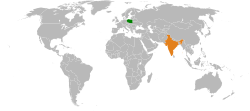

Indo–Polish relations are the bilateral relations between the Republic of Poland and the Republic of India. Historically, relations have generally been friendly, characterised by understanding and cooperation on an international front.

| |

Poland |

India |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of the Republic of Poland, New Delhi | Embassy of India, Warsaw |

| Envoy | |

| Chargé d’affaires Sebastian Domżalski | Ambassador Nagma Mallick |

History

editThe Age of Discovery

editDuring the 16th century Renaissance and the Age of Discovery period in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, a small number of Poland's nobility, statesmen, merchants and writers visited India and fostered the abiding interest of the Polish people in the civilization, philosophy, spiritual traditions, art and culture of India.[1][2] One of the first diplomatic dignitaries and travellers during this period to make Polish contact with India—then under the rule of the Mughal Empire, was the Polish nobleman and statesman Paweł Palczowski who was a long serving royal courtier to King Sigismund III Vasa and from the distinguished senior noble Saszowski family.[1][2][3][4] Others from this period include Erazm Kretkowski a Polish diplomatic representative for King Sigismund II Augustus in the Ottoman Empire in 1538 and royal castellan of Brześć Kujawski and Gniezno, and Krzysztof Pawłowski a Polish seafarer and diarist who provided a description of India preserved in Polish, recorded in a letter dated 1569 to an unknown person;[1][2] Pawłowski who came to India in 1569, left a rudimentary description of the sea route from Gdańsk via Portugal (Lisbon) to India (Goa) in the form of a comprehensive letter-relation to a friend in Kraków, in which described the customs of 'dark' people. A consequence of these voyages soon provided Indian echoes in Polish literature.[1]

As early as 1611, the Polish Catholic priest, translator and poet, Stanislaw Grochowski (1542-1612), published a book titled Cudowne wiersze z indyjskiego jezyka (Wonderful Verses from the Indian Language).[1] It was a translation of the Bhagavad Gita, which had first been translated from Sanskrit into Medieval Latin by the Italian poet and Jesuit missionary Francisco Benci (1542-1594), who had stayed in India and later lectured at the Jesuit college in Pułtusk, Poland, where Stanislaw Grochowski was a professor.[1]

19th and early 20th centuries

editDuring the 19th century, several Sanskrit classics were translated into Polish and a 'History of Ancient India' in Polish was one of the first of its kind to be published in Europe.[1] A Chair of Sanskrit was set up at the Jagiellonian University of Kraków in 1893. Studies and research in Indian languages and literature had developed at the Universities of Kraków, Warsaw, Wrocław and Poznań.

A consulate of Poland in Mumbai, an honorary consulate in Kolkata and a consular agency in Amritsar were established in 1933, 1935 and 1936, respectively, and the consulate in Mumbai was elevated to a consulate-general in 1939.[5]

World War II

editMahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru were known to be vocal supporters of Poland's struggle against the Invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the beginning of World War II.[6][7][8] Both Indian intelligentsia and Indian military officials were vocal supporters of Polish autonomy and freedom when Germany and the Soviet Union occupied Poland in September 1939. Many Polish citizens were given refuge in India by Indian maharajas.[6][9][10] One of the refugees was the accomplished Polish visual artist Stefan Norblin whom the Maharaja of Jodhpur commissioned to decorate the Umaid Bhawan Palace with a series of paintings, decorations and furniture designs. They were rediscovered in the 1990s.[6][11] Whilst staying in India during World War II, Norblin also painted portraits of the local aristocracy and decorated their residences.[11]

Indian prisoners of war were held by the Germans alike Polish and other Allied POWs in the Stalag XX-B and Stalag XXI-B POW camps located in Malbork and Tur, respectively.[12][13]

Poles and Indians were part of the large Allied coalition in the major battles of Tobruk (1941) and Monte Cassino (1944).[14][15]

