This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The Darmstadt Artists' Colony refers both to a group of Jugendstil artists as well as to the buildings in Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt in which these artists lived and worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The artists were largely financed by patrons and worked together with other members of the group who ideally had concordant artistic tastes.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt | |

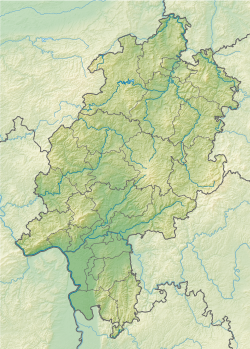

| Location | Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany |

| Criteria | Cultural: |

| Reference | 1614 |

| Inscription | 2021 (44th Session) |

| Area | 7.35 ha (18.2 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 76.54 ha (189.1 acres) |

| Website | www.mathildenhoehe-darmstadt.de |

| Coordinates | 49°52′32″N 8°39′59″E / 49.875433345°N 8.66650397°E |

UNESCO recognized the Mathildenhöhe artists' colony in Darmstadt as a World Heritage Site in 2021, because of its testimony to early modern architecture and landscape design, and its influence in the reform movements of the early 20th century.[1][2][3][4]

Founding

editThe artists' colony was founded in 1899 by Ernest Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse.[5] His motto was: "Mein Hessenland blühe und in ihm die Kunst" ("My Hessian land shall flourish and in it, the art"),[6] and he expected the combination of art and trade to provide economic impulses for his land.[7] The artists' goal was to be the development of modern and forward-looking forms of construction and living. To this end, Ernst Ludwig brought together several artists of the Art Nouveau in Darmstadt: Peter Behrens, Paul Bürck, Rudolf Bosselt, Hans Christiansen, Ludwig Habich, Patriz Huber and Joseph Maria Olbrich.

First Exhibition 1901

editThe first exhibition of the artists' colony took place in 1901 with the title "A Document of German Art".[8] The exhibits were the colony's individual houses, the studios and various temporary constructions. The exhibition was opened on 15 May with a festival proposed by Peter Behrens and inspired interest far beyond Darmstadt's borders, but ended nonetheless with a large financial loss in October. Paul Bürck, Hans Christiansen and Patriz Huber left the colony shortly afterwards, as did Peter Behrens and Rudolf Bosselt in the following years.

Ernst Ludwig House

editThe Ernst Ludwig House was built as a common atelier following plans drawn up by Joseph Maria Olbrich.[9] Olbrich had worked as an architect and was the central figure in the group of artists, Peter Behrens having been involved at first only as a painter and an illustrator. The laying of the foundation stone took place on 24 March 1900. The atelier was both a worksite and a venue for gatherings in the artists' colony. In the middle of the main floor is the meeting room with paintings by Paul Bürck and there are three artist studios on each side of it. There are two underground artists' apartments and underground rooms for business purposes. The entrance is located in a niche that is decorated with gold-plated flower motifs. Two six-metre tall statues, "Man and Woman" or "Strength and Beauty", flank the entrance and are the work of Ludwig Habich. The artists' houses were grouped around the atelier. Towards the end of the 1980s, the building was rebuilt and turned into a museum (Museum Künstlerkolonie Darmstadt) about the Darmstadt Artists' Colony.[10]

The artists' houses

editThe artists could buy property in favourable conditions and construct residential houses that were to feature in the exhibition. It was envisaged that the efforts to combine architecture, interior design, handicraft and painting should thus be demonstrated with concrete examples. Only Olbrich, Christiansen, Habich and Behrens could afford to build homes of their own but there were nonetheless eight fully furnished houses in the first exhibition.

