The Kingdom of Khotan was an ancient Buddhist Saka kingdom[a] located on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin (modern-day Xinjiang, China). The ancient capital was originally sited to the west of modern-day Hotan at Yotkan.[1][2] From the Han dynasty until at least the Tang dynasty it was known in Chinese as Yutian. This largely Buddhist kingdom existed for over a thousand years until it was conquered by the Muslim Kara-Khanid Khanate in 1006, during the Islamization and Turkicization of Xinjiang.

Kingdom of Khotan 于闐 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 300 BC–1006 | |||||||||

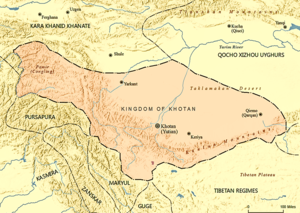

Map of the kingdom of Khotan circa 1000. | |||||||||

| Capital | Hotan | ||||||||

| Common languages | Khotanese[web 1] Gāndhārī[web 2] | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• c. 56 | Yulin: Jianwu period (25–56 AD) | ||||||||

• 969 | Nanzongchang (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Khotan established | c. 300 BC | ||||||||

• Established | c. 300 BC | ||||||||

• Yarkant attacks and annexes Khotan. Yulin abdicates and becomes king of Ligui | 56 | ||||||||

• Tibet invades and conquers Khotan | 670 | ||||||||

• Khotan held by the Muslim, Yūsuf Qadr Khān | 1006 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1006 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China Tajikistan | ||||||||

Built on an oasis, Khotan's mulberry groves allowed the production and export of silk and carpets, in addition to the city's other major products such as its famous nephrite jade and pottery. Despite being a significant city on the silk road as well as a notable source of jade for ancient China, Khotan itself is relatively small – the circumference of the ancient city of Khotan at Yōtkan was about 2.5 to 3.2 km (1.5 to 2 miles). Much of the archaeological evidence of the ancient city of Khotan however had been obliterated due to centuries of treasure hunting by local people.[3]

The inhabitants of Khotan spoke Khotanese, an Eastern Iranian language belonging to the Saka language, and Gandhari Prakrit, an Indo-Aryan language related to Sanskrit. There is debate as to how much Khotan's original inhabitants were ethnically and anthropologically Indo-Aryan and speakers of the Gāndhārī language versus the Saka, an Indo-European people of Iranian branch from the Eurasian Steppe. From the 3rd century onwards they also had a visible linguistic influence on the Gāndhārī language spoken at the royal court of Khotan. The Khotanese Saka language was also recognized as an official court language by the 10th century and used by the Khotanese rulers for administrative documentation.

Names

editThe kingdom of Khotan was given various names and transcriptions. The ancient Chinese called Khotan Yutian (于闐, its ancient pronunciation was gi̯wo-d'ien or ji̯u-d'ien)[3] also written as 于窴 and other similar-sounding names such as Yudun (于遁), Huodan (豁旦), and Qudan (屈丹). Sometimes they also used Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it respectively. Others include Huanna (渙那).[4] To the Tibetans in the seventh and eighth centuries, the kingdom was called Li (or Li-yul) and the capital city Hu-ten, Hu-den, Hu-then and Yvu-then.[5][6]

The name as written by the locals changed over time; in about the third century AD, the local people wrote Khotana in Kharoṣṭhī script, and Hvatäna in the Brahmi script some time later. From this came Hvamna and Hvam in their latest texts, where Hvam kṣīra or 'the land of Khotan' was the name given. Khotan became known to the west while the –t- was still unchanged, as is frequent in early New Persian. The local people also used Gaustana (Gosthana, Gostana, Godana, Godaniya or Kustana) under the influence of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, and Yūttina in the ninth century, when it was allied with the Chinese kingdom of Șacū (Shazhou or Dunhuang).[5][7]

Location and geography

editThe geographical position of the oasis was the main factor in its success and wealth. To its north is one of the most arid and desolate desert climates on the earth, the Taklamakan Desert, and to its south the largely uninhabited Kunlun Mountains (Qurum). To the east there were few oases beyond Niya, making travel difficult, and access is only relatively easy from the west.[3][8]

Khotan was irrigated from the Yurung-kàsh[9] and Kara-kàsh rivers, which water the Tarim Basin. These two rivers produce vast quantities of water, which made habitation possible in an otherwise arid climate. The location next to the mountain not only allowed irrigation for crops but also increased the fertility of the land, as the rivers reduced the gradient and deposited sediment on their banks, creating a more fertile soil. This more fertile soil increased the agricultural productivity that made Khotan famous for its cereal crops and fruit. Therefore, Khotan's lifeline was its proximity to the Kunlun mountain range, and without it Khotan would not have become one of the largest and most successful oasis cities along the Silk Roads.

The kingdom of Khotan was one of the many small states found in the Tarim Basin, which included Yarkand, Loulan (Shanshan), Turfan, the Kashgar, Karashahr, and Kucha (the last three, together with Khotan, made up the four Garrisons during the Tang dynasty). To the west were the Central Asian kingdoms of Sogdiana and Bactria. It was surrounded by powerful neighbours, such as the Kushan Empire, China, Tibet, and for a time the Xiongnu, all of which had exerted or tried to exert their influence over Khotan at various times.

History

editFrom an early period, the Tarim Basin had been inhabited by different groups of Indo-European speakers such as the Tocharians and Saka people.[10][11] Jade from Khotan had been traded into China for a long time before the founding of the city, as indicated by items made of jade from Khotan found in tombs from the Shang (Yin) and Zhou dynasties. The jade trade is thought to have been facilitated by the Yuezhi.[12]

Foundation legend

editThere are four versions of the legend of the founding of Khotan. It is important to note that these legends were not contemporary or primary accounts. They were written centuries after the kingdom was founded."[13] These may be found in accounts given by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang and in Tibetan translations of Khotanese documents. All four versions suggest that the city was founded around the third century BC by a group of Indians during the reign of Ashoka.[3][13] According to one version, the nobles of a tribe in ancient Taxila, who traced their ancestry to the deity Vaiśravaṇa, were said to have blinded Kunãla, a son of Ashoka. In punishment they were banished by the Mauryan emperor to the north of the Himalayas, where they settled in Khotan and elected one of their members as king. However war then ensued with another group from China whose leader then took over as king, and the two colonies merged.[3] In a different version, it was Kunãla himself who was exiled and founded Khotan.[14]

