The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with Sinocentric and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. The specific issue is: The article is not only written from the perspective of Chinese Buddhism but also pays too overtly portrays the involvement of Central Asia. (June 2024) |

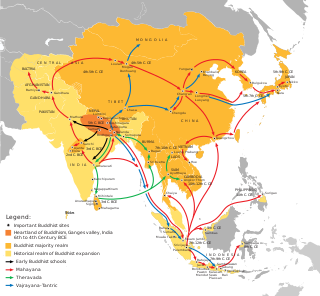

Mahāyāna Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[5][6] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE via the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory bordering the Tarim Basin under Kanishka.[7][8] These contacts transmitted strands of Sarvastivadan and Tamrashatiya Buddhism throughout the Eastern world.[9]

Theravada Buddhism developed from the Pāli Canon in Sri Lanka Tamrashatiya school and spread throughout Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Sarvastivada Buddhism was transmitted from North India through Central Asia to China.[9] Direct contact between Central Asian and Chinese Buddhism continued throughout the 3rd to 7th centuries, much into the Tang period. From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims like Faxian (395–414) and later Xuanzang (629–644) started to travel to northern India in order to get improved access to original scriptures. Between the 3rd and 7th centuries, parts of the land route connecting northern India with China was ruled by the Xiongnu, Han dynasty, Kushan Empire, the Hephthalite Empire, the Göktürks, and the Tang dynasty. The Indian form of Buddhist tantra (Vajrayana) reached China in the 7th century. Tibetan Buddhism was likewise established as a branch of Vajrayana, in the 8th century.[10]

But from about this time, the Silk road trade of Buddhism began to decline with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana (e.g. Battle of Talas), resulting in the Uyghur Khaganate by the 740s.[10] Indian Buddhism declined due to the resurgence of Hinduism and the Muslim conquest of India. Tang-era Chinese Buddhism was briefly repressed in the 9th century (but made a comeback in later dynasties). The Western Liao was a Buddhist Sinitic dynasty based in Central Asia, before Mongol invasion of Central Asia. The Mongol Empire resulted in the further Islamization of Central Asia. They embraced Tibetan Buddhism starting with the Yuan dynasty (Buddhism in Mongolia). The other khanates, the Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate, and Golden Horde eventually converted to Islam (Religion in the Mongol Empire#Islam).

Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Taiwanese and Southeast Asian traditions of Buddhism continued. As of 2019, China by far had the largest population of Buddhists in the world at nearly 250 million; Thailand comes second at around 70 million (see Buddhism by country).

Northern transmission

editThe Buddhism transmitted to China is based on the Sarvastivada school, with translations from Sanskrit to the Chinese languages and Tibetic languages.[9] These later formed the basis of Mahayana Buddhism. Japan and Korea then borrowed from China.[11] Few remnants of the original Sanskrit remained. These constituted the 'Northern transmission'.[9]

First contacts

editBuddhism entered[12] China via the Silk Road. Buddhist monks travelled with merchant caravans on the Silk Road to preach their new religion. The lucrative Chinese silk trade along this trade route began during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), with voyages by people like Zhang Qian establishing ties between China and the west.

Alexander the Great established Hellenistic kingdoms (323 BC – 63 BC) and trade networks extending from the Mediterranean to Central Asia (furthest eastern point being Alexandria Eschate). The Greco-Bactrian Kingdoms (250 BC-125 BC) in Afghanistan and the later Indo-Greek Kingdoms (180 BC-10 CE) formed one of the first Silk Road stops after China for nearly 300 years.[citation needed] One of the descendant Greek kingdoms, the Dayuan (Ta-yuan; Chinese: 大宛; "Great Ionians"), were defeated by the Chinese in the Han-Dayuan war. The Han victory in the Han–Xiongnu War further secured the route from northern nomads of the Eurasian Steppe.

The transmission of Buddhism to China via the Silk Road started in the 1st century CE with a semi-legendary account of an embassy sent to the West by the Chinese Emperor Ming (58–75 CE):

It may be assumed that travelers or pilgrims brought Buddhism along the Silk Roads, but whether this first occurred from the earliest period when those roads were open, ca. 100 BC, must remain open to question. The earliest direct references to Buddhism concern the 1st century AD, but they include hagiographical elements and are not necessarily reliable or accurate.[13]

Extensive contacts however started in the 2nd century CE, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Greco-Buddhist Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin, with the missionary efforts of a great number of Central Asian Buddhist monks to Chinese lands. The first missionaries and translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were either Parthian, Kushan, Sogdian or Kuchean.[14]

Missionaries

editIn the middle of the 2nd century, the Kushan Empire under king Kaniṣka from its capital at Purushapura (modern Peshawar), India expanded into Central Asia. As a consequence, cultural exchanges greatly increased with the regions of Kashgar, Khotan and Yarkand (all in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang). Central Asian Buddhist missionaries became active shortly after in the Chinese capital cities of Loyang and sometimes Nanjing, where they particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work. They promoted both Nikāya and Mahāyāna scriptures. Thirty-seven of these early translators of Buddhist texts are known.

