You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Conquest of the Desert (Spanish: Conquista del desierto) was an Argentine military campaign directed mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca during the 1870s and 1880s with the intention of establishing dominance over Patagonia, inhabited primarily by indigenous peoples. The Conquest of the Desert extended Argentine territories into Patagonia and ended Chilean expansion in the region.

| Conquest of the Desert | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

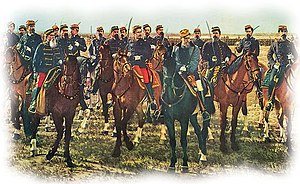

Conquest of the Desert, by Juan Manuel Blanes (fragment showing Julio Argentino Roca, at the front) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Mapuche and Tehuelche allies |

Mapuche tribes | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| Manuel Namuncurá | ||||||||

Argentine troops killed more than 1,000 Mapuches, displaced more than 15,000 more from their traditional lands and enslaved a portion of the remaining indigenous people.[1][2] Settlers of European descent moved in and developed the lands through irrigation for agriculture, converting the territory into an extremely productive area that contributed to the status of Argentina as a great exporter of agricultural products during the early 20th century.[3][4] The conquest was paralleled by a similar campaign in Chile termed the Occupation of Araucanía. The Conquest is controversial: apologists describe it as a civilising mission and as a defense against attacks by the natives, while revisionists label it a genocide.

Background

editThe arrival of the Spanish colonists on the shores of the Río de la Plata and the foundation of the city of Buenos Aires during the 16th century resulted in the first confrontations between the Spanish and the local Indian tribes, mainly the Querandí (also known as the Pampas). Spaniards had purchased the Buenos Aires hinterland from the local Indians to be used for cattle raising. This use displaced most of the animals hunted traditionally by the natives and they struggled to survive. The Indians fought those in the towns, raiding many cattle and horses that altered Native homelands. In retaliation, the Spanish colonists built forts and performed attacks.

As more settlers developed properties, the frontier dividing the colonial farms and the Indian territories gradually moved outwards from Buenos Aires. At the end of the 18th century, the Salado River was the boundary between the civilizations. Due to land loss and environmental devastation caused by cattle, many Indians were forced to abandon their tribes to work on the farms. Some assimilated or intermarried with the caucasian population. The mixed race gauchos developed from those who worked on the ranches.

After Argentina achieved independence in 1816, the provinces had numerous political conflicts. Once these were settled, the government wanted to occupy quickly the lands claimed by the young republic (in part to prevent Chile from enforcing its claim to the same land). It also wanted to increase the national agricultural production and offer new lands to prospective immigrants.

In 1833, Juan Manuel de Rosas in Buenos Aires Province and other military commanders in the Cuyo region coordinated offensives to try to exterminate the resistant indigenous tribes, but only Rosas's expedition achieved some success. By this time Chile had founded Punta Arenas in Magellan Strait in 1845, which threatened the Argentine claims in Patagonia. Later in 1861, Chile began the occupation of Araucanía, which alarmed Argentine authorities because of its rival's growing influence in the zone. Chile had defeated the Mapuche in their central region. This indigenous tribe had strong language and cultural ties to the nomadic tribes on the east side of the Andes, with whom they share the same language.

In 1872, the indigenous commander Calfucurá and his 6,000 warriors attacked the cities of General Alvear, Veinticinco de Mayo and Nueve de Julio. They killed 300 settlers and drove off 200,000 head of cattle. These events were a catalyst for the government to mount the Conquest of the Desert.