Wilhelm Deiters' House

editWilhelm Deiters was the manager of the artists' colony. His house was designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, who was also responsible for the ground floor interior.[11] It is the smallest of the houses and its particular form is the result of the quadratic shape of the property on which it is built, which lies at the intersection of two streets. It survived the war unscathed and was restored to its original appearance in 1991–1992 following several less fortunate attempts to renovate and redesign it.[12] The building was the home of the German Polish Institute from 1996 to 2016.[13]

The large Glückert House

editJoseph Maria Olbrich also designed this house for Julius Glückert.[14] It was the largest in the exhibition. Julius Glückert was a producer of furniture and an important promoter of the artists' colony. He had envisaged selling the house as soon as it was finished, but decided shortly before its completion to use the building for a permanent exhibition of pieces produced in his factory. The house was partially destroyed in World War II, later rebuilt and then restored in the 1980s. Today it is used by the German Academy for Language and Poetry.[15]

The small Glückert House (Rudolf Bosselt House)

editThis house was also designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich. The sculptures on the facade are the work of Rudolf Bosselt. Patriz Huber was responsible for the interior design. Bosselt began work on the house, but was not able to cover the costs of construction. Glückert thus took over the house and paid for its completion. Its present appearance approximates its original form.

Peter Behrens' House

editPeter Behrens was a self-taught architect.[16] His design for his own house and its interior represented his debut. Having one and the same architect and interior designer gave the house a particularly pronounced consistency. It was however also the single most expensive house in the exhibition, with total costs of 200,000 Mark. Behrens never lived in it, choosing instead to sell it shortly after the exhibition. It was heavily damaged in World War II, but at least the exterior has been largely restored to its original state. Some articles and pieces of furniture were apparently removed from the house at an earlier date and have thus survived.

Joseph Maria Olbrich's House

editOlbrich's own house was relatively cheap at 75,000 Mark. The building had a red hip roof that continued down over the ground floor on the northern side. Olbrich himself had also designed the entire interior. The house was heavily damaged in World War II.[17] It was rebuilt in 1950–1951, although everything above the ground floor was completely changed. Only the white and blue tiles on the facade recall the original construction. It was used by the German Polish Institute from 1980 to 1996.[13]

Ludwig Habich's House

editJoseph Maria Olbrich was the architect of the Ludwig Habich's House,[18] which was the studio and residence of sculptor Ludwig Habich. Patriz Huber was responsible for the interior design. The building is notable for its flat roof and solid geometry with its Spartan decoration. After suffering serious damage during the war, it was rebuilt in 1951 with certain changes in the details but in accordance with the original plans.

Hans Christiansen's House

editThe House Christiansen was designed by Olbrich in accordance with painter Hans Christiansen's wishes. The facade was dominated by large areas of colour, but the decoration was at times also figurative. It was painted by Christiansen and offered plenty of material for discussion. The artist and his family lived in the house for quite some time, even though Christiansen worked for the most part outside of Darmstadt in later years. The building was completely destroyed in World War II and not reconstructed. A gap was left where it had stood, thereby also destroying the original symmetry of the area.

Georg Keller's House

editThis house, known as "Beaulieu" was erected for the well-off Georg Keller according to plans drawn up by Joseph Maria Olbrich. Following its destruction in the war, it was rebuilt completely differently.

Second Exhibition 1904

editThe second exhibition featured almost only temporary constructions after the large financial losses of the first exhibition. The remaining members Olbrich and Habich had been joined at this time by three new members: Johann Vincenz Cissarz, Daniel Greiner and Paul Haustein.

Group of three houses

editThe three interconnected houses at the corner of the Stiftstraße and Prinz-Christians-Weg were built in 1904 according to plans by Joseph Maria Olbrich. The corner house (with pilaster strips made of bricks) and the "Blue House" (the ground floor is covered with blue-glazed tiles) were erected to be sold, while the "Grey House", also known as the "Preacher House", (which has a dark rough plaster surface) was designed as a residence for the court preacher. Olbrich designed the interior of the Grey House; Paul Haustein and Johann Vincenz Cissarz were responsible for the décor of the Blue House and some rooms of the corner house. The three houses were intended to demonstrate living possibilities for the middle classes. They were heavily damaged in World War II. The Grey House made way for a new construction, while the other two were reconstructed with serious modifications.

