The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), officially the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, is an arms control treaty administered by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), an intergovernmental organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands. The treaty entered into force on 29 April 1997. It prohibits the use of chemical weapons, and also prohibits large-scale development, production, stockpiling, or transfer of chemical weapons or their precursors, except for very limited purposes (research, medical, pharmaceutical or protective). The main obligation of member states under the convention is to effect this prohibition, as well as the destruction of all current chemical weapons. All destruction activities must take place under OPCW verification.

| Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

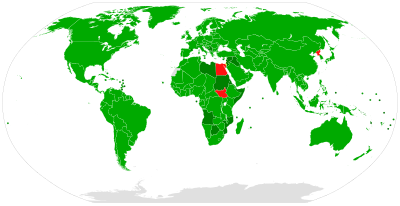

Participation in the Chemical Weapons Convention

| |||

| Drafted | 3 September 1992[1] | ||

| Signed | 13 January 1993[1] | ||

| Location | Paris and New York[1] | ||

| Effective | 29 April 1997[1] | ||

| Condition | Ratification by 65 states[2] | ||

| Signatories | 165[1] | ||

| Parties | 193[1] (List of state parties) Four UN states are not party: Egypt, Israel, North Korea and South Sudan. | ||

| Depositary | UN Secretary-General[3] | ||

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish[4] | ||

As of August 2022,[update] 193 states have become parties to the CWC and accept its obligations. Israel has signed but not ratified the agreement, while three other UN member states (Egypt, North Korea and South Sudan) have neither signed nor acceded to the treaty.[1][5] Most recently, the State of Palestine deposited its instrument of accession to the CWC on 17 May 2018. In September 2013, Syria acceded to the convention as part of an agreement for the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons.[6][7]

As of February 2021, 98.39% of the world's declared chemical weapons stockpiles had been destroyed.[8] The convention has provisions for systematic evaluation of chemical production facilities, as well as for investigations of allegations of use and production of chemical weapons based on the intelligence of other state parties.

Some chemicals which have been used extensively in warfare but have numerous large-scale industrial uses (such as phosgene) are highly regulated; however, certain notable exceptions exist. Chlorine gas is highly toxic, but being a pure element and widely used for peaceful purposes, is not officially listed as a chemical weapon. Certain state powers (e.g. the Assad regime of Syria) continue to regularly manufacture and implement such chemicals in combat munitions.[9] Although these chemicals are not specifically listed as controlled by the CWC, the use of any toxic chemical as a weapon (when used to produce fatalities solely or mainly through its toxic action) is in-and-of itself forbidden by the treaty. Other chemicals, such as white phosphorus,[10] are highly toxic but are legal under the CWC when they are used by military forces for reasons other than their toxicity.[11]

History

editThe CWC augments the Geneva Protocol of 1925, which bans the use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflicts, but not their development or possession.[12] The CWC also includes extensive verification measures such as on-site inspections, in stark contrast to the 1975 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), which lacks a verification regime.[13]

After several changes of name and composition, the ENDC evolved into the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in 1984.[14] On 3 September 1992 the CD submitted to the U.N. General Assembly its annual report, which contained the text of the Chemical Weapons Convention. The General Assembly approved the convention on 30 November 1992, and the U.N. Secretary-General then opened the convention for signature in Paris on 13 January 1993.[15] The CWC remained open for signature until its entry into force on 29 April 1997, 180 days after the deposit at the UN by Hungary of the 65th instrument of ratification.[16]

Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

editThe convention is administered by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which acts as the legal platform for specification of the CWC provisions.[17] The Conference of the States Parties is mandated to change the CWC and pass regulations on the implementation of CWC requirements. The Technical Secretariat of the organization conducts inspections to ensure compliance of member states. These inspections target destruction facilities (where constant monitoring takes place during destruction), chemical weapons production facilities which have been dismantled or converted for civil use, as well as inspections of the chemical industry. The Secretariat may furthermore conduct "investigations of alleged use" of chemical weapons and give assistance after use of chemical weapons.[citation needed]

The 2013 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the organization because it had, with the Chemical Weapons Convention, "defined the use of chemical weapons as a taboo under international law" according to Thorbjørn Jagland, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.[18][19]