- An Shigao, a Parthian prince who made the first known translations of Nikāya Buddhist texts into Chinese (148–170)

- Lokakṣema, a Kushan and the first to translate Mahāyāna scriptures into Chinese (167–186)

- An Xuan, a Parthian merchant who became a monk in China in 181

- Zhi Yao (c. 185), a Kushan monk in the second generation of translators after Lokakṣema.

- Zhi Qian (220–252), a Kushan monk whose grandfather had settled in China during 168–190

- Kang Senghui (247–280), born in Jiaozhi (or Chiao-chih) close to modern Hanoi in what was then the extreme south of the Chinese empire, and a son of a Sogdian merchant[15]

- Dharmarakṣa (265–313), a Kushan whose family had lived for generations at Dunhuang

- Kumārajīva (c. 401), a Kuchean monk and one of the most important translators

- Fotudeng (4th century), a Central Asian monk who became a counselor to the Chinese court

- Bodhidharma (440–528), the founder of the Chan (Zen) school of Buddhism. The debunked 17th century apocryphal story found in a manual called Yijin Jing claimed that he originated of the physical training of the Shaolin monks that led to the creation of Shaolin kung fu. This erroneous account only became popularized in the 20th century. According to the earliest reference to him, by Yang Xuanzhi, he was a monk of Central Asian origin whom Yang Xuanshi met around 520 at Loyang.[16] Throughout Buddhist art, Bodhidharma is depicted as a rather ill-tempered, profusely bearded and wide-eyed barbarian. He is referred to as "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" (碧眼胡:Bìyǎn hú) in Chinese Chan texts.[17]

- Five monks from Gandhāra who traveled in 485 CE to the country of Fusang ("the country of the extreme east" beyond the sea, probably Japan), where they introduced Buddhism.[a]

- Jñānagupta (561–592), a monk and translator from Gandhāra

- Prajñā (c. 810), a monk and translator from Kabul who educated the Japanese Kūkai in Sanskrit texts

Additionally, Indian monks from central regions of India were also involved in the translation and spread of Buddhists texts into central and east Asia.[18][19] Among these Indian translators and monks include:

- Dharmakṣema – 4th and 5th-century Buddhist monk from Magadha responsible for the translation of many Sanskrit texts in Chinese including the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra.

- Dhyānabhadra – 14th-century monk from Nalanda monastery who travelled to China and Korea during the period of the Yuan dynasty. Founded the Hoemsa temple in Korea.

- Guṇabhadra – 5th-century Mahayana Buddhist translator from Central India who was active in China

- Paramartha – 6th-century Indian monk and translator from Ujjain and patronised by Emperor Wu of Liang

Early translations into Chinese

editThe first documented translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese occurs in 148 CE with the arrival of the Parthian prince-turned-monk, An Shigao (Ch. 安世高). He worked to establish Buddhist temples in Luoyang and organized the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, testifying to the beginning of a wave of Central Asian Buddhist proselytism that was to last several centuries. An Shigao translated Buddhist texts on basic doctrines, meditation and abhidharma. An Xuan (Ch. 安玄), a Parthian layman who worked alongside An Shigao, also translated an early Mahāyāna Buddhist text on the bodhisattva path.

Mahāyāna Buddhism was first widely propagated in China by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema (Ch. 支婁迦讖, active ca. 164–186 CE), who came from the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Gandhāra. Lokakṣema translated important Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, as well as rare, early Mahāyāna sūtras on topics such as samādhi and meditation on the buddha Akṣobhya. These translations from Lokakṣema continue to give insight into the early period of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

By the 8th century CE, the School of Esoteric Buddhism became prominent in China due to the careers of two South Asian monks, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra. Vajrabodhi or Vajrabuddhi was the son of a South Indian aristocrat and is credited for bringing the theological developments from Bengal to East China. Buddhist scholar Lü Xiang, and lay disciple of Vajrabodhi writes about Vajrabodhi's accomplishments, including translating Buddhist texts such as ‘The Ritual for Practicing the Samadhi of Vairocana in the Yoga of the Adamantine Pinnacle Sutra’ etc.[1]

