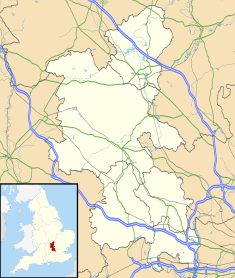

Buckingham Town Hall is a municipal building in the Market Square, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, England. The structure, which was the meeting place of Buckingham Borough Council, is a Grade II* listed building.[1]

| Buckingham Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Buckingham Town Hall | |

| Location | Market Square, Buckingham |

| Coordinates | 51°59′59″N 0°59′17″W / 51.9997°N 0.9880°W |

| Built | 1783 |

| Architectural style(s) | Georgian style |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Old Town Hall |

| Designated | 15 February 1996 |

| Reference no. | 1282685 |

History

editThe first town hall in Buckingham was erected in the Market Place on the initiative of the local member of parliament, Sir Ralph Verney in 1685.[1] When it became dilapidated in the mid-18th century, civic leaders decided to erect a new building slightly to the south of the original structure.[1][2]

The new building was designed in the Georgian style, built in red brick and was completed in 1783.[3] The design involved a symmetrical main frontage with five bays facing onto the Market Square; the central bay featured a round headed doorway with a fanlight; there were sash windows which were recessed in blank arcading on the ground floor and plain sash windows on the first floor.[1] On the left hand side, there was a semi-circular projection and, at roof level, there was a dentilled cornice and a turret with a finial surmounted by a copper swan, which recalled the coat of arms of the town.[1] Internally, the principal room was the assembly room on the first floor which had a high ceiling and was accessed using a fine staircase which had been recovered from the first town hall.[2]

The town became a municipal borough with the town hall as its headquarters in 1835.[4] After the 2nd Duke of Buckingham was declared bankrupt in 1847, the borough council acquired ownership of the building, albeit with a large mortgage.[5] The suffragettes, Lilias Ashworth, Lydia Becker and Helen Beedy, gave speeches advocating voting rights for women at a public meeting in the building chaired by future member of parliament, Egerton Hubbard, in October 1875.[6][7]

In 1882, an illuminated clock was inserted into the turret and, in 1885, the borough council paid off the mortgage that it had taken out to acquire the town hall.[5] In the early 20th century, the building was slightly shortened on the right hand side in order to facilitate the widening of Castle Street: this left a section of the cornice overhanging the street.[1] An iron canopy was erected above the main doorway at around the same time.[1]

The politician, Frank Markham, was lifted shoulder-high outside the town hall, after standing as the Conservative Party candidate and being elected member of parliament for the local constituency by a very small margin in the 1951 general election.[8] Another politician, Robert Maxwell, who had represented the Labour Party as the local member of parliament for six years, was so angry after losing his seat in the 1970 general election that he persuaded one of his supporters, Eleanor Berry, to climb onto the roof of the town hall and to wave the red flag.[9][10]

The town hall continued to serve as the headquarters of the borough council until 1965, when the council moved to Castle House on West Street.[11][12]

A Wurlitzer theatre organ with three manuals, which had been recovered from the Metropole Cinema in Victoria, London was installed in the town hall in 1963; however, after concerns were raised that it might cause structural damage to the building, it was transferred to the Assembly Hall in Worthing in 1981.[13][14] The ground floor, which had been occupied by a firm of estate agents, became home to a firm of solicitors in 2018.[15] Meanwhile, the assembly room continued to be used as an events venue.[16]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Historic England. "Old Town Hall (1282685)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b Page, William (1925). "'The borough of Buckingham', in A History of the County of Buckingham". London: British History Online. pp. 471–489. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Pevsner, Elizabeth; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1994). Buckinghamshire (Buildings of England Series). Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0300095845.

- ^ "Buckingham MB". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b "The Joy of being a Pocket Borough". Buckingham and Winslow Advertiser. 13 June 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Cartwright, Colin (2013). Burning to Get the Vote: The Women's Suffrage Movement in Central Buckinghamshire, 1904-1914. University of Buckingham Press. ISBN 978-1908684097.

- ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (2005). The Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland: A Regional Survey. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0415383325.

- ^ Close, Charles (2009). Buckingham Through Time. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1848687981.

- ^ Preston, John (2021). Fall: The mystery of Robert Maxwell. Viking. ISBN 978-0241388679.

- ^ Berry, Eleanor (2017). Come Sweet Sexton, Tend My Grave. Book Guild Publishing. ISBN 978-1911320265.

- ^ "National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949". London Gazette (43610): 3094. 26 March 1965. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

The Town Clerk's Office, Town Hall, Buckingham

- ^ "Boundary Commission for England". Bucks Examiner. Chesham. 17 September 1965. p. 18. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

Town Clerk's Office, Castle House, West Street, Buckingham

- ^ "Laurence James plays The 3/10 Kimball/Wurlitzer from the Buckingham Town Hall". Theatre Organs. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Jim Buckland". Cinema Organ Society. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Spratt Endicott move local office to new premises in heart of Buckingham". The Law Support Group. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Town Hall". Visitor UK. Retrieved 13 August 2021.