On the Day of Daggers (French: Journée des Poignards), 28 February 1791, hundreds of nobles with concealed weapons such as daggers went to the Tuileries Palace, in Paris, to defend King Louis XVI while Marquis de Lafayette led the National Guard in Vincennes to stop a riot. A confrontation between the guards and the nobles started, as the guards thought that the nobles had come to take the King away. The nobles were finally ordered by the King to relinquish their weapons and were forcibly removed from the palace.

| Day of Daggers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French Revolution | ||||||

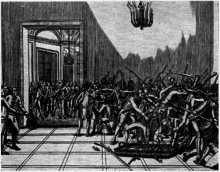

The disarming of the nobles in the Tuileries Palace on 28 February 1791 | ||||||

| ||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

| National Guard | Workmen from Faubourg Saint-Antoine | chevaliers du poignard | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

| Marquis de Lafayette | Antoine Joseph Santerre | |||||

Background

editIn the latter half of 1789, riots became a common occurrence in Paris, whose people would express their discontent with the National Assembly for an act that it created by taking to the streets and causing a violent commotion.[1] The violence in Paris contributed to an increasing number of members of the nobility emigrating from the city to seek foreign aid or to cause insurrection in the provinces to the south.[2] Although that migration began with primarily members of the first and second estates (the clergy and the nobility), the resulting French Emigration (1789–1815) was a mass movement of thousands of Frenchmen spanning various socioeconomic classes. Additionally, even though the violence in Paris provided an immediate reason for emigration, many of the upper classes also fundamentally disagreed with the Revolution's degradation of the Ancien Régime, which had offered privileges to which the nobility had grown accustomed.

Among the emigrating nobles were the aunts of King Louis XVI, Madame Adélaïde and Madame Victoire. The Mesdames believed that it was their duty to seek safety near the Pope, and on 19 February 1791, they set off on a pilgrimage to Rome. They were, however, stopped in the municipality of Arnay-le-Duc, which started a prolonged debate in the National Assembly over the departure of the Mesdames that was ended by the statesman Jacques-François Menou joking about the Assembly's preoccupation with the actions of "two old women". The Mesdames were then permitted to continue their trip.[3]

As a result of the French Emigration of nobles, along with the debacle over the Mesdames, rumours began circulating that King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette would soon follow the example of the Mesdames by fleeing Paris. On 24 February 1791, a large group of alarmed and confused protesters went to the Tuileries Palace, where the King resided, and sought to petition him to recall his aunts. The mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, attempted to act as an intermediary by offering to allow a smaller contingent of 20 delegates into the palace to see the King. However, the National Guard, led by the Marquis de Lafayette, remained firm in not admitting anyone and by dispersing the crowd after a three-hour standoff.[4][5]

Day of Daggers

editWhile the idea of the King's conspiracy to leave France grew in Paris, the municipality voted to restore the dungeons of the Château de Vincennes to accommodate more prisoners. However, a rumour developed, claiming that there was an underground passage between the Tuileries and the Château. Suddenly, people believed that the restoration was part of a conspiracy to disguise the passage and allow for the King to leave France secretly .[6] Thus, on 28 February 1791, workmen from the faubourgs who were armed with pickaxes and pikes followed the lead of Antoine Joseph Santerre to Vincennes to demolish the prison. The goals of the workmen were to prevent the King from escaping through the Château and dismantling "the last remaining Institution of the Country".[7][8]

While Lafayette led a contingent of the National Guard to Vincennes to quell the riot there, many nobles became worried about the safety of the King with the absence of the guard. Worried about a Jacobin conspiracy to murder the royal family and the court, hundreds of young nobles with concealed weapons such as daggers and knives went to the Tuileries to defend the King.[9] However, the remaining officers of the National Guard began to suspect that the armed nobles arrived as part of a counter-revolution.[10] Lafayette quickly returned from Vincennes and attempted to disarm the nobles. The nobles resisted until the King, who wanted to avoid a major conflict, requested them to lay down their weapons with the promise that their weapons would be returned the next day. The nobles finally gave in and left the Tuileries after they had been thoroughly searched, mocked, and maltreated by the National Guard.[7]

The following day, Lafayette posted a proclamation on the walls of the capital that notified the National Guard that no more men "of a justly suspected zeal" would be permitted into the Tuileries.[7] The confiscated weapons of the nobles were seized by the soldiers and sold off.[11]

Consequences

editThe conflict on 28 February, later deemed the Day of Daggers, humiliated the monarchists who had come to the Tuileries to defend the King. The specific actions of Lafayette the day afterward reaffirmed the rumour that the nobles had planned to take away the King and thus created the legend of the conspiracy of the chevaliers du poignard.[12] That was used in propaganda images from the constitutionalists. One particular cartoon, "The Disarmament of the Good Nobility," by the engraver Villeneuve showed the "exact form" of the infamous daggers that were used: a deformed dagger with inscriptions claiming that the blade had been forged by aristocrats and that the monarchists who had been led astray by the priests.[13]

Additionally, the respect and the power of King Louis XVI was further diminished by his actions on that day. The monarchists felt betrayed by his siding with the National Guard, and the radical press spun the events as an abortive attempt at a counter-revolution.[10] It is thought that this incident helped to cement the King's decision to flee Paris on 20 June 1791 because of his dissatisfaction with his waning power, the increase of the restrictions that were placed upon him and his disagreement with the National Assembly on the topic of the Catholic priests.[3]

References

edit- ^ Rocheterie, Maxime de La (1893). The Life of Marie Antoinette. J.R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Company. pp. 109.

- ^ Thiers, Marie Joseph L Adolphe (1845). The History of the French Revolution. pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b Thiers, p. 62

- ^ Rocheterie, p. 110

- ^ Caiani, Ambrogio A (20 September 2012). Louis XVI and the French Revolution, 1798–1792. Cambridge University Press. p. 94.

- ^ Roberts, Warren (2000). Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Louis Prieur, Revolutionary Artists. SUNY Press. pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b c Rocheterie, p. 111

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1914). The French Revolution: A History. J.M. Dent. pp. 335–336.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin Huntly (1898). The French Revolution,. Harper. p. 541.

- ^ a b Caiani, p. 95

- ^ McCarthy, p. 542

- ^ Rocheterie, p. 112

- ^ Henderson, Ernest Flagg (1912). Symbol and satire in the French Revolution. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 167.

Sources

edit- Caiani, Ambrogio A (20 September 2012). Louis XVI and the French Revolution, 1798–1792. Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1914). The French Revolution: A History. J.M. Dent. pp. 335–336.

- Henderson, Ernest Flagg (1912). Symbol and satire in the French Revolution. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 167.

- McCarthy, Justin Huntly (1898). The French Revolution,. Harper. pp. 541–542.

- Roberts, Warren (2000). Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Louis Prieur, Revolutionary Artists. SUNY Press. pp. 149–151.

- Rocheterie, Maxime de La (1893). The Life of Marie Antoinette. J.R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Company. pp. 109–112.

- Thiers, Marie Joseph L Adolphe (1845). The History of the French Revolution. pp. 61–62.