Deep End is a 1970 psychological comedy drama film directed by Jerzy Skolimowski and starring Jane Asher, John Moulder Brown and Diana Dors.[1] It was written by Skolimowski, Jerzy Gruza and Boleslaw Sulik. The film was an international co-production between West Germany and the United Kingdom. Set in London, the film centers on a 15-year-old boy who develops an infatuation with his older, beautiful co-worker at a suburban bath house and swimming pool.

| Deep End | |

|---|---|

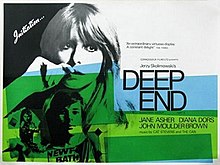

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jerzy Skolimowski |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Helmut Jedele |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charly Steinberger |

| Edited by | Barrie Vince |

| Music by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival on 1 September 1970. Deep End, considered a cult classic, went unreleased for many years due to rights issues. In 2011, it was given a digital restoration with the cooperation of the British Film Institute and was released in theaters and on home media.

Plot

editMike, a 15-year-old dropout, finds a job in a public bath in East London. He is trained by his colleague Susan, a woman 10 years his senior. Susan is a tease who plays with Mike's and other men's feelings, sometimes warm and affectionate and sometimes cold and distant. Mike's first female client is sexually stimulated by pushing his head into her bosom and talking suggestively about George Best. Mike is confused by this, and at first does not want to accept the tip he receives from her, but Susan tells him that sexual services are a normal practice at the baths and encourages him to serve some of her female clients for larger tips.

Mike fantasises about Susan and falls in love with her, but she has a wealthy young fiancé, Chris. Mike also discovers that Susan is cheating on Chris with Mike's former physical education teacher, who works at the baths as a swim instructor for teenage girls whom he touches inappropriately. Mike follows Susan on her dates with Chris and the instructor and tries to disrupt them. Susan becomes angry at Mike after he follows her and Chris into an adult movie theater and touches her breast, but provides just enough encouragement for him to continue. Mike's infatuation with Susan continues despite his friends mocking him, Susan mocking his mother and running over his bicycle with her car, and his activities drawing the ire of Susan's boyfriends, the local police, and their boss. Mike refuses other outlets for sex, such as his former girlfriend who comes to the baths and flirts with him and a prostitute in Soho who offers him a discount.

While following Susan on a date, Mike sees and steals an advertising photo cutout of a stripper who resembles her. He confronts Susan with it on the London Underground, flying into a violent tantrum when Susan teasingly refuses to tell him whether or not she is the woman in the photo. Mike then takes the cutout to the baths after hours and swims naked with it.

The next morning, Mike disrupts a foot race directed by the physical education teacher and punctures the tyres of his car while Susan is driving it. Susan grows angry and hits Mike, knocking the diamond off of her new engagement ring. Anxious to find the lost diamond, Mike and Susan collect the surrounding snow in plastic bags and take it back to the closed baths to melt it, using exposed electrical wiring from a lowered ceiling lamp to heat an electric kettle in the empty pool. While Susan is briefly out of the room, Mike finds the diamond and lies down naked with it on his tongue. He teases Susan by showing her the diamond but refusing to give it to her until she undresses. She complies and he gives her the diamond; as she is about to leave, she reconsiders and lies down next to him in the pool. They have a sexual encounter, although it is not clear whether or not Mike is able to perform.

Chris then telephones, and Susan rushes around the empty pool hurriedly gathering her clothes to go and meet him. Mike begs her to stay and talk to him. Meanwhile, an attendant arrives and opens the valve to start filling the pool with water. Mike becomes more insistent, chasing Susan around the rapidly filling pool, and finally hitting her in the head with the ceiling lamp, injuring her. Dazed, she stumbles and falls into the water, as the lamp knocks a can of red paint into the pool. Mike embraces the nude Susan underwater, just as he embraced the photo cutout. Water continues to fill the pool, with the live wire dangling within.

Cast

edit- Jane Asher as Susan

- John Moulder-Brown as Mike

- Karl Michael Vogler as swimming instructor

- Christopher Sandford as Chris

- Diana Dors as Mike's first lady client

- Louise Martini as prostitute

- Erica Beer as baths cashier

- Anita Lochner as Kathy

- Annemarie Kuster as nightclub receptionist

- Cheryl Hall as red hat girl

- Christina Paul as white cloth girl

- Dieter Eppler as stoker

- Karl Ludwig Lindt as baths manager

- Eduard Linkers as cinema owner

- Will Danin as younger policeman

- Gerald Rowland as Mike's friend

- Burt Kwouk as hot dog stand man

- Ursula Mellin as Mike's second lady client (uncredited)

- Erika Wackernagel as Mike's mother (uncredited)

- Uli Steigberg as Mike's father/policeman (uncredited)

- Peter Martin Urtel as older policeman (uncredited)

- Jerzy Skolimowski as passenger on tube reading Polish newspaper (uncredited)

Production

editFilming

editThe film was made in about six months from conception to completion.[2] It was shot largely in Munich, with some exterior scenes shot in Soho and Leytonstone in London.[2] The cast members could improvise and were told to remain in character even when a scene was not going as planned.[2] Many years after the film's release, Asher denied suggestions that she had used a body double for some of her scenes: "I certainly didn't! ... And, looking back, I like the way it's done."[3]

Music

editThe film features the song "Mother Sky" by Can in an extended sequence set in Soho,[4] and "But I Might Die Tonight" by Cat Stevens in the opening scene and finale;[2] the previously unreleased version heard in the film was eventually released in 2020 on a reissue of Stevens' album Tea for the Tillerman.[5]

