The Jakarta Charter (Indonesian: Piagam Jakarta) was a document drawn up by members of the Indonesian Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK) on 22 June 1945 in Jakarta that later formed the basis of the preamble to the Constitution of Indonesia. The document contained the five principles of the Pancasila ideology, but it also included an obligation for Muslims to abide by Shariah law. This obligation, which was also known as the "Seven Words" (tujuh kata), was eventually deleted from the enacted constitution after the Indonesian declaration of independence on 18 August 1945. Following the deletion of the "Seven Words" efforts by Islamic parties continued to seek its inclusion, most notably in 1959, when the 1945 constitution was suspended; in 1968, during the Transition to the New Order; and in 2002, following the end of the New Order and the beginning of the Reformasi era.

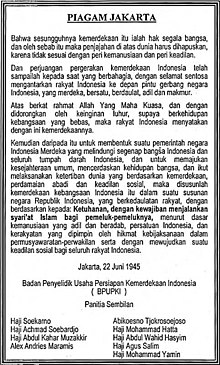

The Jakarta Charter Manuscript written using Improved Spelling system. Sentences containing the famous "seven words" are bolded in this image | |

| Author | Committee of Nine |

|---|---|

| Original title | Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945, Mukadimah |

| Language | Indonesian (Van Ophuijsen Spelling System) |

Publication date | 22 June 1945 |

| Publication place | Indonesia |

| Text | Jakarta Charter at Wikisource |

Background

editFounding of the BPUPK

editPrime Minister of Japan, Kuniaki Koiso, realising Japan was losing the war, promised on 7 September 1944, in a session of the Japanese parliament, that independence for the Dutch East Indies would be achieved "later on".[1] In February 1945, partly in response to the Koiso's declaration, the 16th Army decided to establish a committee to investigate Indonesian independence, known as the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK). This was intended as a concession to Indonesian nationalists, and the Japanese hoped it would redirect nationalist enthusiasm towards harmless arguments between factions. The BPUPK was announced by the Japanese administration on 1 March 1945 to work on "preparations for independence in the region of the government of this island of Java."[2]

First BPUPK session

editThe committee, which was supposed to lay the foundations for the national identity of Indonesia by drafting a constitution, consisted of 62 Indonesian members, 47 of whom belonged to the secular nationalists and 15 to the Islamists.[3] Members of the Islamist camp wanted a new state which was based on sharia law, as opposed to a secular state.[4] From 29 May to 1 June 1945, the BPUPK came to Jakarta for its first conference. At this conference, Sukarno gave his famous speech in which he introduced the principles of the Pancasila.[5]

Committee of Nine

editIn the recess between the two BPUPK sessions, at the urging of future president Sukarno, the delegates set up an eight-person Small Commission (Panitia Kecil), which was headed by Sukarno and had the task of collecting and discussing the proposals submitted by the other delegates.[6] To reduce tensions between the national and Islamic groups, Sukarno formed a Committee of Nine on 18 June 1945. Over the course of the afternoon of 22 June, the nine men produced a preamble for the constitution that included Sukarno's Pancasila philosophy, but added the seven words in Indonesian (dengan kewajiban menjalankan syariat Islam bagi pemeluknya)[7] that placed an obligation on Muslims to abide by Islamic law.[6] Mohammad Yamin, who played a dominant role in the wording, named the preamble the Jakarta Charter.[8] The committee chaired by Sukarno was tasked with formulating the preamble to the Indonesian constitution that was acceptable to both parties. These members, and their affiliations were:[9]

Members

editSecular Muslim nationalists

editMuslim nationalists

editSecular Christian nationalists

editCompromise

editResults of the committee

editThe results of the Committee of Nine were as follows:

- In the Jakarta Charter, the principle of "belief in one god" is used as the first principle, which differs from the formulation of Pancasila which was put forward by Sukarno in his speech on 1 June 1945, "belief in one god" is the fifth principle.[8]

- In the Jakarta Charter, the existence of the phrase "with the obligation to carry out Islamic law for its adherents" (which became known as the "Seven Words"), recognizes Sharia law for Muslims, this greatly differs from the formulation of Pancasila which was put forward by Sukarno in his speech on 1 June 1945. The "Seven Words" itself was considered ambiguous and it is not known whether it imposes the obligation to carry out Islamic law individually or by the government.[10]

