| This is a draft article. It is a work in progress open to editing by anyone. Please ensure core content policies are met before publishing it as a live Wikipedia article. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL Last edited by MinorProphet (talk | contribs) 4 months ago. (Update)

Finished drafting? or |

| Join in and help expand this draft! |

Editorials, 17 August 2020 & 1 May 2021

editBlimey, it just gets longer and longer.

- Notes to self - please ignore

The 'Nomenclature' section was originally quite short, but having read Shelagh Mitchell I see that the Latin terms I have used are of the third-person CPR style. The patent rolls IN LATIN from e.g. Edward IV onwards just don't seem to be available, either images of the originals, or in record type. But is seems that this is just what I need in order to penetrate the mystery of e.g. 'knight of the royal body' - it may just be an idiosyncrasy of the 19th century translators, or could be a different phrase in Latin.

There is now a lot of indirect material dealing with the running of the localities, shires, counties etc., and also stuff about the running of the actual royal household - but this is exactly what the knights (occasionally) may have done - i fink - and I feel that it's all still relevant. This is not comprehensively covered on WP. There are also conflicting views of various schools of historians, although in some ways these are extraneous to the bare 'facts' of who actually was termed a knight for the body (cue bitter laughter), and the jobs they did.

- NB You need to stick your mind inside the head of a king. MinorProphet (talk) 14:07, 1 May 2021 (UTC)

The section enumerating what the Knights of the Body weren't is essential, i fink: it's taken really quite some time just to identify the knights for the body from the rest of them, and no thanks to historians who wilfully interpret one phrase as meaning something else. There is a nagging desire to make a complete list of every single knight of the body ever - but that would be worryingly, mind-bogglingly, time-consuming and I have other, much more satisfying things to do... See Shaw, The Knights of England, Vol I, Intro. pp ix–x re pointless historical investigations.

At the moment there are several sections which run through the same chronology of kings. There are several reigns when there are no knights for the body, certainly in the patent rolls. The chamber accounts for the Yorkist kings Edward IV and Richard III are simply non-extant (Horrox 1988) because they were deliberately omitted at the time: this is a pity, because that's when the knights came into a sizeable existence numbered in several tens, rather than a small handful under the Lancastrians Henry V and VI.

There are scattered, almost one-off, single instances of the knights as far back as Edward III, and under Henry IV and V; and unless or until I find more evidence to the contrary, the knights' significant history appears to begin during the second reign of Edward IV after Tewkesbury, grows through the short rule of Richard III, expands considerably under Henry VII and ends with Henry VIII. This means that quite a lot of the background searching through the CPRs with 0 hits can be condensed into a single summary section stating that there seems to be little or no record of the knights during this period.

There may well be a case for gathering all the relevant material to do with the knights under each monarch into four main sections. Also attempting to put all the other sections into chronological order, although quite a lot of it is already thusly arranged.

- TTD

- Remove full dates from section titles - messy. Done

- Move dead-end searches to the end. Done i fink

- Find other stuff in local notes file and move here.

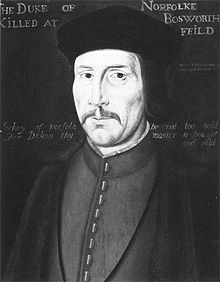

- Find some pics, it's just a wasteland of text otherwise.

- Gather all the main sections sections and the background info together. Done

More importantly, I have found a huge amount of material already which (although it has been interesting to discover) is not in fact relevant to the subject of the article. Some bits can be merged with other articles - but unless I intend to make an ill-advised attempt to list every single knight for the body, filling the article with "potted histories" or finding random factoids and refs about those who don't have a WP article is not in fact going to be much use, and time-consuming to boot. There are far too many direct lengthy quotations about e.g. 'knighthood', 'gentry', 'households', 'affinities', etc., and lots of précis needs doing, or just pointing towards the sources. (All now grouped into Background info. Done)

For some men the position seems to have been a stepping stone to greater things; others remained as esquires or knights for the body much of their careers; others rebelled and lost their liberty or lives; and others will perhaps be difficult to track down at all.