The Natives drove the stolen cattle from the raids (malones) to Chile through the Rastrillada de los chilenos and traded them for goods. Historian George V. Rauch notes evidence that Chilean authorities knew about the origin of the cattle and consented to the trading in order to strengthen their influence over Patagonian territories. They expected eventually to occupy those lands in the future.[5]

Alsina's campaign

editIn 1875, Adolfo Alsina, Minister of War for President Nicolás Avellaneda, presented the government with a plan which he later described as having the goal "to populate the desert, and not to destroy the Indians."[6]

The first phase was to connect Buenos Aires and the fortines (fortresses) with telegraph lines. The government signed a peace treaty with chieftain Juan José Catriel. But he violated it a brief time later, as together with chieftain Manuel Namuncurá and 3,500 warriors, he attacked Tres Arroyos, Tandil, Azul, and other towns and farms. The casualties were greater than in 1872: Catriel and Namuncurá's forces killed 400 settlers, captured another 300, and drove off 300,000 head of cattle.[7]

Alsina attacked the Indians, forcing them to retreat, and leaving fortines on his way south to protect the conquered territories. He also constructed the 374 km long trench named the zanja de Alsina ("trench of Alsina"). It was supposed to be a fortified border to the unconquered territories. Three metres wide and two metres deep, it served as an obstacle to cattle drives by the Indians.

The Indians continued taking cattle from farms in the Buenos Aires Province and south of the Mendoza Province, but found it difficult to escape as the animals slowed their march. They had to confront the patrolling units that followed them. As the war continued, some Indians eventually signed peace treaties and settled among the "Christians" behind the lines of forts. Some tribes allied with the Argentine government, being neutral or, less often, fighting for the Argentine Army. In return, they were granted periodical shipments of cattle and food. After Alsina died in 1877, Julio Argentino Roca was appointed Minister of War, and decided to change the strategy.

Roca's campaign

editIn contrast to Alsina, Julio Argentino Roca believed that the only solution against the Indian threat was to extinguish, subdue or expel them.

Our self-respect as a virile people obliges us to put down as soon as possible, by reason or by force, this handful of savages who destroy our wealth and prevent us from definitely occupying, in the name of law, progress and our own security, the richest and most fertile lands of the Republic.

— Julio Argentino Roca, [8]

At the end of 1878 he started the first sweep to "clean" the area between the Alsina trench and the Rio Negro by continuous and systematic attacks on the Indian settlements. On 6 December 1878, elements of the Puán Division commanded by Colonel Teodoro García clashed with a native war party at the Lihué Calel heights. In a brief but intense battle, 50 Indians were killed, 270 captured, and 33 settlers were freed.[9]

Numerous armed encounters would follow, until by December 1878, more than 4,000 Indians had been captured and 400 killed, 150 settlers freed, and 15,000 head of cattle recovered.[9]

With 6,000 soldiers armed with new breech-loading Remington rifles, in 1879 General Roca began the second sweep, reaching Choele Choel in two months, after killing 1,313 Indians and capturing more than 15,000.[3] From other points, southbound companies made their way down to the Rio Negro and the Neuquén River, a northern tributary of the Rio Negro. Together, both rivers marked a frontier from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean.[10] This attack resulted in a large migration of Mapuche into the zone around Curarrehue and Pucón, Chile.

Many European-Argentinian settlements were built in the basin of these two rivers, as well as a number on the Rio Colorado. By sea, some settlements were erected on the southern basin of the Chubut River, mainly by Welsh colonists at y Wladfa.

Final campaign

editRoca was elected and succeeded Nicolás Avellaneda as president. He thought it was imperative to conquer the territory south of the Rio Negro as soon as possible, and ordered a campaign during 1881 commanded by Colonel Conrado Villegas.

Within a year Villegas conquered the Neuquén Province (he reached the Limay River). The campaign continued to push the Indian resistance further south, fighting the last battle on 18 October 1884. The last rebel group, with more than 3,000 warriors commanded by chieftains Inacayal and Foyel, surrendered two months later in present Chubut Province.