Key points of the Convention

edit- Prohibition of production and use of chemical weapons

- Destruction (or monitored conversion to other functions) of chemical weapons production facilities

- Destruction of all chemical weapons (including chemical weapons abandoned outside the state parties territory)

- Assistance between State Parties and the OPCW in the case of use of chemical weapons

- An OPCW inspection regime for the production of chemicals which might be converted to chemical weapons

- International cooperation in the peaceful use of chemistry in relevant areas

Controlled substances

editThe convention distinguishes three classes of controlled substance,[20][21] chemicals that can either be used as weapons themselves or used in the manufacture of weapons. The classification is based on the quantities of the substance produced commercially for legitimate purposes. Each class is split into Part A, which are chemicals that can be used directly as weapons, and Part B, which are chemicals useful in the manufacture of chemical weapons. Separate from the precursors, the convention defines toxic chemicals as "[a]ny chemical which through its chemical action on life processes can cause death, temporary incapacitation or permanent harm to humans or animals. This includes all such chemicals, regardless of their origin or of their method of production, and regardless of whether they are produced in facilities, in munitions or elsewhere."[22]

- Schedule 1 chemicals have few, or no uses outside chemical weapons. These may be produced or used for research, medical, pharmaceutical or chemical weapon defence testing purposes but production at sites producing more than 100 grams per year must be declared to the OPCW. A country is limited to possessing a maximum of 1 tonne of these materials. Examples are sulfur mustard and nerve agents, and substances which are solely used as precursor chemicals in their manufacture. A few of these chemicals have very small scale non-military applications, for example, milligram quantities of nitrogen mustard are used to treat certain cancers.

- Schedule 2 chemicals have legitimate small-scale applications. Manufacture must be declared and there are restrictions on export to countries that are not CWC signatories. An example is thiodiglycol which can be used in the manufacture of mustard agents, but is also used as a solvent in inks.

- Schedule 3 chemicals have large-scale uses apart from chemical weapons. Plants which manufacture more than 30 tonnes per year must be declared and can be inspected, and there are restrictions on export to countries which are not CWC signatories. Examples of these substances are phosgene (the most lethal chemical weapon employed in WWI),[23] which has been used as a chemical weapon but which is also a precursor in the manufacture of many legitimate organic compounds (e.g. pharmaceutical agents and many common pesticides), and triethanolamine, used in the manufacture of nitrogen mustard but also commonly used in toiletries and detergents.

Many of the chemicals named in the schedules are simply examples from a wider class, defined with Markush like language. For example, all chemicals in the class "O-Alkyl (<=C10, incl. cycloalkyl) alkyl (Me, Et, n-Pr or i-Pr)- phosphonofluoridates chemicals" are controlled, despite only a few named examples being given, such as Soman.

This can make it more challenging for companies to identify if chemicals they handle are subject to the CWC, especially Schedule 2 and 3 chemicals (such as Alkylphosphorus chemicals). For example, Amgard 1045 is a flame retardant, but falls within Schedule 2B[24] as part of Alkylphosphorus chemical class. This approach is also used in controlled drug legislation in many countries and are often termed "class wide controls" or "generic statements".

Due to the added complexity these statements bring in identifying regulated chemicals, many companies choose to carry out these assessments computationally, examining the chemicals structure using in silico tools which compare them to the legislation statements, either with in house systems maintained a company or by the use commercial compliance software solutions.[25]

A treaty party may declare a "single small-scale facility" that produces up to 1 tonne of Schedule 1 chemicals for research, medical, pharmaceutical or protective purposes each year, and also another facility may produce 10 kg per year for protective testing purposes. An unlimited number of other facilities may produce Schedule 1 chemicals, subject to a total 10 kg annual limit, for research, medical or pharmaceutical purposes, but any facility producing more than 100 grams must be declared.[20][26]

The treaty also deals with carbon compounds called in the treaty "discrete organic chemicals", the majority of which exhibit moderate-high direct toxicity or can be readily converted into compounds with toxicity sufficient for practical use as a chemical weapon.[27] These are any carbon compounds apart from long chain polymers, oxides, sulfides and metal carbonates, such as organophosphates. The OPCW must be informed of, and can inspect, any plant producing (or expecting to produce) more than 200 tonnes per year, or 30 tonnes if the chemical contains phosphorus, sulfur or fluorine, unless the plant solely produces explosives or hydrocarbons.

