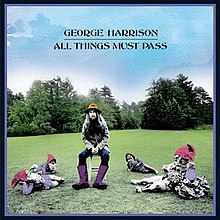

All Things Must Pass is the third studio album by the English rock musician George Harrison. Released as a triple album in November 1970, it was Harrison's first solo work after the break-up of the Beatles in April that year. It includes the hit singles "My Sweet Lord" and "What Is Life", as well as songs such as "Isn't It a Pity" and the title track that had been overlooked for inclusion on releases by the Beatles. The album reflects the influence of Harrison's musical activities with artists such as Bob Dylan, the Band, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends and Billy Preston during 1968–70, and his growth as an artist beyond his supporting role to former bandmates John Lennon and Paul McCartney. All Things Must Pass introduced Harrison's signature slide guitar sound and the spiritual themes present throughout his subsequent solo work. The original vinyl release consisted of two LPs of songs and a third disc of informal jams titled Apple Jam. Several commentators interpret Barry Feinstein's album cover photo, showing Harrison surrounded by four garden gnomes, as a statement on his independence from the Beatles.

| All Things Must Pass | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 27 November 1970 | |||

| Recorded | May–October 1970 | |||

| Studio | EMI, Trident and Apple (London) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 106:00 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Producer | ||||

| George Harrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from All Things Must Pass | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

Cover of the 2001 reissue | ||||

Production began at London's EMI Studios in May 1970, with extensive overdubbing and mixing continuing through October. Among the large cast of backing musicians were Eric Clapton and members of Delaney & Bonnie's Friends band – three of whom formed Derek and the Dominos with Clapton during the recording – as well as Ringo Starr, Gary Wright, Billy Preston, Klaus Voormann, John Barham, Badfinger and Pete Drake. The sessions produced a double album's worth of extra material, most of which remains unissued.

All Things Must Pass was critically and commercially successful on release, with long stays at number one on charts worldwide. Co-producer Phil Spector employed his Wall of Sound production technique to notable effect; Ben Gerson of Rolling Stone described the sound as "Wagnerian, Brucknerian, the music of mountain tops and vast horizons".[2] Reflecting the widespread surprise at the assuredness of Harrison's post-Beatles debut, Melody Maker's Richard Williams likened the album to Greta Garbo's first role in a talking picture and declared: "Garbo talks! – Harrison is free!"[3] According to Colin Larkin, writing in the 2011 edition of his Encyclopedia of Popular Music, All Things Must Pass is "generally rated" as the best of all the former Beatles' solo albums.[4]

During the final year of his life, Harrison oversaw a successful reissue campaign to mark the 30th anniversary of the album's release. After this reissue, the Recording Industry Association of America certified the album six-times platinum. It has since been certified seven-times platinum, with at least 7 million albums sold. Among its appearances on critics' best-album lists, All Things Must Pass was ranked 79th on The Times' "The 100 Best Albums of All Time" in 1993, while Rolling Stone placed it 368th on the magazine's 2023 update of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". In 2014, All Things Must Pass was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Background

editMusic journalist John Harris said George Harrison's "journey" to making All Things Must Pass started when he visited America in late 1968, after the acrimonious sessions for the Beatles' self-titled double album (also known as the "White Album").[5] At Woodstock in November,[6] Harrison started a long-lasting friendship with Bob Dylan[5] and experienced a creative equality with the Band that contrasted with John Lennon and Paul McCartney's dominance in the Beatles.[7][8] He also wrote more songs,[9] renewing his interest in the guitar after three years studying the Indian sitar.[10][11] As well as being one of the few musicians to co-write songs with Dylan,[5] Harrison had recently collaborated with Eric Clapton on "Badge",[12] which became a hit single for Cream in the spring of 1969.[13]

Once back in London, and with his compositions continually overlooked for inclusion on releases by the Beatles,[14][15] Harrison found creative fulfilment in extracurricular projects that, in the words of his musical biographer, Simon Leng, served as an "emancipating force" from the restrictions imposed on him in the band.[16] His activities during 1969 included producing Apple signings Billy Preston and Doris Troy, two American singer-songwriters whose soul and gospel roots proved as influential on All Things Must Pass as the music of the Band.[17] He also recorded with artists such as Leon Russell[18] and Jack Bruce,[19] and accompanied Clapton on a short tour with Delaney Bramlett's soul revue, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends.[20] In addition, Harrison identified his involvement with the Hare Krishna movement as providing "another piece of a jigsaw puzzle" that represented the spiritual journey he had begun in 1966.[21] As well as embracing the Vaishnavist branch of Hinduism, Harrison produced two hit singles during 1969–70 by the UK-based devotees, credited as Radha Krishna Temple (London).[22] In January 1970,[23] Harrison invited American producer Phil Spector to participate in the recording of Lennon's Plastic Ono Band single "Instant Karma!"[24][25] This association led to Spector being given the task of salvaging the Beatles' Get Back rehearsal tapes, released officially as the Let It Be album (1970),[26][27] and later co-producing All Things Must Pass.[28]

Harrison first discussed the possibility of making a solo album of his unused songs during the ill-tempered Get Back sessions, held at Twickenham Film Studios in January 1969.[29][30][nb 1] On 25 February, his 26th birthday,[33] Harrison recorded demos of "All Things Must Pass" and two other compositions that had received little interest from Lennon and McCartney at Twickenham.[34][35] With the inclusion of one of these songs – "Something" – and "Here Comes the Sun" on the Beatles' Abbey Road album in September 1969, music critics acknowledged that Harrison had bloomed into a songwriter to match Lennon and McCartney.[36][37] He began talking publicly about recording his own album from the autumn of 1969,[38][39] but only committed to the idea after McCartney announced that he was leaving the Beatles in April 1970.[40] Included as part of the promotional material for McCartney's self-titled solo album, this announcement signalled the band's break-up.[41] Despite having already made Wonderwall Music (1968), a mostly instrumental soundtrack album, and the experimental Electronic Sound (1969),[42] Harrison considered All Things Must Pass to be his first solo album.[43][nb 2]

Songs

editMain body

editI went to George's Friar Park ... and he said, "I have a few ditties for you to hear." It was endless! He had literally hundreds of songs and each one was better than the rest. He had all this emotion built up when it was released to me.[47]

– Phil Spector, on first hearing Harrison's backlog of songs in early 1970

Spector first heard Harrison's stockpile of unreleased songs early in 1970, when visiting his recently purchased home, Friar Park.[47] "It was endless!" Spector later recalled of the recital, noting the quantity and quality of Harrison's material.[48] Harrison had accumulated songs from as far back as 1966; both "Isn't It a Pity" and "Art of Dying" date from that year.[49] He co-wrote at least two songs with Dylan while in Woodstock,[50] one of which, "I'd Have You Anytime", appeared as the lead track on All Things Must Pass.[51] Harrison also wrote "Let It Down" in late 1968.[52]

He introduced the Band-inspired[53] "All Things Must Pass", along with "Hear Me Lord" and "Let It Down", at the Beatles' Get Back rehearsals, only to have them rejected by Lennon and McCartney.[54][55][nb 3] The tense atmosphere at Twickenham fuelled another All Things Must Pass song, "Wah-Wah",[59] which Harrison wrote in the wake of his temporary departure from the band on 10 January 1969.[60] Harrison later confirmed that the song was a "swipe" at McCartney.[61] "Run of the Mill" followed soon afterwards, its lyrics focusing on the failure of friendships within the Beatles[62] amid the business problems surrounding their Apple organisation.[63] Harrison's musical activities outside the band during 1969 inspired other songs on the album: "What Is Life" came to him while driving to a London session that spring for Preston's That's the Way God Planned It album;[64] "Behind That Locked Door" was Harrison's message of encouragement to Dylan,[65] written the night before the latter's comeback performance at the Isle of Wight Festival;[66] and Harrison began "My Sweet Lord" as an exercise in writing a gospel song[67] during Delaney & Bonnie's stopover in Copenhagen in December 1969.[68][nb 4]

"I Dig Love" resulted from Harrison's early experiments with slide guitar, a technique to which Bramlett had introduced him,[67] in order to cover for guitarist Dave Mason's departure from the Friends line-up.[71] Other songs on All Things Must Pass, all written during the first half of 1970, include "Awaiting on You All", which reflected Harrison's adoption of chanting through his involvement with the Hare Krishna movement;[72][73] "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)", a tribute to the original owner of Friar Park;[74] and "Beware of Darkness".[75] The latter was another song influenced by Harrison's association with the Radha Krishna Temple,[76] and was written while some of the devotees were staying with him at Friar Park.[77]

On 1 May 1970, shortly before beginning work on All Things Must Pass, Harrison attended a Dylan session in New York,[78] during which he acquired a new song of Dylan's, "If Not for You".[59] Harrison wrote "Apple Scruffs", which was one of a number of Dylan-influenced songs on the album,[79] towards the end of production on All Things Must Pass, as a tribute to the diehard fans who had kept a vigil outside the studios where he was working.[73][80]

