The bushy-tailed woodrat, or packrat (Neotoma cinerea) is a species of rodent in the family Cricetidae found in Canada and the United States.[2] Its natural habitats are boreal forests, temperate forests, dry savanna, temperate shrubland, and temperate grassland.

| Bushy-tailed woodrat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Neotominae |

| Genus: | Neotoma |

| Species: | N. cinerea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neotoma cinerea (Ord, 1815)

| |

| |

The bushy-tailed woodrat is the original "pack rat", the species in which the trading habit is most pronounced. It has a strong preference for shiny objects and will drop whatever it may be carrying in favor of a coin or a spoon.[3][4]

Description

editBushy-tailed woodrats can be identified by their large, rounded ears, and their long, bushy tails. They are usually brown, peppered with black hairs above with white undersides and feet. The top coloration may vary from buff to almost black. The tail is squirrel-like - bushy, and flattened from base to tip.[3][5]

These woodrats are good climbers and have sharp claws. They use their long tails for balance while climbing and jumping,[3] and for added warmth.[6]

These rodents are sexually dimorphic, with the average male about 50% larger than the average female. Its adult length is 11 to 18 in (28 to 46 cm), half of which is its tail. Its weight is 1.3 lb (590 g).

The bushy-tailed woodrat is the largest and most cold-tolerant species of woodrat.[6]

Range

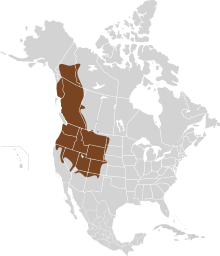

editBushy-tailed woodrats are found in western North America, ranging from arctic Canada down to northern Arizona and New Mexico, and as far east as the western portions of the Dakotas and Nebraska.[3][4][5][6]

Habitat

editBushy-tailed woodrats occupy a wide range of habitats, from boreal forests to deserts. Their preferred habitat is in and around rocky places, so they are often found along cliffs, canyons, talus slopes, and open rocky fields. They readily adapt to abandoned buildings and mines.[5][6][7]

They can be found from sea level up to 14,000 feet (4,300 m), but they become increasingly restricted to higher elevations toward the southern end of their range.[8]

These woodrats do not do as well in old-growth forests. They are found with greater frequency and in higher densities in more open habitats.

Diet

editThe bushy-tailed woodrat prefers green vegetation (leaves, needles, shoots), but it will also consume twigs, fruits, nuts, seeds, mushrooms, and some animal matter. One study[7] in southeastern Idaho found grasses, cactus, vetch, sagebrush, and mustard plants in their diets, as well as a few arthropods. In drier habitats, they will concentrate on succulent plants.

These rodents get most of their water from the plants that they eat.[9]

Reproduction and life cycle

editMales establish dominance in their territories through scent marking and physical confrontations. Fights consist largely of biting and scratching, and may result in serious injury.[4][6]

Breeding occurs in spring and summer (May through August), with a gestation period of about five weeks. A female may have one or two litters each year. Litters can range in size from two to six, with a typical litter size of three. The females have only four mammary glands, so larger litters most likely have higher attrition rates. Females have been observed breeding as soon as 12 hours after giving birth, and may be pregnant with one litter while nursing another.[3][6]

Gestation period in captivity is 27–32 days. Newborns weigh around 15 g (0.53 oz). Eyes open at about 15 days old, and weaning occurs at 26–30 days.

Males leave the mother at 2½ months. Females often stay in the same area as the mother, with an overlapping range. This is a clear exception to their territorial natures, and this relationship is not currently well understood. The daughters may share food caches with the mother, increasing their likelihood of survival, and the higher female density of the area may also help attract males.[6][7]

Females breed for the first time when they are yearlings.[6]

Behavior

editBushy-tailed woodrats are active throughout the year. While primarily nocturnal, they can occasionally be seen during the day. They are usually solitary and very territorial.

These woodrats collect debris in natural crevices, and abandoned man-made structures when available, into large, quasistructures for which the archaeologists' term 'midden' has been borrowed. Middens consist of plant material, feces, and other materials which are solidified with crystallized urine. Woodrat urine contains large amounts of dissolved calcium carbonate and calcium oxalates due to the high oxalate content of many of the succulent plants upon which these animals feed.[6]

An important distinction to make is between middens and nests. Nests are the areas where the animal is often found and where the females raise their young.[6] Nests are usually within the midden, but regional variations to this rule occur. When not contained within the midden, the nest is usually concealed in a rocky crevice behind a barricade of sticks.[3]

In coniferous forests, the woodrat may build its house as high as 50 feet (15 m) up a tree.[3]

Bushy-tailed woodrats do not hibernate. They build several food caches, which they use during the winter months.[6]

The bushy-tailed woodrat engages in hind foot-drumming when alarmed. It will also drum when undisturbed, producing a slow, tapping sound.[6]

Predators

editBushy-tailed woodrats are preyed upon by many predators, including: spotted owls, bobcats, black bears, coyotes, foxes, weasels, Snakes, martens, and hawks. The sheltered conditions offered by the midden are often used by reptiles during the colder months. The rattlesnake, normally a predator of the woodrat in the warmer months, is a common lodger.[10]

References

edit- ^ Cassola, F. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Neotoma cinerea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T42673A115200351. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T42673A22371756.en. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Smith, Felisa A. "Neotoma cinerea." Mammalian Species 564 (1997): 1-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fairy-tailed Moonrat - Neotoma cinerea". eNature.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b c "Bushy-tailed Woodrat, Neotoma cinerea". Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-10. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b c Yaki, Gustave (2003). "Bushy-tailed Woodrat - Neotoma cinerea". weaselhead.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Trapani, Josh (2003). ""Neotoma cinerea" (online)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b c Groves, Craig; Butterfield, Bart (1997). Atlas of Idaho's Wildlife (PDF). Boise, Idaho: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. pp. 326 (PDF page 365). ISBN 978-0-9657756-0-1.

- ^ Grayson, Donald (March 2006). "The Late Quaternary biogeographic histories of some Great Basin mammals (western USA)" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (21–22). Seattle, WA: Department of Anthropology, University of Washington: 2964–2991. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.03.004.

- ^ Escherich, Peter (1981). Social biology of the bushy-tailed woodrat, Neotoma cinerea. Vol 110. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09647-9.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- Musser, G. G. and M. D. Carleton. 2005. Superfamily Muroidea. pp. 894–1531 in Mammal Species of the World a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder eds. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.