This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (August 2024) |

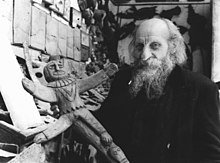

Carlo Crespi Croci (29 May 1891 – 30 April 1982) was an Italian Salesian priest, anthropologist, and filmmaker. He lived for over sixty years as a missionary in Ecuador.

Carlo Crespi Croci | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 May 1891 |

| Died | 30 April 1982 (aged 90) |

| Resting place | Cementerio Patrimonial de Cuenca |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Occupation(s) | Catholic priest, missionary, anthropologist, filmmaker |

Biography

editCarlo Crespi was the third of thirteen children born to Daniele Crespi, a peasant, and his wife Luisa Croci. In 1907, he began his novitiate in Foglizzo and between 1909 and 1911 he studied philosophy in Valsalice, where he met priest Renato Ziggiotti, who would live to become the successor of John Bosco. On Sunday, 28 January 1917, Crespi was ordained priest.[1][2]

In 1921, Crespi graduated in natural sciences, specializing in botany, at the University of Padua. He defended a thesis entitled "Contribution to the knowledge of fresh water fauna in the region of Este and neighboring locations. Swamps, channels, pits, sources of Euganei, of lakes from Arquà and Venda." Three months later, he graduated in piano and composition in the Cesare Pollini conservatory, located in the same city.

During his time in Ecuador, he lived with the Shuar people of the Amazon. In addition to his religious work, he dedicated himself to education, cinema, anthropology, and archaeology. He was one of the first to investigate the Cueva de los Tayos.[3] He was one of the forerunners of Ecuadorian cinema with his documentary The invincible Shuaras of High Amazonas (1926). Its images were recovered and stored years after the footage was taken.[4][5][6]

During his missionary life, he collected a number of archaeological artifacts, with which he intended to form a museum. After some thefts, in 1978, with his assent, it was decided that works with a certain value would be bought because of a debt with the Central Bank of Ecuador. Over five thousand objects with archaeological value and character were inventoried and sold, as well as a smaller number of objects of sculptural or ethnographic aspect. Some of them were out-of-place artifacts that some assumed to have been created before the Great Flood, around which interest and debate already had developed.[7][8][9] When interviewed, Crespi always declared that all elements in his museum were donated to him by the Shuar, who in turn took them from the Cueva de los Tayos.[10]

He was mainly active in Cuenca, where he founded numerous schools and educational institutes, as well as eateries and laboratories dedicated to poor children. In 1940, he founded the Faculty of Education and was its first dean. He was proclaimed "Cuenca's most illustrious citizen in the 20th century". His memory was immortalized in the names of several institutions and places such as a street and a square where a statue representing him with a child stands.[11][12]

References

edit- ^ "Don Carlo e Legnano". Associazione Padre Carlo Crespi ONLUS (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Don Carlo Sacerdote (Parte Prima)". Associazione Padre Carlo Crespi ONLUS (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "La Cueva de los Tayos debe declararse patrimonio" (in Spanish). El Telégrafo. 24 January 2017.

- ^ Jorge Luis Serrano (9 May 2014). "El pionero". El Tiempo. Diario de Cuenca (in Spanish).

- ^ "Don Carlo Pioniere della Cinematografia Ecuadoriana". Associazione Padre Carlo Crespi ONLUS (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Historia del cine ecuatoriano: Parte 3". El ojo en el fotograma (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Don Carlo e il suo Museo (da "Siervo de Dios P. Carlos Crespi Croci …") – Parte prima". Associazione Padre Carlo Crespi ONLUS (in Italian). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Don Carlo e il suo Museo (da "Siervo de Dios P. Carlos Crespi Croci …") – Parte Seconda". Associazione Padre Carlo Crespi ONLUS (in Italian). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Isabel Aguilar (6 December 2018). "Colección Crespi, entre la reserva y el patrimonio" (in Spanish). El Tiempo. Diario de Cuenca.[dead link]

- ^ "The mystery of Father Carlo Crespi's metal library • Neperos". Neperos.com.

- ^ "Carlo Crespi. Vero genio, vero santo". Il Bollettino Salesiano (in Italian). 2020 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Homenaje a Carlos Crespi Croci en su onomástico" (in Spanish). Diario El Mercurio. 1 November 2019.

En el parque María Auxiliadora se erige un monumento a la labor social y pastoral de Carlos Crespi.

[dead link]