Category definitions

editChemical weapons are divided into three categories:[28]

- Category 1 - based on Schedule 1 substances

- Category 2 - based on non-Schedule 1 substances

- Category 3 - devices and equipment designed to use chemical weapons, without the substances themselves

Member states

editBefore the CWC came into force in 1997, 165 states signed the convention, allowing them to ratify the agreement after obtaining domestic approval.[1] Following the treaty's entry into force, it was closed for signature and the only method for non-signatory states to become a party was through accession. As of March 2021, 193 states, representing over 98 percent of the world's population, are party to the CWC.[1] Of the four United Nations member states that are not parties to the treaty, Israel has signed but not ratified the treaty, while Egypt, North Korea, and South Sudan have neither signed nor acceded to the convention. Taiwan, though not a member state, has stated on 27 August 2002 that it fully complies with the treaty.[29][30][31]

Key organizations of member states

editMember states are represented at the OPCW by their Permanent Representative. This function is generally combined with the function of Ambassador. For the preparation of OPCW inspections and preparation of declarations, member states have to constitute a National Authority.[32]

World stockpile of chemical weapons

editA total of 72,304 metric tonnes of chemical agent, and 97 production facilities have been declared to OPCW.[8]

Treaty deadlines

editThe treaty set up several steps with deadlines toward complete destruction of chemical weapons, with a procedure for requesting deadline extensions. No country reached total elimination by the original treaty date although several have finished under allowed extensions.[33]

| Phase | % Reduction | Deadline | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1% | April 2000 | |

| II | 20% | April 2002 | Complete destruction of empty munitions, precursor chemicals, filling equipment and weapons systems |

| III | 45% | April 2004 | |

| IV | 100% | April 2007 | No extensions permitted past April 2012 |

Progress of destruction

editAt the end of 2019, 70,545 of 72,304 (97.51%) metric tonnes of chemical agent have been verifiably destroyed. More than 57% (4.97 million) of chemical munitions and containers have been destroyed.[34]

Seven state parties have completed the destruction of their declared stockpiles: Albania, India, Iraq, Libya, Syria, the United States, and an unspecified state party (believed to be South Korea). Russia also completed the destruction of its declared stockpile. According to the US Arms Control Association, the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in 2018 and the poisoning of Alexei Navalny in 2020 indicated that Russia maintained an illicit chemical weapons program.[35]

Japan and China in October 2010 began the destruction of World War II era chemical weapons abandoned by Japan in China by means of mobile destruction units and reported destruction of 35,203 chemical weapons (75% of the Nanjing stockpile).[36][37]

| Country and link to detail article | Date of accession/ entry into force |

Declared stockpile (Schedule 1) (tonnes) |

% OPCW-verified destroyed (date of full destruction) |

Destruction deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 29 April 1997 | 17[38] | 100% (July 2007)[38] | |

| South Korea | 29 April 1997 | 3,000–3,500[39] | 100% (July 2008)[39] | |

| India | 29 April 1997 | 1,044[40] | 100% (March 2009)[41] | |

| Libya | 5 February 2004 | 25[42] | 100% (January 2014)[42] | |

| Syria (government held) | 14 October 2013[43] | 1,040[44] | 100% (August 2014)[44] | |

| Russia | 5 December 1997 | 40,000[45] | 100% (September 2017)[46] | |

| United States | 29 April 1997 | 33,600[47] | 100% (July 2023)[48] | |

| Iraq | 12 February 2009 | remnant munitions[49] | 100% (March 2018)[50] | |

| Japan (in China) | 29 April 1997 | - | 66.97% (as of September 2022)[51] | 2027[52] |

Iraqi stockpile

editThe U.N. Security Council ordered the dismantling of Iraq's chemical weapon stockpile in 1991. By 1998, UNSCOM inspectors had accounted for the destruction of 88,000 filled and unfilled chemical munitions, over 690 metric tons of weaponized and bulk chemical agents, approximately 4,000 tonnes of precursor chemicals, and 980 pieces of key production equipment.[53] The UNSCOM inspectors left in 1998.

