Odoacer's deposition of Romulus Augustus, occurring in 476 AD, was a coup that marked the end of the reign of the Western Roman Emperor last approved by the Western Roman Senate and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy, although Julius Nepos exercised control over Dalmatia until 480.

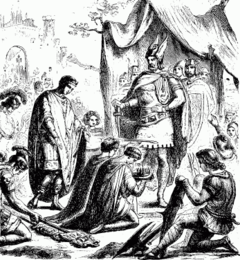

Romulus Augustus, the last Western Roman Emperor, surrenders the crown to Odoacer (1880 illustration). | |

| Date | 4 September 476 AD |

|---|---|

| Location | Ravenna, Italy |

| Participants | Odoacer Flavius Orestes Romulus Augustus Zeno Julius Nepos |

| Outcome | The overthrow of Romulus Augustus, considered to have been the final Western Roman Emperor. |

Background

editSackings of Rome

editRome had been sacked twice in the 5th century AD, after a lengthy decline which followed more than the better part of a millennium of dominance, first over central Italy and then over an empire that surrounded the Mediterranean Sea.[1][2] First, in 410 a Visigothic army under the command of Alaric besieged, entered, and looted the city, and in 455 the Vandals attacked Rome after their king, Genseric, believing himself to have been snubbed by an usurper emperor, voided a peace treaty. Despite remaining the seat of the Roman Senate, and an important city of the Western Roman Empire, Rome was not what it had once been – the Western emperors had moved their courts to the more secure Ravenna in the wake of the two pillages and the Hun incursions.

The Vandals were allowed to enter the city after promising the Pope to spare its citizens, but they carried off many of the unfortunate Romans, some of whom were sold into slavery[3] in their captors' North African realm. The widow of the emperors Valentinian III and Petronius Maximus, Licinia, was herself taken to Carthage, where her daughter was married to Genseric's son.

Rome not only lost a portion of its population during the Vandal rampage, but a fairly large amount of its treasures was plundered by the barbarians. This loot was later recovered by the Byzantines.[4] At the time, however, its loss was a major blow to the Western Empire.

Ricimer and other generals dominate

editAfter Rome's weaknesses were exposed by the Vandals' invasion, the barbarian tribes of Gaul, once a secure province loyal to the Empire, began to rebel against their former overlords.[5] The Ravenna-based emperors now began to lose the respect of many of their subjects, and powerful generals, often of barbarian origin themselves, were forced to defend them. Among the more successful of these commanders, the most senior of whom were called magistri militum, were Avitus, who would eventually be crowned emperor, and Ricimer (who was part-Sueve and half-Visigoth). Ricimer grew so powerful that he was able to choose and depose weak emperors almost at will.[6]

In 475, the Western emperor, Julius Nepos (nephew of the Eastern empress), was overthrown by his magister militum, the aristocratic Orestes, who had once been a trusted official of Attila, the Hun ruler.[7] Rather than take the throne himself, Orestes had his young son, Romulus Augustulus, crowned emperor.

Odoacer's coup and accession

editOrestes, who ruled in his son's name, found an enemy in the persons of his non-Roman mercenary soldiers. When, led by an auxiliary general called Odoacer, they demanded estates and were refused,[8] they swept into Italy. Informing his soldiers that, if they followed and obeyed him, they would, in the words of Gibbon, "extort the justice that had been denied to their dutiful petitions", the Germanic, Arian Odoacer confirmed his leadership of the revolt. Barbarian soldiers in Italian cities and garrisons "flocked" to the audacious general's standard, and Orestes fled to fortified Pavia. Odoacer laid siege to Pavia, which fell in due course. The bishop of that city, Epiphanius, managed to ransom many of the captives taken during this invasion,[9] but was unable to save Orestes, who was executed.

