The Dutch Cape Colony (Dutch: Kaapkolonie) was a Dutch United East India Company (VOC) colony in Southern Africa, centered on the Cape of Good Hope, from where it derived its name. The original colony and the successive states that the colony was incorporated into occupied much of modern South Africa. Between 1652 and 1691, it was a Commandment, and between 1691 and 1795, a Governorate of the VOC. Jan van Riebeeck established the colony as a re-supply and layover port for vessels of the VOC trading with Asia.[2] The Cape came under VOC rule from 1652 to 1795 and from 1803 to 1806 was ruled by the Batavian Republic.[3] Much to the dismay of the shareholders of the VOC, who focused primarily on making profits from the Asian trade, the colony rapidly expanded into a settler colony in the years after its founding.

Dutch Cape Colony Kaapkolonie (Dutch) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1652–1806 | |||||||||||||

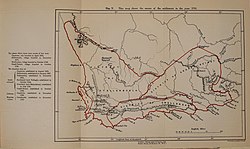

VOC Cape Colony at its largest extent in 1795 | |||||||||||||

| Status | Colony under Company rule (1652–1795) British occupation (1795–1803) Colony of the Batavian Republic (1803–1806) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Castle of Good Hope (1st) Kaapstad (2nd) | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | Dutch Afrikaans | ||||||||||||

Common languages | Early Afrikaans Khoikhoi isiXhosa Malay | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Dutch Reformed native beliefs | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

• 1652–1662 | Jan van Riebeeck | ||||||||||||

• 1662–1666 | Zacharias Wagenaer | ||||||||||||

• 1771–1785 | Joachim van Plettenberg | ||||||||||||

• 1803–1806 | Jan Willem Janssens | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonialism | ||||||||||||

| 6 April 1652 | |||||||||||||

• Elevated to Governorate | 1691 | ||||||||||||

| 7 August 1795 | |||||||||||||

| 1 March 1803 | |||||||||||||

| 8 January 1806 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

• Total | 145,000 km2 (56,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1797[1] | 61,947 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Dutch rijksdaalder | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | South Africa | ||||||||||||

As the only permanent settlement of the Dutch United East India Company not serving as a trading post, it proved an ideal retirement place for employees of the company. After several years of service in the company, an employee could lease a piece of land in the colony as a Vryburgher ('free citizen'), on which he had to cultivate crops that he had to sell to the United East India Company for a fixed price. As these farms were labour-intensive, Vryburghers imported slaves from Madagascar, Mozambique and Asia (Dutch East Indies and Dutch Ceylon), which rapidly increased the number of inhabitants.[2] After King Louis XIV of France issued the Edict of Fontainebleau in October 1685 (revoking the Edict of Nantes of 1598), thereby ending protection of the right of Huguenots in France to practise Protestant worship without persecution from the state, the colony attracted many Huguenot settlers, who eventually mixed with the general Vryburgher population.

Due to the authoritarian rule of the company (telling farmers what to grow for what price, controlling immigration, and monopolising trade), some farmers tried to escape the rule of the company by moving further inland. The company, in an effort to control these migrants, established a magistracy at Swellendam in 1745 and another at Graaff Reinet in 1786, and declared the Gamtoos River as the eastern frontier of the colony, only to see the Trekboers cross it soon afterwards. In order to keep out Cape native pastoralists, organised increasingly under the resisting, rising house of Xhosa, the VOC agreed in 1780 to make the Great Fish River the boundary of the colony.

In 1795, after the Battle of Muizenberg in present-day Cape Town, the British occupied the colony. Under the terms of the Peace of Amiens of 1802, Britain ceded the colony back to the Dutch on 1 March 1803, but as the Batavian Republic had since nationalized the United East India Company (1796), the colony came under the direct rule of The Hague. Dutch control did not last long, however, as the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (18 May 1803) invalidated the Peace of Amiens. In January 1806, the British occupied the colony for a second time after the Battle of Blaauwberg at present-day Bloubergstrand. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 confirmed the transfer of sovereignty to Great Britain.

