Electronic Sound is the second studio album by the English rock musician George Harrison. Released in May 1969, it was the last of two LPs issued on the Beatles' short-lived Zapple record label, a subsidiary of Apple Records that specialised in the avant-garde. The album is an experimental work comprising two lengthy pieces performed on a Moog 3-series synthesizer. It was one of the first electronic music albums by a rock musician, made at a time when the Moog was usually played by dedicated exponents of the technology. Harrison subsequently introduced the Moog to the Beatles' sound, and the band featured synthesizer for the first time on their 1969 album Abbey Road.

| Electronic Sound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 9 May 1969 | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | Avant-garde,[1][2] electronic music[3] | |||

| Length | 43:50 | |||

| Label | Zapple | |||

| Producer | George Harrison | |||

| George Harrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

Harrison began the project in Los Angeles, in November 1968, while he was producing sessions for his Apple Records artist Jackie Lomax. "No Time or Space" comprises an edit of a Moog demonstration given there by Bernie Krause, an American synthesizer exponent and Moog salesman. Once his own Moog system had arrived in England, in February 1969, Harrison recorded the second piece, "Under the Mersey Wall", at his home in Surrey. Krause later said that, with "No Time or Space", Harrison had recorded the studio demonstration without his knowledge and that it incorporated ideas he was due to include on his forthcoming album with Paul Beaver.

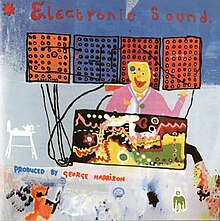

The cover artwork of Electronic Sound was taken from a painting by Harrison. The front cover shows Krause operating the Moog console, while the back depicts Derek Taylor's office at Apple and the pressures afflicting the company at the time.

The album has received an unfavourable response from many rock critics; these writers dismiss it as unfocused, unstructured, and consisting of random sounds. Some commentators and musicians judge it to be an adventurous work that displays the Moog's sonic potential at a time when the system was in its infancy. In the United States and Canada, the LP was pressed with the two tracks swapped around, leading to confusion regarding the identity of the pieces. The order was corrected for the album's CD release in 1996. The 2014 reissue includes essays by Kevin Howlett and electronica musician Tom Rowlands, along with Dhani Harrison's explanation of his father's artwork.

Background

editAlthough a guitarist and, from 1966, an aspiring sitarist under Indian musician Ravi Shankar, George Harrison turned to keyboard instruments as a tool for songwriting in 1967.[4][5] These instruments included Hammond organ on some of his songs with the Beatles, and Mellotron[6][7] on several of the Western selections on his debut solo album, the Wonderwall Music film soundtrack.[8][9] Described by producer George Martin as the most dedicated of the Beatles in finding and creating new sounds for the band's studio recordings,[10] Harrison became intrigued by the potential of the Moog synthesizer while in Los Angeles in late 1968.[11][12] He was introduced to the instrument by Bernie Krause, who, along with his Beaver & Krause partner Paul Beaver, was the Moog company's sales representative for the US West Coast.[13][14][nb 1]

An off-shoot of the Beatles' Apple record label, Zapple Records was intended as an outlet for avant-garde musical works and spoken-word albums.[21][22] The music on Electronic Sound, consisting of two extended instrumental pieces – "Under the Mersey Wall" and "No Time or Space" – was performed on a Moog 3 modular system. Harrison bought the system from the Moog company through Krause, and later had it set up at EMI Studios in London for the Beatles to use on their recordings.[14][23]

In author Alan Clayson's view, the album was Harrison's "gesture of artistic solidarity" towards John Lennon and Yoko Ono, whose experimental collaborations, having first appeared on the Beatles' 1968 track "Revolution 9", made up Zapple's other inaugural album, Life with the Lions.[24][nb 2] In a 1987 interview, Harrison said that Electronic Sound, like the Lennon–Ono album, was an example of Zapple's ethos of "let[ting] serendipity take hold" rather than a formal creative work.[26]

Recording and content

editAll I did was get that very first Moog synthesizer, with the big patch unit and the keyboards that you could never tune, and I put a microphone into a tape machine … So whatever came out when I fiddled with the knobs went on tape – but some amazing sounds did happen.[27]

