Deus revelatus (Latin: "revealed God") refers to the Christian theological concept coined by Martin Luther which affirms that the ultimate self-revelation of God relies on his hiddenness. It is the particular focus of Luther’s work the Heidelberg Theses of 1518,[1] presented during the Heidelberg disputation of 1518. In Christian theology, God is presented as revealed or Deus revelatus through the suffering of Jesus Christ on the cross. Debate of the term is found in the field of philosophy of religion, where it is contested among philosophers such as J. L. Schellenberg.[2] The term is usually distinguished from Luther's concept of Deus absconditus, which affirms the fundamental unknowability of the essence of God. However, Luther proposed that God is a revelation who uses the fog to obscure himself.[3] This distinction which permeates his theology has been the subject of wide interpretation, leading to controversy between theologians who believe the terms to be either antithetical or identical. These two conflicting strands of thought present the main problem when interpreting Luther’s doctrine of the Revealed God.[4] In recent years the term has been used to inform modern analysis of religious themes such as evolution.

The Revealed God

editChristian Theology

editThe conception of Luther's Revealed God came about through his own personal struggles with grasping assurance of God's grace, which he confirmed by looking to the Cross of Christ. The concept of the incomprehensibility of God was first introduced by Luther in his Lectures on The Psalms.[4] The theology of ‘deus revelatus’ originated to address the concern that if a God exists, he has not made his existence sufficiently clear.[5] The term ‘Revealed God’ can be found in Luther’s works, Heidelberg Theses (1518) and On the Bondage of the Will (1525). Luther’s theology was permeated by the theology of the cross, which led to the conception of both the Revealed God (deus revelatus) and the hidden God (deus absconditus). In the Heidelberg Thesis, Luther asserts the view of ‘deus revelatus', a living God who suffered on a cross, and in On the Bondage of the Will Luther depicts the ‘deus absconditus’, a God of hidden majesty. The Christian concept of God depicts an absolute being who is righteous in himself, thereby becoming a threat to unrighteous humans. Therefore, He must become 'the God who seeks to be justified by the unrighteous in his words, a great vulnerability in which God stoops low in order to give sinners faith'.[3]

The concept of the Revealed God was later referred to by Paulson as 'The Preached God'.[3] The Revealed God is one being and three persons who 'actively wants to be found—in Christ, and him crucified—justified in his words'.[3] Luther thus proposed that God’s ultimate self revelation is in hiddenness, ‘namely, in weakness, in folly, in the incarnation and on the cross’.[1] The divine majesty and glory of God is ‘shame and humiliation’ as he ‘brings life by means of death, whose suffering leads to resurrection’, thus there becomes a paradox whereby God is hidden in His self-revelation.[1] God is hidden ‘in the suffering, humility and shame of the cross’ and ones suffering on Earth, however through faith sinners can recognise the God of love and mercy revealed in Christ.[6] Such a revelation which leads to justification nevertheless requires a preacher, thus 'The Holy Spirit sends such preachers so that grace is not so deeply hidden that we never find Christ hidden in the repulsive cross'.[3] Because of this, Luther’s theology states that any individual outside of a Christian community of faith do not experience his self-revelation and do not know his attitude towards them.[1]

Luther believed that the visible aspects of God through his hiding were the only sufficient explanation of God. Therefore, Luther stated it was imperative that theologians focus on the cross to ‘see God as God wants to be seen’.[1] ‘Those who seek to know the invisible things of God, namely, God's glory, majesty, wisdom, and justice, through the wisdom of natural revelation are chastised as theologians of glory by Luther’.[1]

The concept connects to free will within Christian theology as it leads to the belief that ‘God must remain hidden […] failing to do so would lead to a loss of morally significant freedom on the part of creatures’.[5]

In the Bible

editLuther’s conception of the Revealed God was derived from specific scripture in the Christian bible which detail how only through Christ does God choose to be revealed. Passages of significance include John 14:8-9, ‘8 Philip said, “Lord, show us the Father and that will be enough for us.” 9 Jesus answered: “Don’t you know me, Philip, even after I have been among you such a long time? Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’?’.