The legend suggests that Khotan was settled by people from northwest India and China, and may explain the division of Khotan into an eastern and western city since the Han dynasty.[3] Others however argued that the legend of the founding of Khotan is a fiction as it ignores the Iranian population, and that its purpose was to explain the Indian and Chinese influences that were present in Khotan in the 7th century AD.[15] By Xuanzang's account, it was believed that the royal power had been transmitted unbroken since the founding of Khotan, and evidence indicates that the kings of Khotan had used an Iranian-based word as their title since at least the 3rd century AD, suggesting that they may be speakers of an Iranian language.[16]

In the 1900s, Aurel Stein discovered Prakrit documents written in Kharoṣṭhī in Niya, and together with the founding legend of Khotan, Stein proposed that these people in the Tarim Basin were Indian immigrants from Taxila who conquered and colonized Khotan.[17] The use of Prakrit however may be a legacy of the influence of the Kushan Empire.[18] There were also Greek influences in early Khotan, based on evidence such as Hellenistic artworks found at various sites in the Tarim Basin, for example, the Sampul tapestry found near Khotan, tapestries depicting the Greek god Hermes and the winged pegasus found at nearby Loulan, as well as ceramics that may suggest influences from as far as the Hellenistic kingdom of Ptolemaic Egypt.[19][20] One suggestion is therefore that the early migrants to the region may have been an ethnically mixed people from the city of Taxila led by a Greco-Saka or an Indo-Greek leader, who established Khotan using the administrative and social organizations of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.[21][22] In Tibetan literature, a long list of Indian kings is preserved. Sten Konow, the Norwegian Indologist who critically examined the different versions of the tradition concluded as follows:

"Kustana, the son of Ashoka, is said to have founded the royal dynasty of Khotan. But Kustana's son Ye-u-la, who is said to have founded the capital of the kingdom is most probably identical with the king Yü-Lin mentioned in the Chinese chronicles as ruling over Khotan about the middle of the first century AD.

Ye-u-la was succeeded by his son Vijita Saṃbhava, with whom begins a long series of Khotan kings all begin with Vijita. If there is any truth in the Chinese statement that Wei-chi or Vijita was the family name of the kings, it is of interest to note that this 'Vijita' dynasty, according to the Tibetan tradition, begins where the Han annals place the foundation of the national Khotan kingdom.

Buddhism was introduced into Khotan in the fifth year of Vijita Saṃbhava. Eleven kings followed, and then came Vijita Dharma who was a powerful ruler and always engaged in war. Later, he became a Buddhist and retired to Kashgar. We know from Chinese sources that Kashgar had formerly developed great power, but it became dependent on Khotan during AD 220-264. It is then probable that this was the time of the powerful king Vijita-Dharma.

Vijita Dharma was followed on the throne by his son Vijita Siṃha, and the latter by his son Vijita-Kīrti. Vijita-Kīrti is said to have carried war into India and to have overthrown Saketa, together with king Kanika (or the king of Kanika) and the Guzan king Guzan here evidently stands for Kushāṇa."

[23] According to the oldest detailed Chinese and Tibetan texts (including a Tibetan text which may be contemporary), which we cannot distrust, the colonizing groups of exiled Indians (including the son and ministers of Emperor Ashoka) founded the Kingdom of Khotan.[24]

Arrival of the Saka

editSurviving documents from Khotan of later centuries indicate that the people of Khotan spoke the Saka language, an Eastern Iranian language that was closely related to the Sogdian language (of Sogdiana); as an Indo-European language, Saka was more distantly related to the Tocharian languages (also known as Agnean-Kuchean) spoken in adjoining areas of the Tarim Basin.[26] It also shared areal features with Tocharian. It is not certain when the Saka people moved into the Khotan area. Archaeological evidence from the Sampul tapestry of Sampul[27] (Shanpulu; سامپۇل بازىرى[28] / 山普鲁镇), near Khotan may indicate a settled Saka population in the last quarter of the first millennium BC,[29] although some have suggested they may not have moved there until after the founding of the city.[30] The Saka may have inhabited other parts of the Tarim Basin earlier – presence of a people believed to be Saka had been found in the Keriya region at Yumulak Kum (Djoumboulak Koum, Yuansha) around 200 km east of Khotan, possibly as early as the 7th century BC.[31][32]

The Saka people were known as the Sai (塞, sāi, sək in Old Sinitic) in ancient Chinese records.[33] These records indicate that they originally inhabited the Ili and Chu River valleys of modern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In the Chinese Book of Han, the area was called the "land of the Sai", i.e. the Saka.[34] According to the Sima Qian's Shiji, the Indo-European Yuezhi, originally from the area between Tängri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China,[35] were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu in 177-176 BC.[36][37][38][39] In turn the Yuezhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) south. The Saka crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria around 140 B.C.[40] Later the Saka would also move into Northern India, as well as other Tarim Basin sites like Khotan, Karasahr (Yanqi), Yarkand (Shache) and Kucha (Qiuci). One suggestion is that the Saka became Hellenized in the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and they or an ethnically mixed Greco-Scythians either migrated to Yarkand and Khotan, or a bit earlier from Taxila in the Indo-Greek Kingdom.[41]

Documents written in Prakrit dating to the 3rd century AD from neighbouring Shanshan show that the king of Khotan was given the title hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati.[16] This along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given as Khotanese kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the late Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick (d. 2001).[16] He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian."[16] Furthermore, he elaborated on the early name of Khotan:

The name of Khotan is attested in a number of spellings, of which the oldest form is hvatana, in texts of approximately the 7th to the 10th century AD written in an Iranian language itself called hvatana by the writers. The same name is attested also in two closely related Iranian dialects, Sogdian and Tumshuq...Attempts have accordingly been made to explain it as Iranian, and this is of some importance historically. My own preference is for an explanation connecting it semantically with the name Saka, for the Iranian inhabitants of Khotan spoke a language closely related to that used by the used by the Sakas in the north-west of India from the first century B.C. onwards.[16]

Later Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found in Khotan and Tumshuq (east of Kashgar).[42] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language dating mostly to the 10th century have been found in Dunhuang.[43]

Early period

editObv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya.

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum

In the 2nd century AD a Khotanese king helped the famous ruler Kanishka of the Kushan Empire of South Asia (founded by the Yuezhi people) to conquer the key town of Saket in the Middle kingdoms of India: [a]

Afterwards king Vijaya Krīti, for whom a manifestation of the Ārya Mañjuśrī, the Arhat called Spyi-pri who was propagating the religion (dharma) in Kam-śeṅ [a district of Khotan] was acting as pious friend, through being inspired with faith, built the vihāra of Sru-ño. Originally, King Kanika, the king of Gu-zar [Kucha] and the Li [Khotanese] ruler, King Vijaya Krīti, and others led an army into India, and when they captured the city called So-ked [Saketa], King Vijaya Krīti obtained many relics and put them in the stūpa of Sru-ño.