Third Exhibition (Hesse regional exhibition) 1908

editThe third exhibition, which was open to artists and craftsmen from Hesse, was centred on a colony of small residences, in order to show that modern forms of living were attainable with limited financial means. The exhibition's theme was free and applied art. Besides Olbrich, the colony also housed Albin Müller, Jakob Julius Scharvogel, Joseph Emil Schneckendorf, Ernst Riegel, Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens and Heinrich Jobst at the time.

Exhibition Building

editJoseph Maria Olbrich planned the Wedding Tower and the neighbouring Exhibition Building, which were opened in 1908 as a venue for the members of the artists' colony to display their artistic work. The building stands on a former reservoir, part of the Darmstadt water network, which was originally only sealed over with earth.

Upper Hesse Exhibition House

editMathildenhöhe Darmstadt, Art Nouveau

This House was designed by Olbrich as a venue for displays of industrial and trade products from Upper Hesse and largely decorated by him as well. Today, the "Institute for New Music and Music Education" uses the building.

Conrad Sutter's House

editArchitect Conrad Sutter designed and built this house, as well as designing the entire interior. The building was included in the exhibition against the opinion of the jury, for which Sutter assumed the responsibility.

Wagner-Gewin House

editArchitect Johann Christoph Gewin drew up plans for the house for the builder Wagner. It was destroyed in the war.

The small residence colony

editThe small residence colony was erected on the eastern slope of the Mathildenhöhe as a model for residences for less well-off classes. It was made up of one dual occupancy house, two semi-detached houses and three single occupancy houses. The model houses were exhibited collectively by the Ernst Ludwig Society and the Hesse Central Society for the Construction of Cheaper Apartments. Six industrialist magnates from Hesse provided the financing. The conditions required the houses to have at least three residential rooms, to be made of local building materials, and not to cost more than 4000 Mark for a single occupancy house or 7200 Mark for a dual occupancy house. Moreover, the architects were required to design an interior which cost less than 1000 Mark per residence. The buildings were designed by the local architects Ludwig Mahr, Georg Metzendorf, Josef Rings, Heinrich Walbe, Arthur Wienkoop and Joseph Maria Olbrich. The fully furnished buildings were displayed in 1908 but were dismantled shortly after the end of the exhibition.

Opel Workers' House

editOlbrich was commissioned by the firm Opel from Rüsselheim to design a single occupancy house complete with the interior design as part of the small residence colony. Instead of an eat-in kitchen, which was common at the time, there was a small kitchen and a large living room in the ground floor. In the second floor, there were two large bedrooms and a bathroom.

Workers' Houses, Erbacher Straße 138–142

editThe three houses by Mahr, Metzendorf and Wienkoop were dismantled after the 1908 exhibition and moved to what is now the Erbacher Straße on commission of the nearby ducal dairy farm.

Fourth Exhibition 1914

editThe particular focus of the last exhibition was the rental residence, for which Albin Müller erected a group of eight three-storey rental apartment buildings on the northern slope of the Mathildenhöhe. Three houses included model interior designs by various colony members. The rear wing of this group was a five-storey atelier. This row of apartment buildings was destroyed in World War II, but the atelier with its brown striped southern facade survived. The sycamore grove and the lion gate (now the entrance gate to the Park Rosenhöhe) can still be seen today. The colony members at this time were Heinrich Jobst, Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens, Albin Müller, Fritz Osswald, Emanuel Josef Margold, Edmund Körner and Bernhard Hoetger.

Surrounding development

editDarmstadt's local architects did not take part in the first exhibition in the Mathildenhöhe. Traditionalists Alfred Messel (residence for museum director Paul Ostermann von Roth), Georg Metzendorf (residence for Georg Kaiser), Heinrich Metzendorf (residence for Hofrat Otto Stockhausen) and Friedrich Pützer (inter alia his own residence, the residence for Dr. Mühlberger and the dual residency house for Finanzrat Dr. Becker and Finanzrat Bornscheuer) were however able to display their concepts on the margins of the artists' colony. The exhibition terrain was surrounded by a fence only for the duration of the exhibition. The houses of the artists' colony and those of the other architects were immediately adjacent to one another in the development.

