: Methodology and Mechanism. Dissertation, University of Illinois. Urbanan-Champaign. 2013.

- ^ Fischer, D.F; Sarpong, R. (2010). "Total Synthesis of (+)-Complanadine A Using an Iridium-Catalyzed Pyridine C−H Functionalization". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (17): 5926–5927. doi:10.1021/ja101893b. PMC 2867450. PMID 20387895.

- ^ Boebel, T. A.; Hartwig, J. F. (2008). "Silyl-Directed, Iridium-Catalyzedortho-Borylation of Arenes. A One-Potortho-Borylation of Phenols, Arylamines, and Alkylarenes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (24): 7534–5. doi:10.1021/ja8015878. PMID 18494474.

- ^ Ishiyama, T.; Miyaura, N.; Isou, H.; Kikuchi, T. (2010). "Ortho-C–H borylation of benzoate esters with bis(pinacolato)diboron catalyzed by iridium–phosphine complexes". Chem. Commun. 46 (1): 159–61. doi:10.1039/b910298a. hdl:2115/44631. PMID 20024326.

- ^ Kawamorita, S.; Ohmiya, H.; Hara, K.; Fukuoka, A.; Sawamura, M. (2009). "Directed Ortho Borylation of Functionalized Arenes Catalyzed by a Silica-Supported Compact Phosphine−Iridium System". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (14): 5058–9. doi:10.1021/ja9008419. PMID 19351202.

- ^ Ros, A.; Estepa, B.; Lopez-Rodriquez, R.; Alvarez, E.; Fernandez, R.; Lassaletta, J.M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011; 50, 1.

- ^ Boller, T.M.; Murphy, J. M.; Hapke, M.; Ishiyama, T.; Miyaura, N.; Hartwig, J.F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;, 127, 14263.

- ^ Boebel, T.A.; Hartwig, J.F. (2008). "Silyl-Directed, Iridium-Catalyzedortho-Borylation of Arenes. A One-Potortho-Borylation of Phenols, Arylamines, and Alkylarenes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (24): 7534–7535. doi:10.1021/ja8015878. PMID 18494474.

- ^ Bisht, R.; Chattopadhyay, B. (2016). "Formal Ir-Catalyzed Ligand-Enabled Ortho and Meta Borylation of Aromatic Aldehydes via in Situ-Generated Imines". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (1): 84–7. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b11683. PMID 26692251.

- ^ Kanai; et al. (2015). "A meta-selective C–H borylation directed by a secondary interaction between ligand and substrate". Nat. Chem. 7 (9): 712–7. Bibcode:2015NatCh...7..712K. doi:10.1038/nchem.2322. PMID 26291942.

- ^ Hirao, Akira; Itsuno, Shinichi; Nakahama, Seiichi; Yamazaki, Noboru (1981). "Asymmetric reduction of aromatic ketones with chiral alkoxy-amineborane complexes". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (7): 315. doi:10.1039/c39810000315.

- ^ Corey, E. J.; Bakshi, Raman K.; Shibata, Saizo (September 1987). "Highly enantioselective borane reduction of ketones catalyzed by chiral oxazaborolidines. Mechanism and synthetic implications". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 109 (18): 5551–5553. doi:10.1021/ja00252a056.

- ^ Corey, E. J.; Bakshi, Raman K.; Shibata, Saizo; Chen, Chung Pin; Singh, Vinod K. (December 1987). "A stable and easily prepared catalyst for the enantioselective reduction of ketones. Applications to multistep syntheses". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 109 (25): 7925–7926. doi:10.1021/ja00259a075.

- ^ Midland, M.Mark; Tramontano, Alfonso; Zderic, Stephen A (July 1977). "The facile reaction of B-alkyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes with benzaldehyde". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 134 (1): C17–C19. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)93625-8.

- ^ Midland, M. Mark; Tramontano, Alfonso; Zderic, Stephen A. (June 1977). "Preparation of optically active benzyl-.alpha.-d alcohol via reduction by B-3.alpha.-pinanyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane. A new highly effective chiral reducing agent". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 99 (15): 5211–5213. doi:10.1021/ja00457a068.

- ^ Ramesh, D.; Shekhar, V.; Chantibabu, D.; Rajaram, S.; Ramulu, U.; Venkateswarlu, Y. (March 2012). "First stereoselective total synthesis of pectinolide H". Tetrahedron Letters. 53 (10): 1258–1260. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.12.122.

