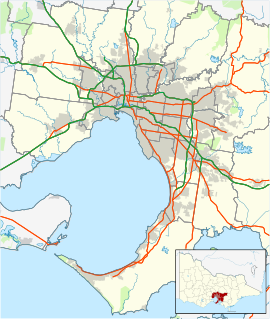

Sunshine is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 12 km (7.5 mi) west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Brimbank local government area. Sunshine recorded a population of 9,445 at the 2021 census.[1]

| Sunshine Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sunshine town centre | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°46′52″S 144°49′55″E / 37.781°S 144.832°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 9,445 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,928/km2 (4,990/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3020 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 42 m (138 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 4.9 km2 (1.9 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 12 km (7 mi) from Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Brimbank | ||||||||||||||

| County | Bourke | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Laverton | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Fraser | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Sunshine, initially a town just outside Melbourne, is today a residential suburb with a mix of period and post-War homes, with a town centre that is an important retail centre in Melbourne's west. It is also one of Melbourne's principal places of employment outside the CBD with many industrial companies situated in the area, and is an important public transport hub with both V/Line and Metro services at Sunshine railway station and its adjacent major bus interchange.

History

edit19th century

editThe farms and settlements in the area now known as Sunshine first came under the Sunshine Road District (1860–1871) which later became the Shire of Braybrook (1871–1951).[2]

From 1860 to 1885 the only railway which passed through the area was the Bendigo line and the only railway station in the area was Albion & Darlington (opened 5 January 1860) at the site of the current Albion station. When the Ballarat line was built through the area, a new station was built at the junction of the two lines: this station opened on 7 September 1885 and was called Braybrook Junction as it was in the Shire of Braybrook.

The area around the Braybrook Junction railway station then came to be known as Braybrook Junction. The Braybrook Junction Post Office opened on 25 August 1890.[3]

20th century

editPre-war Sunshine

editIn 1904 H. V. McKay bought a factory in the area called the Braybrook Implement Works. He also secured 400 acres (160 ha) of land at Braybrook Junction with the aim of establishing housing to allow his future workers to live in the area, along the lines of a company town. The land became the Sunshine Estate (see below).[4]

In 1906 McKay moved his agricultural machinery manufacturing business from Ballarat to his newly acquired factory in Braybrook Junction. The factory was renamed the Sunshine Harvester Works and it became the largest manufacturing plant in Australia.

In July 1907, the train station, the post office, and the shire riding's names were changed from Braybrook Junction to Sunshine after workers and residents had petitioned to do so in honour of McKay's Sunshine Harvester Works.[5][6][2]

Also in 1907 an industrial dispute between owner H. V. McKay and his workers at the Sunshine Harvester Works led to the Harvester Judgement, the benchmark industrial decision which led to the creation of a minimum living wage for Australian workers.[2]

The Sunshine train disaster on 20 April 1908 killed 44 people at Sunshine station.[7]

In 1909, the H. V. McKay Sunshine Harvester Works Pipe Band was formed. This is one of Australia's oldest continuously functioning pipe bands and still exists as the Victoria Scottish Pipes & Drums.[8]

Prue McGoldrick's My Paddock: An Early Twentieth Century Childhood is a memoir of growing up in Sunshine.[9][10]

The Sunshine Estate and H. V. McKay's civic works

editThe land that H. V. McKay had earlier purchased to build housing for his workers on was developed by McKay as the Sunshine Estate.[11][12] This housing estate was developed with superficial similarity to some street plans of cities created by followers of the Garden city movement, an influential town planning movement of the early 20th century. Infrastructure and amenities established by McKay for the Sunshine Estate and the rest of Sunshine included electric street lighting, parks and sporting grounds, public buildings, schools, and a library. The town of Sunshine (not a suburb of Melbourne at this point) became regarded as a model industry-centred community.[13] Housing for the McKay's employees swelled the local population and the town of Sunshine was touted as the "Birmingham of Australia".[14]

Post-war Sunshine

editAfter WWII, Sunshine increasingly became connected to the sprawling city of Melbourne as car-based travel enabled people to leave the inner city suburbs and move into houses on larger blocks in suburbia. In 1951, the old Shire of Braybrook was abolished and the City of Sunshine was established.[15]

Sunshine was not immune when many Australian-based manufacturing industries started winding down during and after the 1970s. In 1992, the Massey Ferguson factory, formerly the Sunshine Harvester Works, was demolished to make way for the development of the Sunshine Marketplace.[16]

On 15 December 1994, the City of Sunshine was abolished and Sunshine became part of the newly created City of Brimbank.[17]

21st century

editSunshine is now both a low-density residential suburb and one of Melbourne's principal places of employment outside the CBD. Many heavy and light industrial companies are situated in and around the area and it is an important retail centre in Melbourne's west. In addition to Sunshine's street shopping strips there are two shopping centres, the Sunshine Plaza and the Sunshine Marketplace. There is a Village Cinemas multiplex, the "Village 20 Sunshine Megaplex", at the Sunshine Marketplace.[18]

Educational institutions in Sunshine include Victoria Polytechnic (the TAFE division of Victoria University). Secondary schools include Sunshine College and Harvester Technical College.[19]

Demographics

editSunshine is a highly multicultural suburb. In the post-WWII period, many immigrants from all over continental Europe settled in Sunshine. Today Sunshine still has significant populations from Italy, Greece, the former Yugoslavia, and Poland. It is also the main centre for Melbourne's Maltese community:[20] indeed, the only branch of Malta's Bank of Valletta in the whole of Oceania is situated on Watt Street, Sunshine.