In 2009, before Iraq joined the CWC, the OPCW reported that the United States military had destroyed almost 5,000 old chemical weapons in open-air detonations since 2004.[54] These weapons, produced before the 1991 Gulf War, contained sarin and mustard agents but were so badly corroded that they could not have been used as originally intended.[55]

When Iraq joined the CWC in 2009, it declared "two bunkers with filled and unfilled chemical weapons munitions, some precursors, as well as five former chemical weapons production facilities" according to OPCW Director General Rogelio Pfirter.[41] The bunker entrances were sealed with 1.5 meters of reinforced concrete in 1994 under UNSCOM supervision.[56] As of 2012, the plan to destroy the chemical weapons was still being developed, in the face of significant difficulties.[49][56] In 2014, ISIS took control of the site.[57]

On 13 March 2018, the Director-General of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, congratulated the Government of Iraq on the completion of the destruction of the country's chemical weapons remnants.[50]

Syrian destruction

editFollowing the August 2013 Ghouta chemical attack,[58] Syria, which had long been suspected of possessing chemical weapons, acknowledged them in September 2013 and agreed to put them under international supervision.[59] On 14 September Syria deposited its instrument of accession to the CWC with the United Nations as the depositary and agreed to its provisional application pending entry into force effective 14 October.[60][61] An accelerated destruction schedule was devised by Russia and the United States on 14 September,[62] and was endorsed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2118[63] and the OPCW Executive Council Decision EC-M-33/DEC.1.[64] Their deadline for destruction was the first half of 2014.[64] Syria gave the OPCW an inventory of its chemical weapons arsenal[65] and began its destruction in October 2013, 2 weeks before its formal entry into force, while applying the convention provisionally.[66][67] All declared Category 1 materials were destroyed by August 2014.[44] However, the Khan Shaykhun chemical attack in April 2017 indicated that undeclared stockpiles probably remained in the country. A chemical attack on Douma occurred on 7 April 2018 that killed at least 49 civilians with scores injured, and which has been blamed on the Assad government.[68][69][70]

Controversy arose in November 2019 over the OPCW's finding on the Douma chemical weapons attack when Wikileaks published emails by an OPCW staff member saying a report on this incident "misrepresents the facts" and contains "unintended bias". The OPCW staff member questioned the report's finding that OPCW's inspectors had "sufficient evidence at this time to determine that chlorine, or another reactive chlorine-containing chemical, was likely released from cylinders".[71] The staff member alleged this finding was "highly misleading and not supported by the facts" and said he would attach his own differing observations if this version of the report was released. On 25 November 2019, OPCW Director General Fernando Arias, in a speech to the OPCW's annual conference in The Hague, defended the Organization's report on the Douma incident, stating "While some of these diverse views continue to circulate in some public discussion forums, I would like to reiterate that I stand by the independent, professional conclusion" of the probe.[72]

Financial support for destruction

editFinancial support for the Albanian and Libyan stockpile destruction programmes was provided by the United States. Russia received support from a number of countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Canada; with some $2 billion given by 2004. Costs for Albania's program were approximately US$48 million. The United States has spent $20 billion and expected to spend a further $40 billion.[73]

Known chemical weapons production facilities

editFourteen states parties declared chemical weapons production facilities (CWPFs):[34][74]

- 1 non-disclosed state party (referred to as "A State Party" in OPCW-communications; said to be South Korea)[75]

Currently all 97 declared production facilities have been deactivated and certified as either destroyed (74) or converted (23) to civilian use.[34]

See also

editRelated international law

edit- Australia Group of countries and the European Commission that helps member nations identify exports which need to be controlled so as not to contribute to the spread of chemical and biological weapons

- 1990 US-Soviet Arms Control Agreement

- General-purpose criterion, a concept in international law that broadly governs international agreements with respect to chemical weapons

- Geneva Protocol, a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons among signatory states in international armed conflicts

Worldwide treaties for other types of weapons of mass destruction

edit- Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) (states parties)

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) (states parties)

- Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) (states parties)

Chemical weapons

editRelated remembrance day

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction". United Nations Treaty Collection. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 21.