– George Harrison, 1987

According to the album's liner notes, "No Time or Space" was recorded "in California in November 1968 with the assistance of Bernie Krause".[28] The title was a phrase Harrison had adopted when discussing the aim of Transcendental Meditation in a September 1967 interview for the BBC Radio 1 show Scene and Heard.[29] Krause later said that "No Time or Space" was a recording of him demonstrating the Moog III to Harrison in Los Angeles, following a session for Jackie Lomax's album Is This What You Want?, which Harrison was producing at the time.[30][31] Krause claimed that the demonstration was recorded without his knowledge and nor would he have given his consent, since his playing included ideas he intended to develop on the next Beaver & Krause album. Krause's name was originally included on the front cover of Electronic Sound, under Harrison's, but it was painted over at Krause's insistence.[14] The words "Bernie Krause" were nevertheless visible under the silver ink on original LP pressings.[32][33]

The information for "Under the Mersey Wall" reads: "Recorded at Esher in Merrie England; with the assistance of Rupert and Jostick The Siamese Twins – February 1969."[28] The title of this piece was a play on "Over the Mersey Wall", a column by a newspaper journalist named George Harrison that appeared in The Liverpool Echo.[30][34] Harrison recorded "Under the Mersey Wall" at his house, Kinfauns,[35] after Krause had travelled to England to help him set up the new Moog system.[30]

Costing around $8000 (equivalent to $70,000 in 2023), Harrison's was the 95th synthesizer sold by the Moog company,[36] but only the third to arrive in Britain.[37] At Harrison's request, Krause first persuaded customs officers at Heathrow Airport that the system was a musical instrument and to accept a minimal tariff to release the equipment.[32] Harrison's Moog 3P set-up comprised a pair of five-octave keyboards with portamento control, a ribbon controller, modules including ten voltage-controlled oscillators, a white noise generator, three ADSR envelope generators, voltage-controlled filters and amplifiers, a spring reverberation unit and a four-channel mixer.[38][39]

By 1968, Krause had become disillusioned with working with rock artists and what he saw as their limited view of the Moog's potential.[40] Aside from Krause's discovery that Harrison intended to use the 1968 demonstration piece on the album, the relationship between the two musicians was adversely affected by Harrison's stay in hospital in early February, where he had his tonsils removed. Krause felt insulted by the treatment he received at the Apple Corps headquarters, where the staff had no knowledge of his visit. Krause and his wife then went to Paris, only to be summoned back to London by Harrison once he was released from hospital.[32] Harrison later commented that the Moog had no instruction manual; the falling out between him and Krause meant that Harrison received only basic guidance on how to operate the system.[41][nb 3]

The notes accompanying the track listing on the LP sleeve were taken from a Zapple press release written by Richard DiLello,[44] who served in the position of "house hippy" at Apple.[45] Among DiLello's comments, he described "No Time or Space" as "a pottage of space music" and said of "Under the Mersey Wall": "in a mounting vortex of decibels, there came to pass a wrecked chord of environmental sound that went beyond the genre of hashish cocktail music. The bass line had been milked through the Moog machine and, lo and high, we behold electronic music …"[44] The inside sleeve included a quotation attributed to "Arthur Wax": "There are a lot of people around, making a lot of noise; here's some more."[46]

Artwork

editThe cover of Electronic Sound was painted by Harrison himself.[44] According to Beatles historian Bruce Spizer, the vivid colours and childlike quality of the artwork "add a feeling of lightness" to the austere sounds found on the album.[46] The front cover image includes a green-faced figure holding a green apple in one hand and standing behind a Moog console. The reverse is a scene from Derek Taylor's office at Apple, with the words "Grapple with it" painted above and below a white sofa.[46] At this time, according to author and Zapple manager Barry Miles, the "spectre of Zapple's demise" and Apple's gradual disintegration were already apparent.[47]

Harrison's son Dhani says that the two sleeve images were part of a single large painting, which he discussed with his father after discovering it in the family home, Friar Park, in the 1990s.[48] In Dhani's description, the green man on the front is Krause, who is controlling the Moog and ensuring that sound emanates from the right of the device, in the manner of a meat grinder. Harrison appears as a small blue smiling face below this, "making the tea", while the green shape along the bottom of the image represents Jostick,[48] one of his and Pattie Boyd's Siamese cats.[49]