— The Prophecy of the Li Country.[44]

According to Chapter 96A of the Book of Han, covering the period from 125 BC to 23 AD, Khotan had 3,300 households, 19,300 individuals and 2,400 people able to bear arms.[45]

Eastern Han period

editMinted coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century AD bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit in the Kharosthi script, showing links of Khotan to India and China in that period.[16]

Khotan began to exert its power in the first century AD. It was first ruled by Yarkand, but revolted in 25-57 AD and took Yarkand and the territory as far as Kashgar, thereby gaining control over part of the southern Silk Road.[3] The town grew very quickly after local trade developed into the interconnected chain of silk routes across Eurasia.

During the Yongping period (58-76 AD), in the reign of Emperor Ming, Xiumo Ba, a Khotanese general, rebelled against Suoju (Yarkand), and made himself king of Yutian (in 60 AD). On the death of Xiumo Ba, Guangde, son of his elder brother, assumed power and then (in 61 AD) defeated Suoju (Yarkand). His kingdom became very prosperous after this. From Jingjue (Niya) northwest, as far as Kashgar thirteen kingdoms submitted to him. Meanwhile, the king of Shanshan (the Lop Nor region, capital Charklik) had also begun to prosper. From then on, these two kingdoms were the only major ones on the Southern Route in the whole region to the east of the Congling (Pamir Mountains).[46]

King Guangde of Khotan submitted to the Han dynasty in 73 AD. Khotan at the time had relations with the Xiongnu, who during the reign of Emperor Ming of Han (57-75 AD) invaded Khotan and forced the Khotanese court to pay them large annual amounts of tribute in the form of silk and tapestries.[47] When the Han military officer Ban Chao went to Khotan, he was received by the King with minimal courtesy. The soothsayer to the King suggested that he should demand the horse of Ban, and Ban killed the soothsayer on the spot. The King, impressed by Ban's action, then killed the Xiongnu agent in Khotan and offered his allegiance to Han.[48]

By the time the Han dynasty exerted its dominance over Khotan, the population had more than quadrupled. The Book of the Later Han, covering 6 to 189 AD, says:

The main centre of the kingdom of Yutian (Khotan) is the town of Xicheng ("Western Town", Yotkan). It is 5,300 li (c.2,204 km) from the residence of the Senior Clerk [in Lukchun], and 11,700 li (c.4,865 km) from Luoyang. It controls 32,000 households, 83,000 individuals, and more than 30,000 men able to bear arms.[46]

Han influence on Khotan, however, diminished when Han power declined.[web 3]

Tang dynasty

editThe Tang campaign against the oasis states began in 640 AD and Khotan submitted to the Tang emperor. The Four Garrisons of Anxi were established, one of them at Khotan.

The Tibetans later defeated the Chinese and took control of the Four Garrisons. Khotan was first taken in 665,[49] and the Khotanese helped the Tibetans to conquer Aksu.[50] Tang China later regained control in 692, but eventually lost control of the entire Western Regions after it was weakened considerably by the An Lushan Rebellion.

After the Tang dynasty, Khotan formed an alliance with the rulers of the Guiyi Circuit. The Buddhist entitites of Dunhuang and Khotan had a tight-knit partnership, with intermarriage between Dunhuang and Khotan's rulers. Dunhuang's Mogao grottos and Buddhist temples were also funded and sponsored by the Khotan royals, whose likenesses were drawn in the Mogao grottoes.[51]

Khotan was conquered by the Tibetan Empire in 792 and gained its independence in 851.[52]

The first recorded post-Tibetan King of Khotan was Viśa' Saṃbhava, who used the Chinese name Li Shengtian and claimed to a descendant of the Tang dynasty imperial family. While using the Indic-style title "lion king" (rajasimha) and the Near Eastern Emperor-like title "king of kings", Viśa' Saṃbhava also used the Chinese title huangdi (emperor) in Khotan's Chinese language court documents, and dressed in hats and robes of Chinese style. His son, Viśa' Śūra, used the combined title, "king of kings of China" (caiga rāṃdānä rrādi), portrayed himself as a Chinese emperor in portraiture, used Chinese-style imperial edicts signed with the character chi 勑 ("edict", in imitation of the Tang and Song dynasties' edicts), and used a seal inscribed "Han Son of Heaven of great Khotan" (大于闐漢天子).[53] Viśa' Saṃbhava married the daughter of Cao Yijin, the ruler of the Guiyi Circuit. Cao Yijin's grandson, Cao Yanlu, married the third daughter of Viśa' Saṃbhava.[54][55]

-

Indian deity on the obverse of a painted panel, most likely depicting Shiva. Khotanese artist Viśa Īrasangä or his father Viśa Baysūna, 7th century

-

Persian deity on the reverse of a painted panel, probably depicting the legendary hero Rustam. Khotanese artist Viśa Īrasangä or his father Viśa Baysūna, 7th century

-

Grotesque face, stucco, found at Khotan, 7th-8th century.

-

Human head ceramic with cow, Tang Dynasty. Hotan Cultural Museum, China

Turco-Islamic conquest of Buddhist Khotan

editIn the 10th century, the Iranic Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was the only city-state in the Tarim Basin that was not yet conquered by either the Turkic Uyghur Qocho Kingdom (Buddhist) or by the Turkic Kara-Khanid Khanate (Muslim). During the latter part of the tenth century, Khotan became engaged in a struggle against the Kara-Khanid Khanate. The Islamic conquests of the Buddhist cities east of Kashgar began with the conversion of the Karakhanid Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan to Islam in 934. Satuq Bughra Khan and later his son Musa directed endeavors to proselytize Islam among the Turks and engage in military conquests,[51][56] and a long war ensued between Islamic Kashgar and Buddhist Khotan.[57] Satuq Bughra Khan's nephew or grandson Ali Arslan was said to have been killed during the war with the Buddhists.[58] Khotan briefly took Kashgar from the Kara-Khanids in 970, and according to Chinese accounts, the King of Khotan offered to send in tribute to the Chinese court a dancing elephant captured from Kashgar.[59]