Though Vajrabodhi is credited for bringing Esoteric Buddhism into China, it was his successor, Amoghavajra, who saw the firm establishment of Esoteric Buddhism as a school of thought in China. Amoghavajra was the son of a South Asian father and Sodigan mother and brought his learnings from Sri Lanka to practice in China. He too translated several texts but is mostly known for this prominent position in the Royal Tang Court. Ge performed several Esoteric rituals for the royals and also established a separate doctrine of Buddhism for the deity Manjusri.[21]

Chinese pilgrims to India

editFrom the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel on the Silk Road to India, the origin of Buddhism, by themselves in order to get improved access to the original scriptures. According to Chinese sources, the first Chinese to be ordained was Zhu Zixing, after he went to Central Asia in 260 to seek out Buddhism.[22]

It is only from the 4th century CE that Chinese Buddhist monks started to travel to India to discover Buddhism first-hand. Faxian's pilgrimage to India (395–414) is said to have been the first significant one. He left along the Silk Road, stayed six years in India, and then returned by the sea route. Xuanzang (629–644) and Hyecho traveled from Korea to India.[23]

The most famous of the Chinese pilgrims is Xuanzang (629–644), whose large and precise translation work defines a "new translation period", in contrast with older Central Asian works. He also left a detailed account of his travels in Central Asia and India. The legendary accounts of the holy priest Xuanzang were described in the famous novel Journey to the West, which envisaged trials of the journey with demons but with the help of various disciples.

Role of merchants

editDuring the fifth and sixth centuries C.E., merchants played a large role in the spread of religion, in particular Buddhism. Merchants found the moral and ethical teachings of Buddhism to be an appealing alternative to previous religions. As a result, merchants supported Buddhist monasteries along the Silk Roads. In return, the Buddhists gave the merchants somewhere to sojourn. Merchants then spread Buddhism to foreign encounters as they travelled.[24] Merchants also helped to establish diaspora within the communities they encountered and over time, their cultures were based on Buddhism. Because of this, these communities became centers of literacy and culture with well-organized marketplaces, lodging, and storage.[25] The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism essentially ended around the 7th century with the invasion of Islam in Central Asia.

By the 8th century, Buddhism began to be spread across Asia, largely by the influence of healers and wonder-workers. These groups of people practised a form of Buddhism that was to be called "Vajrayana". This cult was influenced by the practice of Tantra in parts of India and would later go on to influence the East Asian society into adopting forms of Buddhism stemming from this core school of belief. This time, the transmission was happening via the sea routes.[26]

Decline of Buddhism in Central Asia and Xinjiang

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

Buddhism in Central Asia began to decline in the 7th century in the course of the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. After the Battle of Talas of 751, Central Asian Buddhism went into serious decline[27] and eventually resulted in the extinction of the local Tocharian Buddhist culture in the Tarim Basin during the 8th century.

The increasing Muslim dominance of these Silk Roads made it more difficult for Buddhist monks and pilgrims to travel between India and China.[28] The Silk Road transmission between Eastern Buddhism and Indian Buddhism eventually came to an end in the 8th century.

From the 9th century onward, therefore, the various schools of Buddhism which survived began to evolve independently of one another. Chinese Buddhism developed into an independent religion with distinct spiritual elements. Indigenous Buddhist traditions like Pure Land Buddhism and Zen emerged in China. China became the center of East Asian Buddhism, following the Chinese Buddhist canon, as Buddhism spread to Japan and Korea from China.[29] In the eastern Tarim Basin, Central Asian Buddhism survived into the later medieval period as the religion of the Uyghur Qocho Kingdom (see also Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves), and Buddhism became one of the religions in the Mongol Empire and the Chagatai Khanate, and via the Oirats eventually the religion of the Kalmyks, who settled at the Caspian in the 17th century. Otherwise, Central Asian Buddhism survived mostly in Tibet and in Mongolia.

Artistic influences

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

Central Asian missionary efforts along the Silk Road were accompanied by a flux of artistic influences, visible in the development of Serindian art from the 2nd to the 11th century CE in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. Serindian art often derives from the art of the Gandhāra district of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Highly sinicized forms of syncretism can also be found on the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin, such as in Dunhuang. Silk Road artistic influences can be found as far as Japan to this day, in architectural motifs or representations of Japanese gods.

