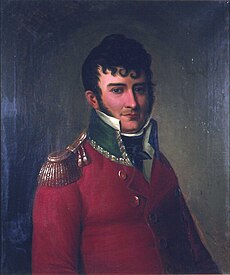

Christian Magnus Falsen (14 September 1782 – 13 January 1830) was a Norwegian constitutional father, statesman, jurist, and historian. He was an important member of the Norwegian Constituent Assembly and was one of the writers of the Constitution of Norway.

Christian Magnus Falsen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 September 1782 Christiania, Norway |

| Died | 13 January 1830 (aged 47) Christiania, Norway |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Occupation | Jurist |

| Known for | Father of the Norwegian Constitution |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Parent | Enevold de Falsen (father) |

Falsen has been named the father of the Norwegian Constitution.[1][2][3] Falsen's constitutional draft contained an almost literal copy of part of the U.S. Declaration of Independence: "All men are born free and equal: they have certain natural, essential and unchangeable rights. These are freedom, security, and property".[4] Falsen's draft became the single most important direct source to the 1814 constitution.[5]

Biography

editChristian Magnus Falsen was born in Christiania, now Oslo, Norway. He was the son of Enevold de Falsen (1755–1808), a dramatist and author of a war song Til vaaben. In 1802, he graduated with a degree in law at the University of Copenhagen. In 1807, Christian Magnus Falsen was appointed a barrister. In 1808 he became circuit judge at Follo and lived in Ås, Akershus Akershus, Norway.[6][7]

After Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden in 1814 he played an important part in politics. Falsen led the Independent Party (Selvstendighetspartiet) that wanted complete independence and was prepared to resist Sweden militarily. He upheld King Christian Frederick and, after the separation of Norway from Denmark, assisted in drafting a constitution for Norway. During the drafting of the Norwegian constitution, Falsen was one of the principle authors of the Jew clause, which prohibited Jews from entering Norway.,[8] This document was modeled upon that adopted by France in 1791 and which was approved on 17 May 1814 by the Norwegian Constituent Assembly (Riksforsamlingenat) at Eidsvoll. He was also strongly inspired by Thomas Jefferson and the Constitution of the United States of America. He is often called Father of the Norwegian Constitution — Grunnlovens far. [9][10] Falsen had a son in the spring of 1814 who he named Georg Benjamin, in honor of U.S. presidents George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.[11]

Falsen held a seat in the Storting and generally favored conservative political positions. In 1822 he was appointed Attorney General of the Kingdom, a post which he held for three years. In 1825 he became bailiff for Bergen, and in 1827 president of the Supreme Court. In 1828 he suffered from a stroke and did not return to the office. Christian Magnus Falsen is buried at Gamlebyen Churchyard. Next to his gravestone is the gravestone of his second wife.

In 1804, he married Anna Birgitte Munch (1787-1810), with whom he had the son Enevold Munch Falsen (1810–80). In 1811, after her death, he married Elisabeth Severine Böckmann (1782-1848). She was the widow of Brede Stoltenberg, a brother of the tradesman Gregers Stoltenberg. With her he had the children Henrik Anton Falsen (1813–66) and Elisabeth Christine Falsen (1820–76).[12]

American influence

editFalsen's admiration for the United States of America was rooted in its democratic ideals, legal system, and the innovative spirit that defined the early years of the U.S. Falsen's fascination with the United States began at a young age through the influence of his father. From his father, Enevold De Falsen, he had absorbed his American ideals. He studied American history throughout his life.[13][14] He studied law at the University of Copenhagen, where he had access to an extensive collection of books and writings on American history and political philosophy. Falsen delved into the works of influential American figures such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton, which exposed him to the revolutionary ideas that shaped the birth of the United States.[15]

Falsen later wrote the first biography of George Washington in the Norwegian language, which was a highly laudatory biographical sketch of George Washington.[16][17] In his Washington biography, Falsen described him as the epitome of moral strength, marked by a serious thoughtfulness and an extraordinary self-mastery and unselfishness based on the laws of honor and common sense.[18]

Falsen has been nicknamed "Norway's James Madison". He was well-orientated on the political and constitutional developments in America. He was impressed by the American independence movement. Falsen also argued for a bicameral system similar to what he called the "world's greatest constitution": the American Constitution.[19]

Falsen was chairman of the Constituent Assembly's committee charged with drafting the constitution and at times served as the president of the assembly. The constitutional draft by Johan Gunder Adler and Falsen, the Adler-Falsen draft, was overwhelmingly inspired by the U.S. Constitution.[20] Falsen's draft became the single most important direct source of the Norwegian Constitution.[21] The constitutional draft contained an almost literal copy of the U.S. Declaration of Independence: "All men are born free and equal: they have certain natural, essential and unchangeable rights. These are freedom, security, and property".[22]

The draft incorporated a word-for-word translation of Article 30 of the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, articulating the principle of the separation of powers. Other provisions also showed parallels to the U.S. Constitution, including listing the parliament's legislative powers and its method of compensating lawmakers. The Norwegian constitutional rule of parliamentary immunity from arrests and the first article of the U.S. Constitution were particularly striking. The same was true of the rules for impeaching cabinet members.[23][24] It also included corresponding parts of the New Hampshire Constitution. The sentence "Laws, not men should govern" was directly translated from the Massachusetts Constitution.[25]