According to Leng, All Things Must Pass represents the completion of Harrison's "musical-philosophical circle", in which his 1966–68 immersion in Indian music found a Western equivalent in gospel music.[81] While identifying hard rock, country and Motown among the other genres on the album, Leng writes of the "plethora of new sounds and influences" that Harrison had absorbed through 1969 and now incorporated, including "Krishna chants, gospel ecstasy, Southern blues-rock [and] slide guitar".[82] The melodies of "Isn't It a Pity" and "Beware of Darkness" have aspects of Indian classical music, and on "My Sweet Lord", Harrison combined the Hindu bhajan tradition with gospel.[83] Rob Mitchum of Pitchfork describes the album as "dark-tinged Krishna folk-rock".[84]

The recurrent lyrical themes are Harrison's spiritual quest, as it would be throughout his solo career,[85] and friendship, particularly the failure of relationships among the Beatles.[86][87] Music journalist Jim Irvin says that Harrison sings of "deep love – for his faith, for life and the people around him". He adds that the songs are performed with "tension and urgency" as if "the whole thing is happening on the edge of a canyon, an abyss into which the '60s is about to topple".[88]

Apple Jam

editOn the original LP's third disc, titled Apple Jam, four of the five tracks – "Out of the Blue", "Plug Me In", "I Remember Jeep" and "Thanks for the Pepperoni" – are improvised instrumentals built around minimal chord changes,[89] or in the case of "Out of the Blue", a single-chord riff.[90] The title for "I Remember Jeep" originated from the name of Clapton's dog, Jeep,[91] and "Thanks for the Pepperoni" came from a line on a Lenny Bruce comedy album.[92] In a December 2000 interview with Billboard magazine, Harrison explained: "For the jams, I didn't want to just throw [them] in the cupboard, and yet at the same time it wasn't part of the record; that's why I put it on a separate label to go in the package as a kind of bonus."[93][nb 5]

The only vocal selection on Apple Jam is "It's Johnny's Birthday", sung to the tune of Cliff Richard's 1968 hit "Congratulations", and recorded as a gift from Harrison to Lennon to mark the latter's 30th birthday.[95] Like all the "free" tracks on the bonus disc,[96] "It's Johnny's Birthday" carried a Harrison songwriting credit on the original UK release of All Things Must Pass,[97] while on the first US copies, the only songwriting information on the record's face labels was the standard inclusion of a performing rights organisation, BMI.[98] In December 1970, "Congratulations" songwriters Bill Martin and Phil Coulter claimed royalties,[95] with the result that the composer's credit for Harrison's track was swiftly changed to acknowledge Martin and Coulter.[91]

Demo tracks and outtakes

editAside from the seventeen songs issued on discs one and two of the original album,[99] Harrison recorded at least twenty other songs – either in demo form for Spector's benefit, just before recording got officially under way in late May, or as outtakes from the sessions.[100][101] In a 1992 interview, Harrison commented on the volume of material: "I didn't have many tunes on Beatles records, so doing an album like All Things Must Pass was like going to the bathroom and letting it out."[102][nb 6]

Harrison's solo performance for Spector included six compositions that, until their inclusion on the Deluxe editions of the album's 50th anniversary box set, were only available on bootleg compilations, such as Beware of ABKCO![103][104] The six songs are: "Window, Window", another song turned down by the Beatles in January 1969;[105] "Everybody, Nobody", the melody of which Harrison adapted for "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp";[103] "Nowhere to Go", a second Harrison–Dylan collaboration from November 1968 (originally known as "When Everybody Comes to Town");[106] and "Cosmic Empire", "Mother Divine" and "Tell Me What Has Happened to You".[30][107] Also from this performance were two tracks that Harrison returned to in later years.[100] He completed "Beautiful Girl" for inclusion on his 1976 album Thirty Three & 1/3.[30] "I Don't Want to Do It", written by Dylan, was Harrison's contribution to the soundtrack for the 1985 film Porky's Revenge![59]

During the main sessions for All Things Must Pass, Harrison taped or routined early versions of "You", "Try Some, Buy Some" and "When Every Song Is Sung".[108][109] Harrison offered these three songs to Ronnie Spector in February 1971 for her proposed solo album on Apple Records.[110] After releasing his own versions of "Try Some, Buy Some" and "You",[111] he offered "When Every Song Is Sung" (since retitled "I'll Still Love You") to former bandmate Ringo Starr for his 1976 album Ringo's Rotogravure.[112] "Woman Don't You Cry for Me", written in December 1969 as his first slide-guitar composition,[113] was another song that Harrison revisited on Thirty Three & 1/3.[71] Harrison included "I Live for You" as the only all-new bonus track on the 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass.[114] "Down to the River" remained unused until he reworked it as "Rocking Chair in Hawaii"[115] for his final studio album, the posthumously released Brainwashed (2002).[116]

Harrison recorded the following songs during the All Things Must Pass sessions but, until their inclusion on some editions of the 50th anniversary box set, they had never received an official release:[117]

- "Dehradun" (or "Dehra Dun") – written during the Beatles' stay in Rishikesh in early 1968, and unveiled by Harrison in a brief performance on ukulele for the 1995 TV broadcast of The Beatles Anthology[100]

- "Gopala Krishna" – also known as "Om Hare Om",[109] with all-Sanskrit lyrics,[118] and described by Simon Leng as a "rocking companion" to "Awaiting on You All"[119]

- "Going Down to Golders Green" – a Sun Records-era Presley parody based on the melody of "Baby Let's Play House".[109]

Contributing musicians

editThe precise line-up of contributing musicians is open to conjecture.[120][121] Due to the album's big sound and the many participants on the sessions, commentators have traditionally referred to the grand, orchestral nature of this line-up.[122][123] In 2002, music critic Greg Kot described it as "a who's who of the decade's rock royalty",[54] while Harris writes of the cast taking on "a Cecil B. De Mille aspect".[59]

The musicians included Bobby Whitlock, Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, Bobby Keys, Jim Price and Dave Mason,[124] all of whom had recently toured with Delaney & Bonnie.[125] Along with Eric Clapton, there were also musicians whose link with Harrison went back some years, such as Ringo Starr, Billy Preston and German bassist Klaus Voormann,[126] the latter formerly of Manfred Mann and a friend since the Beatles' years in Hamburg.[127] Handling much of the keyboard work with Whitlock was Gary Wright,[120] who went on to collaborate regularly with Harrison throughout the 1970s.[128]

That was the great thing about [the Beatles] splitting up: to be able to go off and make my own record ... And also to be able to record with all these new people, which was like a breath of fresh air.[30]

– George Harrison, December 2000

From within Apple's stable of musicians, Harrison recruited the band Badfinger, future Yes drummer Alan White, and Beatles assistant Mal Evans on percussion.[129][130] Badfinger drummer Mike Gibbins' powerful tambourine work led to Spector giving him the nickname "Mr Tambourine Man", after the Dylan song.[59] According to Gibbins, he and White played most of the percussion parts on the album, "switch[ing] on tambourine, sticks, bells, maracas ... whatever was needed".[131] Gibbins' bandmates Pete Ham, Tom Evans and Joey Molland provided rhythm acoustic-guitar parts that, in keeping with Spector's Wall of Sound principles, were to be "felt but not heard".[73] Other contributors included Procol Harum's Gary Brooker, on keyboards, and pedal steel player Pete Drake,[132] the last of whom Harrison flew over from Nashville for a few days of recording.[133]

Adding to his and Badfinger's acoustic guitars on some All Things Must Pass tracks, Harrison invited Peter Frampton to the sessions.[134] Although uncredited for his contributions, Frampton also played acoustic guitar on the country tracks featuring Drake;[134] he and Harrison later overdubbed further rhythm parts on several songs.[134][nb 7] Orchestral arranger John Barham also attended the sessions, occasionally contributing on harmonium and vibraphone.[137] Simon Leng consulted Voormann, Barham and Molland for his chapter covering the making of All Things Must Pass and credits Tony Ashton as one of the keyboard players on both versions of "Isn't It a Pity".[138][nb 8] Ginger Baker, Clapton's former bandmate in Cream and Blind Faith, played drums on the jam track "I Remember Jeep".[109]

For contractual reasons, on UK pressings of All Things Must Pass, Clapton's participation on the first two discs remained unacknowledged for many years,[123][141] although he was listed among the musicians appearing on the Apple Jam disc.[142][143][nb 9] A pre-Genesis Phil Collins played congas at a session for "Art of Dying".[59] Harrison gave him a credit on the 30th anniversary reissue of the album,[149] but Collins' playing does not appear on the track.[150][151] Unsubstantiated claims exist regarding guest appearances by John Lennon,[152] Maurice Gibb[153] and Pink Floyd's Richard Wright.[154] In addition, for some years after the album's release, rumours claimed that the Band backed Harrison on the country-influenced "Behind That Locked Door".[155]