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 23.

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 24.

- ^ "Angola Joins the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons". OPCW. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Resolution 2118 (2013)" (doc). United Nations documents. United Nations. 27 September 2013. p. 1. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

Noting that on 14 September 2013, the Syrian Arab Republic deposited with the Secretary-General its instrument of accession to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (Convention) and declared that it shall comply with its stipulations and observe them faithfully and sincerely, applying the Convention provisionally pending its entry into force for the Syrian Arab Republic

- ^ "U.S. sanctions Syrian officials for chemical weapons attacks". Reuters. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ a b "OPCW by the Numbers". Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism". 24 August 2016.

- ^ "'White phosphorus not used as chemical weapon in Syria'". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Paul Reynolds (16 November 2005). "White phosphorus: weapon on the edge". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Text of the 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Feakes, Daniel (2017). "The Biological Weapons Convention". Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics). 36 (2): 621–628. doi:10.20506/rst.36.2.2679. ISSN 0253-1933. PMID 30152458. S2CID 52100050.

- ^ The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, THE HARVARD SUSSEX PROGRAM ON CBW ARMAMENT AND ARMS LIMITATION

- ^ NATO. "The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), opens for signature". NATO. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Herby, Peter (30 April 1997). "Chemical Weapons Convention enters into force - ICRC". International Review of the Red Cross. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ The Intersection of Science and Chemical Disarmament, Beatrice Maneshi and Jonathan E. Forman, Science & Diplomacy, 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Syria chemical weapons monitors win Nobel Peace Prize". BBC News. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Official press release from Nobel prize Committee". Nobel Prize Organization. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Monitoring Chemicals with Possible Chemical Weapons Applications" (PDF). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. 7 December 2014. Fact sheet 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Annex on Chemicals". OPCW.

- ^ "CWC Article II. Definitions and Criteria". Chemical Weapons Convention. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "CDC Facts about Phosgene". Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "Most Traded Scheduled Chemicals 2022". OPCW.

- ^ "Regulated Chemicals | Controlled Substance Lists | Scitegrity". www.scitegrity.com.

- ^ Jean Pascal Zanders, John Hart, Richard Guthrie (October 2003). Non-Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention - Lessons from and for Iraq (PDF) (Report). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. p. 45. Policy Paper No. 5. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Chemical Weapons Convention". www.chemlink.com.au.

- ^ "The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) at a Glance | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org.

- ^ "Taiwan fully supports Chemical Weapons Convention". BBC. 27 August 2002. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ "China Chemical Chronology" (PDF). Washington, D.C. United States: Nuclear Threat Initiative. June 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ "Taiwan Overview". Washington, D.C. United States: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies. 6 September 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2024 – via Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- ^ "Chemical Weapons Convention". OPCW. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Russian President Vladimir Putin has announced that Russia is destroying its last supplies of chemical weapons": SOPHIE WILLAIMS, Russia destroys ALL chemical weapons and calls on AMERICA to do the same, Express, 27-9-2017.

- ^ a b c "OPCW chief announces destruction of over 96% of chemical weapons in the world". Tass. Tass.

- ^ "Syria, Russia, and the Global Chemical Weapons Crisis". Arms Control Association. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Opening Statement by the Director-General to the Conference of the States Parties at its Sixteenth Session" (PDF). OPCW. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Executive Council 61, Decision 1. OPCW. 2010

- ^ a b "Albania the First Country to Destroy All Its Chemical Weapons". OPCW. 12 July 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b Schneidmiller, Chris (17 October 2008). "South Korea Completes Chemical Weapons Disposal". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "India Country Profile – Chemical". Nuclear Threat Initiative. February 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b Schneidmiller, Chris (27 April 2009). "India Completes Chemical Weapons Disposal; Iraq Declares Stockpile". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Libya Completes Destruction of Its Category 1 Chemical Weapons". OPCW. 4 February 2014.