- ^ Petasis, Nicos A.; Akritopoulou, Irini (January 1993). "The boronic acid mannich reaction: A new method for the synthesis of geometrically pure allylamines". Tetrahedron Letters. 34 (4): 583–586. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)61625-8.

- ^ Yu, Tao; Li, Hui; Wu, Xinyan; Yang, Jun (2012). "Progress in Petasis Reaction". Chinese Journal of Organic Chemistry. 32 (10): 1836. doi:10.6023/cjoc1202092.

- ^ Herold, Thomas; Hoffmann, Reinhard W. (October 1978). "Enantioselective Synthesis of Homoallyl Alcoholsvia Chiral Allylboronic Esters". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 17 (10): 768–769. doi:10.1002/anie.197807682.

- ^ Roush, William R.; Walts, Alan E.; Hoong, Lee K. (December 1985). "Diastereo- and enantioselective aldehyde addition reactions of 2-allyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane-4,5-dicarboxylic esters, a useful class of tartrate ester modified allylboronates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 107 (26): 8186–8190. doi:10.1021/ja00312a062.

- ^ Roush, William R.; Ando, Kaori; Powers, Daniel B.; Halterman, Ronald L.; Palkowitz, Alan D. (January 1988). "Enantioselective synthesis using diisopropyl tartrate modified (E)- and (Z)-crotylboronates: Reactions with achiral aldehydes". Tetrahedron Letters. 29 (44): 5579–5582. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)80816-3.

- ^ Roush, William R.; Grover, Paul T. (January 1990). "Diisopropyl tartrate (E)-γ-(dimethylphenylsilyl)allylboronate, a chiral allylic alcohol β-carbanion equivalent for the enantioselective synthesis of 2-butene-1,4-diols from aldehydes". Tetrahedron Letters. 31 (52): 7567–7570. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97300-3.

- ^ Roush, William R.; Gover, Paul T.; Lin, Xiaofa (January 1990). "Diisopropyl tartrate modified (E)-γ-[(cyclohexyloxy)dimethylsilyl-allylboronate, a chiral reagent for the stereoselective synthesis of anti 1,2-diols via the formal α-hydroxyallylation of aldehydes". Tetrahedron Letters. 31 (52): 7563–7566. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97299-X.

- ^ Fernandes, Rodney A.; Kattanguru, Pullaiah (November 2011). "Total synthesis of (8S,11R,12R)- and (8R,11R,12R)-topsentolide B2 diastereomers and assignment of the absolute configuration". Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 22 (20–22): 1930–1935. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2011.10.020.

- ^ Miyaura, Norio; Suzuki, Akira (1979). "Stereoselective synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes by the reaction of alk-1-enylboranes with aryl halides in the presence of palladium catalyst". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (19): 866. doi:10.1039/C39790000866.

- ^ Miyaura, Norio; Yamada, Kinji; Suzuki, Akira (January 1979). "A new stereospecific cross-coupling by the palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboranes with 1-alkenyl or 1-alkynyl halides" (PDF). Tetrahedron Letters. 20 (36): 3437–3440. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)95429-2. hdl:2115/44006.

- ^ Nemecek, Gregor; Thomas, Robert; Goesmann, Helmut; Feldmann, Claus; Podlech, Joachim (October 2013). "Structure Elucidation and Total Synthesis of Altenuic Acid III and Studies towards the Total Synthesis of Altenuic Acid II". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2013 (28): 6420–6432. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300879.

- ^ Kürti, László; Czakó, Barbara (2007). Strategic applications of named reactions in organic synthesis : background and detailed mechanisms ; 250 named reactions (Pbk. ed., [Nachdr.]. ed.). Amsterdam [u.a.]: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 464–465. ISBN 978-0-12-429785-2.

- ^ Quach, Tan D.; Batey, Robert A. (April 2003). "Copper(II)-Catalyzed Ether Synthesis from Aliphatic Alcohols and Potassium Organotrifluoroborate Salts". Organic Letters. 5 (8): 1381–1384. doi:10.1021/ol034454n. PMID 12688764.

- ^ Quach, Tan D.; Batey, Robert A. (1 November 2003). "Ligand- and Base-Free Copper(II)-Catalyzed C−N Bond Formation: Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organoboron Compounds with Aliphatic Amines and Anilines". Organic Letters. 5 (23): 4397–4400. doi:10.1021/ol035681s. PMID 14602009.