Dastangoi (Urdu: داستان گوئی) is a 13th century Urdu oral storytelling art form.[1][2] [3] The Persian style of dastan evolved in 16th century.[4] One of the earliest references in print to dastangoi is a 19th-century text containing 46 volumes of the adventures of Amir Hamza titled Dastan e Amir Hamza.[5]

The art form reached its zenith in the Indian sub-continent in the 19th century and is said to have died with the demise of Mir Baqar Ali in 1928. Dastangoi was revived[6] by historian, author and director Mahmood Farooqui in 2005.[7]Syed Sahil Agha has amalgamated Dastangoi with music & singing in 2010.[8]

At the centre of dastangoi is the dastango, or storyteller, whose voice is his main artistic tool in orally recreating the dastan or the story. Notable 19th-century dastangos included Amba Prasad Rasa, Mir Ahmad Ali Rampuri, Muhammad Amir Khan, Syed Husain Jah, and Ghulam Raza.

Etymology

editDastangoi has its origin in the Persian language. Dastan means a tale; the suffix -goi makes the word mean "to tell a tale".[9]

History

editIndian urban anthropologist Ghaus Ansari ascribed the origin of dastangoi to Pre-Islamic Arabia, and detailed how the eastward spread of Islam carried dastangoi to Iran and then to Delhi in India. From Delhi, dastangoi made its way to Lucknow in the 18th century, aided by the Indian Rebellion of 1857, during which several artists, writers and dastangos moved from Delhi to Lucknow.

In Lucknow, dastangoi was popular across all classes, and was regularly performed at diverse locations including chowks (city squares), private households, and afeem khana (public opium houses). "It became so popular among opium addicts that they made listening to stories an important element of their gatherings," wrote Ansari. "The prolonged intoxication and prolonged stories narrated by professional story-tellers was mostly combined. Each afeem khana had its own story-teller to entertain the clients; whereas, among the rich, every household used to appoint a dastango as a member of its staff."[10] According to Abdul Halim Sharar, the noted author and historian of nineteenth century Lucknow, the Art of dastangoi, was divided under the following headings:"War", "Pleasure, "Beauty", "Love" and "Deception".[11]

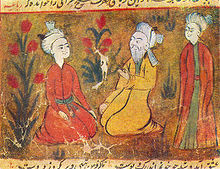

The early dastango's told tales of magic, war and adventure, and borrowed freely from other stories such as the Arabian Nights, storytellers such as Rumi, and storytelling traditions such as the Panchatantra. From the 14th century, Persian dastangois started focusing on the life and adventures of Amir Hamza, the paternal uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Indian stream of dastangoi added storytelling elements such as aiyyari (trickery) to these tales.[12]

List of early Urdu Dastans

edit- Sab Ras - Mulla Wajhi

- Nau tarz-i murassa‘ - Husain ‘Atā Khān Tahsīn

- Nau ā'īn-i hindī (Qissa-i Malik Mahmūd Gīti-Afroz) - Mihr Chand Khatrī

- Jazb-i ‘ishq - Shāh Husain Haqīqat

- Nau tarz-i murassa‘ - Muhammad Hādī a.k.a. Mirzā Mughal Ghāfil

- Ārā'ish-i mahfil (Qissa-i Hātim Tā'ī) - Haidar Bakhsh Haidarī

- Bāgh o bahār (Qissa-i chahār darwesh) - Mīr Amman

- Dāstān-i Amīr Hamza - Khalīl ‘Alī Khān Ashk

- Fasana e Ajaib - Rajab Ali Baig Suroor

- Deval Devi-Khizr Khan - (Romantic dastan of a Vaghela princess and Delhi's Khalji king) - Amir Khusrau

- Khamsa (Khamsa-e-Khusrau) five classical romances dastan: Hasht-Bihisht, Matlaul-Anwar, Khosrow and Shirin, Layla and Majnun and Aaina-Sikandari. - Amir Khusrow

Dastangoi in print

editFort William College in Kolkata published an Urdu version of the dastaan of Amir Hamza in the beginning of the 19th century.[13] Munshi Nawal Kishore, a publisher in Lucknow, began publishing the dastaans by the 1850s. A few publications were also done in Persian.

- In 1881, Nawal Kishore commissioned the print edition of the entire Hamza dastaan from three dastangos, Mohammed Husain Jah, Ahmed Husain Qamar, and Sheikh Tasadduq Husain. Over a period of twenty five years, the trio produced a collection of 46 volumes. Each volume could be read individually or as a part of the complete work.

- Dastan-e-Hind, is a collection of dastans and Indian folklore, has been performed by many artists around the globe, by Syed Sahil Agha. 2010.[14][15]

- Toh Hazireen Hua Yun... Dastan-e-Ankit Chadha - A collection of dastans woven, by Ankit Chadha. 2019.[16][17]

- Dastangoi-2 is a sequel to earlier book. It contains the collection of modern dastans written and adapted, by Mahmood Farooqui. 2019.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Walk Back In Time: Experience life in Nizamuddin Basti, the traditional way". The Indian Express. 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "How a collective of storytellers is reviving the ancient art of dastangoi". The Sunday Guardian Live. 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- ^ "Dastangoi - the Re-discovered Art of Urdu Storytelling".

- ^ اردو میں تاریخ گوئی اور داستان گوئی کی روایت اور فن

- ^ Thakur, Arnika (30 September 2011). "Dastangoi magic revives lost medieval tales". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Dastangoi - The Re-discovered Art of Urdu Storytelling". dastangoi.com. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ "Persian art of storytelling festival brings delight for Delhi theatre buffs". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ Syeda Eba (2020-02-08). "Dastangoi: Bringing stories alive". Millennium Post. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- ^ Sayeed, Vikram Ahmed (14 January 2011). "Return of dastangoi". Frontline. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Nas, Peter J.M. (1993). Urban Symbolism. Leiden: Brill. pp. 335–336. ISBN 9789004098558. Archived from the original on 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ^ Harcourt, E.S (2012). Lucknow the Last Phase of an Oriental Culture (seventh ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-563375-7.

- ^ Farooqui, Mahmood (Autumn–Winter 2011). "Dastangoi: Revival of the Mughal Art of Storytelling". Context: Journal of the Development and Research Organisation for Nature, Arts and Heritage. VIII (2): 31–37. Archived from the original on 2016-07-22. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Krishnan, Nandini (4 May 2012). "Dastaan-e-Dastangoi". Fountain Ink. Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "DastanGoi, Dastan-e-Amir kusrow". karmpatr.com. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ prakruti (2019-11-30). "On the art of storytelling: Dastango Syed Sahil Agha". www.purplepencilproject.com. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- ^ Indian Express Delhi. "Stories Never Die". epaper.indianexpress.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ Chadha, Ankit (2018). To Hazreen Hua Yun... SAKSHI PRAKASHAN. ISBN 9789384456726.

External links

edit- Pritchett, Frances W. (1991). The Romance Tradition in Urdu : Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231071642. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Farooqui, Mahmood (Autumn–Winter 2011). "Dastangoi: Revival of the Mughal art of storytelling". Context: Journal of the Development and Research Organisation for Nature Arts and Heritage. VIII (2): 31–37. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Ghalib Lakhnavi & Abdullah Bilgram, trans Musharraf Ali Farooqi (2012). The Adventures of Amir Hamza: Special Abridged Edition. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-8129-7744-8.