The Cambrian quarry was a slate quarry, located to the west of Glyn Ceiriog in Denbighshire, North Wales. There was some small-scale extraction of slate from the 17th century, but commercial extraction began in 1857, and the scale of operation increased from 1873, when the Glyn Valley Tramway opened, providing an easier route to market for the output of the quarry. Production after 1938 was on a reduced scale, and the quarry closed in the winter of 1946/47, mainly due to a lack of workers.

One of the chambers within Martin's quarry, at the western end of Cambrian quarry | |

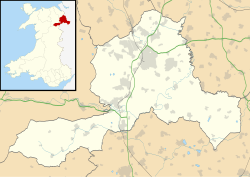

| Location | |

|---|---|

Location in Wrexham County Borough | |

| Location | near Glyn Ceiriog |

| County | Wrexham County Borough |

| Country | Wales |

| Coordinates | 52°56′N 3°13′W / 52.93°N 3.21°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Slate |

| Type | Quarry |

History

editExtraction of slate from the site to the west of Glyn Ceiriog is thought to have begun in the 17th century,[1] but was certainly established by the late 18th century at Chwarel Isaf (Lower Quarry), where William Davies died in 1770 as a result of a rock fall. David Davies is known to have quarried there between 1772 and 1792, and when Chwarel Isaf farm was auctioned in 1799, the sale document noted that it contained two capital and inexhaustible slate quarries on the lands, now in full work. William Hazeldine, an iron master from Shrewsbury, bought the quarry in 1818, and ran it in partnership with William Edwards, under the name Hazeldine & Edwards. Chwarel Isaf was later known as McEwen's quarry.[2]

In 1857, the Cambrian Slate Company Ltd was formed to extract Ceiriog slate commercially. The company estimated that they would be producing 4,000 tons of slate per year, and spent £22,000 building tramways, an incline, a water engine, a weighing machine and various buildings.[3] Operation began in 1857 at Chwarel Isaf, and at Chwarel Uchaf (Upper quarry), a little further to the west, in the 1860s. This became known as Martin's quarry, and was equipped with a mill powered by a water wheel. It became a pit as the depth of the excavation increased, and to resolve issues of drainage and removal of the slate, a tunnel was bored from the bottom of the pit, running for some 600 yards (550 m) eastwards, to emerge beyond Chwarel Isaf. Two shafts were subsequently constructed from the surface down to the tunnel, and these later developed into Townsend's and Dennis's quarries. There was a slump in the slate industry in the 1870s, when work ceased, but extraction restarted in the 1880s, when Townsend's quarry was worked downwards, to reach the tunnel, and a branch tunnel was constructed below McEwen's quarry, again to provide drainage and a route out for the slate and waste.[4]

Transportation was an issue, as the nearest turnpike road had been built in 1771 from Wem in Shropshire to Bronygarth, where there was a limestone quarry and kilns. Bronygarth was further down the Ceiriog valley, some 1.75 miles (2.82 km) west of Chirk, but the turnpike trustees did not have sufficient funds to extend the road to Glyn Ceiriog. The Cambrian Slate Company reached an agreement with the trustees that they would fund the extension of the road, and could build a tramway beside both the new and the existing road as far as Preesgwyn station on the railway from Shrewsbury to Chester. They prepared a bill to submit to Parliament, to authorise a private-carrier tramway, on the understanding that if there was opposition to the proposal, they would withdraw the bill. It was opposed by the owner of Chirk Castle, Colonel Biddulph, who wanted it to be a public carrier, and so the bill was withdrawn. The turnpike trustees then produced their own bill, which included a clause to allow the Cambrian Slate Company to construct a tramway beside their road. The House of Commons Select Committee rejected the clause, as "they had never before been asked to unite railroads and turnpike roads together and did not consider it their duty to do so now for the first time." Although the Act of Parliament did not therefore mention the tramway, the Cambrian Slate Company paid half the cost of a road from Chirk to Glyn Ceiriog, and received the tolls from the new section, which was built sufficiently wide that a tramway could be built in due course.[5] Following the passing of the Tramways Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 78), a new bill for a tramway beside the road was introduced, and on 10 August 1870, the Glyn Valley Tramway was authorised. The Cambrian Slate Company were not involved in the promotion of the horse-drawn tramway, but one of the most costly parts of its construction was the gravity incline from the Cambrian quarry down to Glyn Ceiriog, some 0.5 miles (0.8 km) of double track at an average gradient of 1 in 8, which cost £2,237 to build.[6]

