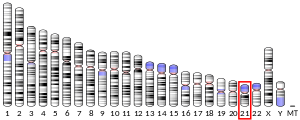

Exosomal polycystin-1-interacting protein is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the EPCIP gene.[6] EPCIP is found on human chromosome 21, and it is thought to be expressed in tissues of the brain and reproductive organs.[7] Additionally, EPCIP is highly expressed in ovarian surface epithelial cells during normal regulation, but is not expressed in cancerous ovarian surface epithelial cells.[7]

| EPCIP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | EPCIP, B37, C21orf120, PRED81, chromosome 21 open reading frame 62, C21orf62 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 1921637; HomoloGene: 49594; GeneCards: EPCIP; OMA:EPCIP - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gene

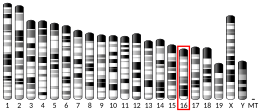

editCommon aliases of EPCIP are C21orf62, C21orf120, PRED81, and B37.[6] EPCIP is located on chromosome 21 in humans, and is specifically at the q22.11 position.[8] The EPCIP gene is 4132 base pairs in length and contains five exons.[6]

mRNA

editThe mRNA sequence of EPCIP in humans has one known isoform. This isoform is called uncharacterized protein C21orf62 isoform X1. This isoform is 458 base pairs, or 104 amino acids, in length, and it is significantly shorter than the most observed sequence of EPCIP in humans. In addition to having an isoform, EPCIP also has splice variants. All splice variants encode the same gene, but the differences in splice variant sequences occur in the 5' untranslated region of the mRNA sequence.[6]

Protein

editGeneral protein characteristics

editThe EPCIP protein in humans has a sequence that is 219 amino acids in length.[9] The primary sequence of EPCIP in humans has a molecular weight of 24.9 kDa and an isoelectric point of 8.[10][11] When it's cleavable signal peptide, which spans amino acids 1-19, is removed, it has a molecular weight of 22.8 kDa and an isoelectric point of 7.8.[10][11][12][13]

Protein composition

editEPCIP in humans has higher cysteine and lower valine concentrations than expected compared to other human proteins. This trend, as showed in Table 1, is the same for other mammals. It does not, however, occur in taxa other than mammalia.[14]

| Genus and Species | Common Name | Organism Clade | % Cysteine | Amino Acid Concentration of Cysteine Compared to Expected | % Valine | Amino Acid Concentration of Valine Compared to Expected | Other Amino Acids with High or Low Concentration Compared to Expected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Human | Mammalia | 4.6% | High | 3.2% | Low | - |

| Mus musculus | House Mouse | Mammalia | 4.3% | High | 3.5% | Low | Glutamic Acid (1.7%, low) |

| Canis lupus familiaris | Dog | Mammalia | 4.1% | High | 2.7% | Low | Leucine (14.2%, high) |

| Physeter catodon | Sperm Whale | Mammalia | 4.6% | High | 4.1% | Expected | Serine (11.9%, high) |

| Gallus gallus | Chicken | Aves | 3.1% | Expected | 6.7% | Expected | Alanine (2.2%, low)

Glycine (3.1%, low) Proline (1.8%, low) Phenylalanine (7.1%, high) Serine (12.4%, high) Threonine (9.8%) |

| Chelonia mydas | Green Sea Turtle | Reptilia | 3.6% | Expected | 5.8% | Expected | Alanine (1.8%, low)

Serine (11.2%, high) |

Protein structure

editThe protein structure of EPCIP in humans consists of a combination of alpha helices and beta sheets.[15][16] Figure 1 shows a predicted structure of the protein.[5]

Post-translational modifications

editEPCIP has a myristoylation site from amino acid 26–31.[17] It has a sumoylation site from amino acid 132–135.[17][18] Additionally, it has a nuclear export signal from amino acid 98-104.[19]

Expression

editTissue expression

editEPCIP is expressed in human tissues of the brain and reproductive organs.[6]

Expression level

editEPCIP in humans is moderately expressed in the brain, kidneys, pancreas, prostate, testes, and ovaries.[6][20][21]

Regulation of expression

editEPCIP is expressed during blastocyst, fetus, and adult states of human development.[20] It is overexpressed during some tumor states, including pancreatic, gastrointestinal, germ cell, and glioma tumors.[20]

Function

editThe specific function of EPCIP in humans is not yet well understood.[6]

Interacting proteins

editEPCIP is thought to potentially interact with nine other proteins.[22] These interactions are shown in Table 2, and they were found through text mining.

