Christianity is the largest religion in Ghana, with 71.3% of the population belonging to various Christian denominations as of 2021 census.[2] Islam is practised by 19.9% of the total population. According to a report by the Pew Research, 51% of Muslims are followers of Sunni Islam, while approximately 16% belong to the Ahmadiyya movement and around 8% identify with Shia Islam, while the remainder are non-denominational Muslims.[3][4]

Religion in Ghana (2021 census)[1]

Ghana is a secular state and the country's constitution guarantees freedom of religion and worship. Christmas and Easter are recognized as national holidays.[4]

Overview

editThe largest Christian affiliations in the 2021 census were Pentecostal/charismatic (31.6% of the population) and Protestant (17.4%). According to a report by the Pew Research, 51% of Muslims are followers of Sunni Islam, while approximately 16% belong to the Ahmadiyya movement and around 8% identify with Shia Islam, while the remainder are non-denominational Muslims.[3][4]

Christian celebrations of Christmas and Easter are recognized as national holidays. In the past, vacation periods have been planned around these occasions, thus permitting both Christians and others living away from home to visit friends and family in the rural areas. Ramadan, the Islamic month of fasting, is observed by Muslims and traditional occasions are celebrated. These festivals include the Adae, which occur fortnightly, and the annual Odwira festivals. There is the annual Apoo festival activities, which is a kind of Mardi Gras and is held in towns.[4]

There is "no significant link between ethnicity and religion in Ghana" in 2022.[5]

Statistics

edit| Christian | Muslim | Traditional | Other | No religion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Pentecostal/ charismatic |

Other Protestant | Catholic | Other Christian | |||||

| 2000[8] | |||||||||

| 2010[9] | |||||||||

| 2021[10] | |||||||||

Christianity

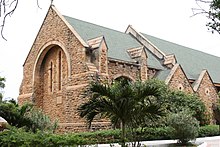

editThe presence of Christian missionaries on the coast has been dated to the arrival of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century. It was the Basel/Presbyterian and Wesleyan/Methodist missionaries, who, in the nineteenth century, laid the foundation for the Christian church in Ghana. They began their conversions in the coastal area as "nurseries of the church" in which an educated African class was trained. There are secondary schools, including exclusively boys and girls schools, that are mission- or church-related institutions. Church schools have been opened to all since the state assumed financial responsibility for formal instruction under the Education Act of 1960.[11]

Christian denominations are represented, including Evangelical Presbyterian and Catholicism.[11] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), in addition to chapels, has a temple in Accra. A second temple has been announced for the city of Kumasi.[12]

The unifying organization of Christians in the country is the Ghana Christian Council, founded in 1929. Representing the Methodist, Anglican, Mennonite, Presbyterian, Evangelical Presbyterian, African Methodist Episcopal Zionist, Methodist Church Ghana, Evangelical Lutheran, and Baptist churches, and the Society of Friends, the council serves as the link with the World Council of Churches and other ecumenical bodies. The Seventh-day Adventist Church, which is not a member of the Christian Council, has a presence also. The Church opened the premier private and Christian University.[11]

The National Catholic Secretariat, established in 1960, coordinates the in-country dioceses. These Christian organizations, concerned primarily with the spiritual affairs of their congregations, have occasionally acted in circumstances described by the government as political. Such was the case in 1991 when both the Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Christian Council of Ghana called on the military government of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) to return the country to constitutional rule. The Roman Catholic newspaper, The Standard, was critical of government policies.[11][13]

A 2015 study estimated that there are 50,000 Christians from a Muslim background in the country, though not all of them are necessarily citizens.[14]

A phenomenon among Christians is the end-of-year prophecies by religious leaders. Followers are keen to hear what the coming year holds. Some of these prophecies centre on the death of a person or the result of keenly contested national elections.[15][16][17]

Syncretic religion

editThe rise of Apostolic or Pentecostal churches across the nation partly demonstrates the impact of social change and the eclectic nature of traditional cultures. Some establishments have drum societies and singing groups and the independent African and Pentecostal churches reflected in figures for membership that rose from 1 and 2 percent, respectively, in 1960, to 14 and 8 percent, respectively, according to a 1985 estimate.[18]