Further passages of importance

editSource:[1]

- Exod 33:18-23

- Rom 1:19-25

- 1 Cor 1:17-31

- 2 Thessalonians 2:4

Philosophy of religion

editThe Revealed God contributes to debate in Philosophy of Religion whereby philosophers such as J. L. Schellenberg have used it to support the view of atheism.[5]

Schellenberg’s line of argument attempts to disprove the Judeo-Christian-Islamic God by stating that were there a perfectly loving God, He would adequately reveal Himself to allow every person to attain personal relationship with Him. However, since ‘there are capable, inculpable non-believers […] there is no perfectly loving God’.[5]

Schellenberg’s Argument:

- If there is a God, he is perfectly loving

- If a perfectly loving God exists, reasonable nonbelief does not occur

- Reasonable nonbelief does occur

- No perfectly loving God exists

- There is no God

Similar: 'The Hidden God'

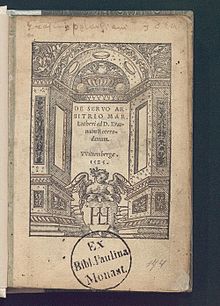

editA similar Lutheran concept is that of the Hidden God, a deity whose grace is hidden, which is often considered to be interconnected to the Revealed God. Luther’s depiction of ‘deus absconditus’ can be found in his work Bondage of the Will (De servo arbitrio). Luther’s concept asserts that the first instance of hiding in the Christian Bible occurred in the garden of Eden where Adam and Eve sought to hide from God.[7] Following this instance, God has remained hidden in the sense that his will and counsels remain unknown to any except him.

There are two contrasting views of the implications of Luther's depiction of a Hidden God:[3]

- His hiddenness is the subjective limit of human knowledge.

- God is in essence mercy, so acts that appear evil can be attributed to the attribute of divine love.

Controversy

editA prevalent issue in theological scholarship is the relationship between the Revealed God and the Hidden God. Controversy has arisen as to whether the ‘deus revelatus’ and ‘deus absconditus’ refer to two distinct strands of theology which only have the concept of hiddenness in common, or are identical in form. It is claimed that according to his own writings, 'Luther never preached two or three gods or powers; he was not a Manichaean or anti-Trinitarian',[3] however a seeming paradox is contested. Gerrish forms two differing groups of theologians dependent on whether they believe the terms are antithetical or identical.

Theologians who believe the terms are antithetical include Hendel, Theodosius Harnack, the two Ritschls, Reinhold Seeberg, Hirsch, Elert, and Holl. Such theologians argue the dualistic nature of the terms and state that the two differing views of God they produce cannot be reconciled. Hendel states ‘Luther warns that the theologian and believer must distinguish between the God preached, or revealed, and the God hidden, "that is, between the Word of God and God himself”’.[1] Harnack’s work was considered to be a rediscovering of the concept of the Hidden and Revealed God whereby ‘the notion of hiddenness expresses a double relation of God to the world: outside of Christ he is the free, all-working, majestic God of the Law; in Christ he is the gracious Redeemer who has bound himself to his Word and Sacraments’.[4] This position was also held by Althaus who stated that through his conception of the Revealed and Hidden God, Luther divided God; 'God, according to His secret will, to a great extent disagrees with His Word offering grace to all men'.[8]

Theologians who believe the terms are identical are Kattenbusch and Erich Seeberg. The theologians argue that a single event of revelation led people through faith to see the Revealed God, and through simply sense-perception see the Hidden God. Kattenbusch perpetuated the standpoint of the two terms as identical, asserting that ‘God hides himself in his revelation, so that revelation and hiddenness are not opposed, but coincide’.[4]

Modern Theological Application

editLuther’s theology has remained relevant in a multitude of modern theological debates such as evolutionary debate.

Evolutionary Debate

editTheologian Charlene Burns has examined meaning of violent evolution with regards to Christian theology. Scientific discoveries continue to uncover violence as a marker of the origin of the world, from the ‘movement of fault lines in the earth to the extinction of species’.[9] Burns uses a phenomenological approach to discuss the violence which is inherent to evolution.[9] Burns states that ‘God is revealed not in the suffering of Christ on the cross, per se, but in what that suffering stimulates’, and states that evolution has led to humanity becoming ‘destroyers’.[9] Burns concludes by asserting that the idea of God being revealed through the suffering of Christ exemplifies the altruistic nature of God, which humanity is called to emulate in its current advanced stage of evolution.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Hendel, Kurt K. (August 2008). "'No salvation outside the church' in light of Luther's dialectic of the hidden and revealed God". Currents in Theology and Mission. 35 (4): 248–258. Gale A182929962.