From the late 1970s, many Vietnamese refugees settled in Sunshine and surrounding areas. The Vietnamese have opened small businesses such as groceries and restaurants throughout the Sunshine town centre. More recently, immigrants moving to Sunshine have come from Sudan, Burma and India.[21]

In 2016, Sunshine had a population of 9,768. The most common ancestries given in the 2016 census were: Australian 11.4%, English 12.5%, Vietnamese 12.9%, Chinese 5.9% and Irish 5.0%. For country of birth, 42% of people were born in Australia while the other most common countries of birth were Vietnam with 12.6%, India 5.7%, Burma 4.0%, Philippines 2.0%, and Nepal 2.0%.[21]

Transport

editSunshine railway station was completely redeveloped as part of the Regional Rail Link. Works began in 2012 and were complete by mid-2014. It is both a suburban Metro station and an interchange for V/Line (regional) passenger services. Classed as a Premium station,[22] it is in the PTV zones 1+2 overlap.[23]

Sunshine station is one of Victoria's most important regional rail hubs: all three of the main western region V/Line lines (Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong) meet at Sunshine. Geelong services have stopped at Sunshine since the opening of the Regional Rail Link in 2015.[24] The Sydney to Melbourne XPT passes through Sunshine, as it uses the Albion–Jacana railway line, but it does not stop there.

Sunshine also has one of Melbourne's major suburban bus interchanges, which was upgraded as part of the Regional Rail Link works in 2014. This is situated directly adjacent to the Sunshine Railway Station.

In a 2018 study Sunshine was named one of the 20 most walkable suburbs in Melbourne's middle suburbia.[25]

Cyclists in Sunshine are represented by BrimBUG, the Brimbank Bicycle User Group.[26]

Community facilities

editHue Quang Temple, a Vietnamese Buddhist temple, is located in the suburb.[27]

Sport and leisure

editThe heritage-listed H.V. McKay Memorial Gardens on Anderson Road, established in 1909 by H.V. McKay as Sunshine Gardens, is one of two remaining "industrial gardens" in Australia.[28][29]

The Kororoit Creek runs through Sunshine, along which runs the Kororoit Creek Trail for walking and cycling.

The Sunshine Football Club, the Sunshine Kangaroos, are the local Australian Rules football team.[30] They compete in the Western Region Football League.[31]

The Sunshine Cricket Club, the Sunshine Crows, is based at Dempster Park in North Sunshine.[32]

The Sunshine Park Tennis Club is based at Parsons Reserve Sunshine.[33]

Sunshine Cowboys play rugby league in NRL Victoria.

The Sunshine George Cross Football Club, the Sunshine Georgies, are the local Victorian Premier League soccer team. Their home ground is Chaplin Reserve on Anderson Road.

The Sunshine Baseball Club, the Sunshine Eagles, have their baseball field in Barclay Reserve on Talmage Street, Albion.[34]

Golfers play at the course of the Sunshine Golf Club on Mt Derrimut Road, Derrimut. It relocated from the Fitzgerald Road course in November 2007.[35]

Notable residents

edit- Leigh Bowery, London-based avant-garde artist and designer.[36]

- Doug Chappel, comedian, actor.

- Lester Ellis, former World champion boxer. Grew up in West Sunshine.

- Reverend John Flynn, the Presbyterian minister and aviator who founded the Royal Flying Doctor Service and who is featured on the current Australian twenty-dollar note.[2]

- Charles Greenwood, pastor who revived the Assemblies of God church in Australia.

- John Kelly, artist who grew up in Sunshine.[37]

- Lydia Lassila, freestyle skier and 2010 Winter Olympic gold medallist who grew up and went to school in Sunshine.[38]

- Hugh Victor McKay, leading Australian industrialist of the early 20th century; founder of the Sunshine Harvester Works.[2]

- Keith Miller, Australian Cricket Hall of Famer of the 1940s and 50s. Born in Sunshine.[2]

- Craig Parry, one of Australia's premier golfers. Born in Sunshine.

- Walter "Wally" Peeler, WWI soldier, Victoria Cross and British Empire Medal winner and first custodian of the Shrine of Remembrance.

- Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, who had an extended stay at the Derrimut Hotel in 1945.[39]

- Bon Scott, lead singer of AC/DC who lived in Sunshine as a child.[40]

- Stelarc, Cypriot-born, Sunshine-raised performance artist.[18]

- Richard Tyler, born 1947, fashion designer in New York and Hollywood.[18]

- Cal Wilson, stand-up comedian and radio and television personality.[41]

In popular culture

edit- The disused former Albion Quarrying Company site, accessed from Hulett Street, Sunshine was the location for AC/DC's 1976 Jailbreak music video.[40][42]

- In the 1997 film The Castle, the Kerrigans' daughter Tracey obtained her hairdressing qualification from Sunshine TAFE.

- In the television series Kath & Kim, Kath Day-Knight has obtained numerous qualifications from Sunshine TAFE.

- Sunshine is the setting of the 2007 film Noise.

- Sunshine and surrounding suburbs are the principal settings of the 2017 SBS drama series Sunshine.

See also

edit- City of Sunshine – Sunshine was previously within this former local government area.

References

edit- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Sunshine (Vic.) (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Ford, Olwen (2001). Harvester Town: The making of Sunshine 1890–1925. Sunshine & District Historical Society Incorporated. ISBN 0-9595989-4-4.

- ^ "Post Office List", Phoenix Auctions History, retrieved 24 January 2021

- ^ "Sunshine Harvester Works – HV McKay – a history of agricultural enterprise in Victoria, Australia 1880–1960 – Factory", Museum Victoria, archived from the original on 21 April 2009, retrieved 25 August 2009

- ^ "Numurkah Leader". Trove. 2 August 1907. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Harvester Works – HV McKay – a history of agricultural enterprise in Victoria, Australia 1880–1960 – Sunshine", Museum Victoria, archived from the original on 22 April 2009, retrieved 25 August 2009

- ^ Sunshine Rail Disaster – 100 years on, Brimbank Leader 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Band History". Victoria Scottish Pipes & Drums. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ McGoldrick, Prue (1994). My Paddock: An Early Twentieth Century Childhood. Morwell: Gippsland Printers. ISBN 9780959099423.

- ^ Campion, Edmund (2014). "Older, simpler days: Prue McGoldrick". Australian Catholic Lives. David Lovell Publishing. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9781863551458.

- ^ HO Selwyn Park BriMbank City Council

- ^ HO Sugar Gum row Brimbank City Council

- ^ "Sunshine – Place – eMelbourne – The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online". emelbourne.net.au.

- ^ "Developing Australia's Manufacturing Base" (PDF), City of Brimbank, retrieved 21 July 2009

- ^ "Sunshine (City 1951-1994)". Public Record Office Victoria online catalogue. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Harvester Works – HV McKay – a history of agricultural enterprise in Victoria, Australia 1880–1960 – Armchair Tour – McKay's Dream Machine". Museum Victoria. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (1 August 1995). Victorian local government amalgamations 1994-1995: Changes to the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. pp. 4, 8. ISBN 0-642-23117-6. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ a b c "In defence of Sunshine: Surprising facts you may not know about Melbourne's sunny suburb". Herald Sun. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Victoria University (2012). "Harvester Technical College". Victoria University. Victoria University. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Museum Victoria Australia (2012). "History of immigration from Malta". Museum Victoria Australia. Museum Victoria Australia. Archived from the original on 30 July 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Sunshine (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Regional train and coach network". Public Transport Victoria. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Railway Station (Sunshine)". ptv.vic.gov.au.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Jemimah Clegg; Melissa Heagney (20 October 2018). "Melbourne's most and least walkable suburbs". The Age. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "BrimBUG". brimbug.org.au.

- ^ "THÀNH VIÊN GIÁO HỘI". The Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation of Australia - New Zealand. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "HV McKay Memorial Gardens". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Council of Victoria. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Historical significance". Friends of McKay Gardens website. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Football Club". Sunshine Football Club official website. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Football Club", Australian Football, retrieved 9 September 2017

- ^ "Sunshine Cricket Club". Facebook. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Park Tennis Club Inc". Facebook. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Baseball Club". Sunshine Baseball Club. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sunshine Golf Club". Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Leigh Bowery". The National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Angus Livingston (12 February 2014). "Former Sunshine artist John Kelly wants to bring cows home to Brimbank". Herald Sun. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "SOCHI: Lydia Lassila aims for second Olympics gold". Melton & Moorabool Star Weekly. Fairfax Community Newspapers. 21 January 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Wright, Tony (11 June 2011). "A jolly good time in land of combine harvesters". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ a b Wall, Mick (2012). AC/DC: Hell Aint a Bad Place to Be. London: Orion Publishing group. ISBN 9781409115359.

- ^ Michael Lallo (11 February 2011). "Giggles for a cause". The Age. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Evans, Mark, Dirty Deeds: My Life Inside/Outside AC/DC, Bazillion Points, 2011