Southern transmission (from Sri Lanka)

editThe Buddhism transmitted to Southeast Asia is based on the Tamrashatiya school based in Sri Lanka, with translations from Pali into languages like Thai, Burmese, etc. via the Pāli Canon.[9] These later formed the basis of Theravada Buddhism.[11] It is known as the Southern Transmission.[9]

Chinese historiography of Buddhism

editThe Book of the Later Han (5th century), compiled by Fan Ye (398–446 CE), documented early Chinese Buddhism. This history records that around 65 CE, Buddhism was practiced in the courts of both Emperor Ming of Han (r. 58–75 CE) at Luoyang (modern Henan); and his half-brother King Ying (r. 41–70 CE) of Chu at Pengcheng (modern Jiangsu). The Book of Han has led to discussions on whether Buddhism first arrived to China via maritime or overland transmission; as well as the origins of Buddhism in India or China.

Despite secular Chinese histories like the Book of Han dating the introduction of Buddhism in the 1st century, some Buddhist texts and traditions claim earlier dates in the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) or Former Han dynasty (208 BCE-9 CE).

Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE)

editOne story, first appearing in the (597 CE) Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀, concerns a group of Buddhist priests who arrived in 217 BCE at the capital of Qin Shi Huang in Xianyang (near Xi'an). The monks, led by the shramana Shilifang 室李防, presented sutras to the First Emperor, who had them put in jail:

But at night the prison was broken open by a Golden Man, sixteen feet high, who released them. Moved by this miracle, the emperor bowed his head to the ground and excused himself.[30]

The (668 CE) Fayuan Zhulin Buddhist encyclopedia elaborates this legend with Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great sending Shilifang to China.[31] Like Liang Qichao, some western historians believe Emperor Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to China, citing the (ca. 265) 13th Rock Edict that records missions to Greece, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.[32] Others disagree, "As far as we can gather from the inscriptions [Ashoka] was ignorant of the very existence of China."[33]

The Book of Han

editThe Book of the Later Han biography of Liu Ying, the King of Chu, gives the oldest reference to Buddhism in Chinese historical literature. It says Ying was both deeply interested in Huang-Lao 黄老 (from Yellow Emperor and Laozi) Daoism and "observed fasting and performed sacrifices to the Buddha."[34] Huang-Lao or Huanglaozi 黄老子 is the deification of Laozi, and was associated with fangshi (方士) "technician; magician; alchemist" methods and xian (仙) "transcendent; immortal" techniques.

"To Liu Ying and the Chinese devotees at his court the "Buddhist" ceremonies of fasting and sacrifices were probably no more than a variation of existing Daoist practices; this peculiar mixture of Buddhist and Daoist elements remains characteristic of Han Buddhism as a whole."[35]

In 65 CE, Emperor Ming decreed that anyone suspected of capital crimes would be given an opportunity for redemption, and King Ying sent thirty rolls of silk. The biography quotes Ming's edict praising his younger brother:

The king of Chu recites the subtle words of Huanglao, and respectfully performs the gentle sacrifices to the Buddha. After three months of purification and fasting, he has made a solemn covenant (or: a vow 誓) with the spirits. What dislike or suspicion (from Our part) could there be, that he must repent (of his sins)? Let (the silk which he sent for) redemption be sent back, in order thereby to contribute to the lavish entertainment of the upāsakas (yipusai 伊蒲塞) and śramaṇa (sangmen 桑門).[36][b]

In 70 CE, King Ying was implicated in rebellion and sentenced to death, but Ming instead exiled him and his courtiers south to Danyang (Anhui), where Ying committed suicide in 71 CE. The Buddhist community at Pencheng survived, and around 193 CE, the warlord Zhai Rong built a huge Buddhist temple, "which could contain more than three thousand people, who all studied and read Buddhist scriptures."[38]

Second, Fan Ye's Book of Later Han quotes a "current" (5th-century) tradition that Emperor Ming prophetically dreamed about a "golden man" Buddha. While "The Kingdom of Tianzhu" section (above) recorded his famous dream, the "Annals of Emperor Ming" history did not. Apocryphal texts give divergent accounts about the imperial envoys sent to India, their return with two Buddhist monks, Sanskrit sutras (including Sutra of Forty-two Chapters) carried by white horses, and establishing the White Horse Temple.

Maritime or overland transmission

editSince the Book of Later Han present two accounts of how Buddhism entered Han China, generations of scholars have debated whether monks first arrived via the maritime or overland routes of the Silk Road.

The maritime route hypothesis, favored by Liang Qichao and Paul Pelliot, proposed that Buddhism was originally introduced in southern China, the Yangtze River and Huai River region, where King Ying of Chu was worshipping Laozi and Buddha c. 65 CE. The overland route hypothesis, favored by Tang Yongtong, proposed that Buddhism disseminated eastward through Yuezhi and was originally practiced in western China, at the Han capital Luoyang where Emperor Ming established the White Horse Temple c. 68 CE.