Production

editInitial recording

editYou could feel after the first few sessions that it was going to be a great album.[156]

– Klaus Voormann, 2003

Music historian Richie Unterberger comments that, typical of the Beatles' solo work, the precise dates for the recording of All Things Must Pass are uncertain, a situation that contrasts with the "meticulous documentation" available for the band's studio activities.[117] According to a contemporaneous report in Beatles Monthly, pre-production began on 20 May 1970,[103] the same day as the Let It Be film's world premiere.[157] Authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter cite this as the probable date for Harrison's run-through of songs for Spector.[103][nb 10] John Leckie, who worked as an EMI tape operator in 1970,[160] recalled that the sessions were preceded by a week of Harrison recording demos, accompanied by Starr and Voormann.[161] The first formal recording session for the album took place at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) on 26 May,[30][103] although Unterberger states that "much or all" of that day's recording was not used.[117]

The majority of the album's backing tracks were taped on 8-track at EMI between late May and the second week of June.[162] The recording engineer was Phil McDonald,[163] with Leckie as his tape operator.[160] Spector recorded most of the backing tracks live,[164] in some cases featuring multiple drummers and keyboard players, and as many as five rhythm guitarists.[59][158] In Whitlock's description, the studio space was a "massive room ... two sets of drums on risers, a piano, organ and other keyboards to the wall on the left, up against the far wall on the right were Badfinger, and in the centre were George and Eric and the guitars".[165] Molland recalled that, to achieve the resonant acoustic guitar sound on songs such as "My Sweet Lord", he and his bandmates were partitioned off inside a plywood structure.[166]

According to Voormann, Harrison set up a small altar containing figurines and burning incense, creating an atmosphere in which "everyone felt good."[165] Having suffered in the Beatles at McCartney's tendency to dictate how each musician should play, Harrison allowed the contributors the freedom to express themselves in their playing.[167] All the participants later recalled the project favourably.[167][nb 11]

The first song recorded was "Wah-Wah".[168][169] During the playback, Harrison was shocked at the amount of echo Spector had added, since the performance had sounded relatively dry through the musicians' headphones.[165][170] Voormann immediately "loved" the sound,[165] as did Clapton; Harrison later said: "I grew to like it."[170][171]

"What Is Life", versions one and two of "Isn't It a Pity", and the songs on which Drake participated, such as "All Things Must Pass" and "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp", were among the other tracks taped then.[172][nb 12] Preston recalled that Spector's approach was to have several keyboards playing the same chords in different octaves, to strengthen the sound. Preston said he had reservations about this approach but "with George's stuff it was perfect."[178] According to White, a "really good bond" formed among the musicians; the main sessions lasted three weeks and "There was no mucking around."[179] Badfinger participated in five sessions until early June,[131] when they left for an engagement in Hawaii.[100] Molland said they would record two or three songs each day, and that Harrison ran the sessions, rather than Spector.[180] Wright recalls that as the project progressed, the large cast of musicians was pared down.[181] He says that the later recording sessions featured a core group of himself, Harrison, Clapton, Starr or Gordon on drums, and Voormann or Radle playing bass.[182]

The Apple Jam instrumentals "Thanks for the Pepperoni" and "Plug Me In", featuring Harrison, Clapton and Mason each taking extended guitar solos,[183] were recorded later in June, at the Beatles' Apple Studio, and marked the formation of Clapton, Whitlock, Radle and Gordon's short-lived band Derek and the Dominos.[184] Harrison also contributed on guitar to both sides of the band's debut single, "Tell the Truth"[185] and "Roll It Over",[186] which were produced by Spector and recorded at Apple on 18 June.[184][187] The eleven-minute "Out of the Blue" featured contributions from Keys and Price,[188] both of whom began working with the Rolling Stones around this time.[189] According to Keys in his autobiography Every Night's a Saturday Night, he and Price added their horns parts to songs such as "What Is Life" after the backing tracks had been recorded. He recalls that Harrison and Price worked out the album's horn arrangements together in the studio.[190][nb 13]

Delays and distractions

editIn his 2010 autobiography, Whitlock describes the All Things Must Pass sessions as "spectacular in every way", although he says that the project was informed by Harrison's preoccupation with his former bandmates and ongoing difficulties with Klein and Apple.[192] Wright recalls Harrison's discomfort when Lennon and Yoko Ono visited the studio, saying: "His vibe was icy as he bluntly remarked, 'What are you doing here?' It was a very tense moment ..."[182] According to Whitlock, Harrison played the couple some of his new music and Lennon "got his socks blown off", much to Harrison's satisfaction.[193] The presence of Harrison's friends from the Radha Krishna Temple caused disruption during the sessions, according to Gibbins and Whitlock.[194] While echoing this view, Spector cited this as an example of how Harrison inspired tolerance, since the Temple devotees could be "the biggest pain in the necks in the world" yet Harrison "was spiritual and you knew it", which "made you like those Krishnas".[195][196]

Although Harrison had estimated in a New York radio interview that the solo album would take no more than eight weeks to complete,[197][198] recording, overdubbing and mixing on All Things Must Pass lasted for five months, until late October.[184][199] Part of the reason for this was Harrison's need to make regular visits to Liverpool to tend to his mother, who had been diagnosed with cancer.[200][201] Spector's erratic behaviour during the sessions was another factor affecting progress on the album.[59][184][202] Harrison later referred to Spector needing "eighteen cherry brandies" before he could start work, a situation that forced much of the production duties onto Harrison alone.[59][201][nb 14] At one point, Spector fell over in the studio and broke his arm.[156] He subsequently withdrew from the project due to what Madinger and Easter term "health reasons".[184]

Early in July, work on All Things Must Pass was temporarily brought to a halt as Harrison headed north to see his dying mother for the last time.[203][nb 15] EMI's growing concerns regarding studio costs added to the pressure on Harrison.[156] A further complication, according to Harris, was that Clapton had become infatuated with Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd, and adopted a heroin habit as a means of coping with his guilt.[59][nb 16]

Overdubbing

editIn Spector's absence, Harrison completed the album's backing tracks and carried out preliminary overdubs, doing much of the latter work at Trident Studios with former Beatles engineer Ken Scott. Harrison completed this stage of the project on 12 August.[184][nb 17] He then sent early mixes of many of the songs to his co-producer, who was convalescing in Los Angeles,[129] and Spector replied by letter dated 19 August with suggestions for further overdubs and final mixing.[184] Among Spector's comments were detailed suggestions regarding "Let It Down",[62] the released recording of which Madinger and Easter describe as "the best example of Spector running rampant with the 'Wall of Sound'", and an urging that he and Harrison carry out further work on the songs at Trident because of its 16-track recording desk.[209] Spector also made suggestions about overdubbing more instruments and orchestration on some tracks, but encouraged Harrison to focus on his vocals and avoid hiding his voice behind the instrumentation.[129]

John Barham's orchestrations were recorded during the next phase of the album's production,[168] starting in early September, along with many further contributions from Harrison, such as his lead vocals, slide guitar parts and multi-tracked backing vocals (the latter credited to "the George O'Hara-Smith Singers").[210][211] Barham stayed at Friar Park and created the music scores from melodies that Harrison sang or played to him on piano or guitar.[119] Leng recognises the arrangements on "pivotal" songs such as "Isn't It a Pity", "My Sweet Lord", "Beware of Darkness" and "All Things Must Pass" as important elements of the album's sound.[119]

According to Scott, he and Harrison worked alone for "weeks and months" on the overdubs, as Harrison recorded the backing vocals and lead guitar parts. In some cases, they slowed the tape down to allow Harrison to sing the high-register vocal lines.[212] Spector returned to London for the later mixing stage.[201] Scott says that Spector would visit Trident for a few hours and make suggestions on their latest mixes, and that some of Spector's suggestions were followed, others not.[213][212]

Spector has praised Harrison's guitar and vocal work on the overdubs, saying: "Perfectionist is not the right word. Anyone can be a perfectionist. He was beyond that ..."[47] Harrison's approach to slide guitar incorporated aspects of both Indian music and the blues tradition;[53] he developed a precise playing style and sound that partly evoked the fretless Indian sarod.[214] From its introduction on All Things Must Pass, Leng writes, Harrison's slide guitar became his musical signature – "as instantly recognisable as Dylan's harmonica or Stevie Wonder's".[215]

Final mixing and mastering

editIf I were doing [All Things Must Pass] now, it would not be so produced. But it was the first record ... And anybody who's familiar with Phil [Spector]'s work – it was like CinemaScope sound.[43]