Aid to Polish refugees in India

editDuring the Second World War Occupation of Poland by the Soviet Union in the east and the German Reich in the west, the Maharaja Jam Sahib of Nawanagar State, Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji Jadeja of Nawanagar, extended hospitality and sanctuary to more than 640 Polish displaced persons, the majority were orphaned children and women, out of some 5,000 refugees sent to India from Soviet deportation, and despite India itself suffering from a severe backdrop of drought and famine at that time.[16][17][18] After their ship and plight was turned away by every country approached and when the British Crown governor in Mumbai (Bombay) too refused them entry, the Maharaja Jam Sahib, frustrated by the lack of empathy and unwillingness of the British government to act, ordered the ship to dock at Rozi port in his province.[16][17] The displaced persons, lived in camps in several places in western India, including Balachadi (near Jamnagar), Valivade (near Kolhapur) and Panchgani.[16][17] Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji's unparalleled act of generosity, saw him become patron of the first public school complex founded in Poland after the Second World War, located in the capital of Warsaw, and named Jam Saheba Digvijay Sinhji in his honour.[16][17][19] In 2012, the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, honoured the 50th anniversary of his death, posthumously awarding the Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, and the Warsaw City Council named one of its city park squares in Ochota district after him - the 'Square of the Good Maharaja' (Skwer Dobrego Maharadży).[18][20]

Cold War

editDuring the post-war period, when Poland became the Polish People's Republic under the Soviet Occupation Forces and Soviet-backed communist regime, Poland, then a state in the Eastern Bloc, was not a free agent to choose its destiny.[9] This relaxed after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. The international situation became less tense, and the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev took a liking to India's prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru.[9] In 1954, Poland and India formally agreed to establish resident diplomatic missions, and the Indian Embassy in Warsaw was opened in 1957, shortly after the 1956 Polish October revolution that marked a change in the politics of Poland.[9] During the Cold War period, both Warsaw and New Delhi had close ties with the Soviet Union and this made them natural friends. On 25 January 1977 an agreement on the operation of air services between the two countries was signed in New Delhi.[21]

One of the political emigrants who avoided returning to communist Poland was the renowned architect Maciej Nowicki. While he was a professor at the University of North Carolina, he was entrusted with designing the modern capital of Punjab. His plans were groundbreaking and could constitute a new quality in world urban planning. However, his project was never realized due to his untimely death in a plane crash on his way back from India to the United States on 31 August 1950. Nowicki was only 40 at the time. The work on the plan of Chandigarh was consequently entrusted to the world-renowned Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier.[22]

Post Cold War

editFollowing the fall of Communism in Poland, both countries focused on improving ties with the European Community and the United States. Even after the events of 1989, when Poland transitioned to the modern democratic Republic of Poland, relations with India have maintained continuity and have remained on an even keel reflecting relations with India were not an adjunct of the Cold War and are based on sound principles. Contacts between the Indian and Polish Parliaments were established after the collapse of Communism in 1989. A Polish parliamentary delegation led by the Marshal of the Sejm, had visited India in December 1992. A Polish-Indian Parliamentary Group had been set up during the term of the last Parliament which held office from 1996 to 2001. Speaker of Lok Sabha, Manohar Joshi led a multi-party Parliamentary delegation to Poland from 22 to 26 May 2002. Also, the Speaker of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, Jozef Oleksy, led a Polish parliamentary delegation to India from 9–11 December 2004. In April 2009, Indian President Pratibha Devisingh Patil visited Poland.[6] In September 2010, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk visited India and met with Indian politicians and businessmen.

In May 2021, Poland donated over 1.5 tons of medical equipment including oxygen concentrators to India in response to a sharp rise of COVID-19 infections in India.[23]

On 22 August 2024, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid an official state visit to Warsaw, Poland. The visit was described as "historic" as it marked the first time in 45 years since the last state visit by an Indian PM to Poland. The Indian PM held talks with the Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, which focused on deepening the bilateral political, economic and security ties between the two countries.[24] During the meeting, the leaders took the decision to elevate the Polish-Indian relations to the level of a "strategic partnership".[25] The talks also included strengthening the defence industry collaboration between India and Poland as well as discussing the ongoing War in Ukraine.[26]