In the portion used on the back of the LP, according to Dhani, Taylor is seen flying an "angry kite", which represents the aggravation that was pervasive at Apple in 1969, hence the "Grapple with it" message.[nb 4] The faces on Taylor's large wicker chair are Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall,[48][54] the Beatles' longtime assistants and former road managers.[55] Both men were frequently torn in their loyalties towards the individual Beatles, due to the dysfunction within the band during the Apple era;[56] the cover shows Evans smiling and Aspinall wearing a frown with, in Miles' words, "all the cares of Apple on his shoulders".[54] Harrison's friend Eric Clapton is pictured with a Hendrix-style afro and in psychedelic attire,[57] and holding a guitar.[48] As further examples of the inharmonious atmosphere at Apple, Miles notes that, unlike the four portraits of the Beatles hanging on the office wall, a picture of an Indian yogi with the Om symbol above him is upside down, and so too is the view through the office window in the top right corner of the image.[57]

Author Mark Brend describes the cover art as "a twist on the convention of making the instrument itself a focus", since the four Moog modules appear to be grouped together behind the synthesizer player as if they are his backing musicians.[58]

Release

editElectronic Sound was released on Zapple Records on 9 May 1969 in the UK and on 26 May in the United States.[59][60] In the UK, the album's catalogue number was Zapple 02, indicating it as the second LP on the label after Lennon and Ono's Life with the Lions.[61][62] Unlike Harrison, Lennon and Ono promoted their new album extensively on UK radio. During their interview for Radio Luxembourg, Lennon also gave a plug for Electronic Sound when stating that atmosphere and sound were now of more interest to him than melody and words.[63]

According to Beatles biographer Nicholas Schaffner, both albums confused and proved "virtually unlistenable" to the majority of record buyers, and Zapple's claim that it was a label producing "paperback records" was not borne out in the high retail price of the LPs in the US.[64][nb 5] Electronic Sound was sullied further after Krause wrote to Rolling Stone magazine complaining of Harrison's appropriation of his demonstration piece and saying that he was "frankly hurt and a bit disillusioned by the whole thing".[66] Electronic Sound failed to chart in the United Kingdom,[34] while in the United States, it peaked at number 191 during its two weeks on the Billboard Top LPs chart.[67] As one of the first measures initiated by Allen Klein, the new manager of Apple Corps, the Zapple label was shut down shortly after the album's release.[68][69] Electronic Sound and Life with the Lions were deleted and soon became highly prized among collectors.[70]

On the original United States and Canada pressings of Electronic Sound, the order of the recordings was accidentally switched, although the titles were not.[32][71] This mistake caused many listeners to confuse the two pieces.[28] The album was issued on CD for the first time in December 1996, in the UK and Japan only,[72] at which point the correct running order was used.[73] Harrison was highly dismissive of Electronic Sound and Life with the Lions at this time.[74] Rather than include the planned 1000-word liner note essay in the CD booklet for his album, he supplied his own text, reading simply: "It could be called avant-garde, but a more apt description would be (in the words of my old friend Alvin), 'Avant Garde Clue'!"[75]

Electronic Sound was reissued in remastered CD form on 22 September 2014, as part of the Apple Years 1968–75 Harrison box set.[28] The album was also made available as a high-resolution 24-bit 96 kHz digital download. The Moog 3P synthesizer used by Harrison on the album is still owned by the Harrison family and is pictured in the centre photo spread of the 2014 CD reissue. Dhani Harrison supplied an essay in the CD booklet[76] in which he recalls his father's explanation of the cover painting.[77]

Critical reception

editContemporary reviews

editAllen Evans of the NME described the record as "for intellectuals, a rare LP for 'reading into it' something that probably isn't there". He found little meaning in the combination of mechanical sounds on "No Time or Space" and said that "Under the Mersey Wall" was more musical, with a semblance of form revealing itself after an opening that he likened to "someone learning an instrument".[78] Melody Maker compared Electronic Sound favourably with Wendy Carlos's Moog album Switched-On Bach, which became a surprise commercial hit after entering the Billboard Top LPs chart in March.[79] The writer said that Harrison's work was superior because, unlike the Carlos LP, "it never tries to reproduce sounds produced originally by humans. That is the way [electronic music] must go."[58]