Accounts of the war between the Karakhanid and Khotan were given in Taẕkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams, written sometime in the period from 1700 to 1849 in the Eastern Turkic language (modern Uyghur) in Altishahr probably based on an older oral tradition. It contains a story about four Imams from Mada'in city (possibly in modern-day Iraq) who helped the Qarakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan, Yarkand, and Kashgar.[60] There were years of battles where "blood flows like the Oxus", "heads litter the battlefield like stones" until the "infidels" were defeated and driven towards Khotan by Yusuf Qadir Khan and the four Imams. The imams however were assassinated by the Buddhists prior to the last Muslim victory.[61] Despite their foreign origins, they are viewed as local saints by the current Muslim population in the region.[62] In 1006, the Muslim Kara-Khanid ruler Yusuf Kadir (Qadir) Khan of Kashgar conquered Khotan, ending Khotan's existence as an independent Buddhist state.[51] Some communications between Khotan and Song China continued intermittently, but it was noted in 1063 in a Song source that the ruler of Khotan referred to himself as kara-khan, indicating dominance of the Karakhanids over Khotan.[63]

It has been suggested Buddhists in Dunhuang, alarmed by the conquest of Khotan and ending of Buddhism there, sealed Cave 17 of the Mogao Caves containing the Dunhuang manuscripts so to protect them.[64] The Karakhanid Turkic Muslim writer Mahmud al-Kashgari recorded a short Turkic language poem about the conquest:

kälginläyü aqtïmïz

kändlär üzä čïqtïmïz

furxan ävin yïqtïmïz

burxan üzä sïčtïmïzEnglish translation:[64][67][68][69]

We came down on them like a flood,

We went out among their cities,

We tore down the idol-temples,

We shat on the Buddha's head!

According to Kashgari who wrote in the 11th century, the inhabitants of Khotan still spoke a different language and did not know the Turkic language well.[70][71] It is however believed that the Turkic languages became the lingua franca throughout the Tarim Basin by the end of the 11th century.[72]

By the time Marco Polo visited Khotan, which was between 1271 and 1275, he reported that "the inhabitants all worship Mohamet."[73][74]

Historical timeline

edit- The first inhabitants of the region appear to have been Indians from the Maurya Empire according to its founding legends.[3]

- The foundation of Khotan occurred when Kushtana, said to be a son of Ashoka, the Indian emperor belonging to the Maurya Empire settled there about 224 BC.[75]

- c.84 BC: Buddhism is reportedly introduced to Khotan.[76]

- c.56: Xian, the powerful and prosperous king of Yarkent, attacked and annexed Khotan. He transferred Yulin, its king, to become the king of Ligui, and set up his younger brother, Weishi, as king of Khotan.

- 61: Khotan defeats Yarkand. Khotan becomes very powerful after this and 13 kingdoms submitted to Khotan, which now, with Shanshan, became the major power on the southern branch of the Silk Route.

- 78: Ban Chao, a Chinese General, subdues the kingdom.

- 127: The Khotanese king Vijaya Krīti is said to have helped the Kushan Emperor Kanishka in his conquest of Saket in India.

- 127: The Chinese general Ban Yong attacked and subdued Karasahr; and then Kucha, Kashgar, Khotan, Yarkand, and other kingdoms, seventeen altogether, who all came to submit to China.

- 129: Fangqian, the king of Khotan, killed the king of Keriya, Xing. He installed his son as the king of Keriya. Then he sent an envoy to offer tribute to Han. The Emperor pardoned the crime of the king of Khotan, ordering him to hand back the kingdom of Keriya. Fangqian refused.

- 131: Fangqian, the king of Khotan, sends one of his sons to serve and offer tribute at the Chinese Imperial Palace.

- 132: The Chinese sent the king of Kashgar, Chenpan, who with 20,000 men, attacked and defeated Khotan. He beheaded several hundred people, and released his soldiers to plunder freely. He replaced the king [of Keriya] by installing Chengguo from the family of [the previous king] Xing, and then he returned.

- 151: Jian, the king of Khotan, was killed by Han chief clerk Wang Jing, who was in turn killed by Khotanese. Anguo, the son of Jian, was placed on the throne.

- 175: Anguo, the king of Khotan, attacked Keriya, and defeated it soundly. He killed the king and many others.[77]

- 195: The 'Western Regions' rebelled, and Khotan regained its independence.

- 399 Chinese pilgrim monk, Faxian, visits and reports on the active Buddhist community there.[78]

- 632: Khotan pays homage to imperial China, and becomes a vassal state.

- 644: Chinese pilgrim monk, Xuanzang, stays 7–8 months in Khotan and writes a detailed account of the kingdom.

- 670: Tibetan Empire invades and conquers Khotan (now known as one of the "four garrisons").

- c.670-673: Khotan governed by Tibetan Mgar minister.

- 674: King Fudu Xiong (Vijaya Sangrāma IV), his family and followers flee to China after fighting the Tibetans. They are unable to return.

- c.680 - c.692: 'Amacha Khemeg rules as regent of Khotan.

- 692: China under Wu Zetian reconquers the Kingdom from Tibet. Khotan is made a protectorate.

- 725: Yuchi Tiao (Vijaya Dharma III) is beheaded by the Chinese for conspiring with the Turks. Yuchi Fushizhan (Vijaya Sambhava II) is placed on the throne by the Chinese.

- 728: Yuchi Fushizhan (Vijaya Sambhava II) officially given the title "King of Khotan" by the Chinese emperor.

- 736: Fudu Da (Vijaya Vāhana the Great) succeeds Yuchi Fushizhan and the Chinese emperor bestows a title on his wife.

- c. 740: King Yuchi Gui (Wylie: btsan bzang btsan la brtan) succeeds Fudu Da (Vijaya Vāhana) and begins persecution of Buddhists. Khotanese Buddhist monks flee to Tibet, where they are given refuge by the Chinese wife of King Mes ag tshoms. Soon after, the queen died in a smallpox epidemic and the monks had to flee to Gandhara.[79]

- 740: Chinese emperor bestows a title on wife of Yuchi Gui.

- 746: The Prophecy of the Li Country is completed and later added to the Tibetan Tengyur.

- 756: Yuchi Sheng hands over the government to his younger brother, Shihu (Jabgu) Yao.

- 786 to 788: Yuchi Yao still ruling Khotan at the time of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Wukong's visit to Khotan.[80]

- 934: Viśa' Saṃbhava marries the daughter of Cao Yijin, the ruler of the Guiyi Circuit of Dunhuang.

- 969: The son of King Viśa' Saṃbhava named Zongchang sends a tribute mission to China.

- 971: A Buddhist priest (Jixiang) brings a letter from the king of Khotan to the Chinese emperor offering to send a dancing elephant which he had captured from Kashgar.

