In Greek mythology, Cepheus (/ˈsiːfiəs, -fjuːs/; Ancient Greek: Κηφεύς Kepheús) was the name of two rulers of Aethiopia, grandfather and grandson.

| Cepheus | |

|---|---|

King of Aethiopia | |

| |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | |

| Parents | Belus and Achiroe |

| Siblings | Danaus, Aegyptus, Phineus |

| Consort | Cassiopeia |

| Offspring | Andromeda |

Family

editCepheus was the son of either Belus,[1] Agenor[2] or Phoenix.[3] If Belus was his father, he had Achiroe, daughter of Nilus, as his mother, and Danaus, Aegyptus, and Phineus as brothers. He was called Iasid Cepheus, pertaining to his Argive ancestry through King Iasus of Argus, father of Io.[4]

Mythology

editCepheus is prominently featured in the Perseus legend as the husband of Cassiopeia, father of Princess Andromeda, and brother of Phineus, who expects to marry Andromeda. Various sources describe his kingdom to be "Aethiopia" or later, the city of Joppa (Jaffa) in Phoenicia, which was named after the elder Cepheus's wife, Iope, daughter of Aeolus.[5]

Cassiopeia boasts that Andromeda is more beautiful than the Nereids, angering both the sea nymphs and Poseidon. In response, Poseidon sends a flood and the sea monster Cetus to attack Aethiopia. Cepheus and Cassiopeia seek guidance from the oracle of Ammon (identified with Zeus) at the oasis of Siwa in the Libyan desert; she declares the calamity will not end until Andromeda is offered to the monster as a human sacrifice. The king chains his daughter to a rock by the shore to be devoured by Cetus at the whim of his subjects.

Andromeda is saved when Perseus, flying home with his trophy head of Medusa, passes by the kingdom of Cepheus and notices a beautiful girl chained to a rock on the shore. Perseus falls in love with her and undertakes to slay the monster if she promises to marry him; in a slightly different version, he approaches Cepheus. The hero then kills the monster (or turns it to stone by showing it the Gorgon’s head). Perseus washes off his blood in a spring near the city of Joppa, which apocryphally turns red as a result.[6]

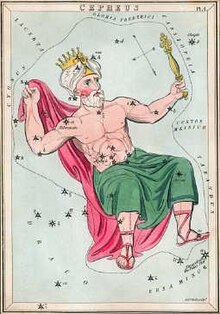

Cepheus and Cassiopeia allow Perseus to become Andromeda's husband after he uses Medusa's head to turn Phineus and his men to stone for plotting against him.[7] According to Hyginus, the betrothed of Andromeda is named Agenor.[8] After spending a year or so at the court of his father-in-law, Perseus finally sets off for Seriphos with his wife. Since Cepheus has no heir of his own, the departing couple allows him to adopt their first-born child, Perses, who is destined to give his name to the Persians. Cepheus is later made into the constellation Cepheus.

Notes

edit- ^ Herodotus, 7.61; Apollodorus, 2.1.4

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.682–683

- ^ Hyginus, De astronomica 2.9.1

- ^ Aratus, Phaenomena 189

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Iope: Ἰόπη

- ^ Pausanias, 4.35.9

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.1–238

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 64

References

editPrimary sources

edit- Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Aratus Solensis, Phaenomena translated by G. R. Mair. Loeb Classical Library Volume 129. London: William Heinemann, 1921. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Aratus Solensis, Phaenomena. G. R. Mair. London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1921. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Astronomica from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Hyginus. Fabulae and Astronomica. Translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies, no. 34. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Herodotus, The Histories with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. ISBN 0-674-99133-8. Online version at the Topos Text Project. Greek text available at Perseus Digital Library.

- Nonnus of Panopolis, Dionysiaca translated by William Henry Denham Rouse (1863-1950), from the Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1940. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Nonnus of Panopolis, Dionysiaca. 3 Vols. W.H.D. Rouse. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1940-1942. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. ISBN 0-674-99328-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses translated by Brookes More (1859-1942). Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Stephani Byzantii Ethnicorum quae supersunt, edited by August Meineike (1790-1870), published 1849. A few entries from this important ancient handbook of place names have been translated by Brady Kiesling. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

Secondary sources

edit- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- The Heroes Or, Greek Fairy Tales for my Children by Charles Kingsley (1901). Page 38