In his joint review of Electronic Sound and Life with the Lions, Ed Ward of Rolling Stone dismissed the Lennons' album as "utter bullshit"[21] and said that Harrison had "done quite well learning his way around his new Moog Synthesizer ... but he's still got a way to go". Ward added: "The textures presented are rather mundane, there is no use of dynamics for effect, and the works don't show any cohesiveness to speak of. However, if he's this good now, with diligent experimentation he ought to be up there with the best in short order."[80]

Writing in Fusion magazine, Loyd Grossman pondered whether the album would have been released if not for the Beatles owning Zapple. He said that the record's shape and resistance to water made it useful as a "porthole cover" and concluded, in imitation of the noises heard on the LP: "If YOU fweemfweemfweemfweem apapapapapapap have an olD SunbeamToaster ugwachattttattachurgchurg churg and enjoyputting your dddddldddlddlllder ear up to it wwhoooooooggggg*-*- you may enjoy this album phwerpphwerp phwerp …"[81]

Retrospective assessment

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [3] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [82] |

| Mojo | [83] |

| MusicHound | 1/5[84] |

| OndaRock | 5.5/10[85] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [86] |

| Uncut | [87] |

In the 2004 Rolling Stone Album Guide, Mac Randall called the album and its predecessor, Wonderwall Music, "interesting, though only for established fans".[88] Richard Ginell of AllMusic says that the same two albums showed that Harrison defied "pigeonholing" in his projects outside the Beatles,[89] and he writes of Electronic Sound: "Though scoffed at when they were released, these pieces can hold their own and then some with many of those of other, more seriously regarded electronic composers. And when you consider that synthesizers were only capable of playing one note at a time and sounds could not be stored or recalled with the push of a button, the achievement becomes even more remarkable."[3]

In his appraisal of Harrison's solo career for Mojo in 2011, John Harris described the album as the "Fabdom" equivalent of Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music, adding: "Not exactly music, though you could conceivably assume the endless whooshes and random notes were the work of admirably out-there Krautrockers."[83] In his article on the Moog for the same magazine, in 1997, John McCready wrote that the album conveyed "caveman confusion" on Harrison's part, but he grouped it with experimental releases by Jean-Jacques Perrey, Dick Hyman, the Hellers, Mort Garson and TONTO's Expanding Head Band, saying: "It says something about the compelling-even-when-crap nature of the Moog that it is possible to own and enjoy all these records."[90]

Luke Turner of The Quietus includes it among his favourite electronic-music albums. He says that Harrison's fascination with the Moog typified the interest the new instrument received from top rock musicians at the time, and he adds: "Luckily for us he decided to release it (with a great cover painting by a small child) … While my Synth gently beeps."[91] Writing for The New York Observer, Ron Hart considers it to be one of Harrison's unjustly overlooked works and he says that while it was tainted by the controversy with Krause, the project stands as an "oddly visionary testament to the Zapple label and its unsung promise to bring the avant-garde to the pop crowd".[92][nb 6]

In a 2014 review for Uncut, Richard Williams said that just as the Beatles' fan-club Christmas records were inspired by the Goons, Harrison's inspiration for Electronic Sound appears to have been "another BBC institution of their formative years: the Radiophonic Workshop". According to Williams, the album conveys "the joy of a boy with a new toy" and "sounds like what you might get if you taped a contact microphone to the stomach of a digestively challenged robot".[94][nb 7] Scott Elingburg of PopMatters welcomed its Apple Years reissue and described the album as the artist's "most 'experimental' work" and, like the remastered Wonderwall Music, "raw and gorgeous, alive and capable of sparking ingenuity". He said that while Harrison was not a synthesizer innovator in the mould of Brian Eno or Jeff Lynne, "the intention behind Electronic Sound is one of exploration and discovery, an artist limbering up his musical mind to discover how far the boundaries of modern instrumentation could take him. Out of context, Electronic Sound would sound maudlin, even dull. Here, as a key step in the progression of Harrison the solo artist, it sounds audacious in its primitiveness ..."[95]