During the 1880s the Argentine advances effectively disrupted Chileans and German Chilean trade with indigenous communities east of the Andes. This meant the leather merchants in Southern Chile had to cross the Andes and establish livestock operations. As a result, a number of Chilean-owned companies were established in Argentina. They imported workers from Chile, mostly people from the Chiloé Archipelago.[11] It was in this context that German Chilean Carlos Weiderhold established the trading post and shop La Alemana in 1895, from which the city of Bariloche developed.[11]

Border clashes

editTo counteract the Argentine conquest of Patagonia, the Chileans supplied arms, ammunition and horses to their Indian allies the Mapuches.[12] On 16 January 1883, a 10-man section of a platoon of the Argentine Army in pursuit of a large Indian war party, ran into an ambush in the Pulmarí Valley set by Chilean soldiers. In the engagement that followed, Argentine Captain Emilio Crouzeilles, along with Lieutenant Nicolas Lazcano and several privates, were killed.[13]

On 17 February 1883, Lieutenant-Colonel Juan Díaz, commanding a 16-man Argentine infantry detachment, was trailing a war party of 100 to 150 Indians. Upon reaching Pulmarí Valley, they were surrounded by the Indians and about 50 Chilean soldiers. Much outnumbered, the Argentine soldiers skillfully outfought their attackers, including a bayonet charge mounted by the Chilean detachment.[14] On 21 February 1883, according to Argentine Army Major Manuel Prado, 150-200 Indians armed with Winchesters and Martini–Henry rifles attacked an Argentine Army detachment operating on the Argentine-Chilean border. In a four-hour engagement, 22 Argentine soldiers were killed or wounded at a cost of some 100 warriors.[citation needed]

Historical controversy

editLiterary scholar Jens Andermann has noted that contemporary sources on the campaign conclude that the Conquest was intended by the Argentine government to exterminate the indigenous tribes, and can be classified as genocide.[15] First-hand accounts state that Argentine troops killed prisoners and committed "mass executions".[15] The 15,000 Natives taken captive "became servants or prisoners and were prevented from having children."[3][4] The Argentine Republic in Patagonia "for the colonisation of the bottom of the country, a raid was made against these poor harmless children of nature, and many tribes were wiped out of existence. The Argentines let loose the dogs of war against them; many were killed and the rest – men, women and children – were deported by sea".[16]

Apologists perceive the campaign as intending to conquer specifically those Indigenous groups who refused to submit to Argentine law and frequently performed brutal attacks on frontier civilian settlements.[17] In these attacks, the Natives stole many horses and cattle, killed settlers defending their livestock, and captured women and children to become slaves and/or forced brides of Indian warriors.[18][19]

The Guardian alleged in 2011 that two education officials lost their jobs due to the controversy concerning the Conquest of the Desert: It reported that Juan José Cresto was forced to resign as a director of the Argentine National Historical Museum because he "said the Indians were violent parasites who attacked farms and kidnapped women"[4] and Beatriz Horn, a history teacher in La Pampa Province, was dismissed for "telling a radio station that Roca deserved praise for putting Indians to flight and opening Argentina's frontier to European settlers".[4] Argentine news sources, however, report Juan José Cresto lost his job for being abusive and violent towards employees[20] and Beatriz Horn was dismissed due primarily to her praise for the military dictator Leopoldo Galtieri.[21]

During recent years, Mapuche activist groups and other activist organizations have criticised the representation of Roca in official state imagery. A statue of Roca in the civic center of Bariloche is a frequent site for protests and graffiti by local Amerindian activist organizations.[22][23][24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Mano a mano con Bayer: "Roca restableció la esclavitud en el país"". Diario Jornada. 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24.

- ^ Félix Luna (1989). Soy Roca.

- ^ a b c The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute With Chile, 1870-1902, George V. Rauch, p. 47, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999

- ^ a b c d Carroll, Rory (13 January 2011). "Argentinian founding father recast as genocidal murderer". The Guardian.

- ^ Rauch (1999), The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute, p. 43

- ^ "Reseña sobre la historia de Neuquén" Archived 2006-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, Government of the Neuquén Province (in Spanish)

- ^ Rauch (1999), The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute, p. 42

- ^ Quoted from: Kenneth M. Roth. Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide. University of California Press, 2002. Page 45.