The historian Rong Xinjiang reexamined the overland and maritime hypotheses through a multi-disciplinary review of recent discoveries and research, including the Gandhāran Buddhist Texts, and concluded:

The view that Buddhism was transmitted to China by the sea route comparatively lacks convincing and supporting materials, and some arguments are not sufficiently rigorous [...] the most plausible theory is that Buddhism started from the Greater Yuezhi of northwest India and took the land roads to reach Han China. After entering into China, Buddhism blended with early Daoism and Chinese traditional esoteric arts and its iconography received blind worship.[39]

Origins of Buddhism

editFan Ye's Commentary noted that neither of the Former Han histories–the (109–91 BCE) Records or the Grand Historian (which records Zhang Qian visiting Central Asia) and (111 CE) Book of Han (compiled by Ban Yong)–described Buddhism originating in India:[34]

Zhang Qian noted only that: 'this country is hot and humid. The people ride elephants into battle.' Although Ban Yong explained that they revere the Buddha, and neither kill nor fight, he has recording nothing about the excellent texts, virtuous Law, and meritorious teachings and guidance. As for myself, here is what I have heard: This kingdom is even more flourishing than China. The seasons are in harmony. Saintly beings descend and congregate there. Great Worthies arise there. Strange and extraordinary marvels occur such that human reason is suspended. By examining and exposing the emotions, one can reach beyond the highest heavens.[40]

In the Book of Later Han, "The Kingdom of Tianzhu" (天竺, Northwest India) section of "The Chronicle of the Western Regions" summarizes the origins of Buddhism in China. After noting Tianzhu envoys coming by sea through Rinan (日南, Central Vietnam) and presenting tribute to Emperor He of Han (r. 89–105 CE) and Emperor Huan of Han (r. 147–167 CE), it summarizes the first "hard evidence" about Prince Ying and the "official" story about Emperor Ming:[41]

There is a current tradition that Emperor Ming dreamed that he saw a tall golden man the top of whose head was glowing. He questioned his group of advisors and one of them said: "In the West there is a god called Buddha. His body is sixteen chi high (3.7 metres or 12 feet), and is the colour of true gold." The Emperor, to discover the true doctrine, sent an envoy to Tianzhu (Northwestern India) to inquire about the Buddha's doctrine, after which paintings and statues [of the Buddha] appeared in the Middle Kingdom.

Then Ying, the king of Chu [a dependent kingdom which he ruled 41–71 CE], began to believe in this Practice, following which quite a few people in the Middle Kingdom began following this Path. Later on, Emperor Huan [147–167 CE] devoted himself to sacred things and often made sacrifices to the Buddha and Laozi. People gradually began to accept [Buddhism] and, later, they became numerous.[42]

Contacts with Yuezhi

editThere is a Chinese tradition that in 2 BCE, a Yuezhi envoy to the court of Emperor Ai of Han transmitted one or more Buddhist sutras to a Chinese scholar. The earliest version derives from the lost (mid-3rd century) Weilüe, quoted in Pei Songzhi's commentary to the (429 CE) Records of Three Kingdoms: "the student at the imperial academy Jing Lu 景盧 received from Yicun 伊存, the envoy of the king of the Great Yuezhi oral instruction in (a) Buddhist sutra(s)."[43]

Since Han histories do not mention Emperor Ai having contacts with the Yuezhi, scholars disagree whether this tradition "deserves serious consideration",[44] or can be "reliable material for historical research".[45]

The dream of Emperor Ming

editMany sources recount the "pious legend" of Emperor Ming dreaming about Buddha, sending envoys to Yuezhi (on a date variously given as 60, 61, 64 or 68 CE), and their return (3 or 11 years later) with sacred texts and the first Buddhist missionaries, Kāśyapa Mātanga (Shemoteng 攝摩騰 or Jiashemoteng 迦葉摩騰) and Dharmaratna (Zhu Falan 竺法蘭). They translated the "Sutra in Forty-two Sections" into Chinese, traditionally dated 67 CE but probably later than 100.[46] The emperor built the White Horse Temple (Baimasi 白馬寺) in their honor, the first Buddhist temple in China, and Chinese Buddhism began. All accounts of Emperor Ming's dream and Yuezhi embassy derive from the anonymous (middle 3rd-century) introduction to the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters.[47] For example, the (late 3rd to early 5th-century) Mouzi Lihuolun says,[48]