Islam

editIslam made its entry into the northern territories of modern Ghana around the fifteenth century. Berber traders and clerics carried the religion into the area.[11] Most Muslims in Ghana are Sunni, following the Maliki school of jurisprudence.[19]

Those following the Maliki version of Islamic law and Sufism, involving the organization of mystical brotherhoods (tariq) for the purification and spread of Islam, is "not widespread".[clarification needed] The Tijaniyah and the Qadiriyah brotherhoods are represented. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, a religion originating in nineteenth-century India, is the only non-Sunni order.[11]

Guided by the authority of the Muslim Representative Council, religious, social, and economic matters affecting Muslims have been redressed through negotiations. The Muslim Council has been responsible for arranging pilgrimages to Mecca for believers who can afford the journey. There remains a gap between Muslims and Christians in Ghana. As society in Ghana modernized, Muslims were blocked from taking part in the modernization process. This is largely because access to jobs required Western education, and this education was only available in missionary schools. Many Muslims feared that sending their children to missionary schools may result in religious conversion.[20]

Traditional religion

editTraditional religions in Ghana have retained their influence because of their intimate relation to family loyalties and local mores. The traditional cosmology expresses belief in a supreme being referred as [Nyogmo - Ga, Mawu - Dangme and Ewe, Nyame -Twi] and the supreme being is usually thought of as remote from daily religious life and is, therefore, not directly worshipped.[18][21]

There are also the lesser gods that take "residency" in streams, rivers, trees, and mountains. These gods are generally perceived as intermediaries between the supreme being and society. Ancestors and numerous other spirits are also recognized as part of the cosmological order.[18] The spirit world is considered to be as real as the world of the living. The dual worlds of the mundane and the sacred are linked by a network of mutual relationships and responsibilities. The action of the living, for example, can affect the gods or spirits of the departed, while the support of family ancestors ensures prosperity of the lineage or state.[18]

Veneration of departed ancestors is a major characteristic of all traditional religions. The ancestors are believed to be the most immediate link with the spiritual world, and they are thought to be constantly near, observing every thought and action of the living.[18] To ensure that a natural balance is maintained between the world of the sacred and that of the profane, the roles of the family elders in relation to the lineage within society are crucial. The religious functions, especially lineage heads, are clearly demonstrated during such periods as the Odwira, Homowo, or the Aboakyir festivals, that are organized in activities that renew and strengthen relations with ancestors.[18]

Witchcraft

editPopular religions in Ghana such as Christianity and Islam coexist with the beliefs of spirits, evil, and witchcraft illustrated in traditional beliefs. There is an intersection of religion brought through colonization and existing precolonial beliefs related to witchcraft. In predominantly Christian communities, it is common to find articles and news on what "good" Christians can do to fight evil forces of witchcraft.[22]

The topic of witchcraft is often brought up in songs, and is present in the music culture in Ghana. Hearing about the topic through music adds to its broader relevance in its culture. Sang in Akan, the dominant non-English language in Ghana, popular songs reference witchcraft as explanation for things such as infertility, alcoholism, and death.[22] Details of witch beliefs and the nocturnal lives of witches are depicted in letters and local newspapers across Ghana. Witchcraft accusations are commonly seen through various forms of media including television, newspaper, and magazines.[22]

There are at least six witch camps in Ghana, housing a total of approximately 1,000 women.[23] Women suspected of being witches sometimes flee to witch camp settlements for safety, often in order to avoid being lynched by neighbours.[24][25]

Rastafarian religion

editThe Rastafari movement is a movement that arose in Jamaica in the 1930s. Its adherents worship Haile Selassie I, Emperor of Ethiopia (1930–1974), as God incarnate, the Second Advent, or the reincarnation of Jesus. According to beliefs, Haile Selassie was the 225th in an unbroken line of Ethiopian monarchs of the Solomonic Dynasty. This dynasty is said to have been founded in the 10th century BC by Menelik I, the son of the Biblical King Solomon and Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, who had visited Solomon in Israel.[26]

The Rastafari movement encompasses themes such as the spiritual use of cannabis and the rejection of western society, called 'Babylon'. It proclaims Africa, also known as 'Zion' as the original birthplace of mankind. Another theme is Royalty, with Rastas seeing themselves as African royalty and using honorifics such as Prince or King in order to give royalty to their names.