- ^ Schellenberg, J. L. (1993). Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2792-3.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g Paulson, Steven (2014). "Luther's Doctrine of God". In Kolb, Robert; Dingel, Irene; Batka, L'ubomír (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther's Theology. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604708.013.034. ISBN 978-0-19-960470-8.

- ^ a b c d Gerrish, B. A. (1973). "'To the Unknown God': Luther and Calvin on the Hiddenness of God". The Journal of Religion. 53 (3): 263–292. doi:10.1086/486347. JSTOR 1202133. S2CID 170113518.

- ^ a b c d Howard-Snyder, Daniel; Moser (2002). Divine Hiddenness: New Essays. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521006101.

- ^ Stopa, Sasja Emilie Mathiasen (1 November 2018). "'Seeking Refuge in God against God': The Hidden God in Lutheran Theology and the Postmodern Weakening of God". Open Theology. 4 (1): 658–674. doi:10.1515/opth-2018-0049. S2CID 172127916.

- ^ Paulson, Steven (1 October 1999). "Luther on the Hidden God". Word & World. 19 (4): 363–371.

- ^ Althaus, Paul (1966). The Theology of Martin Luther. Fortress Press. ISBN 0800618556.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Burns, Charlene P. E. (November 2006). "Honesty about God: Theological reflections on violence in an evolutionary universe". Theology and Science. 4 (3): 279–290. doi:10.1080/14746700600953389. S2CID 144946281.

Bibliography

edit- Burns, Charlene P. E. (November 2006). "Honesty about God: Theological reflections on violence in an evolutionary universe". Theology and Science. 4 (3): 279–290. doi:10.1080/14746700600953389. S2CID 144946281.

- Claus Schwambach: Rechtfertigungsgeschehen und Befreiungsprozess. Die Eschatologien von Martin Luther und Leonardo Boff im kritischen Gespräch, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-525-56239-X

- Gerrish, B. A. (1973). "'To the Unknown God': Luther and Calvin on the Hiddenness of God". The Journal of Religion. 53 (3): 263–292. doi:10.1086/486347. JSTOR 1202133. S2CID 170113518.

- Hans Hübner: Biblische Theologie des Neuen Testaments, Band 1: Prolegomena, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1990, ISBN 3-525-53586-4

- Hendel, Kurt K. (August 2008). "'No salvation outside the church' in light of Luther's dialectic of the hidden and revealed God". Currents in Theology and Mission. 35 (4): 248–258. Gale A182929962.

- Howard-Snyder, D. & Moser, P. K. (2002) Divine hiddenness new essays. Cambridge, UK ;: Cambridge University Press.

- Kolb, Robert (2009). Martin Luther: Confessor of the Faith. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-920894-4.

- Paulson, Steven (2014). "Luther's Doctrine of God". In Kolb, Robert; Dingel, Irene; Batka, L'ubomír (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther's Theology. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604708.013.034. ISBN 978-0-19-960470-8.

- Paulson, Steven (1 October 1999). "Luther on the Hidden God". Word & World. 19 (4): 363–371.

- Schellenberg, J. L. (1993). Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2792-3.

- Stopa, Sasja Emilie Mathiasen (1 November 2018). "'Seeking Refuge in God against God': The Hidden God in Lutheran Theology and the Postmodern Weakening of God". Open Theology. 4 (1): 658–674. doi:10.1515/opth-2018-0049. S2CID 172127916.

- Vestrucci, Andrea (2019). Theology as Freedom: On Martin Luther's "De servo arbitrio". Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-156975-3.

- Leppin, Volker (2005). "Deus absconditus und Deus revelatus. Transformationen mittelalterlicher Theologie in der Gotteslehre von 'De servo arbitrio'". Berliner Theologische Zeitschrift. 22 (1): 55–69. doi:10.15496/publikation-53935. hdl:10900/112559.