In olden days emperor Ming saw in a dream a god whose body had the brilliance of the sun and who flew before his palace; and he rejoiced exceedingly at this. The next day he asked his officials: "What god is this?" the scholar Fu Yi said: "Your subject has heard it said that in India there is somebody who has attained the Tao and who is called Buddha; he flies in the air, his body had the brilliance of the sun; this must be that god.[49]

Academics disagree over the historicity of Emperor Ming's dream but Tang Yongtong sees a possible nucleus of fact behind the tradition.[citation needed]

Emperor Wu and the Golden Man

editThe Book of Han records that in 121 BCE, Emperor Wu of Han sent general Huo Qubing to attack the Xiongnu. Huo defeated the people of prince Xiutu 休屠 (in modern-day Gansu) and "captured a golden (or gilded) man used by the King of Hsiu-t'u to worship Heaven."[50] Xiutu's son was taken prisoner, but eventually became a favorite retainer of Emperor Wu and was granted the name Jin Midi, with his surname Jin 金 "gold" supposedly referring to the "golden man."[51] The golden statue was later moved to the Yunyang 雲陽 Temple, near the royal summer palace Ganquan 甘泉 (modern Xianyang, Shaanxi).[52] The golden man has been demonstrated to be a three meters high colossal golden statue of Zeus holding a goddess by Lucas Christopoulos.[53]

The (c. 6th century) A New Account of the Tales of the World claims this golden man was more than ten feet high, and Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) sacrificed to it in the Ganquan 甘泉 palace, which "is how Buddhism gradually spread into (China)."[54][c]

Transmission to Korea

editCenturies after Buddhism originated in India, the Mahayana Buddhism arrived in China through the Silk Route in 1st century CE via Tibet, then to Korean peninsula in 3rd century during the Three Kingdoms period from where it transmitted to Japan.[56] The Samguk yusa and Samguk sagi record the following 3 monks who were among the first to bring Buddhist teaching, or Dharma, to Korea in the 4th century during the Three Kingdoms period: Malananta – an Indian Buddhist monk who came from either Serindian area of southern China's Eastern Jin dynasty or Gandhara region of northern Indian subcontinent and brought Buddhism to the King Chimnyu of Baekje in the southern Korean peninsula in 384 CE, Sundo – a monk from northern Chinese state Former Qin brought Buddhism to Goguryeo in northern Korea in 372 CE, and Ado – a monk who brought Buddhism to Silla in central Korea.[57][58] In Korea, it was adopted as the state religion of 3 constituent polities of the Three Kingdoms period, first by the Goguryeo (Gaya) in 372 CE, by the Silla in 528 CE, and by the Baekje in 552 CE.[56] As Buddhism was not seen to conflict with the local rites of nature worship, it was allowed by adherents of Shamanism to be blended into their religion. Thus, the mountains that were believed by shamanists to be the residence of spirits in pre-Buddhist times later became the sites of Buddhist temples.

Though it initially enjoyed wide acceptance, even being supported as the state ideology during the Goryeo (918–1392 CE) period, Buddhism in Korea suffered extreme repression during the Joseon (1392–1897 CE) era, which lasted over five hundred years. During this period, Neo-Confucianism overcame the prior dominance of Buddhism. Only after Buddhist monks helped repel the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) did the persecution of Buddhists stop. Buddhism in Korea remained subdued until the end of the Joseon period, when its position was strengthened somewhat by the colonial period, which lasted from 1910 to 1945. However, these Buddhist monks did not only put an end to Japanese rule in 1945, but they also asserted their specific and separate religious identity by reforming their traditions and practices. They laid the foundation for many Buddhist societies, and the younger generation of monks came up with the ideology of Mingung Pulgyo, or "Buddhism for the people." The importance of this ideology is that it was coined by the monks who focused on common men's daily issues.[59] After World War II, the Seon school of Korean Buddhism once again gained acceptance.

A 2005 government survey indicated that about a quarter of South Koreans identified as Buddhist.[60] However, the actual number of Buddhists in South Korea is ambiguous as there is no exact or exclusive criterion by which Buddhists can be identified, unlike the Christian population. With Buddhism's incorporation into traditional Korean culture, it is now considered a philosophy and cultural background rather than a formal religion. As a result, many people outside of the practicing population are deeply influenced by these traditions. Thus, when counting secular believers or those influenced by the faith while not following other religions, the number of Buddhists in South Korea is considered to be much larger.[61] Similarly, in officially atheist North Korea, while Buddhists officially account for 4.5% of the population, a much larger number (over 70%) of the population are influenced by Buddhist philosophies and customs.[62][63]