Trade, investment, defence and the economy

editEconomic ties

editBilateral trade between the two countries has grown about eleven times from 1992 to 2008.[6] Bilateral trade, which totaled US$675.73 million (approximately ₹3,825 crores) and US$861.78 million (approximately ₹4,873 crores) in 2006 and 2007 respectively, crossed US$1 billion (approximately ₹5,700 crores) in 2008 with US$1274.77 million[6] (approximately ₹7,000 crores). During 2005, major Indian companies signed several agreements on investments that are expected to create more than 3,500 new jobs in Poland.[27] India's major exports to Poland include Tea, Coffee, Spices, Textiles, Pharmaceuticals, machinery and instruments, auto parts and surgical items. India's imports from Poland include machinery except electric and electronic appliances, artificial resins, plastic material, non-ferrous metals and machine tools.[28] Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) has sent several delegations to Poland to explore economic opportunities in various sectors.[28] Indian companies such as Tata Consultancy Services, Wipro Technologies, ZenSar and Videocon have already set up their bases in Poland.[29] The 'Indo-Polish Chamber of Commerce and Industry'(IPCCI) was formed in 2008 under the astute leadership of Mr Jowahar Jyothi Singh(JJ Singh) to protect and represent the interests within the range of economic activity and to promote economic relations between India and Poland.[29] Direct nonstop flights provided by LOT Polish Airlines between Warsaw Chopin Airport and Indira Gandhi International Airport started September 12, 2019.[30]

Both countries have a long-standing history of cooperation in science and technology. The first Indo-Polish Agreement on this cooperation was signed in March 1974; subsequently, a new agreement with more focus Programmes of Cooperation (POC) in science and technology were signed between the two countries from time to time. The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and the Indian National Science Academy (INSA) have ongoing scientific exchange programs with the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAS).[6]

Defence ties

editIndia's defence relations with Poland have grown from military cooperation to comprehensive defence cooperation that includes courses, training for UN peacekeeping operations, and exchange of observers during army exercises.[31] India and Poland signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Defence Cooperation in February 2003 during the visit of the Prime Minister of Poland Leszek Miller to India. India awarded contracts worth US$600 million (₹3.5 thousand-crores) to Poland for modernisation of tanks and the acquisition of air defence missiles. The T-72M1 with 800 horsepower engines were upgraded with 1000 hp engines and re-equipped with modern fire control systems (DRAWA-T) and thermal imaging equipment. Both India and Poland are considering privatising their defence industries and see good prospects for mutual investments.[32] Indian Army chief General Deepak Kapoor visited Warsaw in March 2008 followed by Poland's Deputy Foreign Minister Ryszard Schnepf in June the same year.[33] India also acquired 625 assault parachutes from the Polish company Air-Pol with automatic devices ensuring their reliable opening, with a total value of US$1.5 million. India's growing defence buy-outs from Poland has disappointed Russia which had considered India a safe market for its military hardware.[34] Poland also delivered a batch of 80 WZT-3 armoured recovery vehicles (ARVs) to the Indian Army in 2001 at the Kolar Gold Fields facility in Karnataka and the remaining batch in 2004. The final batch of 40 WZT-3 ARVs were assembled in India from kits supplied from Poland.[35]

Resident diplomatic missions

edit- India has an embassy in Warsaw.

- Poland has an embassy in New Delhi and a consulate-general in Mumbai.

-

Embassy of India in Warsaw

-

Embassy of Poland in New Delhi

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Pollet, Gilbert (1995). Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact : Proceedings of the 8th International Rāmāyaạ Conference, Leuven, 6-8 July 1991. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. p. 89. ISBN 9789068317015.

- ^ a b c Balcerowicz, Piotr (2011). Art, Myths and Visual Culture of South Asia (PDF). Vol. 4. New Delhi: Monohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9788173049514.

- ^ Okolski, Szymon (1641–1645). "Orbis Polonus splendoribus coeli, triumphis mundi, pulchritudine animantium condecoratus, in quo antiqua Sarmatorum gentiliata pervetusta nobilitatis insignia etc. specificantur et relucent" [Polish Encyclopedia of the ancient Sarmatian families, the history of the coats of arms of the nobles of Poland old and new, their origin as awards for honorable deeds & the arms themselves specifically described and emblazoned]. Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Bj St. Dr. 589099 I (in Latin). III. Kraków: In Officina Typographica Francisci Cæsarii: 94–98.

- ^ Paprocki, Bartłomiej (1584). "Herby Rycerztwa Polskiego" [Coats of Arms of Polish Knights]. Sygnatura Oryginału: Xvi.f.4132 (in Polish and Latin). Kraków: Maciej Garwolczyk: 557–558.

- ^ Ceranka, Paweł; Szczepanik, Krzysztof (2020). Urzędy konsularne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1918–1945. Informator archiwalny (in Polish). Warszawa: Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych, Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych. pp. 36, 72, 173. ISBN 978-83-65681-93-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Indo-Polish relations". Embassy of India in Poland. Archived from the original on 2003-10-31. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Jacobs, Harrison (2 April 2015). "Gandhi's 1940 letter to Adolf Hitler: Seek peace or someone will 'beat you with your own weapon'". New York: Business Insider UK.