Dennis's pit was shallower than the others, and although it was drained through the main tunnel, two tunnels at a higher level were constructed to extract the rock. Both headed southwards, and the first was short-lived, but the second, at a deeper level, was linked to the mill near the exit of the main tunnel. Underground mining of the slate began when chambers were excavated close to the main tunnel near Townsend's quarry. New working to the west of Martin's quarry were mined by extending the tunnel beyond the open working. Underground chambers were eventually created on four levels. Although waste rock was initially removed through the tunnel and dumped to the east of the workings, this became more difficult due to lack of space, so inclines were built in Townsend's and Martin's quarries to allow the waste to be dumped further west. There was also an incline in the western workings.[4] Dennis's quarry was abandoned some time around 1900, and the tunnel which connected it to the main access tunnel was plugged with concrete. The quarry flooded, and a valve controlled the flow of water through the concrete plug, which then drove a turbine to power the dressing mill. The quarry became known as Quarry Pool, although there were actually two pools, separated by a causeway.[7]

Mechanisation

editIn March 1896, the Cambrian quarry announced in a journal that they would be replacing the horses which were used to pull wagons on the internal railway system with locomotives. However, horses continued in use until 1910, when they took delivery of a diminutive 'Ferret' class locomotive from W G Bagnall of Stafford. It was an 0-4-0 saddle tank with outside cylinders, and was oil fired. The gauge of the internal tracks at the quarry was 2 ft (610 mm), although the gauge specified for the locomotive was 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in).[8] The locomotive was just 5 feet (1.5 m) high and 4 feet 2 inches (1.27 m) wide, as it had to run through the main tunnel, which was around 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) high. The cab floor was only just above the rails, and the driver was required to sit astride the rear buffer beam.[9] One advantage of the oil-firing system was that the burners could be turned off while the locomotive ran through the tunnels, and turned back on when it was in the open air to raise steam.[8] It was probably converted to coal firing at some point, since Captain T P Crossland, in a lecture to the Institute of Quarrying given in 1932, stated that the fumes were fierce, standby costs were heavy, and the company had experienced difficulties obtaining best quality steam coal for it.[10]

The steam locomotive was replaced by a Motor Rail 'Simplex' machine in 1921. It was a 20 hp (15 kW) bow-frame model, weighing 2.5 tons, and fitted with a Dorman twin-cylinder petrol engine. The steam locomotive was sold on, and saw further service at the Carrington Road Brickworks, near Davyhulme, Greater Manchester.[11] By 1930, the cylinders of the Simplex required reboring, and the company bought a new engine, exchanged it over a weekend, and then sent the old one away to be rebored.[12] A second petrol locomotive was obtained in 1929 from F C Hibberd, as the Simplex was too wide to work the Aberlas workings at the western end of the quarry. It was a 10 hp (7.5 kW) 'Planet' machine with a 4-cylinder Meadows engine and weighed 1.75 tons. After closure of the quarry, the Simplex was sold to the Penmachno Slate Quarry near Betws-y-Coed, where it lasted until 1964, but there is no record of the Planet being sold, and it was probably scrapped on site.[13]

Apart from the closure in the 1870s, the quarries were worked consistently, employing up to 90 men, and producing around 2000 tons of finished product per year. Roofing slates continued to be made until the 1930s, and the quarry remained open until 1946.[4] When the Glyn Valley Tramway closed in 1936, the company bought the incline and 16 wagons, to enable them to move slates from the mill to Glyn Ceiriog.[14] During the Second World War, the quarry was, like most businesses, required to pay for special insurance against war damage, and two locomotives were listed in their assets. In case there was an invasion, many quarries were used to store essential supplies, and the Cambrian quarry was used by the Automatic Telephone Company to store telephony equipment, which was not removed until 1946.[15] By 1946, the quarry was in financial difficulties, which was worsened by wage increases and a cap on how much prices for the slates could be increased. The winter of 1946 was particularly severe, and the quarry closed because of bad weather in March 1947. Several of the men were employed by the council to remove snow, and when the quarry attempted to reopen, they declined to return to work, resulting in the quarry officially closing on 15 March.[16] This was a particular blow to Alan Taylor, the company chairman, who had been propping up the quarry with his own money for some years, in order to ensure there was work for the residents of Glyn Ceiriog. Three men were retained to salvage equipment from the chambers, and a fourth carried on producing slates from available blocks, in order to cover the wages of the men. However, the pumps failed, and chambers below the level of the main tunnel soon became flooded, preventing any further salvage work.[17]