See also

edit- Pāli Canon & Early Buddhist texts

- Gandhāran Buddhist Texts

- Southern, Eastern and Northern Buddhism

- Sarvastivada

- Tamrashatiya

- Buddhism in China

- Buddhism in Southeast Asia

- Chinese Buddhism

- East Asian Buddhism

- Great Tang Records on the Western Regions

- Wang ocheonchukguk jeon

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

Notes

edit- ^ "In former times, the people of Fusang knew nothing of the Buddhist religion, but in the second year of Da Ming of the Song dynasty (485 CE), five monks from Kipin (Kabul region of Gandhara) traveled by ship to that country. They propagated Buddhist doctrine, circulated scriptures and drawings, and advised the people to relinquish worldly attachments. As a results the customs of Fusang changed." Ch: "其俗舊無佛法,宋大明二年,罽賓國嘗有比丘五人游行至其國,流通佛法,經像,教令出家,風 俗遂改.", Liang Shu "History of the Liang Dynasty, 7th century CE)

- ^ "These two Sanskrit terms, given in the Chinese text in phonetic transcription, refer to lay adepts and to Buddhist monks, respectively";[37] and show detailed knowledge of Buddhist terminology.

- ^ The (8th century) fresco discovered in the Mogao caves (near Dunhuang in the Tarim Basin) that depicts Emperor Wu worshipping two Buddhist statues, "identified as 'golden men' obtained in 120 BCE by a great Han general during his campaigns against the nomads". Although Emperor Wu did establish the Dunhuang commandery, "he never worshipped the Buddha."[55]

References

edit- ^ a b Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ^ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), pp. 22–27.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 30, for the Chinese text from the Hou Hanshu, and p. 31 for a translation of it.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), p. 23.

- ^ Samad, Rafi-us, The Grandeur of Gandhara. The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys, p. 234

- ^ a b c d e f Hahn, Thich Nhat (2015). The Heart of Buddha's Teachings. Harmony. pp. 13–16.

- ^ a b Oscar R. Gómez (2015). Antonio de Montserrat – Biography of the first Jesuit initiated in Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Editorial MenteClara. p. 32. ISBN 978-987-24510-4-2.

- ^ a b "History of Buddhism – Xuanfa Institute". Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- ^ Jacques, Martin. (2014). When china rules the world : the end of the western world and the birth of a new global order. Penguin Books. ISBN 9781101151457. OCLC 883334381.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 669–670.

- ^ Foltz, "Religions of the Silk Road", pp. 37–58

- ^ Tai Thu Nguyen (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. CRVP. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-56518-098-7. Archived from the original on 2015-01-31.

- ^ Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Soothill, William Edward; Hodous, Lewis (1995), A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms, London: RoutledgeCurzon https://web.archive.org/web/20140303182232/http://buddhistinformatics.ddbc.edu.tw/glossaries/files/soothill-hodous.ddbc.pdf

- ^ Chen, Jinhua (2004). "The Indian Buddhist Missionary Dharmakṣema (385–433): A New Dating of His Arrival in Guzang and of His Translations". T'oung Pao. 90 (4/5): 215–263. doi:10.1163/1568532043628340. JSTOR 4528970.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (2008). "Guṇabhadra, Bǎoyún, and the Saṃyuktāgama". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies: 185–203.

- ^ Joe Cribb, 1974, "Chinese lead ingots with barbarous Greek inscriptions in Coin Hoards" pp.76–8 [1]

- ^ Sundberg, J. "The Life of the Tang court monk Vjarabodhi as chronicled by Lü Xiang: South Indian and Sri Lankan antecedents to the arrival of Buddhist Vajrayana in 8th century Java and China": 64.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Taylor, Romeyn (May 1990). "Ancient India and Ancient China: Trade and Religious Exchanges, A.D. 1–600. By Xinru Liu. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988. xxii, 231 pp. $24.95". The Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (2): 360–361. doi:10.2307/2057311. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2057311. S2CID 128490585.

- ^ Ancient Silk Road Travellers

- ^ Jerry H. Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 43–44.

- ^ Jerry H. Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 48.

- ^ "Indian Gurus in Medieval China". Instagram. Connected Histories.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 9780230109100.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. Springer. p. 56. ISBN 9780230109100.

- ^ Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty. Harvard University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-674-05419-6.

- ^ Zürcher (2007), p. 20.

- ^ Saunders (1923), p. 158.

- ^ Draper (1995).

- ^ Williams (2005), p. 57.

- ^ a b Zürcher (1972), p. 26.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), p. 27. Compare Maspero (1981), p. 405.