Perhaps going through the actual hits I found in the CPRs and extracting some of the more interesting people as examples - this needs doing anyway, finding specific men filling specific positions. It's just the same old search for power, or riches, or glory.

It's plainly time to

- a) Convert/move all existing

indented sourcesetc. into {cites}, make {sfn}s, and move to the Bibliography. - b) Make cites in Biblio for all bare refs for CPRs etc, and make {sfn}s. (only 150 years' worth lol)

- c) Fix all other incomplete refs, semi-bare urls etc. as {cite}s.

- d) Make it fairly plain that the first attested Knights of the Body—according to modern [ie 21st century] historians—seem to have been created by Edward IV; and that almost all other earlier references to them (and some later ones) are quite possibly i) the result of ignorance of specific Latin terms by the translators of the Calenders etc.; ii) and/or lack of access to the original contemporary documents (eg those kept in the Tower and examined by Rymer himself in person); iii) and/or the desire to portray historical figures with the most exalted possible title, even though this is generally unwarranted, as is demonstrated below.

- e) Condense various sections with overlapping material re each monarch into maybe just a single sub-section, moving all those negative "0 hits" into a single ref. NB This could well be seen as WP:OR, although multiple negative results do not confirm the opposite.

- f) Consider creating

{{uses sfn}}to explain my preferred reffing style and how to get the best out of it. - g) Find pix

- h) Is that all? (NB This is the symbol which represents the Gödel number for 0=0 [1]) MinorProphet (talk) 22:41, 15 November 2021 (UTC)

Update

editGet help. MinorProphet (talk) 12:47, 1 February 2024 (UTC)

Lede

editThe Knights for the body (or knights of the body or knights of the royal body) were prominent knights of the royal household serving the kings of England (and sometimes their queens and their heirs) from between c1400 to c1520 (from Henry IV to Henry VIII). The equivalent back-translated Latin term is miles (pl. milites) pro corpore regis. These 'royal knights' were retained by the king, with fees and robes appropriate to their status.

- NB In this draft I indiscriminately use my own abbreviations KftB ('knights for the body'), KotB ('knights of the body') or KotRB ('knights of the royal body'), or similar; plus random capitalisation of these titles.

The duties of the knights with this official or honorary title varied over the 150 years or so they were in existence, as the monarchy became increasingly adept at remaining in power. This period included the end of the Hundred Years' War, the Wars of the Roses and the War of the League of Cambrai.

During this era the knights seem to have fulfilled various functions, depending on the style of the King's rule. Firstly, they acted as the kings' literal bodyguard, surrounding him in battle and guarding his door at night in court; secondly, waiting on him at table and in his bedchamber, much like the esquires for the body; in the third place, they served as local administrators in the shires, acting as sherrifs or escheators, sitting on legal commissions of e.g. oyer and terminer or assize and thus reinforcing the concept of the monarch as the absolute arbiter of justice in the kingdom; fourthly, they were appointed to Crown offices such as keepers of royal parks and other demesnes, wardens of royal forests and castles, or as Lieutenant of Calais; fifthly, the more senior among them went on diplomatic missions to discuss and finalise treaties with foreign powers, or were appointed as one of the king's councillors; and lastly they took part in state occasions such as royal weddings, coronations, religious feast days and funerals.

All these duties had been carried out in the earlier mediaeval period by similarly rewarded 'royal knights', retained with different titles, including knights banneret, chamber knights and household knights, the so-called 'king's knights' of Richard II. The knights for the body of the later mediaeval period combined their functions as the monarch's (hopefully) trusted and loyal servants, although siding with rebellious nobles or magnates usually ended up with an execution or two.

The knights for the body were expected to be at court for some considerable time (eight continuous weeks under Edward IV)[1] and be at close quarters with the king, not unlike the esquires for the body: the latter were the most personal servants of the king, dressing him, personally him serving at table etc.