Influence and legacy

editElectronic Sound was one of the first electronic music albums made by a rock musician.[96] Oregano Rathbone of Record Collector called it "intriguingly indulgent, avant-Moog" and said that, as with Wonderwall Music, "The example set by the [Beatles] – that there's room for everything under the pop umbrella – legitimised and enabled an infinite variety of music from everyone's subsequent favourite bands."[97] In his book Electronic and Experimental Music, Thom Holmes discusses Electronic Sound in terms of its influence on the Beatles' Abbey Road and, with that album, their standing as "one of the first groups to effectively integrate the sounds of the Moog into their music".[14] Once installed at EMI Studios in August 1969, where Mike Vickers of the band Manfred Mann assisted in programming the system,[98] Harrison's Moog proved to be an important addition to the Beatles' final recording project.[99][100] With Harrison, Lennon and Paul McCartney each playing the instrument, the band incorporated white noise and other Moog sound effects,[101] together with melodic elements played via the ribbon controller.[102][nb 8] In January 1970, Robert Moog announced the launch of his company's Mini-Moog,[104] a synthesizer that simplified the 3P system for easy operation as a performance instrument.[105][nb 9]

Electronic Sound has never achieved mainstream popularity, even for a Beatle-solo record … While rough and unconstructed, it is a very distinctly "Moog" album, with very few other audible sound sources, and a wide variety of Moog modular sonics being demonstrated. Although the wild experimental phase of the Beatles only lasted a short time, it was a bold direction for anyone in the top of the charts to attempt, even as a side-project.[106]

– Moog Music, 2014

In their book on the history and legacy of the Moog synthesizer, Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco cite Harrison's use of Krause's studio demonstration as an example of the difficulties faced by "Moogists" such as Beaver and Krause in gaining acceptance for their efforts. The authors write that the perception in the recording industry during the late 1960s was typically that, because of the highly technical aspect of the Moog modular system, these pioneers were simply engineers rather than artists or musicians. Pinch and Trocco highlight Mort Garson's The Wozard of Iz and Mason Williams' The Mason Williams Ear Show as further examples; in the case of the latter album, Beaver was credited as being "in charge of plugging and unplugging".[107]

Hartford Courant music critic Roger Catlin has said that the album's appeal is limited to aficionados of "early synthesizer experiments".[108] Malcolm Cecil, who went on to become a leading synthesizer proponent as the co-creator of TONTO,[109][110] recalls that when he first encountered a Moog 3P, his immediate thought was: "Geez, this is the [instrument] that George Harrison made that record on. I'm looking at it, and I saw it has filters, envelope generator – what the hell is all this stuff?"[111] Tom Rowlands of the Chemical Brothers has cited Electronic Sound as an influence.[112] In his introduction to the 2014 CD booklet, he recalls discovering a rare copy of the LP in a Tokyo record shop in the 1990s and says that the sleeve "now hangs on the wall of my studio, just next to my own Moog modular, beaming inspiration straight to my brain".[113]

In 2003, Electronic Sound was featured in the "Unsung" album series at musician and musicologist Julian Cope's website Head Heritage,[114] later compiled in Cope's book Copendium: An Expedition into the Rock 'n' Roll Underworld.[115][116] The author said he relished the record for providing "all the scant moments of raging Moog-osity I always craved more of as a teenage Emerson, Lake & Palmer fanatic", and described its two tracks as "aural rollercoaster rides, featuring alarming and unusual zapping twists over an assortment of tone colours, pitch-controlled hi-jinks and outright experimentalism in the most extreme album Harrison would ever produce".[114]

Track listing

editAll pieces credited to George Harrison. US and Canadian LP pressings incorrectly switched the order of the recordings but did not switch the titles.

Side one

- "Under the Mersey Wall" – 18:41

Side two

- "No Time or Space" – 25:10

Notes

edit- ^ Among its initial appearances in the context of popular music, the instrument had been used by Beaver in 1967 on The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds[15] and on the Byrds' "Goin' Back".[16] The following year, Wendy Carlos achieved unexpected commercial success with Switched-On Bach,[17][18] an experimental work that first heralded the melodic possibilities offered by the Moog synthesizer.[19][20]

- ^ Music critic Richie Unterberger comments that although Lennon was the Beatle best known for embracing avant-garde music, and Paul McCartney subsequently went to considerable length to emphasise his own forays in the style, Harrison's absorption in Indian classical music and the sitar "were themselves avant-garde in the context of the 1960s".[25]

- ^ By comparison, when Mick Jagger received his Moog in September 1968, the company sent an employee to London to spend a week teaching him how to use the instrument.[42] In California, Krause and Beaver regularly hosted Moog classes for groups of up to 30 and individual tuition sessions for their customers.[43]