- 1006: Khotan held by the Muslim Yūsuf Qadr Khān, a brother or cousin of the Muslim ruler of Kāshgar and Balāsāghūn.[81]

- Between 1271 and 1275: Marco Polo visits Khotan.[82]

List of rulers

editNote:- Some names are in modern Mandarin pronunciations based on ancient Chinese records and Time period of rulers is in CE.

- Yu Lin - 23 BCE

- Jun De - 57 BCE

- Gurgamoya - 30 to 60 CE

- Xiu Moba - 60

- Guang De - 60

- Vijaya Krīti (Fang Qian) - 110

- Jian - 132

- An Guo - 152

- Qiu Ren - 446

- Polo the Second - 471

- Sangrāma the Third (Sanjuluomo) - 477

- She Duluo - 500

- Viśa' Yuchi - 530

- Vijayavardhana (Bei Shilian)[83] - 590

- Viśa' Wumi - 620

- Fudu Xin - 642

- Vijaya Sangrāma IV (Fudu Xiong) - 665

- Viśvajita (Viśa' Jing) - 691

- Vijaya Dharma III (Viśa' Tiao) - 724

- Vijaya Sambhava II (Fu Shizhan) - 725

- Vijaya Vāhana the Great (Fudu Da) - 736

- Viśa' Gui - 740

- Viśa' Sheng - 745

- Viśvavāhana (Viśa' Vāhaṃ) - 764

- Viśa' Kīrti - 791

- Viśa' Chiye - 829

- Viśvānanda (Viśa' Nanta) - 844

- Viśa' Wana - 859

- Viśa' Piqiluomo - 888

- Viśa' Saṃbhava - 912

- Viśa' Śūra - 967

- Viśa' Dharma - 978

- Viśa' Sangrāma - 986

- Viśa' Sagemayi - 999 to 1006

Buddhism

editThe kingdom was one of the major centres of Buddhism, and up until the 11th century, the vast majority of the population was Buddhist.[84] Initially, the people of the kingdom were not Buddhist, and Buddhism was said to have been adopted in the reign of Vijayasambhava in the first century BC, some 170 years after the founding of Khotan.[85] However, an account by the Han general Ban Chao suggested that the people of Khotan in 73 AD still appeared to practice Mazdeism or Shamanism.[15][86] His son Ban Yong who spent time in the Western Regions also did not mention Buddhism there, and with the absence of Buddhist art in the region before the beginning of Eastern Han, it has also been suggested that Buddhism may not have been adopted in the region until the middle of the second century AD.[86]

The kingdom is primarily associated with the Mahayana.[87][88] According to the Chinese pilgrim Faxian who passed through Khotan in the fourth century:

The country is prosperous and the people are numerous; without exception they have faith in the Dharma and they entertain one another with religious music. The community of monks numbers several tens of thousands and they belong mostly to the Mahayana.[web 3]

It differed in this respect to Kucha, a Śrāvakayāna-dominated kingdom on the opposite side of the desert. Faxian's account of the city states it had fourteen large and many small viharas.[89] Many foreign languages, including Chinese, Sanskrit, Prakrits, Apabhraṃśas and Classical Tibetan were used in cultural exchange. A number of Buddhist monks who played an important role in the transmission of Buddhism in China had their origins in Khotan including Śikṣānanda and Śīladharma.[90][91]

Christianity

editAccording to the 11th-century Persian historian Gardizi, there were two East Syriac Christian churches within the kingdom's territory in the mid 5th–11th century, one inside the city of Khotan and one outside the city. A Christian cemetery has also been found in Khotan. In the Taḏkera of Maḥmūd-Karam Kābolī, it is recorded that Khotan was governed by a Christian ruler in the middle of the 12th century. Despite being a source of dubious historical value, this statement of the Taḏkera has been accepted as authentic by Bertold Spuler. A Chinese-manufactured Melkite cross with Greek inscription was bought at Khotan during the Mongol period.[92] A supposed reference to Christianity in a Khotanese text has been proved illusory by Ronald Erich Emmerick.[93]

Social and economic life

editDespite scant information on the socio-political structures of Khotan, the shared geography of the Tarim city-states and similarities in archaeological findings throughout the Tarim Basin enable some conclusions on Khotanese life.[94] A seventh-century Chinese pilgrim named Xuanzang described Khotan as having limited arable land but apparently particularly fertile, able to support "cereals and producing an abundance of fruits".[95] He further commented that the city "manufactures carpets and fine-felts and silks" as well as "dark and white jade". The city's economy was chiefly based upon water from oases for irrigation and the manufacture of traded goods.[96]

Xuanzang also praised the culture of Khotan, commenting that its people "love to study literature", and said "[m]usic is much practiced in the country, and men love song and dance." The "urbanity" of the Khotan people is also mentioned in their dress, that of 'light silks and white clothes' as opposed to more rural "wools and furs".[95]

Silk

editKhotan was the first place outside of inland China to begin cultivating silk. The legend, repeated in many sources, and illustrated in murals discovered by archaeologists, is that a Chinese princess brought silkworm eggs hidden in her hair when she was sent to marry the Khotanese king. This probably took place in the first half of the 1st century AD but is disputed by a number of scholars.[97]

One version of the story is told by the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang who describes the covert transfer of silkworms to Khotan by a Chinese princess. Xuanzang, on his return from India between 640 and 645, crossed Central Asia passing through the kingdoms of Kashgar and Khotan (Yutian in Chinese).[98]

According to Xuanzang, the introduction of sericulture to Khotan occurred in the first quarter of the 5th century. The King of Khotan wanted to obtain silkworm eggs, mulberry seeds and Chinese know-how - the three crucial components of silk production. The Chinese court had strict rules against these items leaving China, to maintain the Chinese monopoly on silk manufacture. Xuanzang wrote that the King of Khotan asked for the hand of a Chinese princess in marriage as a token of his allegiance to the Chinese emperor. The request was granted, and an ambassador was sent to the Chinese court to escort the Chinese princess to Khotan. He advised the princess that she would need to bring silkworms and mulberry seeds in order to make herself robes in Khotan and to make the people prosperous. The princess concealed silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds in her headdress and smuggled them through the Chinese frontier. According to his text, silkworm eggs, mulberry trees and weaving techniques passed from Khotan to India, and from there eventually reached Europe.[99]

Jade

editKhotan, throughout and before the Silk Roads period, was a prominent trading oasis on the southern route of the Tarim Basin – the only major oasis "on the sole water course to cross the desert from the south".[100] Aside from the geographical location of the towns of Khotan it was also important for its wide renown as a significant source of nephrite jade for export to China.