– George Harrison, January 2001

On 9 October, while carrying out final mixing at EMI, Harrison presented Lennon with the recently recorded "It's Johnny's Birthday".[216][nb 18] The track featured Harrison on vocals, harmonium and all other instruments, and vocal contributions from Mal Evans and assistant engineer Eddie Klein.[95] That same month, Harrison finished his production work on Starr's 1971 single "It Don't Come Easy", the basic track for which they had recorded with Voormann in March at Trident.[218][219] Aside from his contributions to projects by Starr, Clapton, Preston and Ashton during 1970, over the following year Harrison would reciprocate the help that his fellow musicians on All Things Must Pass had given him by contributing to albums by Whitlock, Wright, Badfinger and Keys.[220][nb 19]

On 28 October, Harrison and Boyd arrived in New York, where he and Spector carried out final preparation for the album's release, such as sequencing.[129] Harrison harboured doubts about whether all the songs they had finished were worthy of inclusion. Allan Steckler, Apple Records' US manager, was "stunned" by the quality of the material and assured Harrison that he should issue all the songs.[30]

Spector's signature production style gave All Things Must Pass a heavy, reverb-oriented sound, which Harrison came to regret.[224][225][226] Whitlock says that, typical of Spector's Wall of Sound, there was some reverb on the original recordings but the effect was mostly added later.[193] In music journalist David Cavanagh's description, once abandoned by his co-producer midway through the summer, Harrison had "proceeded to out-Spector Spector" through the addition of further echo and multiple overdubs. Voormann has said that Harrison "cluttered" the album's sound in this way, and "admitted later that he put too much stuff on top".[227] According to Leckie, however, the reverb on tracks such as "My Sweet Lord" and "Wah-Wah" was recorded onto tape at the time, because Spector insisted on hearing the effects in place as they worked on the tracks.[228] Outtakes from the recording sessions became available on bootlegs in the 1990s.[229] One such unofficial release, the three-disc The Making of All Things Must Pass,[230] contains multiple takes of some of the songs on the album, providing a work-in-progress on the sequence of overdubs onto the backing tracks.[168]

Artwork

editHarrison commissioned Tom Wilkes to design a hinged box in which to house the three vinyl discs, rather than have them packaged in a triple gatefold cover.[91] Apple insider Tony Bramwell later recalled: "It was a bloody big thing ... You needed arms like an orang-utan to carry half a dozen."[144] The packaging caused some confusion among retailers, who, at that time, associated boxed albums with opera or classical works.[144]

The stark black-and-white cover photo was taken on the main lawn at Friar Park[73] by Wilkes' Camouflage Productions partner, Barry Feinstein.[91] Commentators interpret the photograph – showing Harrison seated in the centre of, and towering over, four comical-looking garden gnomes – as representing his removal from the Beatles' collective identity.[231][232] The gnomes had recently been delivered to Friar Park and placed on the lawn;[233] seeing the four figures there, and mindful of the message in the album's title, Feinstein immediately drew parallels with Harrison's former band.[144] Author and music journalist Mikal Gilmore has written that Lennon's initial negativity regarding All Things Must Pass was possibly because he was "irritated" by this cover photo;[200] Harrison biographer Elliot Huntley attributes Lennon's reaction to envy during a time when "everything [Harrison] touched turned to gold".[234][nb 20]

Apple included a poster with the album, showing Harrison in a darkened corridor of his home, standing in front of an iron-framed window.[238] Wilkes had designed a more adventurous poster, but according to Beatles author Bruce Spizer, Harrison was uncomfortable with the imagery.[239][nb 21] Some of the Feinstein photographs that Wilkes had incorporated into this original poster design appeared instead on the picture sleeves for the "My Sweet Lord" single and its follow-up, "What Is Life".[91]

Release

editImpact

editEMI and its US counterpart, Capitol Records, had originally scheduled the album for release in October 1970, and advance promotion began in September.[184] An "intangible buzz" had been "in the air for months" regarding Harrison's solo album, according to Alan Clayson, and "for reasons other than still-potent loyalty to the Fab Four".[240] Harrison's stature as an artist had grown over the past year through the acclaim afforded his songs on Abbey Road,[241][242] as well as the speculation caused by his and Dylan's joint recording session in New York.[243] Noting also Harrison's role in popularising new acts such as the Band and Delaney & Bonnie, and his association with Clapton and Cream, NME critic Bob Woffinden concluded in 1981: "All in all, Harrison's credibility was building to a peak."[241]

Music should be used for the perception of God, not jitterbugging.[200]

– George Harrison, January 1971

All Things Must Pass was released on 27 November 1970 in the United States, and on 30 November in Britain,[237] with the rare distinction of having the same Apple catalogue number (STCH 639) in both countries.[96] Often credited as rock's first triple album,[200] it was the first triple set of previously unissued music by a single act, the multi-artist Woodstock live album having preceded it by six months.[201] Adding to the commercial appeal of Harrison's songs, All Things Must Pass appeared at a time when religion and spirituality had become a trend among Western youth.[244][245] Apple issued "My Sweet Lord" as the album's first single, as a double A-side with "Isn't It a Pity" in the majority of countries.[246] Discussing the song's cultural impact, Gilmore credits "My Sweet Lord" with being "as pervasive on radio and in youth consciousness as anything the Beatles had produced".[200]

Another factor behind the album's first weeks of release was Harrison's meeting with McCartney in New York,[237] the failure of which led to McCartney filing suit in London's High Court to dissolve the Beatles' legal partnership.[247][248] Songs such as "Wah-Wah", "Apple Scruffs", "Isn't It a Pity" and "Run of the Mill" resonated with listeners as documents of the group's dysfunction.[249] In the fallout to the break-up, according to journalist Kitty Empire, Harrison's triple album "functioned as a kind of repository for grief" for the band's fans.[250]

Commercial performance

edit"My Sweet Lord" was highly successful,[242] topping singles charts around the world during the first few months of 1971.[73] It was the first solo single by a former Beatle to be number 1 in the UK or the US,[251] and became the most performed song of that year.[252][nb 22] Issued in February 1971, the second single, "What Is Life" backed with "Apple Scruffs",[254] also became an international hit.[255]

All Things Must Pass was number 1 on the UK's official albums chart for eight weeks, although until 2006, chart records incorrectly stated that it had peaked at number 4.[256][nb 23] On Melody Maker's national chart, the album was also number 1 for eight weeks, from 6 February to 27 March, six of which coincided with "My Sweet Lord" topping the magazine's singles chart.[257] In America, All Things Must Pass spent seven weeks at number 1 on the Billboard Top LP's chart, from 2 January until 20 February, and a similarly long period atop the listings compiled by Cash Box and Record World;[258] for three of those weeks, "My Sweet Lord" held the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100.[259] In Canada the album hit number 1 on just its 3rd week, was number 1 for 9 weeks, and was on the charts for 31 weeks, ending July 17, 1971.[260]

The extent of Harrison's success surprised the music industry and largely overshadowed Lennon's concurrently released Plastic Ono Band album, which Spector also co-produced.[261][nb 24] Writing in the April 2001 issue of Record Collector, Peter Doggett described Harrison as "arguably the most successful rock star on the planet" at the start of 1971, with All Things Must Pass "easily outstripping other solo Beatles projects later in the year, such as [McCartney's] Ram and [Lennon's] Imagine".[263] Harrison's so-called "Billboard double" – whereby one artist simultaneously holds the top positions on the magazine's albums and singles listings – was a feat that none of his former bandmates equalled until Paul McCartney and Wings repeated the achievement in June 1973.[264][nb 25] At the 1972 Grammy Awards, All Things Must Pass was nominated for Album of the Year and "My Sweet Lord" for Record of the Year, but Harrison lost out in both categories to Carole King.[266][267]

All Things Must Pass was awarded a gold disc by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) on 17 December 1970[268] and it has since been certified seven times platinum by the RIAA.[258][269] In January 1975, the Canadian Recording Industry Association announced that it had been certified as a platinum album in Canada.[270][nb 26] According to John Bergstrom of PopMatters, as of January 2011, All Things Must Pass had sold more than Imagine and McCartney and Wings' Band on the Run (1973) combined.[272] Also writing in 2011, Lennon and Harrison biographer Gary Tillery describes it as "the most successful album ever released by an ex-Beatle".[273] According to Hamish Champ's 2018 book The 100 Best-Selling Albums of the 70s, in the US, All Things Must Pass is the 33rd-best-selling album from the 1970s.[274]

Critical reception

editContemporary reviews

editAll Things Must Pass received almost universal critical acclaim on release[275] – as much for the music and lyrical content as for the fact that, of all the former Beatles, it was the work of supposed junior partner George Harrison.[3][225][276] Harrison had usually contributed just two songs to a Beatles album;[277] in author Robert Rodriguez's description, critics' attention was now centred on "a major talent unleashed, one who'd been hidden in plain sight all those years" behind Lennon and McCartney. "That the Quiet Beatle was capable of such range", Rodriguez continues, "from the joyful 'What Is Life' to the meditative 'Isn't It a Pity' to the steamrolling 'Art of Dying' to the playful 'I Dig Love' – was revelatory."[278] Most reviewers tended to discount the third disc of studio jams, accepting that it was a "free" addition to justify the set's high retail price,[89][142] although Anthony DeCurtis recognises Apple Jam as further evidence of the album's "bracing air of creative liberation".[279][nb 27]