- ^ Syria applied the convention provisionally from 14 September 2013

- ^ a b c "OPCW: All Category 1 Chemicals Declared by Syria Now Destroyed". OPCW. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "Chemical Weapons Destruction". Government of Canada – Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. 16 October 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "OPCW Director-General Commends Major Milestone as Russia Completes Destruction of Chemical Weapons Stockpile under OPCW Verification". OPCW. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Contreras, Evelio (17 March 2015). "U.S. to begin destroying its stockpile of chemical weapons in Pueblo, Colorado". CNN. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "OPCW confirms: All declared chemical weapons stockpiles verified as irreversibly destroyed". OPCW. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Progress report on the preparation of the destruction plan for the al Muthanna bunkers" (PDF). OPCW. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b "OPCW Director-General Congratulates Iraq on Complete Destruction of Chemical Weapons Remnants".

- ^ "OPCW Executive Council and Director-General Review Progress on Destruction of Abandoned Chemical Weapons in China". OPCW. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Position Paper on the Chemical Weapons Abandoned by Japan in China". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 24 March 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Iraq Country Profile – Chemical". Nuclear Threat Initiative. April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Chivers, C.J. (22 November 2014). "Thousands of Iraq Chemical Weapons Destroyed in Open Air, Watchdog Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Shrader, Katherine (22 June 2006). "New Intel Report Reignites Iraq Arms Fight". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b Tucker, Jonathan B. (17 March 2010). "Iraq Faces Major Challenges in Destroying Its Legacy Chemical Weapons". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Isis seizes former chemical weapons plant in Iraq". The Guardian. Associated Press. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Borger, Julian; Wintour, Patrick (9 September 2013). "Russia calls on Syria to hand over chemical weapons". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Barnard, Anne (10 September 2013). "In Shift, Syrian Official Admits Government Has Chemical Arms". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Depositary Norification" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Secretary-General Receives Letter from Syrian Government Informing Him President Has Signed Legislative Decree for Accession to Chemical Weapons Convention". United Nations. 12 September 2013.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (14 September 2013). "U.S. and Russia Reach Deal to Destroy Syria's Chemical Arms". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Michael Corder (27 September 2013). "Syrian Chemical Arms Inspections Could Begin Soon". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Decision: Destruction of Syrian Chemical Weapons" (PDF). OPCW. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ "Syria chemical arms removal begins". BBC News. 6 October 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Kerry 'very pleased' at Syria compliance over chemical weapons". NBC News. 7 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Mariam Karouny (6 October 2013). "Destruction of Syrian chemical weapons begins: mission". Reuters. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Nicole Gaouette (9 April 2018). "Haley says Russia's hands are 'covered in the blood of Syrian children'". CNN.

- ^ "Suspected Syria chemical attack kills 70". BBC News. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "OPCW confirms chemical weapons use in Douma, Syria". DW. Agence France-Presse/Associated Press. 1 March 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Greg Norman (2019). "Syria watchdog accused of making misleading edits in report on chemical weapons attack". Foxnews.com. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ CBS/AFP (2019). "Chemical weapons watchdog OPCW defends Syria report as whistleblower claims bias". cbsnews.com. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "Russia, U.S. face challenge on chemical weapons", Stephanie Nebehay, Reuters, 7 August 2007, accessed 7 August 2007

- ^ "Eliminating Chemical Weapons and Chemical Weapons Production Facilities" (PDF). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. November 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ "Confidentiality and verification: the IAEA and OPCW" (PDF). VERTIC. May–June 2004. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

External links

edit- Full text of the Chemical Weapons Convention, OPCW

- Online text of the Chemical Weapons Convention: Articles, Annexes including Chemical Schedules, OPCW

- Fact Sheets Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, OPCW

- Chemical Weapons Convention: Ratifying Countries, OPCW

- Chemical Weapons Convention Website, United States

- The Chemical Weapons Convention at a Glance Archived 16 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Arms Control Association

- Chemical Warfare Chemicals and Precursors, Chemlink Pty Ltd, Australia

- Introductory note by Michael Bothe, procedural history note and audiovisual material on the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- Lecture by Santiago Oñate Laborde entitled The Chemical Weapons Convention: an Overview in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law