The new artists' colony in Rosenhöhe

editThe city of Darmstadt established a new artists' colony in the 1960s. Seven ateliers and residences were erected between 1965 and 1967 according to plans by Rolf Prange, Rudolf Kramer, Bert Seidel, Heribert Hausmann and Reinhold Kargel. The author Heinrich Schirmbeck, the lyricist Karl Krolow, the art historian Hans Maria Wingler and the sculptor Wilhelm Loth were (or are) amongst the inhabitants of this colony.[citation needed]

See also

edit- Vortex Garten Public garden at the art nouveau area of Mathildenhöhe

- Russian Chapel in Darmstadt

References

edit- ^ "Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt von UNESCO ausgezeichnet". Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission (in German). 24 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Meuren, Daniel (24 July 2021). "Mathildenhöhe ist UNESCO-Welterbe: "Auftrag und Verpflichtung für die Zukunft"". FAZ.NET (in German). Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Unesco-Auszeichnung: Darmstädter Mathildenhöhe ist jetzt offiziell Welterbe". hessenschau.de (in German). 24 July 2021. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Briegleb, Till (25 July 2021). "Unesco-Weltkulturerbe: Die Darmstädter Mathildenhöhe". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "1901 Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt // Ein Dokument Deutscher Kunst". IBA (in German). 5 November 2020. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Anne (2017). "'Mein Hessenland blühe und in ihm die Kunst'. Ernst Ludwig's Darmstädter Künstlerkolonie: Building Nationhood through the Arts and Crafts". Transnational Histories of the 'Royal Nation'. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 177–202. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50523-7_9. ISBN 978-3-319-50522-0.

- ^ "Mein Hessenland blühe". Akademie 55plus Darmstadt e.V. (in German). Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Mathildenhöhe". Stadtlexikon Darmstadt (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Ernst Ludwig House". Künstlerkolonie Mathildenhöhe. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Museum Künstlerkolonie Darmstadt". Museen-in-Hessen (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Haus Deiters". Künstlerkolonie Mathildenhöhe (in German). Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Mathildenhöhe Haus Deiters". goblu-architekten (in German). Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Neues Domizil für das Deutsche Polen-Institut – Deutsches Polen-Institut". Deutsches Polen-Institut (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Großes Haus Glückert". Künstlerkolonie Mathildenhöhe (in German). Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Glückert-Häuser". Stadtlexikon Darmstadt (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Der Autodidakt baute sich seine Villa auf der Mathildenhöhe einfach selbst – Architektur des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts". Architektur des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts – Vom Bauhaus bis zum Dekonstruktivismus – Fotos, Texte und mehr von Volker Hilarius (in German). 27 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Haus Olbrich". Wissenschaftsstadt Darmstadt (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Habich, Ludwig". Stadtlexikon Darmstadt (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

Further reading

edit- Bredow, Jürgen; Cramer, Johannes; Lerch, Helmut (1979). Bauten in Darmstadt : Architekturführer (in German). Darmstadt: Roether. ISBN 3-7929-0106-4. OCLC 7247953.

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- Geelhaar, Christiane; Rahe, Jochen; Darmstadt (1999). Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt : 100 Jahre Planen und Bauen für die Stadtkrone, 1899-1999 (in German). Darmstadt: Verlag Jürgen Häusser. ISBN 3-89552-063-2. OCLC 48518547.

- Herbig, Bärbel; Schröder, Doris (2012). Die Darmstädter Mathildenhöhe : Architektur im Aufbruch zur Moderne ; zwei Spaziergänge zu den Bauten der Jahrhundertwende (in German). Darmstadt: Magistrat der Stadt Darmstadt, Denkmalschutz – Kulturamt. ISBN 978-3-87390-307-4. OCLC 807050898.

- Werner, Heike; Wallner, Mathias (2006). Architektur und Geschichte in Deutschland (in German). München. ISBN 3-9809471-1-4. OCLC 636924042.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

edit- Official website (in German and English)

- Info Mathildenhöhe

- Schiedmayer grand piano from the musicroom of House Behrens 1901