Ben Gerson of Rolling Stone deemed All Things Must Pass "both an intensely personal statement and a grandiose gesture, a triumph over artistic modesty"[2] and referenced the three-record set as an "extravaganza of piety and sacrifice and joy, whose sheer magnitude and ambition may dub it the War and Peace of rock 'n' roll".[281] Gerson also lauded the album's production as being "of classic Spectorian proportions, Wagnerian, Brucknerian, the music of mountain tops and vast horizons".[2][282] In the NME, Alan Smith referred to Harrison's songs as "music of the mind", adding: "they search and they wander, as if in the soft rhythms of a dream, and in the end he has set them to words which are often both profound and profoundly beautiful."[97] Billboard's reviewer hailed All Things Must Pass as "a masterful blend of rock and piety, technical brilliance and mystic mood, and relief from the tedium of everyday rock".[283]

Melody Maker's Richard Williams summed up the surprise many felt at Harrison's apparent transformation: All Things Must Pass, he said, provided "the rock equivalent of the shock felt by pre-war moviegoers when Garbo first opened her mouth in a talkie: Garbo talks! – Harrison is free!"[3] In another review, for The Times, Williams opined that, of all the Beatles' solo releases thus far, Harrison's album "makes far and away the best listening, perhaps because it is the one which most nearly continues the tradition they began eight years ago".[276][nb 28] William Bender of Time magazine described it as an "expressive, classically executed personal statement ... one of the outstanding rock albums in years", while Tom Zito of The Washington Post predicted that it would influence the discourse on "the [real] genius behind the Beatles".[286]

In The New York Times, Don Heckman deemed the album "a release that shouldn't be missed"[286] and outlined his "complex" reaction to being presented with a sequence of Harrison songs for the first time: "amazement at the range of Harrison's talents; fascination at the effects of Phil Spector's participation as the album's producer; curiosity about the many messages that waft through the Harrison songs".[287] John Gabree of High Fidelity described it as "the big album of the year" and a "unified yet tremendously varied" work. In response to rumours that the Beatles were due to reunite, Gabree said that, on the strength of the Harrison and Lennon solo albums, "I, for one, don't care if they ever do."[288]

Retrospective assessments

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [46] |

| Blender | [289] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [290] |

| Mojo | [226] |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[291] |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[292] |

| Q | [293] |

| Rolling Stone | [279] |

| Uncut | [294] |

An album that sounded contemporary in 1970 was viewed as dated and faddish later in the decade.[141] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau, having bemoaned in 1971 that it was characterised by "overblown fatuity" and uninteresting music,[295] wrote in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981) of the album's "featurelessness", "right down to the anonymity of the multitracked vocals".[296] In their book The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Roy Carr and Tony Tyler were likewise lukewarm in their assessment, criticising the "homogeneity" of the production and "the lugubrious nature of Harrison's composing".[142] Writing in The Beatles Forever in 1977, however, Nicholas Schaffner praised the album as the "crowning glory" of Harrison's and Spector's careers, and highlighted "All Things Must Pass" and "Beware of Darkness" as the "two most eloquent songs ... musically as well as lyrically".[297]

AllMusic's Richie Unterberger views All Things Must Pass as "[Harrison's] best ... a very moving work",[46] and Roger Catlin of MusicHound describes the set as "epic and audacious", its "dense production and rich songs topped off by the extra album of jamming".[291] Unterberger has also written that while the Beatles' break-up remains a source of sorrow for many listeners, "it's impossible not to rejoice in George's greatest triumph" and that, as further evidenced in the bootlegs of outtakes from the sessions, Lennon, McCartney and Beatles producer George Martin undervalued not just Harrison's songwriting abilities but also his talent as a producer.[298] Q magazine considers the album to be an exemplary fusion of "rock and religion", as well as "the single most satisfying collection of any solo Beatle".[293] Filmmaker Martin Scorsese has written of the "powerful sense of the ritualistic on the album", adding: "I remember feeling that it had the grandeur of liturgical music, of the bells used in Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies."[299] Writing for Rolling Stone in 2002, Greg Kot described this grandeur as an "echo-laden cathedral of rock in excelsis" where the "real stars" are Harrison's songs;[54] in the same publication, Mikal Gilmore labelled the album "the finest solo work any ex-Beatle ever produced".[300]

In his 2001 review for Mojo, John Harris said that All Things Must Pass "remains the best Beatles solo album ... oozing both the goggle-eyed joy of creative emancipation and the sense of someone pushing himself to the limit".[301] In another 2001 review, for the Chicago Tribune, Kot wrote: "Neither Lennon nor McCartney, let alone Ringo Starr, ever put out a solo album more accomplished than All Things Must Pass ... In subsequent years, Lennon and McCartney would strive mightily to scale the same heights as All Things Must Pass with solo works such as Imagine and Band on the Run, but they would never top it."[302][nb 29] Nigel Williamson of Uncut said that the album includes some of Harrison's best songs in "My Sweet Lord", "All Things Must Pass" and "Beware of Darkness", and stands as "George's finest ... and arguably the best post-Beatles solo album of them all".[294]

In The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), Mac Randall writes that the album is exceptional, but "a tad overrated" by those critics who tend to overlook how its last 30 minutes comprise "a bunch of instrumental blues jams that nobody listens to more than once".[303] Unterberger similarly cites the inclusion of Apple Jam as "a very significant flaw", while recognising that its content "proved to be of immense musical importance", with the formation of Derek and the Dominos.[46] Writing for Pitchfork in 2016, Jayson Greene said that Harrison was the only former Beatle who "changed the terms of what an album could be" since, although All Things Must Pass was not the first rock triple LP, "in the cultural imagination, it is the first triple album, the first one released as a pointed statement."[292]

Legacy

editGeorge Harrison confronted the breakup head-on, with the graceful, philosophical All Things Must Pass. A series of elegies, dream sequences, and thoughts on the limits of idealism, it is arguably the most fully realized solo statement from any of the Beatles.[304]

– Music critic Tom Moon, in 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die (2008)

Author Mark Ribowsky says that All Things Must Pass "forged the seventies first new rock idiom",[305] while music historian David Howard writes that the album's combination of expansive hard rock and "intimate acoustic-confessionals" made it the touchstone for the early 1970s rock sound.[306] Another Rolling Stone critic, James Hunter, commented in 2001 on how All Things Must Pass "helped define the decade it ushered in", in that "the cast, the length, the long hair falling on suede-covered shoulders ... foretold the sprawl and sleepy ambition of the Seventies."[307]

In his PopMatters review, John Bergstrom likens All Things Must Pass to "the sound of Harrison exhaling", adding: "He was quite possibly the only Beatle who was completely satisfied with the Beatles being gone."[272] Bergstrom credits the album with heavily influencing bands such as ELO, My Morning Jacket, Fleet Foxes and Grizzly Bear, as well as helping bring about the dream pop phenomenon.[272] In Harris' view, the "widescreen sound" used by Harrison and Spector on some of the tracks was a forerunner to recordings by ELO and Oasis.[308]

Among Harrison's biographers, Simon Leng views All Things Must Pass as a "paradox of an album": as eager as Harrison was to break free from his identity as a Beatle, Leng suggests, many of the songs document the "Kafkaesque chain of events" of life within the band and so added to the "mythologized history" he was looking to escape.[309] Ian Inglis notes 1970's place in an era marking "the new supremacy of the singer-songwriter", through such memorable albums as Simon & Garfunkel's Bridge Over Troubled Water, Neil Young's After the Gold Rush, Van Morrison's Moondance and Joni Mitchell's Ladies of the Canyon, but that none of these "possessed the startling impact" of All Things Must Pass.[310] Harrison's triple album, Inglis writes, "[would] elevate 'the third Beatle' into a position that, for a time at least, comfortably eclipsed that of his former bandmates".[310]

Writing for Spectrum Culture, Kevin Korber describes the album as a celebration of "the power that music and art can have if we are free to create it and experience it on our own terms", and therefore "perhaps the greatest thing to come out of the breakup of the Beatles".[311] Jim Irvin considers it to be "a sharper clutch of songs than Imagine, more individual than Band on the Run" and concludes, "It's hard to think of many bigger-hearted, more human and more welcoming records than this."[88]