- ^ "Letters of note: Mohandas Gandhi's letter to Adolf Hitler, 1939. India's figurehead for independence and non-violent protest pleads with the leader of Nazi Germany". London: The Observer. 12 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bhutani, Surender (14 March 2018). "60 Years of Indo-Polish Relations: A Personal Reflection". Warsaw: Indo Polish Chamber of Commerce and Industry (IPCCI). Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "India and Poland: India-Poland Relations". Warsaw: Embassy of India in Poland & Lithuania. 3 April 2017.

- ^ a b Kępa, Marek (November 2012). "Stefan Norblin's Indian Inspirations — Image Gallery". Warsaw: Culture.pl - Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

- ^ Daniluk, Jan. "Stalag XX B Marienburg: geneza i znaczenie obozu jenieckiego w Malborku-Wielbarku w latach II wojny światowej". In Grudziecka, Beata (ed.). Stalag XX B: historia nieopowiedziana (in Polish). Malbork: Muzeum Miasta Malborka. p. 13. ISBN 978-83-950992-2-9.

- ^ Daniluk, Jan; Winiecki, Mariusz (2020). Stalag XXI B/H Thure. Jeńcy wojenni w Turze w latach II wojny światowej (in Polish and English). Translated by Parsons, Alan. Szubin: Polsko-Amerykańska Fundacja Upamiętnienia Obozów Jenieckich w Szubinie. pp. 20, 54. ISBN 978-83-958269-0-0.

- ^ "The Allied Armies in the Siege of Tobruk, 1941". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Polish Victory. Monte Cassino May 11–19, 1944. Warsaw: Wojskowy Instytut Wydawniczy. 2022. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Jumde, Anandita (17 April 2016). "How One Maharaja Helped Save the Lives of 640 Polish Children and Women During World War II". Bangalore: The Better India, Vikara Media Pvt Ltd.

- ^ a b c d Wójcicka, Ewa. "Google Arts & Culture: 1939-1948 Passage to India, Polish settlements in Balachadi and Valivade". Warsaw: Polish History Museum.

- ^ a b Kowalska, Karolina (30 May 2016). "The Sejm commemorates the "Good Maharaja"". Warsaw: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Wójcicka, Ewa. "International Baccalaureate Organization: Jam Saheba Digvijay Sinhji". Geneva: IB Foundation, Geneva.

- ^ "Good Maharaja Sq opened in Warsaw". Warsaw: Radio Poland. 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Indo-Polish Agreement on Air Services" (PDF). Foreign Affairs Record. XXIII (1): 2. January 1977. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Maciej Nowicki: A Passage to India » Krakow Post". 2012-06-14. Archived from the original on 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ^ "Polska dostarczy do Indii ponad 1,5 tony sprzętu medycznego". Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (in Polish). 7 May 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Vikas Pandey (23 August 2024). "Diplomatic tightrope for Modi as he visits Kyiv after Moscow". bbc.com. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "India-Poland Joint Statement "Establishment of Strategic Partnership"". pmindia.gov.in. 22 August 2024. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "As Modi visits Poland, PM Tusk eyes stronger defence industry ties with India". channelnewsasia.com. 22 August 2024. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Chatterjee, Surojit (18 May 2006). "India, Poland to boost economic ties". IBTimes India. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ a b "POLISH ECONOMY-Foreign Trade". Confedaration of Indian Industry. Retrieved 2008-11-04.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Polish companies seek closer ties with India". IANS. Economic Times. 26 May 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-06-30. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Poland invites Indian investments with focus on SME sector". Business Daily from THE HINDU. January 15, 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-01-31. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Indian Army chief to visit Poland, Belarus". NERVE. 7 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ Raja Mohan, Chilamkuri (Mar 20, 2004). "India, Poland deepen defence ties". The Hindu. Archived from the original on April 13, 2004. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ "India, Poland defence ties strengthening: Raju". Economics times of India. 16 Jun 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ "Polish military monthly reports on Defexpo". Bharat Rakshak. 20 March 2002. Archived from the original on December 6, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ "Indo-Polish Military Ties On The Upswing". Financial Express. May 19, 2003. Retrieved 2008-10-11.