| Protein Full Name | Protein Name Symbol | Brief Protein Description[6] |

|---|---|---|

| BCL2 Interacting Protein Like | BNIPL | May function as a bridge molecule that promotes cell death. |

| Thymosin Beta 4, X-linked Pseudogene 4 | TMSB4XP4 | Potentially influences actin polymerization. |

| Synovial Sarcoma X Family Member 4 | SSX4 | May function as a repressor of transcription, and can be useful targets in cancer vaccine-based immunotherapy. |

| Crystallin Beta A2 | CRYBA2 | A major protein in vertebrate eyes that maintains lens transparency and reflective index. |

| Oral Cancer Overexpressed 1 | ORAOV1 | A gene that is frequently overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell cancer. |

| Oligodendrocyte Transcription Factor 1 | OLIG1 | May be expressed during the time from process extension through membrane maintenance in oligodendrocytes. |

| PAX3 and PAX7 Binding Protein 1 | GCFC1 (PAXBP1) | The encoded protein potentially binds to GC-rich DNA sequences. It is suggested that this gene is involved in the regulation of transcription. |

| Relaxin/Insulin Like Family Peptide Receptor 1 and 2 | RXFP1 and RXFP2 | Encoded protein is a receptor for the protein hormone relaxin that influences sperm motility and pregnancy. |

Clinical significance

editEPCIP over or under expression is linked to some types of cancerous cells and tumors.[7][20]

Homology

editParalogs

editThere are no known paralogs of EPCIP in humans at this time.[6]

Orthologs

editThere are currently 193 organisms that are known to be orthologs of EPCIP.[6] The orthologs of EPCIP are deuterostome animals in the clade Chordata.[6] Table 3 shows a range of EPCIP orthologs, their NCBI accession numbers, sequence lengths, and sequence identity to the EPCIP human protein. At this time, EPCIP is not known to have any protostome or invertebrate orthologs.[6]

| Genus and Species | Common Name | Organism Clade | Estimated Date of Divergence from Humans (Millions of Years Ago)[23] | Accession Number[9] | Amino Acid Sequence Length[9] | Corrected Sequence Identity to Human Protein[24][25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Human | mammalia | 0 | NP_001155967.2 | 219 | 100% |

| Mus musculus | House Mouse | mammalia | 90 | NP_083181.1 | 230 | 68.2% |

| Meleagris gallopavo | Wild Turkey | aves | 312 | XP_010721230.1 | 225 | 56.4% |

| Chelonia mydas | Green Sea Turtle | reptilia | 312 | XP_007063646.1 | 224 | 60.8% |

| Xenopus tropicalis | Western Clawed Frog | tetrapoda | 352 | NP_001004889.1 | 207 | 48.9% |

| Latimeria chalumnae | West Indian Ocean Coelacanth | sarcopterygii | 413 | XP_005993681.2 | 237 | 45.0% |

| Ictalurus punctatus | Channel Catfish | actinopterygii | 435 | XP_017326002.1 | 214 | 29.6% |

| Callorhinchus milii | Australian Ghostshark | condrichthyes | 473 | XP_007904174.1 | 222 | 40.4% |

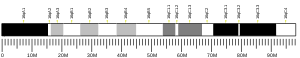

Evolution rate

editEPCIP has an evolution rate that is faster than cytochrome C and fibrinogen. Figure 2 shows the rate of evolution of the EPCIP gene over the past 473 million years.

External links

edit- Human C21orf62 genome location and C21orf62 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

References

edit- ^ a b c ENSG00000205929 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000262938, ENSG00000205929 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000039851 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Kelley L. "PHYRE2 Protein Fold Recognition Server". www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "EPCIP exosomal polycystin 1 interacting protein [ Homo sapiens (human) ]". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ a b c "Home - GEO Profiles - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Database GH. "C21orf62 Gene - GeneCards | CU062 Protein | CU062 Antibody". www.genecards.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b c d "Protein". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b Kramer J (1990). "AASTATS". Biology Workbench.

- ^ a b Toldo L. "PI Isoelectric Point Determination Program". Biology Workbench.

- ^ "PSORT II server - GenScript". www.genscript.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Charpilloz JL. "TERMINUS - Welcome to terminus". terminus.unige.ch. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b Brendel V (1992). "Statistical Analysis of PS". Biology Workbench. Archived from the original on 2003-08-11. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ Pearson WR (September 1998). "CHOFAS Analysis". Biology Workbench. Archived from the original on 2003-08-11. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ Pappas GJ Jr (1974–1996). "PELE: Protein Structure Prediction". Biology Workbench. Archived from the original on 2003-08-11. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ a b "Motif Scan". myhits.isb-sib.ch. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ The Cucko Workgroup (May 1, 2017). "GPS-SUMO 2.0 Online Service". sumosp.biocuckoo.org/online.php. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ la Cour T, Kiemer L, Mølgaard A, Gupta R, Skriver K, Brunak S (2004). "Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals". Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17 (6): 527–36. doi:10.1093/protein/gzh062. PMID 15314210.

- ^ a b c d "Home - UniGene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ "The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b "STRING: functional protein association networks". string-db.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ "TimeTree :: The Timescale of Life". timetree.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ "BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool". blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Myers EW, Miller W (March 1988). "Optimal alignments in linear space". Computer Applications in the Biosciences. 4 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.11. S2CID 8140207.