Orestes' brother was killed near Ravenna by Odoacer's forces, who entered the imperial capital soon afterward. The young monarch Romulus Augustulus was, on 4 September, compelled to abdicate before the Senate. That body requested that the Eastern Roman Emperor, Zeno, reunite his realm with the West, with Odoacer as his governor. The auxiliary commander, now master of Ravenna, encouraged the senators in this effort.[10][11] The emperor was somewhat hesitant to give Odoacer what would be relative autonomy, citing that his wife's nephew Julius Nepos, still alive and recognized as caesar in Dalmatia, should be restored to the throne. Zeno, however, did not want to use force to support his relation, so, while still urging Odoacer to recognize Nepos' claim, granted the general the rank of patrician[12] and accepted the general's gift of the Western imperial standards.

The hapless ex-emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was still present in Ravenna, and Odoacer rid himself of the boy by exiling him. The fate of this final Western Roman emperor is somewhat uncertain, but it is believed that he retired to the Lucullan Villa in Campania[13] and died before 488, when the body of the saint Severinus was brought there. In 480, the second of Odoacer's Roman rivals, Julius Nepos, was assassinated by "retainers".[14] Until Nepos' murder, even the confirmation of Odoacer's patrician rank and authority had been undermined by the presence of Zeno's nephew.[15]

Odoacer now proclaimed himself king of the Herules in Italy (476–493), but not king of Italy, as Italy formally remained a land of the Roman Empire after absorbing Augustus's powers, and formed alliances with other barbarians, a prime example being the Visigoths. He proved himself to be a capable ruler, and, although Italy was beset by disasters such as plagues and famines during the turbulent end of the 5th century, historians such as Edward Gibbon have attested to Odoacer's "prudence and humanity".[16]

Aftermath

editDespite possessing these qualities, Odoacer was unable to defeat the Ostrogoths and their monarch, Theodoric the Great, who invaded the Kingdom of Italy and overcame the forces that defended it. After four years of fighting, Odoacer, with some pressure from his citizens and his soldiers, decided in 493 that it would be useless to continue fighting and surrendered. The conqueror of the Western Roman Empire was himself conquered, and, unlike Romulus Augustus, he was not spared. While enjoying a banquet, he was murdered by an Ostrogoth, who may have been Theodoric himself.[17]

When the Ostrogothic queen Amalasuntha, a Byzantine ally, was executed by her chosen successor Theodahad in 535, the Eastern Emperor, Justinian, did not hesitate to declare war. Under the command of the general Belisarius, an army landed in Sicily and subdued that island before invading Italy proper.[18] When he did invade the peninsula, he took the city of Naples, then attacked and captured Rome. For nearly twenty years,[19] the Ostrogoths and Romans fought for control of the peninsula. The suspicions of the Eastern empress, Theodora, often led her husband Justinian to withhold reinforcements from Belisarius, who was recalled several times. Some historians[20] have concluded that the war's successful conclusion was the victory of Belisarius, but the honor of defeating the Ostrogoths went to Narses, who was trusted far more by his superiors in Constantinople. Eventually, after the Roman reconquest, another barbarian tribe, the Lombards, invaded and settled in Italy.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Robinson, Cyril E. A History of Rome from 753 B.C. to A.D. 410. Methuen, 1963.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3, p. 623. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Brownworth, Lars. Lost to the West. 2010, Crown Publishing Group.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3, p. 624. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3, p. 636. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3, p. 638. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Hill, David Jayne. A History of Diplomacy in the International Development of Europe, Vol. 1, p. 32. Longmans, Green, and Co, 1905.

- ^ Bryce, Viscount James. The Holy Roman Empire, p. 27.

- ^ Bury, J.B. History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I, Vol. 1, p. 407. Dover Publications, 1958.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3, p. 640. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Bury, J.B. History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I, Vol. 1, p. 410. Dover Publications, 1958

- ^ Bury, J.B. History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I, Vol. 1, p. 410. Dover Publications, 1958

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol 3, p. 641. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 4, p. 692. Ed. Hans-Friedrich Mueller. Modern Library, 2003

- ^ Young, George Frederick. East and West Through Fifteen Centuries, Vol. 2, p. 220. Longmans, Green and Co, 1916

- ^ Young, George Frederick. East and West Through Fifteen Centuries, Vol. 2, p. 220. Longmans, Green and Co, 1916

- ^ Brownworth, Lars. Lost to the West. 2010.