There has been a long history of trade of jade from Khotan to China. Jade pieces from the Tarim Basin have been found in Chinese archaeological sites. Chinese carvers in Xinglongwa and Chahai had been carving ring-shaped pendants "from greenish jade from Khotan as early as 5000 BC".[101] The hundreds of jade pieces found in the tomb of Fuhao from the late Shang dynasty by Zheng Zhenxiang and her team all originated from Khotan.[102] According to the Chinese text Guanzi, the Yuezhi, described in the book as Yuzhi 禺氏, or Niuzhi 牛氏, supplied jade to the Chinese.[103] It would seem, from secondary sources, the prevalence of jade from Khotan in ancient Chinese is due to its quality and the relative lack of such jade elsewhere.

Xuanzang also observed jade on sale in Khotan in 645 and provided a number of examples of the jade trade.[101]

Khotan coinage

editThe Kingdom of Khotan is known to have produced both cash-style coinage and coins without holes[104][105][106]

| Inscription | Traditional Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Approximate years of production | King | Coinage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu Fang | 于方 | yú fāng | 129 - 130 CE | Fang Qian | |

| Zhong Er Shi Si Zhu Tong Qian | 重廿四銖銅錢 | 100 - 200 CE | Maharajasa Yidirajasa Gurgamoasa | ||

| Liu Zhu | 六銖 | 0 - 200 CE | Maharajasa Yidirajasa Gurgamoasa(?) |

Genetics

editHaplogroups

editAt the cemetery in Sampul (Chinese: 山普拉), ~14 km from the archaeological site of Khotan in Lop County,[107] where Hellenistic art such as the Sampul tapestry has been found (its provenance most likely from the nearby Greco-Bactrian Kingdom),[108] the local inhabitants buried their dead there from roughly 217 BC to 283 AD.[109] Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities to peoples from the Caucasus, specifically a maternal lineage linked to Ossetians and Iranians, as well as an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal lineage.[107][110] Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that Alexander the Great, who married a Sogdian woman from Bactria named Roxana,[111][112][113] encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially the later kings of the Seleucid Empire and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom had a mixed Persian-Greek ethnic background.[114][115][116][117]

According to other genetic studies, the Khotanese Sakas had paternal haplogroups Q1a, O3a, O2a, R1a, R1b. Among the maternal haplogroups were H6a, H14b, U3b, U4b, M3, U5b, H, U4a, C4a, W3a, H6a, U5a, H2b, H5c, T1a, J1b, R2, N.[118]

Autosomal DNA

editGenetically, the Khotanese Sakas were of heterogeneous origin, primarily descended from steppe pastoralists associated with the Andronovo/Sintasha and Afanasevo cultures, with significant contributions from Bronze Age populations associated with bmac, Baikal HG, Yellow farmer and local Tarim mummies, and minor contributions from APS and AASI. During the Iron Age, the inhabitants received minor gene flow associated with the Xiongnu.[119]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

editBook references

edit- ^ Stein, M. Aurel (1907). Ancient Khotan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Charles Higham (2004). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 77–81

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road". ChinaKnowledge.de. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ a b H.W. Bailey (31 October 1979). Khotanese Texts (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-04080-8.

- ^ "藏文文献中"李域"(li-yul,于阗)的不同称谓". qkzz.net. Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "神秘消失的古国(十):于阗". 华夏地理互动社区. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008.

- ^ "Section 4 – The Kingdom of Yutian 于寘 (modern Khotan or Hetian)". depts.washington.edu.

- ^ Stein, Aurel. "Memoir on Maps of Chinese Turkistan and Kansu: vol.1".

- ^ Mukerjee 1964.

- ^ Jan Romgard (2008). "Questions of Ancient Human Settlements in Xinjiang and the Early Silk Road Trade, with an Overview of the Silk Road Research Institutions and Scholars in Beijing, Gansu, and Xinjiang" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (185): 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2012.

- ^ Jeong Su-il (17 July 2016). "Jade". The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Seoul Selection. ISBN 978-1-62412-076-3.

- ^ a b Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ Smith, Vincent A. (1999). The Early History of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1.

- ^ a b Xavier Tremblay (11 May 2007). Ann Heirman; Stephan Peter Bumbacher (eds.). The Spread of Buddhism. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ Stein, Aurel. On Ancient Central-Asian Tracks: vol.1. p. 91.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (August 2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ Suzanne G., Valenstein (2007). "Cultural Convergence in the Northern Qi Period: A Flamboyant Chinese Ceramic Container". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 26, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Lucas, Christopoulos (August 2012). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (230): 9–20. ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ For another thorough assessment, see W.W. Tarn (1966), The Greeks in Bactria and India, reprint edition, London & New York: Cambridge University Press, pp 109-111.

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1990). The History and Culture of the Indian People: the age of imperial unity. vol. [2]. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 641.

- ^ Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ Rhie, Marylin Martin (2007), Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 1 Later Han, Three Kingdoms and Western Chin in China and Bactria to Shan-shan in Central Asia, Leiden: Brill. p. 254.

- ^ Xavier Tremblay, "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century," in The Spread of Buddhism, eds Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Sampul (Approved - N) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ^ سامپۇل (Variant Non-Roman Script - VS) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (30 November 2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-78076-060-5.

- ^ Ronald E. Emmerick (13 May 2013). "Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Gernot Windfuhr (ed.). Iranian Languages. Routledge. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- ^ C. Debaine-Francfort; A. Idriss (2001). Keriya, mémoires d'un fleuve. Archéologie et civilations des oasis du Taklamakan. Electricite de France. ISBN 978-2-86805-094-6.

- ^ J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Zhang Guang-da (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: AD 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 978-81-208-1540-7.

- ^ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ^ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- ^ Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp 80-81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- ^ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377-388, 391, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ^ Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp 5-8 ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- ^ Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 174-189, 196-198, 241-242 ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- ^ Yu Taishan (June 2010). "The Earliest Tocharians in China" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers: 21–22.

- ^ Kazuo Enoki (1998), "The So-called Sino-Kharoshthi Coins," in Rokuro Kono (ed.), Studia Asiatica: The Collected Papers in Western Languages of the Late Dr. Kazuo Enoki, Tokyo: Kyu-Shoin, pp. 396–97.

- ^ Bailey, H.W. (1996). "Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1231–1235. ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4.

- ^ Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46.