History

editUnited East India Company

editTraders of the United East India Company (VOC), under the command of Jan van Riebeeck, were the first people to establish a European colony in South Africa. The Cape settlement was built by them in 1652 as a re-supply point and way-station for United East India Company vessels on their way back and forth between the Netherlands and Batavia (Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. The support station gradually became a settler community, the forebears of the Boers, and the Cape Dutch who collectively became modern-day Afrikaners.

Khoi people of the Cape

editAt the time of first European settlement in the Cape, the southwest of Africa was inhabited by Khoikhoi pastoralists and hunters. Disgruntled by the disruption of their seasonal visit to the area for which purpose they grazed their cattle at the foot of Table Mountain only to find European settlers occupying and farming the land, leading to the first Khoi-Dutch War as part of a series of Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars. After the war, the natives ceded the land to the settlers in 1660. During a visit in 1672, the high-ranking Commissioner Arnout van Overbeke made a formal purchase of the Cape territory, although already ceded in 1660, his reason was to "prevent future disputes".[4]

The ability of the European settlers to produce food at the Cape initiated the decline of the nomadic lifestyle of the Khoi and Tuu speaking peoples since food was produced at a fixed location. Thus by 1672, the permanent indigenous residents living at the Cape had grown substantially. The first school to be built in South Africa by the settlers were for the sake of the slaves who had been rescued from a Portuguese slave ship and arrived at the Cape with the Amersfoort in 1658. Later on, the school was also attended by the children of the indigenes and the Free Burghers. The Dutch language was taught at schools as the main medium for commercial purposes, with the result that the indigenous people and even the French settlers found themselves speaking Dutch more than their native languages. The principles of Christianity were also introduced at the school resulting in the baptisms of many slaves and indigenous residents.[4]

Conflicts with the settlers and the effects of smallpox decimated their numbers in 1713 and 1755, until gradually the breakdown of their society led them to be scattered and ethnically cleansed beyond the colonial frontiers: both beyond the Eastward-expanding frontier (to form eventually the future resisting population of the frontier wars), as well as beyond the Northern open frontier war above the Great Escarpment.[5]

Some worked for the colonists, mostly as shepherds and herdsmen.[6]

Free Burghers

editThe VOC favoured the idea of freemen at the Cape and many settlers requested to be discharged in order to become free burghers; as a result, Jan van Riebeeck approved the notion on favorable conditions and earmarked two areas near the Liesbeek River for farming purposes in 1657. The two areas which were allocated to the freemen, for agricultural purposes, were named Groeneveld and Dutch Garden. These areas were separated by the Amstel River (Liesbeek River). Nine of the best applicants were selected to use the land for agricultural purposes. The freemen or free burghers as they were afterwards termed, thus became subjects, and were no longer servants, of the company.[7]

Trekboers

editAfter the first settlers spread out around the Company station, nomadic European livestock farmers, or Trekboeren, moved more widely afield, leaving the richer, but limited, farming lands of the coast for the drier interior tableland. There they contested still wider groups of Khoe-speaking cattle herders for the best grazing lands.

The Cape society in this period was thus a diverse one. The emergence of Afrikaans reflects this diversity, from its roots as a Dutch pidgin, to its subsequent creolisation and use as "Kitchen Dutch" by slaves and serfs of the colonials, and its later use in Cape Islam by them when it first became a written language that used the Arabic letters. By the time of British rule after 1795, the sociopolitical foundations were firmly laid.

British conquest

editIn 1795, France occupied the Dutch Republic. This prompted Great Britain, at war with France, to occupy the territory that same year as a way to better control the seas on the way to India. The British sent a fleet of nine warships which anchored at Simon's Town and, following the defeat of the Dutch militia at the Battle of Muizenberg, took control of the territory. The United East India Company transferred its territories and claims to the Batavian Republic (the Dutch sister republic established by France) in 1798, then ceased to exist in 1799. Improving relations between Britain and Napoleonic France, and its vassal state the Batavian Republic, led the British to hand the Cape Colony over to the Batavian Republic in 1803, under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens.