Second BPUPK session

editIn accordance with the advice of the Committee of Nine, the BPUPK held its second (and final) session from 10 to 17 July 1945 under Sukarno's leadership. The aim was to discuss issues related to the constitution, including the draft preamble contained in the Jakarta Charter.[11] On the first day, Sukarno reported the things that had been achieved during the discussions during the recess, including the Jakarta Charter. He also reported that the Small Committee had unanimously accepted the Jakarta Charter. According to Sukarno, this charter contained "all the points of thought that filled the chests of most of the members of Dokuritu Zyunbi Tyoosakai [BPUPK]."[12]

On the second day of the trial (July 11), three BPUPK members expressed their rejection of the "Seven Words" (Tujuh Kata) in the Jakarta Charter. Most notably, Johannes Latuharhary, who was a Protestant member from Ambon, disagreed heavily with the "Seven Words." He felt that the seven words in the Jakarta Charter would have a large impact on other religions. He also expressed his concern that the seven words would force the Minangkabau to abandon their customs and also affect land rights based on customary law in Maluku.[13] Two other members who disagreed with the seven words were Wongsonegoro and Hoesein Djajadiningrat. Both were worried that the "Seven Words" would cause fanaticism among Muslims, a worry Wahid Hasyim (another member of the committee), denied.[14]

Preparatory Committee

editProclamation of Independence

editOn 7 August 1945, the Japanese government announced the formation of the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI). Then, on 12 August, Sukarno was appointed as its chairman by the Commander of the Southern Expeditionary Group Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi.[15] Only four of the nine Jakarta Charter signatories were members of the PPKI, namely Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, Achmad Soebardjo, and Wahid Hasyim.[16] Initially PPKI members would gather on 19 August to finalize Indonesia's constitution.[15] However, on August 6 and 9, 1945, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were atomically bombed by the Allies. Then, on August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced that Japan had unconditionally surrendered to the Allies.

Sukarno and Hatta declared Indonesia's independence on 17 August. Then, on the morning of August 18, the PPKI gathered to ratify Indonesia's constitution. During the meeting, Hatta suggested that the seven words in the Preamble and Article 29 be deleted. As Hatta later explained in his book, around the evening of 17 August, a Japanese Navy officer came up to him and conveyed the news that a Christian nationalist group from Eastern Indonesia rejected seven words because they were considered discriminatory against religious minorities, and they even stated that it would be better to establish their own state outside the Republic of Indonesia if the seven words were not repealed.[17]

Erasing of the "Seven Words"

editHatta then explained his proposed changes: the term "God" would be replaced with "the one and only God", while the term "Mukadimah" which came from Arabic was changed to "Preamble". The verse stating that the President of Indonesia must be Muslim was also removed.[18] After this proposal was accepted, PPKI approved the Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia on the same day, and the seven words were officially abolished. Bali representative I Gusti Ketut Pudja also suggested that "Allah" be replaced with "God". His proposal was accepted, but when the official constitution was published, the changes were not made.[19]

It is not known for certain why PPKI agreed to Hatta's proposal without any resistance from the Islamic group.[20] On the one hand, the composition of PPKI members is very different from that of BPUPK: only 12% of PPKI members are from the Islamic group (while in BPUPK there are 24%).[21] Of the nine signatories to the Jakarta Charter, only three attended the meeting on 18 August. The three people were not from the Islamic group; Hasyim who came from Surabaya only arrived in Jakarta on August 19.[22] On the other hand, Indonesia at that time was threatened by the arrival of Allied troops, so that the priority was national defense and efforts to fight for the aspirations of the Islamic group could be postponed until the situation allowed.[23] The decision to remove the seven words disappointed the Islamic group.[24] They felt increasingly dissatisfied after PPKI on 19 August rejected the proposal to establish a Ministry of Religion. Hadikoesoemo expressed his anger at a meeting of the Muhammadiyah Tanwir Council in Yogyakarta a few days after the PPKI session was over. However, along with the arrival of Allied troops, the Islamic group decided to prioritize national unity in order to maintain Indonesian independence.[25]