- ^ a b The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute With Chile, 1870-1902, George V. Rauch, p. 45, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999

- ^ "Poblamiento Pampeano" Archived 2005-12-27 at the Wayback Machine – Ministry of Culture of the la Pampa Province (in Spanish)

- ^ a b Muñoz Sougarret, Jorge (2014). "Relaciones de dependencia entre trabajadores y empresas chilenas situadas en el extranjero. San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)" [Dependence Relationships between Workers and Chilean Companies located abroad. San Car-los de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)]. Trashumante: Revista Americana de Historia Social (in Spanish). 3: 74–95. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ 5th Infantry Brigade in the Falklands 1982, Nicholas Van der Bijl, David Aldea, p.29, Leo Cooper, 2003

- ^ Historia de las misiones salesianas en La Pampa, República Argentina, Volume 1, Lorenzo Massa, p. 169, Editorial Don Bosco, 1967

- ^ The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute With Chile, 1870-1902, George V. Rauch, p. 49, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999

- ^ a b Andermann, Jens. Argentine Literature and the 'Conquest of the Desert', 1872-1896, Birkbeck, University of London. Quote: "It is this sudden acceleration, this abrupt change from the discourse of 'defensive warfare' and 'merciful civilization' to that of 'offensive warfare' and of genocide, which is perhaps the most distinctive mark of the literature of the Argentine frontier."

- ^ Canclini, Arnoldo (1980). Congresso nacional de Historia sobre la Conquista del desierto (in Spanish). Academia Nacional de la Historia (Argentina). p. 95.

"para la colonización el fondo del país, se hizo un raid contra estos pobres inofensivos hijos de la naturaleza y muchas tribus fueron borradas de la existencia. Los argentinos dejaron sueltos los perros de la guerra contra ellos; muchos fueron muertos y el resto – hombres, mujeres y niños – fueron deportados por mar"

- ^ Rock, David. State Building and Political Movements in Argentina, 1860-1916. Stanford University Press, 2002, pp. 93-94

- ^ Argentina: Countries of the World, Erika Wittekind, p. 67, ABDO, 01/09/2011

- ^ Captive Women: Oblivion And Memory In Argentina, Susana Rotker, p. 32, University of Minnesota Press, 2002

- ^ "Museo Histórico: hay polémica por el regreso del ex director". www.clarin.com. 25 March 2002.

- ^ Gaceta, La. "Actualidad nacional". www.lagaceta.com.ar.

- ^ "En Bariloche buscan que se retire el monumento a Roca". Diario Río Negro (in European Spanish). 2004-10-13. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ "Pueblo Mapuche - Bs As: Quieren sacar el monumento a Roca". Barilochense.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ "Protesta mapuche: cubren con un "kultrún" la estatua de Roca en Bariloche". www.clarin.com (in Spanish). 12 October 2017. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

Further reading

edit- "Nicolás Avellaneda", biography by Felipe Pigna (in Spanish)

- "Economical consequences of the Conquest of the Desert" - Universidad del CEMA (in Spanish)

- "Effective occupation of the Patagonic region by the Argentine government" - Universidad del CEMA (in Spanish)

- "Campaña del Desierto" - Olimpiadas Nacionales de Contenidos Educativos en Internet (in Spanish)

- "La Guerra del Desierto", different views by Juan José Cresto, Osvaldo Bayer and others - ElOrtiba.org (in Spanish)

- Hasbrouck, Alfred. The Conquest of the DesertThe Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 15, No. 2 (May, 1935), pp. 195–228

- Larson, Carolyne R. (ed). The Conquest of the Desert: Argentina's Indigenous Peoples and the Battle for History (University of New Mexico Press, 2020).

- Commandante Manuel Prado: La guerra al Malón 1907

- New edition: Manuel Prado: La guerra al Malón (The War against the Indians), Editorial Claridad SA, Buenos Aires ISBN 978-950-620-206-4

- Staff, Conquest-of-the-Desert and effect on colonization in Patagonia Encyclopædia Britannica