In 1806, the Cape, now nominally controlled by the Batavian Republic, was occupied again by the British after their victory in the Battle of Blaauwberg. The peace between Britain and Napoleonic France had broken after one year, while Napoleon had been strengthening his influence on the Batavian Republic (which he would replace with a monarchy later that year). The British established their colony to control the Far East trade routes. In 1814 the Dutch government formally ceded sovereignty over the Cape to the British, under the terms of the Convention of London.

Administrative divisions

editThe Dutch Cape Colony was divided into four districts. In 1797 their "recorded" populations were:[8]

| District | Free Christians | Slaves | "Hottentots" | Total (1797) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District of the Cape | 6,261 | 11,891 | - | 18,152 |

| District of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein | 7,256 | 10,703 | 5,000 | 22,959 |

| District of Zwellendam | 3,967 | 2,196 | 500 | 6,663 |

| District of Graaff Reynet | 4,262 | 964 | 8,947 | 14,173 |

Demographics

editDuring this period a significant proportion of marriages were interracial, this is at least partially attributed to a lack of 'White' or 'Christian' women within the colony. What later became the racial division between 'White' and 'non-White' populations originally began as a division between Christian and non-Christian populations.[9] The Geslags-registeers estimated that seven percent of the Afrikaner gene pool in 1807 was non-White.[9]

| Year | White men | White women | White children | White total | Total population | Source/notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1658 | 360 | Recorded population of Cape Town only.[citation needed] | ||||

| 1701 | 418 | 242 | 295 | 1,265 | - | Excluding indentured servants.[9] |

| 1723 | 679 | 433 | 544 | 2,245 | - | Excluding indentured servants.[9] |

| 1753 | 1,478 | 1,026 | 1,396 | 5,419 | - | Excluding indentured servants.[9] |

| 1773 | 2,300 | 1,578 | 2,138 | 8,285 | - | Excluding indentured servants.[9] |

| 1795 | 4,259 | 2,870 | 3,963 | 14,929 | Excluding indentured servants.[9] | |

| 1796 | - | - | - | - | 61,947 | Total for all groups.[10] |

Commanders and Governors of the Cape Colony (1652–1806)

editThe title of the founder of the Cape Colony, Jan van Riebeeck, was installed as "Commander of the Cape", a position he held from 1652 to 1662. During the tenure of Simon van der Stel, the colony was elevated to the rank of a governorate, hence he was promoted to the position of "Governor of the Cape".

| Name | Period | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Jan van Riebeeck | 7 April 1652 – 6 May 1662 | Commander |

| Zacharias Wagenaer | 6 May 1662 – 27 September 1666 | Commander |

| Cornelis van Quaelberg | 27 September 1666 – 18 June 1668 | Commander |

| Jacob Borghorst | 18 June 1668 – 25 March 1670 | Commander |

| Pieter Hackius | 25 March 1670 – 30 November 1671 | Commander and Governor |

| 1671–1672 | Acting Council | |

| Albert van Breugel | April 1672 – 2 October 1672 | Acting Commander |

| Isbrand Goske | 2 October 1672 – 14 March 1676 | Governor |

| Johan Bax van Herenthals | 14 March 1676 – 29 June 1678 | Commander |

| Hendrik Crudop | 29 June 1678 – 12 October 1679 | Acting Commander |

| Simon van der Stel | 10 December 1679 – 1 June 1691 | Commander, after 1691 Governor |

| Name | Period | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Simon van der Stel | 1 June 1691 – 2 November 1699 | Governor |

| Willem Adriaan van der Stel | 2 November 1699 – 3 June 1707 | Governor |

| Johan Cornelis d'Ableing | 3 June 1707 – 1 February 1708 | Acting Governor |

| Louis van Assenburgh | 1 February 1708 – 27 December 1711 | Governor |

| Willem Helot (acting) | 27 December 1711 – 28 March 1714 | Acting Governor |

| Maurits Pasques de Chavonnes | 28 March 1714 – 8 September 1724 | Governor |

| Jan de la Fontaine (acting) | 8 September 1724 – 25 February 1727 | Acting Governor |