Reception

editCritical reception

editThe film received critical acclaim. In The Guardian, Ryan Gilbey wrote: "The consensus when it premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September 1970 was that it would have been assured of winning the Golden Lion, if only the prize-giving hadn't been suspended the previous year."[2] Penelope Gilliatt of The New Yorker called it "a work of peculiar, cock-a-hoop gifts".[2] Variety praised the lead actors and "Skolimowsky's frisky, playful but revealing direction".[6] Nigel Andrews of The Monthly Film Bulletin called the film "a study in the growth of obsession that is both funny and frighteningly exact".[7]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four and called it "a stunning introduction to a talented film maker", praising the "delicious humor and eroticism" as Skolimowski "plays with the audience much in the same way that Miss Asher entices Brown".[8] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called Deep End "a masterpiece" that "shows Skolimowski to be a major film-maker, impassioned yet disciplined. He runs an eloquent camera and evokes fine performances".[9] Film critic Andrew Sarris described it as "the best of Godard, Truffaut, and Polanski, and then some; nothing less, in fact, than a work of genius on the two tracks of cinema, the visual and the psychological".[10][11]

Some critics disliked the ending, which they saw as too downbeat.[2][12] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four, calling it an "observant and sympathetic movie", but criticizing its ending.[13] Roger Greenspun of The New York Times wrote: "Although it has a strong and good story, Deep End is put together out of individual, usually comic routines. Many of these don't work, but many more work very well."[14] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote: "Judging from Deep End, Skolimowski has a fairly distinctive film personality, but it happens to be a split personality, split in a way – half-Truffaut, half-Polanski – that I find rather disconcerting and unappealing. Imagine a film like Stolen Kisses [turning, at about the half-way point, into a film like Repulsion [1965] and you have Deep End."[15]

Critics also lauded Skolimowski's strategic use of colour.[14][12] In an interview with NME in 1982, David Lynch said of Deep End: "I don't like colour movies and I can hardly think about colour. It really cheapens things for me and there's never been a colour movie I've freaked out over except one, this thing called Deep End, which had really great art direction."[16]

Writing of the film's restoration in 2011, The Guardian's Steve Rose wrote, "Deep End is bravely ambiguous and disjointed, lurching unpredictably between comedy and creepiness; but the characters are bracingly down to earth…In fact, everything about this singular film – the camerawork, the imagery, the soundtrack – feels vibrant and surprising in a way that makes most modern coming-of-age movies look formulaic and, well, shallow."[17] Slant Magazine's Jaime N. Christley praised "Skolimowski's hallucinatory, dissonant, yet compelling tale of hormonal confusion".[18] In The Village Voice, Michael Atkinson called it a "strangely impetuous study of coming-of-age sexual muddle, full of whimsy and abrupt ideas, and intoxicated from a distance, it seems, by Swinging London's free-love commerce".[19]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 90% based on 20 reviews, with an average rating of 7.8/10.[20]

Accolades

editJane Asher was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role.[21]

Restoration

editIn 2009, Bavaria Media, a subsidiary of Bavaria Film, which co-produced the film in 1970 through its subsidiary Maran Film, began a digital restoration in honor of the film's 40th anniversary, in cooperation with the British Film Institute.[22] The restored film was re-released in UK cinemas on 6 May 2011 and on Blu-ray Disc and DVD on 18 July 2011 as part of the BFI Flipside series.[23] The disc extras included the documentary Starting Out: The Making of Jerzy Skolimowski's Deep End and deleted scenes.[24]

References

edit- ^ "Deep End". British Film Institute. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gilbey, Ryan (1 May 2011). "Deep End: pulled from the water". The Guardian.

- ^ "Interview with David Hayles". The Times. May 2011.

- ^ "Can's «Mother Sky» in Skolimowsky's «Deep End» (1970)". norient.com. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Deep End". Yusuf / Cat Stevens. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Deep End". Variety. 16 September 1970. p. 23.

- ^ Andrews, Nigel (April 1971). "Deep End". The Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 38, no. 447. p. 71. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (30 November 1971). "2 on Teen-Age Love". Chicago Tribune. p. 5.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (26 August 1971). "Growing Up Theme of 'Deep End'". Los Angeles Times. p. 23.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (19 August 1971). "Films in Focus: Deep End". The Village Voice. p. 45. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Weedman, Christopher (10 December 2015). "Optimism Unfulfilled: Jerzy Skolimowski's Deep End and the "Swinging Sixties"". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b Smith, Richard Harland (3 September 2009). "The Gist (Deep End)". Turner Classic Movie Database. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1 December 1971). "Deep End". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 28 May 2019 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b Greenspun, Roger (11 August 1971). "Screen: 'Deep End,' Fantasies in a Public Bath". The New York Times. p. 42. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (23 September 1971). "Skolimowski's 'Deep End'". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ McKenna, Kristine (21 August 1982). "Out to Lynch". NME. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012 – via DavidLynch.de.

- ^ Rose, Steve (5 May 2011). "Deep End – review". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Christley, Jaime N. (13 December 2011). "Review: Deep End". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Atkinson, Michael (14 December 2011). "The Limits of Free Love in Deep End". The Village Voice. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Deep End". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ "Film in 1972". BAFTA Awards. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (15 May 2009). "Bavaria restoring 'Deep End'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "A New Digital Restoration – Deep End" (PDF) (Press release). British Film Institute. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Galloway, Chris (27 July 2011). "Deep End". Criterion Forum. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

External links

edit- Deep End at IMDb

- Deep End at AllMovie

- Deep End at BritMovie (archived)

- Deep End at Rotten Tomatoes

- Deep End at the British Film Institute

- Deep End at the TCM Movie Database

- Deep End: Ripe for Rediscovery at TCM Movie Morlocks