- ^ Tr. by Zürcher (1972), p. 27.

- ^ Demiéville (1986), p. 821.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), p. 28.

- ^ Rong Xinjiang, 2004, Land Route or Sea Route? Commentary on the Study of the Paths of Transmission and Areas in which Buddhism Was Disseminated during the Han Period, tr. by Xiuqin Zhou, Sino-Platonic Papers 144, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Tr. by Hill (2009), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Zürcher (1990), p. 159.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 31. Compare the account in Yang Xuanzhi's (6th-century) Luoyang qielan ji 洛陽伽藍記, tr. by Ulrich Theobald.

- ^ Tr. by Zürcher (2007), p. 24.

- ^ Draft translation of the Weilüe by John E. Hill (2004) The Peoples of the West.

- ^ Zürcher (2007), p. 25.

- ^ Demieville (1986), p. 824.

- ^ Zürcher (2007), p. 22.

- ^ Zürcher (2007), p. 14.

- ^ Tr. by Henri Maspero, 1981, Taoism and Chinese Religion, tr. by Frank A. Kierman Jr., University of Massachusetts Press, p. 402.

- ^ Tr. Dubs (1937), 4–5.

- ^ Dubs (1937), 4–5.

- ^ Dubs (1937), 5–6.

- ^ Lucas Christopoulos; Dionysian rituals and the Golden Zeus of China. http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp326_dionysian_rituals_china.pdf pp.72–74

- ^ Zürcher (2007), p. 21.

- ^ Whitfield et al (2000), p. 19.

- ^ a b Lee Injae, Owen Miller, Park Jinhoon, Yi Hyun-Hae, 2014, Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press, pp. 44–49, 52–60.

- ^ "Malananta bring Buddhism to Baekje" in Samguk Yusa III, Ha & Mintz translation, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Kim, Won-yong (1960), "An Early Gilt-bronze Seated Buddha from Seoul", Artibus Asiae, 23 (1): 67–71, doi:10.2307/3248029, JSTOR 3248029, pg. 71

- ^ Woodhead, Linda; Partridge, Christopher; Kawanami, Hiroko; Cantwell, Cathy (2016). Religion in the Modern World- Traditions and Transformations (3rd ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-415-85881-6.

- ^ According to figures compiled by the South Korean National Statistical Office."인구,가구/시도별 종교인구/시도별 종교인구 (2005년 인구총조사)". NSO online KOSIS database. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ Kedar, Nath Tiwari (1997). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0293-4.

- ^ Religious Intelligence UK Report

- ^ [2] North Korea, about.com

Sources

edit- Demieville, Paul (1986). "Philosophy and Religion from Han to Sui", in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC. – AD. 220. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge University Press. Pp. 808–873.

- Draper, Gerald (1995). The contribution of the Emperor Asoka Maurya to the development of the humanitarian ideal in warfare. International Review of the Red Cross, No. 305.

- Dubs, Homer H. (1937). The "Golden Man" of Former Han Times. T'oung Pao 33.1: 1–14.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Michael C. Howard (23 February 2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Loewe, Michael (1986). "The Religious and Intellectual Background", in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC. – AD. 220, 649–725. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge University Press.

- Richard H. Robinson; Sandra Ann Wawrytko; Ṭhānissaro (Bhikkhu.) (1996). The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction. Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-534-20718-2.

774 787 srivijaya.

- Saunders, Kenneth J. (1923). "Buddhism in China: A Historical Sketch", The Journal of Religion, Vol. 3.2, pp. 157–169; Vol. 3.3, pp. 256–275.

- Tansen Sen (January 2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2593-5.

- Whitfield, Roderick, Whitfield, Susan, and Agnew, Neville (2000). Cave temples of Mogao: art and history on the silk road. Getty Publications.

- Williams, Paul (2005). Buddhism: Buddhist origins and the early history of Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis.

- Zürcher, Erik (2007). The Buddhist Conquest of China, 3rd ed. Leiden. E. J. Brill. 1st ed. 1959, 2nd ed. 1972.

- Zürcher, E. (1990). "Han Buddhism and the Western Region", in Thought and Law in Qin and Han China: Studies Dedicated to Anthony Hulsewe on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed by W.L. Idema and E. Zurcher, Brill, pp. 158–182.

Further reading

edit- Christoph Baumer, China's Holy Mountain: An Illustrated Journey into the Heart of Buddhism. I.B.Tauris, London 2011. ISBN 978-1-84885-700-1

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Sally Hovey Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang, Westview Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8133-6599-6

- JIBIN, JI BIN ROUTE AND CHINA