Subsequent developments

editOn 17 August 1945, Sukarno and Hatta declared Indonesian independence. The following day, the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI), which had been established with Japanese permission on 7 August, was due to meet. Hatta in particular and Sukarno were both worried that the obligation on Muslims would alienate non-Muslims. Before the meeting, Hatta met with Muslim leaders and managed to persuade them to agree to the removal of the seven words "for the sake of national unity".[17] The PPKI then met and elected Sukarno and Hatta president and vice-president respectively.[26] It then discussed the draft constitution, including the preamble. Hatta spoke in favour of removing the seven words, and Balinese delegate I Gusti Ketut Pudja suggested replacing the Arabic word Allah with the Indonesian word for God (Tuhan). This was accepted, but for some reason when the constitution was officially published, this change was not made.[18] Following further discussion, the constitution was approved.[27]

When the 1945 constitution was replaced by the United States of Indonesia Federal Constitution of 1949, and this in turn replaced by the Provisional Constitution of 1950, there were no attempts to include the seven words in the preambles, despite their similarity to 1945 version.[28] However, in 1959, the Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia, which had been set up to produce a permanent constitution, reached deadlock as the Islamist faction wanted a greater role for Islam, but like the other factions, did not have enough support to win the two-thirds majority to push through its proposals. The Islamist faction supported the government's proposal to return to the 1945 Constitution on condition that the obligation on Muslims be re-inserted in the preamble. The nationalist faction voted this down, and in response, the Islamist faction vetoed the reintroduction of the 1945 Constitution. On 9 July 1959, Sukarno issued a decree dissolving the assembly and reinstating the original constitution, but without the seven words the Islamists wanted. To placate them, Sukarno stated that his decree relied on the Jakarta Charter, which had inspired the 1945 Constitution and which was an "inseparable", but was not a legal part of it.[29][30]

There were two further attempts to revive the Jakarta Charter. In the 1968 special session of the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly (MPRS), Parmusi, a new Islamist party, called for it to have legal force, but the proposal was voted down.[31] In 2002, during the MPR session that passed the final amendments to the constitutions, a number of small Islamic parties with the support of Vice-president Hamzah Haz tried again, this time by amending the Article 29 of the constitution to make shariah law obligatory on Muslims, but they were resoundingly defeated.[27][32]

Text of the document

editIndonesian[33][a]

Bahwa sesoenggoehnja kemerdekaan itoe jalah hak segala bangsa, dan oleh sebab itoe maka pendjadjahan diatas doenia haroes dihapoeskan, karena tidak sesoeai dengan peri-kemanoesiaan dan peri-keadilan.

English[34]

As independence is the right of every people, any form of subjugation in this world, being contrary to humanity (prikemanusiaan) and justice (pri-keadilan), must be abolished.

Dan perdjoeangan pergerakan kemerdekaan Indonesia telah sampailah kepada saat jang berbahagia dengan selamat-sentaoesa mengantarkan rakjat Indonesia kedepan pintoe gerbang Negara Indonesia jang merdeka, bersatoe, berdaoelat, adil dan makmoer.

Now the struggle of the Indonesian independence movement has reached the blessed hour which the Indonesian people have safe and sound been led to the portal of the Indonesian state, which is to be independence, united, sovereign, just and prosperous.

Atas berkat Rahmat Allah Jang Maha Koeasa, dan dengan didorongkan oleh keinginan luhur, soepaja berkehidupan kebangsaan jang bebas, maka rakjat Indonesia dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaanja.

By the grace of Almighty God and moved by the highest ideals to lead a free national life, the Indonesian people hereby declare their independence.

Kemoedian dari pada itu untuk membentoek soeatu Pemerintah Negara Indonesia jang melindungi segenap bangsa Indonesia dan seloeroeh toempah-dara Indonesia, dan oentoek memadjoekan kesedjahteraan oemoem, mentjerdaskan kehidoepan bangsa, dan ikoet melaksanakan ketertiban doenia jang berdasarkan kemerdekaan, perdamaian abadi dan keadilan sosial, maka disoesoenlah kemerdekaan kebangsaan Indonesia itoe dalam soeatu hoekoem dasar Negara Indonesia jang terbentuk dalam soeatu soesoenan negara Republik Indonesia, jang berkedaoelatan rakjat, dengan berdasar kepada: ketoehanan, dengan kewadjiban mendjalankan sjari'at Islam bagi pemeloek-pemeloeknja, menoeroet dasar kemanoesiaan jang adil dan beradab, persatoean Indonesia, dan kerakjatan jang dipimpin oleh hikmat kebidjaksanaan dalam permoesjawaratan/perwakilan serta dengan mewoedjoedkan soeatu keadilan sosial bagi seloeroeh rakjat Indonesia.