Many Rastas say that it is not a "religion" at all, but a "Way of Life". Rastafari are generally monotheists, worshipping a singular God whom they call Jah. Rastas see Jah as being in the form of the Holy Trinity, that is, Father, Son and the Holy Spirit. Rastas say that Jah, in the form of the Holy Spirit, lives within the human.

Afrocentrism is another central facet of the Rastafari culture. They teach that Africa, in particular Ethiopia, is where Zion, or paradise, shall be created. As such, Rastafari orients itself around African culture. Rastafari holds that evil society, or "Babylon", has always been white-dominated, and has committed such acts of aggression against the African people as the Atlantic slave trade. Despite this Afrocentrism and focus on people of the black race, members of other races, including whites, are found and accepted by Blacks among the movement, for they believe Rasta is for all people.

There are Rasta communities all around the world. In Ghana, particularly in the coast, there are many Rastafari places of worship. The Rasta community around Kokrobite is well known throughout Ghana. Many Rasta music festivals occur and Rasta objects are sold.

Hinduism

editHinduism has been practised in Ghana since 1970s. It was established by a traditional Priest known as Kwesi Esel who travelled to Asia to seek healing powers.[27] Hinduism is spread in Ghana actively by Ghana's Hindu Monastery headed by Swami Ghananand Saraswati and Hare Krishnas. Sathya Sai Organisation, Ananda Marga and Brahma Kumaris are also active in Ghana. Hindu temples have been constructed in Accra.

Afrikania Mission

editAfrikania Mission is a Neo-Traditional Movement established in Ghana in 1982 by a former Catholic Priest, Kwabena Damuah, who resigned from the church and assumed the traditional priesthood titles, Osofo Okomfo. The Mission aims to reform and update African traditional religion, and to promote nationalism and Pan-Africanism. Rather than being a single new religious movement, Afrikania also organizes various traditional shrines and traditional healers into associations bringing unity to a diffused system and thereby a greater voice in the public arena. Afrikania has instituted an annual convention for the traditional religion.

It has become a mouthpiece of traditional religion in Ghana through its publications, lectures, seminars, press conferences, and radio and television broadcast in which it advocates a return to traditional religion and culture as the spiritual basis for the development of Africa. The Mission is also known by other names such as AMEN RA (derived from Egyptian religion, and interpreted to mean 'God Centred'), Sankofa faith (implying a return to African roots for spiritual and moral values) and Godian Religion, which it adopted briefly during a period of association with Godianism, a Nigerian-based neo-traditional Movement.

Buddhism

editIn 1998 the first Nichiren Shoshu Temple in Africa was opened in Accra. Ghana has the largest Nichiren Shoshu Temple outside of Japan. The temple is located at Anyaa-Ablekuma Road at the Fan Milk Junction in Accra. There are other small Buddhist prayer spaces in larger cities.

Irreligion

editAtheism and Agnosticism are difficult to measure in Ghana.

Freedom of religion

editFreedom of religion exists in Ghana. A Religious Bodies (Registration) Law 1989 was passed in June 1989 to regulate churches. By requiring certification of all Christian religious organizations operating in Ghana, the government reserved the right to inspect the functioning of these bodies and to order the auditing of their financial statements. The Ghana Council of Churches interpreted the Religious Bodies Law as contradicting the concept of religious freedom in the country. According to a government statement, however, the law was designed to protect the freedom and integrity of genuine religious organizations by exposing and eliminating groups established to take advantage of believers. The PNDC repealed the law in late 1992. Despite its provisions, all orthodox Christian denominations and many spiritual churches continued to operate in the country.[18]

In 2023, the country was scored 3 out of 4 for religious freedom.[28]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2021 PHC General Report Vol 3C, Background Characteristics" (PDF). Ghana Statistical Service.

- ^ "2021 PHC General Report Vol 3C, Background Characteristics" (PDF). Ghana Statistical Service.

- ^ a b The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity (PDF) (Report). Pew Research Center, Forum on Religious & Public life. August 9, 2012. pp. 29–31. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Owusu-Ansah (1994), "Religion and Society".

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2022 Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor". USA state.gov. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Larabanga Mosque". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2024-02-03.