- ^ Mentioned by the 8th-century Tibetan Buddhist history, The Prophecy of the Li Country. Emmerick, R. E. 1967. Tibetan Texts Concerning Khotan. Oxford University Press, London, p. 47.

- ^ Hulsewé, A F P (1979). China in central Asia : the early stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of The history of the former Han dynasty. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2., p. 97.

- ^ a b Hill 2009, p. 17-19.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 22, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Rafe de Crespigny (14 May 2014). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23-220 AD). Brill Academic Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-474-1184-0.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (28 March 1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-691-02469-1.

- ^ a b c James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Beckwith 1993, p. 171.

- ^ Xin Wen (2023). The King's Road: Diplomacy and the Remaking of the Silk Road. Princeton University Press. pp. 35, 254–255. ISBN 9780691237831.

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 23, 65.

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 327-8.

- ^ Valerie Hansen (17 July 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ George Michell; John Gollings; Marika Vicziany; Yen Hu Tsui (2008). Kashgar: Oasis City on China's Old Silk Road. Frances Lincoln. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-7112-2913-6.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ E. Yarshater, ed. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7, The Iranian Settlements to the East of the Pamirs". The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3). The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012: 632. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. S2CID 162917965.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3). The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012: 633. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. S2CID 162917965.

- ^ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3). The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012: 634. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. S2CID 162917965.

- ^ Matthew Tom Kapstein; Brandon Dotson, eds. (20 July 2007). Contributions to the Cultural History of Early Tibet. Brill. p. 96. ISBN 978-90-04-16064-4.

- ^ a b Valerie Hansen (17 July 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ Takao Moriyasu (2004). Die Geschichte des uigurischen Manichäismus an der Seidenstrasse: Forschungen zu manichäischen Quellen und ihrem geschichtlichen Hintergrund. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05068-5., p 207

- ^ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute., p. 160

- ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

- ^ Anna Akasoy; Charles S. F. Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (2011). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2., p. 35

- ^ http://journals.manas.edu.kg/mjtc/oldarchives/2004/17_781-2049-1-PB.pdf Archived 19 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- ^ J.M. Dent (1908), "Chapter 33: Of the City of Khotan - Which is Supplied with All the Necessaries of Life", The travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, pp. 96–97

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-24340-8.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974). Comprehensive history of Bihar. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute.

- ^ Emmerick, R E (1979). A guide to the literature of Khotan. Reiyukai Library., p.4-5.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 17.

- ^ Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965, pp. 16-20.

- ^ Hill (1988), p. 184.

- ^ Hill (1988), p. 185.

- ^ Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols., p. 180. Clarendon Press. Oxford. [1]

- ^ Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols., p. 183. Clarendon Press. Oxford. [2]

- ^ "Notes on Marco Polo: Vol.1 / Page 435 (Color Image)".

- ^ Ehsan Yar-Shater, William Bayne Fisher, The Cambridge history of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press, 1983, page 963.

- ^ Baij Nath Puri (December 1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 53. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ^ a b Ma Yong; Sun Yutang (1999). Janos Harmatta (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilisations: Vol 2. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-81-208-1408-0.

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. London. p. 95.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). "Khotan", in Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- ^ "Travels of Fa-Hsien -- Buddhist Pilgrim of Fifth Century By Irma Marx". Silkroads foundation. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Ruixuan, Chen. "Buddhism in Khotan". Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism Online. doi:10.1163/2467-9666_enbo_COM_4206.

- ^ Lopez, Donald (2014). "Śikṣānanda". The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1991). "Christianity III. In Central Asia and Chinese Turkestan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. V. pp. 330–34. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Emmerick, R. E. (1992). "Khotanese kīrästānä 'Christian'?". Histoire et cultes de l'Asie centrale préislamique. Colloques internationaux du CNRS. Paris: CNRS Éditions: 279–282. doi:10.3917/cnrs.berna.1992.01. ISBN 978-2-222-04598-4. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^

Guang-Dah, Z. (1996). B. A. Litvinsky (ed.). The City-States of the Tarim Basin (History of Civilisations of Central Asia: Vol III, The Crossroads of Civilisations: A.D.250-750 ed.). Paris. p. 284.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b

Hsüan-Tsang (1985). "Chapter 12". In Ji Xianlin (ed.). Records of the Western Regions. Peking.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Guang-dah, Z. The City-States of the Tarim Basin. p. 285.

- ^ Hill (2009). "Appendix A: Introduction of Silk Cultivation to Khotan in the 1st Century CE", pp. 466-467.

- ^ Boulnois, L (2004). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors and Merchants on the Silk Road. Odyssey. pp. 179.

- ^ Boulnois, L (2004). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors and Merchants on the Silk Road. Odyssey. pp. 179–184.

- ^

Whitfield, Susan (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. London. pp. 24. ISBN 978-0-520-22472-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b

Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road Folio. London. pp. 151.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Liu, Xinru (2001a). "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies". Journal of World History. 12 (2): 261–292. doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0034. JSTOR 20078910. S2CID 162211306.

- ^ "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, ISBN 2-87772-337-2, p. 59.

- ^ "Khotan lead coin". Vladimir Belyaev (Chinese Coinage Web Site). 3 December 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Ancient Khotan" (PDF). by Stein Márk Aurél (hosted on Wikimedia Commons). 1907. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Cribb, Joe, "The Sino-Kharosthi Coins of Khotan: Their Attribution and Relevance to Kushan Chronology: Part 1", Numismatic Chronicle Vol. 144 (1984), pp. 128–152; and Cribb, Joe, "The Sino-Kharosthi Coins of Khotan: Their Attribution and Relevance to Kushan Chronology: Part 2", Numismatic Chronicle Vol. 145 (1985), pp. 136–149.

- ^ a b Chengzhi, Xie; Chunxiang, Li; Yinqiu, Cui; Dawei, Cai; Haijing, Wang; Hong, Zhu; Hui, Zhou (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang". Progress in Natural Science. 17 (8): 927–933. doi:10.1080/10002007088537493.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 15-16, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Livius.org. "Roxane." Articles on Ancient History. Page last modified 17 August 2015. Retrieved on 8 September 2016.

- ^ Strachan, Edward and Roy Bolton (2008), Russia and Europe in the Nineteenth Century, London: Sphinx Fine Art, p. 87, ISBN 978-1-907200-02-1.

- ^ For another publication calling her "Sogdian", see Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 4, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Holt, Frank L. (1989), Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Cologne: E. J. Brill, pp 67–8, ISBN 90-04-08612-9.

- ^ Ahmed, S. Z. (2004), Chaghatai: the Fabulous Cities and People of the Silk Road, West Conshokoken: Infinity Publishing, p. 61.