- ^ In early 1969, Harrison and Taylor were said to be writing a musical based on the chaotic goings-on at Apple.[50] While this idea was abandoned,[51] Harrison readily supported the Rutles' lampooning of the company in their 1978 Beatles satire, All You Need Is Cash.[52][53]

- ^ When announcing Zapple and its inaugural releases, Derek Taylor had written that the label's products would be priced according to three categories relating to content and production costs. The categories (with prices in the British pre-decimal system) and their corresponding catalogue designation were: 15 shillings (ZAP); 21 shillings (ZAPREC); 37 shillings 5 pence (ZAPPLE).[65]

- ^ In his liner-note essay for the 2014 reissue of Electronic Sound, Kevin Howlett reproduces Krause's claim regarding the origins of "No Time or Space" and comments: "There is no historical evidence that gives George's view of that assertion."[93]

- ^ He concluded by saying that the self-deprecating sleeve note from Arthur Wax "still sums it up".[94]

- ^ Harrison later used portions of white noise from "No Time or Space" in "I Remember Jeep", a track included on the Apple Jam disc of his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass.[103]

- ^ Moog told Billboard that Mick Jagger and George Martin also owned Moog 3Ps and that the BBC's Radiophonic Workshop was due to purchase one, but that the cost was prohibitive for musicians such as Vickers, who instead had to rent his system.[104]

References

edit- ^ Inglis 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Badgley, Aaron (24 February 2017). "Spill Album Review: George Harrison – The Vinyl Collection". The Spill Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Ginell, Richard S. "George Harrison Electronic Sound". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Leng 2006, pp. 30, 32, 50.

- ^ Simons, David (February 2003). "The Unsung Beatle: George Harrison's behind-the-scenes contributions to the world's greatest band". Acoustic Guitar. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles Yellow Submarine". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 151–52.

- ^ Clayson 2003, pp. 234–35.

- ^ Hurwitz, Matt. "Wonderwall Music". georgeharrison.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 172.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 242.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 222.

- ^ Brend 2012, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d Holmes 2012, p. 446.

- ^ Holmes 2012, pp. 246–47.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 164, 178.

- ^ Holmes 2012, pp. 249–50.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (23 September 2004). "Moog Documentary Clearly a Labor of Love". MTV.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, pp. 132, 147.

- ^ a b Greene 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Miles 2016, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 208, 242, 245.

- ^ Clayson 2003, pp. 246, 249.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 161.

- ^ White 1987, pp. 56–57.

- ^ White 1987, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d "Electronic Sound (2014 Remastered)". georgeharrison.com. September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 123–24.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 222–23.

- ^ a b c d Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 423.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, pp. 124–25.

- ^ a b Harry 2003, p. 164.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, pp. 422, 423.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 353.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Spizer 2005, pp. 209–10.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 303.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 122.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Brend 2012, p. 187.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Harry 2003, p. 165.

- ^ Miles 2016, pp. 61, 82.

- ^ a b c Spizer 2005, p. 210.

- ^ Miles 2016, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Harrison, Dhani (2014). Electronic Sound (CD booklet, "Electronic Sound by Dhani Harrison"). George Harrison. Apple Records. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Boyd 2007, pp. 7 (pic. section), 294.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 328.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 424.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, p. 366.

- ^ Clayson 2003, p. 370.

- ^ a b Miles 2016, pp. 162–63.

- ^ Harry 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Black, Johnny (2003). "A Slice of History". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. pp. 92, 92.

- ^ a b Miles 2016, p. 163.

- ^ a b Brend 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 76.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 343, 344.

- ^ Spizer 2005, p. 209.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 197, 199.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 287–88.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 118.

- ^ Miles 2016, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 118–19.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 360.

- ^ Miles 2016, p. 9.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 68, 197.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 119.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 265.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 223, 265.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, pp. 423, 634.

- ^ Clayson 2003, p. 245.

- ^ Huntley 2006, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Marchese, Joe (23 September 2014). "Review: The George Harrison Remasters – 'The Apple Years 1968–1975'". The Second Disc. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Reid, Graham (24 October 2014). "George Harrison Revisited, Part One (2014): The dark horse bolting out of the gate". Elsewhere. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Evans, Allen (17 May 1969). "George Harrison Seeks New Sounds from the World of Electronics". NME. p. 10.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 197–98, 204.

- ^ Ward, Edmund O. (9 August 1969). "John Lennon & Yoko Ono Life with the Lions / George Harrison Electronic Sound". Rolling Stone. p. 37.