Further, in order to establish for the Indonesian state a government which will protect the whole Indonesian people and all Indonesian territory and to promote public welfare, to raise the educational level of the people, and to participate in establishing a world order founded on freedom everlasting peace and social justice, national independence is hereby expressed in a Constitution of the Indonesian state which is molded in the form of the Republic of Indonesia, resting upon the people's sovereignty and founded on (the following principles): The Belief in God, with the obligation to carry out the Syariah Islam for its adherents in accordance with the principle of righteous and moral humanitarianism; the unity, and a democracy led by wise policy of the mutual deliberation of a representative body and ensuring social justice for the whole Indonesian people.

Notes

edit- ^ The text uses the Van Ophuijsen Spelling System, instead of the Improved Spelling system.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Elson 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Anderson 2009, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 37.

- ^ Butt & Lindsey 2012, p. 227.

- ^ Anshari 1976, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Elson 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Nasution 1995, p. 460.

- ^ a b Elson 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 38.

- ^ Boland 2013, p. 27.

- ^ Schindehütte 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 115.

- ^ Boland 2013, p. 29.

- ^ a b Elson 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 46.

- ^ a b Elson 2009, p. 120.

- ^ a b Elson 2009, p. 121.

- ^ Elson 2009, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 42.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 65.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Anshari 1976, p. 64.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 126.

- ^ Kahin 1961, p. 127.

- ^ a b Butt & Lindsey 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Elson 2009, p. 130.

- ^ Indrayana 2008, p. 16-17.

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, p. 417.

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, p. 461.

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, p. 551.

- ^ Schindehütte 2006, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Sukarno 1958, p. 11.

References

edit- Anderson, Benedict (2009). Some Aspects of Indonesian Politics Under the Japanese Occupation: 1944-1945. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-602-8397-29-2.

- Anshari, Saifuddin (1976), The Jakarta Charter of June 1945: A history of the gentlemen's agreement between the Islamic and the Secular Nationalists in modern Indonesia, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University

- Boland, B. J. (2013), The Struggle of Islam in Modern Indonesia, Springer Science & Business Media

- Butt, Simon; Lindsey, Tim (2012). The Constitution of Indonesia: A Contextual Analysis. Oxford & Portland, Oregon: Hart Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84113-018-7.

- Elson, R. E. (2009). "Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945" (PDF). Indonesia. 88 (88): 105–130. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Indrayana, Denny (2008). Indonesian Constitutional Reform, 1999-2002: An Evaluation of Constitution-making in Transition. Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kompas. ISBN 978-979-709-394-5.

- Kahin, George McTurnan (1961) [1952]. Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Nasution, Adnan Buyung (1995), Aspirasi Pemerintahan Konstitutional di Indonesia: Studi Sosio-Legal atas Konstituante 1956-1956 (The Aspiration for Constitutional Government in Indonesia: A Socio-Legal Study of the Indonesian Konstituante 1956-1959) (in Indonesian), Jakarta: Pustaka Utama Grafiti, ISBN 979-444-384-0

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2008) [1981]. A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300 (4th ed.). London: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-54685-1.

- Schindehütte, Matti (2006). Zivilreligion als Verantwortung der Gesellschaft – Religion als politischer Faktor innerhalb der Entwicklung der Pancasila Indonesiens. Hamburg: Abera Verlag.

- Sukarno (1958). The Birth of Pantjasila: An Outline of the Five Principles of the Indonesian State. Ministry of Information.

- Tim Penyusun Naskah Komprehensif Proses dan Hasil Perubahan UUD 1945 (2010) [2008], Naskah Komprehensif Perubahan Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945: Latar Belakang, Proses, dan Hasil Pembahasan, 1999-2002. Buku I: Latar Belakang, Proses, dan Hasil Perubahan UUD 1945 (Comprehensive Documentation of the Amendments to the 1945 Indonesian Constitution: Background, Process and Results of Deliberations. Book I: Background, Process and Results of the Amendments) (in Indonesian), Jakarta: Secretariat General, Constitutional Court

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)