- ^ Magill, Frank N. et al. (1998), The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 1, Pasadena, Chicago, London,: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, Salem Press, p. 1010, ISBN 0-89356-313-7.

- ^ Lucas Christopoulos writes the following: "The kings (or soldiers) of the Sampul cemetery came from various origins, composing as they did a homogeneous army made of Hellenized Persians, western Scythians, or Sacae Iranians from their mother's side, just as were most of the second generation of Greeks colonists living in the Seleucid Empire. Most of the soldiers of Alexander the Great who stayed in Persia, India and central Asia had married local women, thus their leading generals were mostly Greeks from their father's side or had Greco-Macedonian grandfathers. Antiochos had a Persian mother, and all the later Indo-Greeks or Greco-Bactrians were revered in the population as locals, as they used both Greek and Bactrian scripts on their coins and worshipped the local gods. The DNA testing of the Sampul cemetery shows that the occupants had paternal origins in the eastern part of the Mediterranean"; see Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ^ Kumar, Vikas; Wang, Wenjun; Jie, Zhang; Wang, Yongqiang; Ruan, Qiurong; Yu, Jianjun; Wu, Xiaohong; Hu, Xingjun; Wu, Xinhua; Guo, Wu; Wang, Bo; Niyazi, Alipujiang; Lv, Enguo; Tang, Zihua; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Dai, Qingyan; Yang, Ruowei; Feng, Xiaotian; Ping, Wanjing; Zhang, Lizhao; Zhang, Ming; Hou, Weihong; Yichen, Liu; E. Andrew, Bennett (2022). "Bronze and Iron Age population movements underlie Xinjiang population history". Science. 376 (6588): 62–69. doi:10.1126/science.abm4247. PMID 35357918.

- ^ Kumar, Vikas; Wang, Wenjun; Jie, Zhang; Wang, Yongqiang; Ruan, Qiurong; Yu, Jianjun; Wu, Xiaohong; Hu, Xingjun; Wu, Xinhua; Guo, Wu; Wang, Bo; Niyazi, Alipujiang; Lv, Enguo; Tang, Zihua; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Dai, Qingyan; Yang, Ruowei; Feng, Xiaotian; Ping, Wanjing; Zhang, Lizhao; Zhang, Ming; Hou, Weihong; Yichen, Liu; E. Andrew, Bennett (2022). "Bronze and Iron Age population movements underlie Xinjiang population history". Science. 376 (6588): 62–69. doi:10.1126/science.abm4247. PMID 35357918.

- ^ Nicholson, Oliver (19 April 2018). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 863. ISBN 978-0-19-256246-3.

Khotanese language and literature" entry: "...the Saka kingdom of Khotan..."

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne; Yarshater, Ehsan (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 614. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

One branch of the Sakas who founded a kingdom in Khotan (in the Tarim Basin) were zealous Buddhist....

- ^ Dickens 2018, p. 363.

- ^ Maggi 2021.

- ^ Emmerick & Macuch 2008, p. 330.

- ^ Compareti 2015, p. 199.

- ^ Nicolini-Zani 2022, p. 26 (note 94).

Web-references

edit- ^ "The Sakan Language". The Linguist. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ "Archaeological GIS and Oasis Geography in the Tarim Basin". The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ a b "The Buddhism of Khotan". idp.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

Sources

edit- Histoire de la ville de Khotan: tirée des annales de la chine et traduite du chinois; Suivie de Recherches sur la substance minérale appelée par les Chinois PIERRE DE IU, et sur le Jaspe des anciens. Abel Rémusat. Paris. L'imprimerie de doublet. 1820. Downloadable from: [3]

- Bailey, H. W. (1961). Indo-Scythian Studies being Khotanese Texts. Volume IV. Translated and edited by H. W. Bailey. Indo-Scythian Studies, Cambridge, The University Press. 1961.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

- Beal, Samuel. 1911. The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Emmerick, R. E. 1967. Tibetan Texts Concerning Khotan. Oxford University Press, London.

- Emmerick, R. E. 1979. Guide to the Literature of Khotan. Reiyukai Library, Tokyo.

- Emmerick, Ronald E.; Macuch, Maria (2008). The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran: Companion Volume I. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85772-356-7.

- Compareti, Matteo (2015). "Armenian Pre-Christian Divinities: Some Evidence from the History of Art and Archaeological Investigation". In Asatrian, Garnik (ed.). Studies on Iran and The Caucasus. Brill. pp. 193–205. ISBN 978-90-04-30206-8.

- Dickens, Mark (2018). "Khotanese language and literature". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 863. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Grousset, Rene. 1970. The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Trans. by Naomi Walford. New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9

- Hill, John E. July, 1988. "Notes on the Dating of Khotanese History." Indo-Iranian Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3. See: [4] for paid copy of original version. Updated version of this article is available for free download (with registration) at: [5]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. [6]

- Hill, John E. (2009), Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE, Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1

- Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965.

- Maggi, Mauro (2021). "Khotan v. Khotanese Literature". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Mukerjee, Radhakamal (1964), The flowering of Indian art: the growth and spread of a civilization, Asia Pub. House

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo (2022). The Luminous Way to the East: Texts and History of the First Encounter of Christianity with China. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197609644.

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004252332, ISBN 9789004250420

- Russell-Smith, Lilla (2005), Uygur Patronage in Dunhuang

- Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974), Comprehensive history of Bihar, Volume 1, Deel 2, Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute

- Sims-Williams, Ursula. 'The Kingdom of Khotan to AD 1000: A Meeting of Cultures.' Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 3 (2008).

- Watters, Thomas (1904–1905). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India. London. Royal Asiatic Society. Reprint: 1973.

- Whitfield, Susan. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London. The British Library 2004.

- Williams, Joanna. 'Iconography of Khotanese Painting'. East & West (Rome) XXIII (1973), 109–54.

Further reading

edit- Hill, John E. (2003). Draft version of: "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. 2nd Edition." "Appendix A: The Introduction of Silk Cultivation to Khotan in the 1st Century CE." [7]

- Martini, G. (2011). "Mahāmaitrī in a Mahāyāna Sūtra in Khotanese - Continuity and Innovation in Buddhist Meditation", Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 24: 121–194. ISSN 1017-7132. [8]

- 1904 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan, London, Hurst and Blackett, Ltd. Reprint Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 2000 Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan : vol.1

- 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.M. A. Stein – Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books at dsr.nii.ac.jp</ref> Ancient Khotan : vol.1 Ancient Khotan : vol.2