- ^ William (2018-07-24). "Ghana's Historic Mosques: Larabanga". The Hauns in Africa. Retrieved 2024-02-03.

- ^ "Adherent Statistics of World Religions by Country". ReligionFacts.

- ^ "Ghana". The World Factbook.

- ^ "2021 PHC General Report Vol 3C, Background Characteristics" (PDF). Ghana Statistical Service.

- ^ a b c d e f Owusu-Ansah (1994), "Christianity and Islam in Ghana".

- ^ "Kumasi Ghana Temple". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ Hans Werner Debrunner, A history of Christianity in Ghana (Waterville Pub. House, 1967).

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "🔥NIGEL GAISIE 2020 Prophecies drops! Election results, Akufo-Addo's wife, Chris Attoh, its Dαngɛroʋs". www.ghananewssummary.com. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ "🔥 Rev Owusu Bempah full 2020 Prophecies! Top 2 Pastors & 2 Chiefs D£ATH pronounced". www.ghananewssummary.com. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ "Bishop Salifu Amoako also drops his 2020 Prophecies;Reveals Nana Addo will win election;gives margin". www.ghananewssummary.com. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Owusu-Ansah (1994), "Traditional Religion".

- ^ Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation retrieved 4 September 2013

- ^ Holger Weiss (2004), "Variations in the Colonial Representation of Islam and Muslims in Northern Ghana, ca. 1900-1930".

- ^ Max Assimeng, "Traditional religion in Ghana: a preliminary guide to research." Thought and Practice Journal: The Journal of the Philosophical Association of Kenya 3.1 (1976): 65-89.

- ^ a b c Mensah Adinkrah (2015), "Witchcraft Beliefs in Ghana", Witchcraft, Witches, and Violence in Ghana, Berghahn Books, pp. 53–107, doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qcswd.7, ISBN 978-1-78238-561-5

- ^ "Ghana witch camps: Widows' lives in exile". bbc.co.uk. BBC. 1 September 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Briggs, Philip; Connolly, Sean (5 December 2016). Ghana. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781784770341. Retrieved 14 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn (9 September 2012). "In Ghana's witch camps, the accused are never safe". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 November 2017 – via LATimes.com.

- ^ "Rastafarianism". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ Laumann, Dennis (2014-12-02). "Hindu Gods in West Africa: Ghanaian Devotees of Shiva and Krishna by Albert Kafui Wuaku (review)". Ghana Studies. 17 (1): 247–249. doi:10.1353/ghs.2014.0012. ISSN 2333-7168.

- ^ Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-03

Works cited

edit- Owusu-Ansah, David. "Society and Its Environment" (and subchapters). A Country Study: Ghana (La Verle Berry, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (November 1994). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain (See About the Country Studies / Area Handbooks Program)

Further reading

edit- Amanor, Kwabena Darkwa. "Pentecostal and charismatic churches in Ghana and the African culture: confrontation or compromise?." Journal of Pentecostal Theology 18.1 (2009): 123-140.

- Assimeng, Max. "Traditional religion in Ghana: a preliminary guide to research." Thought and Practice Journal: The Journal of the Philosophical Association of Kenya 3.1 (1976): 65-89.

- Atiemo, Abamfo Ofori. Religion and the inculturation of human rights in Ghana (A&C Black, 2013).

- Cogneau, Denis, and Alexander Moradi. "Borders that divide: Education and religion in Ghana and Togo since colonial times." Journal of Economic History 74.3 (2014): 694-729. online

- Dovlo, Elom. "Religion and the politics of Fourth Republican elections in Ghana" (1992, 1996)." (2006).

- Langer, Arnim. "The situational importance of ethnicity and religion in Ghana." Ethnopolitics 9.1 (2010): 9-29.

- Langer, Arnim, and Ukoha Ukiwo. "Ethnicity, religion and the state in Ghana and Nigeria: perceptions from the street." in Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2008) pp. 205-226. online

- Owusu-Ansah, David. "Society and Its Environment" (and subchapters). A Country Study: Ghana (La Verle Berry, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (November 1994).

- Venkatachalam, Meera. Slavery, Memory and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850–Present (Cambridge University Press, 2015), the religious history of the Anlo-Ewe peoples .