| Pieter Gysbert Noodt | 25 February 1727 – 23 April 1729 | Governor |

| Jan de la Fontaine | 23 April 1729 – 8 March 1737 | Acting Governor |

| Jan de la Fontaine | 8 March 1737 – 31 August 1737 | Governor |

| Adriaan van Kervel | 31 August 1737 – 19 September 1737 (died after three weeks in office) | Governor |

| Daniël van den Henghel | 19 September 1737 – 14 April 1739 | Acting Governor |

| Hendrik Swellengrebel | 14 April 1739 – 27 February 1751 | Governor |

| Ryk Tulbagh | 27 February 1751 – 11 August 1771 | Governor |

| Baron Joachim van Plettenberg | 12 August 1771 – 18 May 1774 | Acting Governor |

| Baron Pieter van Reede van Oudtshoorn | 1772 – 23 January 1773 (died at sea on his way to the Cape) | Governor designate |

| Baron Joachim van Plettenberg | 18 May 1774 – 14 February 1785 | Governor |

| Cornelis Jacob van de Graaff | 14 February 1785 – 24 June 1791 | Governor |

| Johan Isaac Rhenius | 24 June 1791 – 3 July 1792 | Acting Governor |

| Sebastiaan Cornelis Nederburgh and Simon Hendrik Frijkenius |

3 July 1792 – 2 September 1793 | Commissioners-General |

| Abraham Josias Sluysken | 2 September 1793 – 16 September 1795 | Commissioner-General |

| Name | Period | Title |

|---|---|---|

| George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney | 1797–1798 | Governor |

| Francis Dundas (1st time) | 1798–1799 | Acting Governor |

| Sir George Yonge | 1799–1801 | Governor |

| Francis Dundas (2nd time) | 1801–1803 | Governor |

| Name | Period | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist | 1803–1804 | Governor |

| Jan Willem Janssens | 1804–1807 | Governor |

References

edit- ^ Robert Montgomery Martin (1836). The British Colonial Library: In 12 volumes. Mortimer. p. 112.

- ^ a b "Kaap de Goede Hoop". De VOC site. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ J. A. Heese, Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner 1657–1867. A. A. Balkema, Kaapstad, 1971. CD Colin Pretorius 2013. ISBN 978-1-920429-13-3. Bladsy 15.

- ^ a b History of South Africa, 1484–1691, G.M. Theal, London 1888

- ^ Penn, Nigel G (1995). "The Northern Cape Frontier Zone 1700- c.1815" (PDF). The Northern Cape Frontier Zone 1700- c.1815.

- ^ Newmark, S. Daniel. The South African Frontier: Economic Influences 1652–1836. Stanford University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-8047-1617-8.

- ^ Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, January 1652 - December 1658, Riebeeck's Journal, H.C.V. Leibrandt, pp. 47–48

- ^ Sir John Barrow (1806). Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa. T. Cadell and W. Davies. p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ross, Robert (1975). "The 'White' Population of South Africa in the Eighteenth Century". Population Studies. 29 (2): 217–230. doi:10.2307/2173508. hdl:1887/4261. ISSN 0032-4728. JSTOR 2173508.

- ^ Martin, Robert Montgomery (1836). The British Colonial Library: In 12 volumes. Mortimer. p. 112.

Sources

edit- The Migrant Farmer in the History of the Cape Colony. P.J. Van Der Merwe, Roger B. Beck. Ohio University Press. 1995. 333 pages. ISBN 0-8214-1090-3.

- History of the Boers in South Africa; Or, the Wanderings and Wars of the Emigrant Farmers from Their Leaving the Cape Colony to the Acknowledgment of Their Independence by Great Britain. George McCall Theal. Greenwood Press. 1970. 392 pages. ISBN 0-8371-1661-9.

- Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750–1870: A Tragedy of Manners. Robert Ross, David Anderson. Cambridge University Press. 1999. 220 pages. ISBN 0-521-62122-4.

External Links

edit- Simon van der Stel's journal and daily record of his journey to Namaqualand with the Dutch East India Company, 1685, from the Library of Trinity College Dublin