When Norway joined the U.S. in 1814 as one of the world's first constitutional states, a proposal was made to the Constitutional Assembly that Norway would adopt The Star-Spangled Banner as a new national flag, with five stars, one for each Norwegian diocese. The proposal did not pass.[26]

Falsen was a great admirer of U.S. Presidents George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. In 1814, he baptized his son Georg Benjamin in their honor.[27][28][29]

Falsen would later publish a pamphlet on July 4, 1814, about the prospects of a new state where he pointed the American model: "For seven years they fought against the terrible odds. Not in vain, brethren, should these gorgeous examples shine before our eyes!".[30][31]

In 1817, Falsen wrote that the Norwegian Constitution "in particular when it comes to the representation of the people, it almost exclusively kept the American Constitution in view."[32]

Note

editThis article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

References

edit- ^ Billias, George Athan (2011). American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776-1989. NYU Press. Page 144. ISBN 9780814725177.

- ^ Müßig, Ulrike (2018). Reconsidering Constitutional Formation II Decisive Constitutional Normativity: From Old Liberties to New Precedence. Springer International Publishing. Page 287. ISBN 9783319730370.

- ^ Roos, Merethe and Christina Matthiesen (2021). Exploring Textbooks and Cultural Change in Nordic Education 1536–2020. Brill. Page 136. ISBN 9789004449558.

- ^ Fuglestad, Eirik Magnus (2018). Private Property and the Origins of Nationalism in the United States and Norway: The Making of Propertied Communities. Springer. Page 101. ISBN 9783319899503.

- ^ Müßig, Ulrike (2018). Reconsidering Constitutional Formation II Decisive Constitutional Normativity: From Old Liberties to New Precedence. Springer International Publishing. Page 287. ISBN 9783319730370.

- ^ Christian Magnus Falsen, Embedsperson og Politiker (Norsk biografisk leksikon)

- ^ Christian Magnus Falsen (Eidvoll 1812)

- ^ "The abolition of the Jews Act in Norway's Basic Law 1814 - 1851 - 2001. Brief history and description of the documentation".

- ^ Christian Magnus Falsen- Grunnlovens far (Stortinget)

- ^ Selvstendighetspartiet (Norsk partipolitisk leksikon)

- ^ Wasser, Henry H. and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 50. ISBN 9781512806939.

- ^ Familie: Christian Magnus Falsen/Elisabeth Severine Bøckmann (Hemneslekt)

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 26. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). USA i norsk historie: 1000 - 1776 - 1976. Det Norske Samlaget. Page 54. ISBN 8252105661.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 20. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Wasser, Henry and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica: Norwegian Contributions to American Studies, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 51. ISBN 9781512806939.

- ^ "Samtiden: tidsskrift for politik, litteratur og samfunnsspørsmål, vol. 57" (1948). University of Michigan. Page 231.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 27. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Jensen, Bjørn (1976). Møte med Amerika: 25 nordmenn oppfatter amerikansk historie og nåtid. University of Wisconsin–Madison. Page 38. ISBN 9788203086557.

- ^ Bijleveld, Nikolaj and Colin Grittner (2019). Reforming Senates: Upper Legislative Houses in North Atlantic Small Powers 1800-present. Routledge. ISBN 9781000706673.

- ^ Müßig, Ulrike (2018). Reconsidering Constitutional Formation II Decisive Constitutional Normativity: From Old Liberties to New Precedence. Springer International Publishing. Page 287. ISBN 9783319730370.

- ^ Fuglestad, Eirik Magnus (2018). Private Property and the Origins of Nationalism in the United States and Norway: The Making of Propertied Communities. Springer. Page 101. ISBN 9783319899503.

- ^ Billias, George Athan (2011). American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776-1989: A Global Perspective. NYU Press. Page 144. ISBN 9780814725177.

- ^ Wasser, Henry and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica: Norwegian Contributions to American Studies, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 50. ISBN 9781512806939.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 28. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Wasser, Henry and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica: Norwegian Contributions to American Studies, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 51. ISBN 9781512806939.

- ^ Jensen, Bjørn (1976). Møte med Amerika: 25 nordmenn oppfatter amerikansk historie og nåtid. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Page 38. ISBN 9788203086557.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 29. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Wasser, Henry and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica: Norwegian Contributions to American Studies, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 50. ISBN 9781512806939.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). The United States in Norwegian History. Greenwood Press. Page 30. ISBN 8200049728.

- ^ Skard, Sigmund (1976). USA i norsk historie: 1000 - 1776 - 1976. Det norske samlaget. Page 63. ISBN 8252105661.

- ^ Wasser, Henry and Sigmund Skard (2016). Americana Norvegica: Norwegian Contributions to American Studies, Volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 51. ISBN 9781512806939.

Other sources

edit- Daa, Ludvig Kristensen (1860) Magnus Falsen, et Bidrag til Norges Konstitutions Historie (Christiana)

- Vullum, Erik (1881) Kristian Magnus Falsen, Grundlovens Fader (Christiana)

- Indrebø, Gustav (1919) Det norske generalprokurørembættet: Chr. M. Falsen 1822-1825 (Christiana)

- Østvedt, Einar (1945) Christian Magnus Falsen: linjen i hans politikk. (Oslo: H. Aschehoug and co)

Related Reading

edit- Barton, H. Arnold (2002) Sweden and Visions of Norway: Politics and Culture 1814-1905 (Southern Illinois University Press) ISBN 978-0809324415