All Things Must Pass features in music reference books such as The Mojo Collection: The Greatest Albums of All Time,[312] Robert Dimery's 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[313] and Tom Moon's 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die.[314] In 1999, All Things Must Pass appeared at number 9 on The Guardian's "Alternative Top 100 Albums" list, where the editor described it as the "best, mellowest and most sophisticated" of all the Beatles' solo efforts.[315] In 2006, Pitchfork placed it at number 82 on the site's "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s".[84] It was ranked 433rd on Rolling Stone's list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" in 2012[316] and 368th on the 2020 updated list.[317] All Things Must Pass has also appeared in the following critics' best-album books and lists, among others: the Paul Gambaccini-compiled Critic's Choice: Top 200 Albums (1978; ranked number 79),[citation needed] The Times' "100 Best Albums of All Time" (1993; number 79),[citation needed] Allan Kozinn's The 100 Greatest Pop Albums of the Century (published in 2000),[citation needed] Q's "The 50 (+50) Best British Albums Ever" (2004),[citation needed] Mojo's "70 of the Greatest Albums of the 70s" (2006),[citation needed] the NME's "100 Greatest British Albums Ever" (2006; number 86),[citation needed] Paste magazine's "The 70 Best Albums of the 1970s" (2012; number 27),[citation needed] and Craig Mathieson and Toby Creswell's The 100 Best Albums of All Time (2013).[318]

In January 2014, All Things Must Pass was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame,[319] an award bestowed by the Recording Academy "to honor recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance that are at least 25 years old".[320] Colin Hanks titled his 2015 film All Things Must Pass: The Rise and Fall of Tower Records after the album and, with the blessing of Harrison's widow, Olivia Harrison, used the title track over the end credits.[262]

Subsequent releases

edit2001

editTo mark the 30th anniversary of the album's release, Harrison supervised a remastered edition of All Things Must Pass, which was issued in January 2001, less than a year before his death from cancer at the age of 58.[321][nb 30] Ken Scott engineered the reissue,[323] which was remastered by Jon Astley.[324] Harrison and Scott were shocked at the amount of reverb they had used in 1970[325] and were keen to remix the album, but EMI vetoed the idea.[212]

The reissue appeared on Gnome Records, a label set up by Harrison for the project.[326] Harrison also oversaw revisions to Wilkes and Feinstein's album artwork,[149] which included a colourised "George & the Gnomes" front cover[149] and, on the two CD sleeves and the album booklet, further examples of this cover image showing an imaginary, gradual encroachment of urbanisation on the Friar Park landscape.[94][nb 31] The latter series served to illustrate Harrison's dismay at "the direction the world seemed headed at the start of the millennium", Gary Tillery observes, a direction that was "so far afield from the Age of Aquarius that had been the dream of the sixties".[327][nb 32] Harrison launched a website dedicated to the reissue, which offered, in the description of Chuck Miller of Goldmine magazine, "graphics and sounds and little Macromedia-created gnomes dancing and giggling and playing guitars in a Terry Gilliam-esque world".[329]

Titled All Things Must Pass: 30th Anniversary Edition, the new album contained five bonus tracks, including "I Live for You",[330] two of the songs performed for Spector at EMI Studios in May 1970 ("Beware of Darkness" and "Let It Down") and "My Sweet Lord (2000)", a partial re-recording of Harrison's biggest solo hit.[331] In addition, Harrison resequenced the content of Apple Jam so that the album closed with "Out of the Blue", as he had originally intended.[93][149] Assisting Harrison with overdubs on the bonus tracks were his son, Dhani Harrison, singer Sam Brown and percussionist Ray Cooper,[93] all of whom contributed to the recording of Brainwashed around this time.[332] According to Scott, Harrison had suggested they include a bonus disc containing recollections from some of the album's contributors, starting with Ringo Starr. The idea was abandoned since Starr could not remember playing on the sessions at all.[212]

With Harrison undertaking extensive promotional work, the 2001 reissue was a critical and commercial success.[333] Having underestimated the album's popularity, Capitol faced a back order of 20,000 copies in America.[334] There, the reissue debuted at number 4 on Billboard's Top Pop Catalog Albums chart[335] and topped the magazine's Internet Album Sales listings.[336] In the UK, it peaked at number 68 on the national albums chart.[337] Writing in Record Collector, Doggett described this success as "a previously unheard-of achievement for a reissue".[338]

Following Harrison's death on 29 November 2001, All Things Must Pass returned to the US charts, climbing to number 6 and number 7, respectively, on the Top Pop Catalog and Internet Album Sales charts.[339] With the release on iTunes of much of the Harrison catalogue, in October 2007,[340] the album re-entered the US Top Pop Catalog chart, peaking at number 3.[341]

2010

editFor the 40th anniversary of All Things Must Pass, EMI reissued the album in its original configuration, in a limited-edition box set of three vinyl LPs, on 26 November 2010.[342][343] Each copy was individually numbered.[344][345] In what Bergstrom views as a contrast with the more aggressive marketing campaign run simultaneously by John Lennon's estate, to commemorate Lennon's 70th birthday,[272] a digitally remastered 24-bit version of the album was made available for download from Harrison's official website.[342][343] The reissue coincided with the Harrison estate's similarly low-key[346] release of the Ravi Shankar–George Harrison box set Collaborations[347] and East Meets West Music's reissue of Raga, the long-unavailable documentary on Shankar that Harrison had helped release through Apple Films in 1971.[348][349]

2014

editAll Things Must Pass was remastered again for the eight-disc Harrison box set The Apple Years 1968–75,[350] issued in September 2014.[351] Also available as a separate, double-CD release, the reissue reproduces Harrison's 2001 liner notes[352] and includes the same five bonus tracks that appeared on the 30th anniversary edition.[350] In addition, the box set's DVD contains the promotional film created for the 2001 reissue.[353]

2020–2021

editOn 27 November 2020, the Harrison family released a stereo remix of the song "All Things Must Pass" to mark the album's 50th anniversary. Dhani Harrison described it as a prelude to further releases related to the anniversary.[354] That same month, as part of its Archive on 4 series, BBC Radio 4 broadcast "All Things Must Pass at 50", a one-hour special presented by Nitin Sawhney.[355]

On 10 June 2021, the release of a 50th anniversary edition was officially announced for 6 August.[356] The reissue is available in seven varieties, from Standard vinyl and CD editions up to an Uber Deluxe Edition box set.[357] The most extensive editions contain 70 tracks across 5 CDs/8LPs, including outtakes, jams and 47 demos, 42 of which are previously unreleased,[358] and a scrapbook containing archival notes and track-by-track annotation curated by Olivia Harrison.[357] The Uber Deluxe set adds a 44-page book on the creation of the 1970 triple album,[356] along with scale replica figurines of Harrison and the Friar Park gnomes, an illustration by Voormann, and Paramahansa Yogananda's text "Light from the Great Ones", among other extras.[357]

On Metacritic, the Super Deluxe Edition has an aggregate score of 92 out of 100, based on eight reviews – indicating what the website defines as "universal acclaim".[359] The release received maximum scores from Mojo, The Times, The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, Uncut and American Songwriter.[360] It peaked at number 6 in the UK and number 7 on the Billboard 200 in the US; in other Billboard charts, it topped the listings for Top Rock Albums, Catalog Albums and Tastemaker Albums, and placed at number 2 on Top Albums Sales. The 50th anniversary release also peaked at number 2 in Germany and number 3 in Switzerland, among other top-ten international chart placings.[360] In 2022, the 50th anniversary box set won the Grammy Award for Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package.[361]

Track listing

editAll songs written by George Harrison, except where noted.

Original release

editSide one

- "I'd Have You Anytime" (Harrison, Bob Dylan) – 2:56

- "My Sweet Lord" – 4:38

- "Wah-Wah" – 5:35

- "Isn't It a Pity (Version One)" – 7:10

Side two

- "What Is Life" – 4:22

- "If Not for You" (Dylan) – 3:29

- "Behind That Locked Door" – 3:05

- "Let It Down" – 4:57

- "Run of the Mill" – 2:49

Side three

- "Beware of Darkness" – 3:48

- "Apple Scruffs" – 3:04

- "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)" – 3:48

- "Awaiting on You All" – 2:45

- "All Things Must Pass" – 3:44

Side four

- "I Dig Love" – 4:55

- "Art of Dying" – 3:37

- "Isn't It a Pity (Version Two)" – 4:45

- "Hear Me Lord" – 5:46

Side five (Apple Jam)

- "Out of the Blue" – 11:14

- "It's Johnny's Birthday" (Bill Martin, Phil Coulter, Harrison) – 0:49

- "Plug Me In" – 3:18

Side six (Apple Jam)

- "I Remember Jeep" – 8:07

- "Thanks for the Pepperoni" – 5:31

2001 remaster

editDisc one

Sides one and two were combined as tracks 1–9, with the following additional tracks:

- "I Live for You" – 3:35

- "Beware of Darkness" (acoustic demo) – 3:19

- "Let It Down" (alternate version) – 3:54

- "What Is Life" (backing track/alternate mix) – 4:27

- "My Sweet Lord (2000)" – 4:57

Disc two

Sides three and four were combined as tracks 1–9, followed by the reordered Apple Jam tracks.