- ^ Grossman, Loyd (8 August 1969). "George Harrison: Electronic Sound (Zapple)". Fusion. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Larkin 2011, p. 2650.

- ^ a b Harris, John (November 2011). "Beware of Darkness". Mojo. p. 82.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, p. 529.

- ^ Gambardella, Gabriele. "George Harrison: Il Mantra del Rock". OndaRock (in Italian). Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "George Harrison: Album Guide", rollingstone.com (archived version retrieved 5 August 2014).

- ^ Nigel Williamson, "All Things Must Pass: George Harrison's post-Beatles solo albums", Uncut, February 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 367.

- ^ Ginell, Richard S. "George Harrison Wonderwall Music". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ McCready, John (June 1997). "In a Moog Mood". Mojo. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Turner, Luke (15 February 2017). "While His Synth Gently Beeps: Benge's Favourite Electronic LPs". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Hart, Ron (24 February 2017). "George Harrison's 5 Most Underrated Albums". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Howlett, Kevin (2014). Electronic Sound (CD booklet liner notes). George Harrison. Apple Records. pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Williams, Richard (November 2014). "George Harrison The Apple Years 1968–75". Uncut. p. 93.

- ^ Elingburg, Scott (20 January 2015). "George Harrison The Apple Years: 1968–1975". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone 2002, p. 187.

- ^ Rathbone, Oregano (December 2014). "George Harrison – The Apple Years 1968–75". Record Collector. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Holmes 2012, pp. 442, 446.

- ^ Shea & Rodriguez 2007, p. 179.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 204–05.

- ^ Holmes 2012, pp. 446–47.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, p. 12.

- ^ a b Dove, Ian (24 January 1970). "Mini-Moog to Be Unveiled". Billboard. pp. 1, 98.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, pp. 85–86.

- ^ "George Harrison's 'Electronic Sound'". moogmusic.com. 10 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, pp. xvi, 529.

- ^ McDonald, Steven. "T.O.N.T.O.'s Expanding Head Band". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, p. 308.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, pp. 174–75.

- ^ Howlett, Kevin (2014). The Apple Years 1968–75 (box-set book, "The Apple Years"). George Harrison. Apple Records. p. 32.

- ^ Rowlands, Tom (2014). Electronic Sound (CD booklet, "An Introduction"). George Harrison. Apple Records. p. 3.

- ^ a b The Seth Man (January 2003). "Unsung: George Harrison – Electronic Sound". Head Heritage. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Roddy (24 November 2012). "The Art of Noise". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Litt, Toby (8 November 2012). "Julian Cope and the Psychic Underworld". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Sources

edit- Boyd, Pattie; with Junor, Penny (2007). Wonderful Today: The Autobiography. London: Headline Review. ISBN 978-0-7553-1646-5.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th edn). New York, NY: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Brend, Mark (2012). The Sound of Tomorrow: How Electronic Music Was Smuggled into the Mainstream. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-2452-5.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). George Harrison. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-489-3.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone (2002). Harrison. New York, NY: Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-3581-5.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Danie, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- Greene, Doyle (2016). Rock, Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, 1966–1970: How the Beatles, Frank Zappa and the Velvet Underground Defined an Era. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6214-5.

- Harry, Bill (2003). The George Harrison Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Holmes, Thom (2012). Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture (4th edn). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-89636-8.

- Huntley, Elliot J. (2006). Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles. Toronto, ON: Guernica Editions. ISBN 1-55071-197-0.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). The Words and Music of George Harrison. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th edn). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Miles, Barry (2016). Zapple Diaries: The Rise and Fall of the Last Beatles Label. New York, NY: Abrams Image. ISBN 978-1-4197-2221-9.

- Pinch, Trevor; Trocco, Frank (2002). Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01617-3.

- Prendergast, Mark (2003). The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby – The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. New York, NY: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-58234-323-3.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Shea, Stuart; Rodriguez, Robert (2007). Fab Four FAQ: Everything Left to Know About the Beatles ... and More!. New York, NY: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-2138-2.

- Spizer, Bruce (2005). The Beatles Solo on Apple Records. New Orleans, LA: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-5-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- White, Timothy (November 1987). "George Harrison – Reconsidered". Musician. pp. 50–67.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

External links

edit- Electronic Sound at Discogs (list of releases)