A closing auction took place on 14 July 1948, and during the winding up procedure the accountants found that Taylor had invested some £10,000 of his own money to keep the quarry solvent. Most of the winding drums from the inclines were bought by the Pen-y-Graig limestone quarry at Froncysyllte, where they were reused.[18] Following closure, Quarry Pool was stocked with trout, and became a popular location for fishing. A routine inspection in 1975 by the Forestry Commission, who owned the site, found that a landslide had partially blocked the main tunnel, resulting in further flooding. Quarry Pool was drained in 1978 as a precaution against flooding in the village, by releasing its water through the valve in the tunnel, despite the protests of Miss Elizabeth Taylor, who owned the fishing rights and who had stocked the pool with trout.[19]

Geology

editThe Ceiriog Valley is some 17 miles (27 km) long, and is composed of many types of rock, including china stone, coal deposits, granite, limestone, silica, slate, and volcanic ash. In the lower valley, smelting of iron and coal mining began in the early 1600s. The slate beds on the north and north-western side of the valley date from the Silurian period, and are known as the 'Wenlock' beds. The same rock has also been quarried near Llangollen, Horseshoe Pass, Corwen and Llangynog. Slate found on the south and south-western side of the valley is from the older Ordovician period, which is also found in the Ffestiniog area, while the Penrhyn quarry, Dinorwic quarry and quarries in the Nantlle area extracted slate from the even older Cambrian era.[20]

Ceiriog slate was comparatively soft, and was more difficult to split into thin, uniform roofing slates, resulting in them being less valuable than those from other areas. Much of the slate also included deposits of iron disulphide, a shiny yellow mineral which weathered rapidly, as well as cephalopods and other marine fossils from the Palaeozoic era. Walter Davies, writing in 1810, noted that when exposed to sulphuric acid, slates from Glyn Ceiriog took only four days to decompose and were less durable than slates from other regions. This is most notable on the waste tips in the valley, which, some 60 years after the quarries closed, support trees and vegetation, because the rock has broken down to become like mulch, and even rabbits can burrow into the tips. This is in contrast to the quarry at Ty Draw, on the southern side of the valley, where the harder Ordovician slate has prevented much vegetation from growing.[21]

Through the Cambrian quarries, the slate beds dipped down at around 15 degrees, with the cleavage plane sloping at 25 degrees. Because the slate appeared as outcrops, it was initially worked as open quarries, pits or galleries, but as the slate vein dipped downwards, underground chambers were mined when the cost of removing the overlying rock became too great.[21] While the slate beds at the nearby Wynne quarry were all given names, and there were many of them, no name appears on any official documents for the vein that ran through the Cambrian quarries.[22]

Bibliography

edit- Davies, David Llewwellyn (1966). The Glyn Valley Tramway. Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-1-900622-11-0.

- Milner, John (2008). Slates from Glyn Ceiriog. Ceiriog Press. ISBN 978-1-900622-11-0.

- Richards, Alun John (1991). A Gazeteer of the Welsh Slate Industry. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 978-0-86381-196-8.

- Richards, Alun John (1999). The Slate Regions of North and Mid Wales. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 978-0-86381-552-2.

References

edit- ^ Richards 1991, p. 196.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Davies 1966, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Richards 1999, p. 237.

- ^ Davies 1966, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Davies 1966, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 118.

- ^ a b Milner 2008, p. 157.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 158.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 165.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 147.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Milner 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Milner 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Milner 2008, pp. 20–21.

External links

editMedia related to Cambrian quarry at Wikimedia Commons