- "It's Johnny's Birthday" (Martin, Coulter, Harrison) – 0:49

- "Plug Me In" – 3:18

- "I Remember Jeep" – 8:07

- "Thanks for the Pepperoni" – 5:31

- "Out of the Blue" – 11:16

2021 50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Box

editDisc one – Remixed (2020) versions of sides 1 and 2.

Disc two – Remixed (2020) versions of sides 3 and 4, remastered versions of sides 5 and 6.

Disc three

- "All Things Must Pass" (Day 1 Demo) – 4:38

- "Behind That Locked Door" (Day 1 Demo) – 2:54

- "I Live for You" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:26

- "Apple Scruffs" (Day 1 Demo) – 2:48

- "What Is Life" (Day 1 Demo) – 4:46

- "Awaiting on You All" (Day 1 Demo) – 2:30

- "Isn't It a Pity" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:19

- "I'd Have You Anytime" (Day 1 Demo) (Harrison, Dylan) – 2:10

- "I Dig Love" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:35

- "Going Down to Golders Green" (Day 1 Demo) – 2:24

- "Dehra Dun" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:39

- "Om Hare Om (Gopala Krishna)" (Day 1 Demo) – 5:13

- "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:41

- "My Sweet Lord" (Day 1 Demo) – 3:21

- "Sour Milk Sea" (Day 1 Demo) – 2:28

Disc four

- "Run of the Mill" (Day 2 Demo) – 1:54

- "Art of Dying" (Day 2 Demo) – 3:04

- "Everybody-Nobody" (Day 2 Demo) – 2:20

- "Wah-Wah" (Day 2 Demo) – 4:24

- "Window Window" (Day 2 Demo) – 1:53

- "Beautiful Girl" (Day 2 Demo) – 2:39

- "Beware of Darkness" (Day 2 Demo) – 3:20

- "Let It Down" (Day 2 Demo) – 3:57

- "Tell Me What Has Happened to You" (Day 2 Demo) – 2:57

- "Hear Me Lord" (Day 2 Demo) – 4:57

- "Nowhere to Go" (Day 2 Demo) (Harrison, Dylan) – 2:44

- "Cosmic Empire" (Day 2 Demo) – 2:12

- "Mother Divine" (Day 2 Demo) – 2:45

- "I Don't Want to Do It" (Day 2 Demo) (Dylan) – 2:05

- "If Not for You" (Day 2 Demo) (Dylan) – 1:48

Disc five

- "Isn't It a Pity" (take 14) – 0:53

- "Wah-Wah" (take 1) – 5:56

- "I'd Have You Anytime" (take 5) (Harrison, Dylan) – 2:48

- "Art of Dying" (take 1) – 2:48

- "Isn't It a Pity" (take 27) – 4:01

- "If Not For You" (take 2) (Dylan) – 2:59

- "Wedding Bells (Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine)" (take 1) (Sammy Fain, Irving Kahal, Willie Raskin) – 1:56

- "What Is Life" (take 1) – 4:34

- "Beware of Darkness" (take 8) – 3:48

- "Hear Me Lord" (take 5) – 9:31

- "Let It Down" (take 1) – 4:13

- "Run of the Mill" (take 36) – 2:28

- "Down to the River (Rocking Chair Jam)" (take 1) – 2:30

- "Get Back" (take 1) (John Lennon, Paul McCartney) – 2:07

- "Almost 12 Bar Honky Tonk" (take 1) – 8:34

- "It's Johnny's Birthday" (take 1) (Martin, Coulter, Harrison) – 0:59

- "Woman Don't You Cry for Me" (take 5) – 5:01

Personnel

editThe following musicians are either credited on the 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass[323] or are acknowledged as having contributed after subsequent research:[362]

- George Harrison – vocals, electric and acoustic guitars, Dobro, harmonica, Moog synthesizer, harmonium, backing vocals; bass guitar (2001 reissue only)

- Eric Clapton – electric and acoustic guitars, backing vocals

- Gary Wright – piano, organ, electric piano

- Bobby Whitlock – organ, harmonium, piano, tubular bells,[363] backing vocals

- Klaus Voormann – bass guitar, electric guitar on "Out of the Blue"[nb 33]

- Jim Gordon – drums

- Carl Radle – bass guitar

- Ringo Starr – drums, percussion

- Billy Preston – organ, piano

- Jim Price – trumpet, trombone

- Bobby Keys – saxophones

- Alan White – drums, vibraphone

- Pete Drake – pedal steel

- John Barham – orchestral arrangements, choral arrangement,[365] harmonium, vibraphone

- Pete Ham – acoustic guitar

- Tom Evans – acoustic guitar

- Joey Molland – acoustic guitar

- Mike Gibbins – percussion

- Peter Frampton – acoustic guitar[134]

- Dave Mason – electric and acoustic guitars

- Tony Ashton – piano

- Gary Brooker – piano

- Mal Evans – percussion, vocal on "It's Johnny's Birthday", "tea and sympathy"

- Ginger Baker – drums on "I Remember Jeep"

- John Lennon – handclaps on "I Remember Jeep"

- Yoko Ono – handclaps on "I Remember Jeep"

- Al Aronowitz – unspecified contribution on "Out of the Blue"

- Eddie Klein – vocal on "It's Johnny's Birthday"

- Dhani Harrison – acoustic guitar, electric piano, backing vocals (2001 reissue only)

- Sam Brown – vocals, backing vocals (2001 reissue only)

- Ray Cooper – percussion, synthesizer (2001 reissue only)

Accolades

editGrammy Awards

edit| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | All Things Must Pass | Album of the Year[266] | Nominated |

| "My Sweet Lord" | Record of the Year[266] | Nominated | |

| 2014 | All Things Must Pass | Hall of Fame Award[320] | Won |

| 2022 | All Things Must Pass | Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package[366] | Won |

Charts

editWeekly charts

editYear-end charts

edit| Chart (1971) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Kent Music Report[368] | 5 |

| Dutch Albums Chart[397] | 11 |

| US Billboard Year-End[398] | 18 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[399] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[400] | Gold | 10,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[401] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[402] | 7× Platinum | 7,000,000‡ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

edit- ^ In conversation with Lennon, Harrison remarked that he already had enough compositions for the next ten years of Beatle releases,[30] given his usual quota of two tracks per album[31][32] and the occasional B-side.[29]

- ^ This is a view held by biographers Leng[44] and Joshua Greene[45] also, as well as by music critics John Harris,[5] David Fricke[43] and Richie Unterberger.[46]

- ^ "Isn't It a Pity" was another song passed over during these sessions,[56] having similarly been turned down, by Lennon,[57] for inclusion on the Beatles' Revolver album (1966).[58]

- ^ Soon after the tour, Harrison gave "My Sweet Lord" and "All Things Must Pass" to Preston,[69] who released the songs on his Encouraging Words album in September 1970, two months before Harrison's versions appeared.[70]

- ^ The face label on each side of disc three contained a jam jar painted by designer Tom Wilkes, showing a piece of fruit inside the jar and two apple leaves on the outside.[94]

- ^ In other interviews, Harrison similarly likened his situation to being "constipated for years" artistically while in the Beatles.[99]

- ^ Frampton said this was because "Spector always wanted 'more acoustics, more acoustics!'"[135] In a 2014 interview, Mason said he could not remember which tracks he played on, but that his contributions were confined to acoustic rhythm guitar.[136]

- ^ Like Barham, Tony Ashton had been a significant contributor to Harrison's Wonderwall Music album.[139] In March 1970, Harrison and Clapton participated in the recording of "I'm Your Spiritual Breadman" by Ashton's new band, Ashton, Gardner and Dyke.[140]

- ^ For similar reasons regarding record companies being "possessive"[144] of their artists,[145] the musician credits on Cream's Goodbye album (1969),[146] Jack Bruce's Songs for a Tailor (1969) and Delaney & Bonnie's On Tour (1970)[147] could only list Harrison under a pseudonym, "L'Angelo Misterioso".[148]

- ^ In his liner notes accompanying the 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass, however, Harrison gives the date for the run-through as 27 May.[158][159]

- ^ Citing Wright's description that Harrison created a "profoundly peaceful" mood in the studio that complemented the quality of the musicianship, musicologist Thomas MacFarlane likens the atmosphere to the sessions for Harrison's Indian-style recordings for the Beatles, such as "Within You Without You".[48]

- ^ Drake also played on the bootlegged instrumental "Pete Drake and His Amazing Talking Guitar",[173] before returning to Nashville to gather material for Starr's country album, Beaucoups of Blues,[174] sessions for which began in the last week of June.[175] Drake's visit to London also impacted on Frampton's career, as he went on to adopt Drake's talking-box guitar effect.[176][177]

- ^ Keys adds that it was only when they started working on Harrison's album that he and Price realised they were not going to join the other Friends personnel in Derek and the Dominos.[191]

- ^ Barham commented that Spector was aloof and distant with the musicians, and his authoritarian tendencies contrasted sharply with Harrison's preference for letting the players find themselves in each song. According to Molland, recalling the "Wah-Wah" playback, Spector "was hitting the Courvoisier pretty hard" even by early afternoon, but: "He was still Phil Spector ... the sound was incredible."[202]

- ^ This personal tragedy was the inspiration for a new Harrison composition, the 1971 B-side "Deep Blue".[204][205]

- ^ Clapton's feelings for Boyd inspired many of his songs on Derek and the Dominos' only studio album, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970).[145] After Boyd rejected him in November 1970, Clapton descended into full-blown heroin addiction,[206] which led to the break-up of the band in early 1971 and the sidelining of his career until 1974.[207]

- ^ Leckie says that some of the overdubbing took place at EMI. He recalls working with McDonald as Harrison added his lead vocal to "Awaiting on You All", by which point the horns and other overdubs were already in place.[208]

- ^ Lennon was recording his song "Remember" in one of the other studios there, with Starr and Voormann. The session tapes reveal Lennon's delight at Harrison's arrival.[217]

- ^ The albums were released, respectively, as Bobby Whitlock (1972), Footprint (1971), Straight Up (1971) and Bobby Keys (1972).[221] Harrison also introduced Badfinger on stage before their opening night at Urgano's in New York City in November 1970.[222][223]

- ^ According to Harrison's recollection in a 1977 interview for Crawdaddy magazine,[200] Lennon first saw the artwork at Friar Park and remarked to a mutual friend of theirs that Harrison "must be fucking mad" to be releasing a triple album, and described him as "look[ing] like an asthmatic Leon Russell" on the cover.[235] Later, in what author Alan Clayson views as a case of "needling Paul rather than praising George",[236] Lennon told Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner that he "preferred" All Things Must Pass to the "rubbish" on McCartney.[237]

- ^ Part of this original poster was a painting of a bathing scene featuring naked women (one of whom was blonde, representing Pattie Boyd) and a "mischievous" Lord Krishna, who had hidden the bathers' clothing in the branches of a nearby tree.[91]

- ^ Aside from the popularity of Harrison's recording, the song attracted a large number of cover versions in 1971.[252] The widespread success of "My Sweet Lord" worked against Harrison when a near-bankrupt music publisher, Bright Tunes, pursued an ultimately successful claim of plagiarism against him in the US district court, for unauthorised copyright infringement of the 1963 song "He's So Fine".[253]

- ^ This error was due to a postal strike in Britain during February and March of 1971, when the national chart compiler failed to receive any sales data from retailers.[256] In July 2006, the Official UK Charts Company changed its records to show that All Things Must Pass was the top-selling album throughout that time.[256]

- ^ Record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, formerly the Rolling Stones' manager, recalls: "When All Things Must Pass came out I sat down and listened to it for three days. It was the first album that sounded like one single."[262]

- ^ Immediately after Wings' success, Harrison again held both number 1 positions, with his "Give Me Love" single and its parent album, Living in the Material World.[264][265]

- ^ Capitol Canada executives presented Harrison with the platinum award in Toronto in December 1974, shortly before he performed at the city's Maple Leaf Gardens.[271]

- ^ Previewing the LP in the Detroit Free Press, Mike Gormley said that Apple Jam constituted "some exceptional hard rock and roll". He concluded: "The album should sell for around $10. It's worth $50."[280]

- ^ Aside from non-vocal albums such as Harrison's Wonderwall Music and Electronic Sound, and Lennon's experimental work with Ono, beginning with Two Virgins (1968),[284] the solo albums up to January 1971 were as follows: Lennon's Live Peace in Toronto (1969), Starr's Sentimental Journey (1970), McCartney, Beaucoups of Blues, All Things Must Pass and John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.[285]

- ^ Mick Brown, writing in The Daily Telegraph, also considers it the best of all the Beatles' solo albums.[196]

- ^ EMI had scheduled the release for 21 November 2000, close to the true date for the anniversary, but the album was delayed for two months.[322]

- ^ In Britain, Gnome/EMI released the remastered album on vinyl also, the packaging for which contained four stages in this pictorial series compared with the three available in the CD box.[94] The revised artwork for All Things Must Pass was credited to WhereforeArt?[94]

- ^ Adding to this ecological message, during promotion for the reissue, Harrison jokingly suggested that the title for his next studio album, the long-awaited follow-up to Cloud Nine (1987), might be Your Planet Is Doomed – Volume One.[328]

- ^ In Leng's book, Voormann states it was him playing lead guitar with Harrison on "Out of the Blue" and not Clapton, as credited by Harrison on the Apple Jam sleeve: "[George] thought it was Eric, because I was playing a little thing like Eric."[364]

References

edit- ^ Moon, p. 346.

- ^ a b c Ben Gerson, "George Harrison All Things Must Pass" Archived 28 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, 21 January 1971, p. 46 (retrieved 5 June 2013).

- ^ a b c Schaffner, p. 140.

- ^ Larkin, p. 2635.

- ^ a b c d Harris, p. 68.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 164.

- ^ Leng, pp. 39, 51–52.

- ^ Tillery, p. 86.

- ^ Leng, p. 39.

- ^ George Harrison, pp. 55, 57–58.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 176, 177, 184–85.

- ^ Leng, pp. 39, 53–54.

- ^ "Artist: Cream", Official Charts Company (retrieved 16 January 2013).

- ^ Sulpy & Schweighardt, pp. 1, 85, 124.

- ^ Martin O'Gorman, "Film on Four", Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970), Emap (London, 2003), p. 73.

- ^ Leng, pp. 39, 55.

- ^ Leng, pp. 60–62, 71–72, 319.

- ^ O'Dell, pp. 106–07.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 1.

- ^ Miles, pp. 351, 360–62.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 206–08, 267.

- ^ Spizer, p. 341.

- ^ Miles, p. 367.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 21.

- ^ George Harrison, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD, Village Roadshow, 2011 (directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese).

- ^ The Beatles, p. 350.

- ^ Spizer, p. 28.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 137–38.

- ^ a b Hertsgaard, p. 283.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spizer, p. 220.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 135.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 68, 87.

- ^ Miles, p. 335.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 38.

- ^ Huntley, p. 19.

- ^ Clayson, p. 285.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 185.

- ^ Tillery, p. 87.

- ^ Clayson, p. 284.

- ^ O'Dell, pp. 155–56.

- ^ Hertsgaard, p. 277.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 180.

- ^ Leng, p. 82.

- ^ Greene, pp. 179, 221.

- ^ a b c d Richie Unterberger, "George Harrison All Things Must Pass", AllMusic (retrieved 28 April 2012).

- ^ a b c Olivia Harrison, p. 282.

- ^ a b MacFarlane, p. 72.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 212, 225.

- ^ Leng, p. 52.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 423.

- ^ Sulpy & Schweighardt, p. 8.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, p. 186.

- ^ a b c The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 187.

- ^ Huntley, p. 21.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 38, 187.

- ^ Sulpy & Schweighardt, p. 269.

- ^ MacDonald, p. 302fn.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Harris, p. 72.

- ^ Leng, p. 85.

- ^ Timothy White, "George Harrison – Reconsidered", Musician, November 1987, p. 55.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 91.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 188.

- ^ Andy Davis, Billy Preston Encouraging Words CD, liner notes (Apple Records, 2010; produced by George Harrison & Billy Preston).

- ^ Clayson, p. 273.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 206.

- ^ a b Harris, p. 70.

- ^ Leng, pp. 67, 71, 88, 89.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 91.

- ^ a b George Harrison, p. 172.

- ^ Allison, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Schaffner, p. 142.

- ^ Inglis, p. 29.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 426, 431.

- ^ Inglis, p. 28.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 198.

- ^ Badman, pp. 6, 7.

- ^ Inglis, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Clayson, p. 297.

- ^ Leng, p. 319.

- ^ Leng, pp. 68, 102.

- ^ Leng, pp. 87, 92, 102, 157.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s", Pitchfork, 23 April 2006 (archived version retrieved 14 October 2014).

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 197.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 53, 56, 61.

- ^ Leng, pp. 76, 86.

- ^ a b Jim Irvin, "George Harrison: All Things Must Pass (Apple)", Rock's Backpages, 2000 (subscription required; retrieved 28 November 2020).

- ^ a b Clayson, p. 292.

- ^ Leng, pp. 101–02.

- ^ a b c d e f Spizer, p. 226.

- ^ Huntley, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Timothy White, "George Harrison: 'All Things' in Good Time", billboard.com, 8 January 2001 (retrieved 3 June 2014).

- ^ a b c d Spizer, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Madinger & Easter, p. 432.

- ^ a b Castleman & Podrazik, p. 94.

- ^ a b Alan Smith, "George Harrison: All Things Must Pass (Apple)", NME, 5 December 1970, p. 2; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 15 July 2012).

- ^ Spizer, p. 230.