On receiving a knighthood, esquires of the body did not automatically become a knight of the body. Some esquires of the body were indeed knights; others preferred to remain un-knighted and to pay a fine to do so.§[2] Neither was there any inherent right to the position or title: it was granted by the reigning monarch (or their representative), and there was no automatic continuation of the title from one reign to another. E.g. see below Perient, Sir Henry Retford, et al.

The knights also took part in ceremonial state occasions such as royal weddings and funerals: e.g. Henry V's coronation, Edward IV's funeral (see below}, Henry VII's funeral, Edward VI's christening (Pegge, Curalalia somewhere i fink). Queens also had knights for the body, whose wives were sometimes royal ladies-in-waiting or the earlier higher-ranking 'damsels';[3] and some served various heirs to the throne, eg Henry V when Prince of Wales.

- Move to sources Dunn, Caroline (2016). "All the Queen's Ladies? Philippa of Hainault's Female Attendants". Medieval Prosopography. 31. Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University through its Medieval Institute Publications. JSTOR 44946947. NB perhaps expand this

In 1518 temp. Henry VIII, the king created a new household position called the Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, specifically for sons of noblemen. However, he chose some obnoxious and undesirable young men (the 'Minions') to join their ranks, who were swiftly were ejected from its membership and some considerable re-organisation of the Chamber took place under Thomas Wolsey. Four older and wiser knights replaced the 'Minions', who became known as the 'Knights of the Body in the Privy Chamber'.[4] The functions of the esquires of the household may have merged into the Gentleman around this time.[5] The Gentlemen seem to have provided many ambassadors from the 1520s.

It seems that none of the three subsequent monarchs Edward VI in his minority, Mary I nor Elizabeth I chose to retain knights of the body left over from previous reigns, and by around 1600 it appears that the title had fallen into abeyance. One of the last surviving knights of the body to Henry VIII was Sir James Boleyn of Blickling, Norfolk (the uncle of Anne Boleyn), dying in 1561.

The knights of the body were both intimate members of the royal household, and also maintained important positions in the shires (or in English-occupied France) away from court: they can thus also be seen as part of the king's wider affinity.[6]

Nomenclature

editSources

editMuch of the evidence about the knights is found in various official document lists such as the abbreviated Calendars of the Patent Rolls in particular, but also the Close Rolls, Pipe Rolls and Fine Rolls. The rolls were written by scribes or clerks in shorthand mediaeval Latin and French, and are today almost indecipherable except by expert specialists. Many of the Calendars have been translated into English and published, including the whole series of the Patent Rolls. Online versions are listed here: Medieval source material on the internet: Chancery rolls. The earliest rolls of the time of King John have been transcribed and printed in record type which faithfully reproduces as far as possible the complex manuscript squiggles.[7] An explanation of the shorthand is here:

- Nicolas, Nicholas Harris (1831). "Explanation of the Contractions Used in Records". Public Records: A Description of the Contents, Objects, and Uses of the Various Works Printed by Authority of the Record Commission; for the Advancement of Historical and Antiquarian Knowledge. Baldwin and Craddock. pp. 133–5.

- Hardy, Thomas Duffus, ed. (1835). Rotuli Litterarum Patentium in Turri Londinensi Asservati. Volume 1, part 1. [1201-1216]. Printed by Command of His Majesty King William IV, under the direction of the Commissioners on the Public Records of the Kingdom.

However, as Shelagh Mitchell has demonstrated, there are various shortcomings in the translations into English by the editors of the printed Calendars of the Patent Rolls. These are intended as swift summaries of the contents of the original mediaeval Latin documents, but in some instances the 19th century translators did not take into account their very particular stylistic Latin conventions. Specifically, Mitchell concentrates on the term 'king's knight', and how it fails to distinguish between royal 'chamber knights' of the household who received fees and robes from the Wardrobe, and other 'king's knights', e.g. knights who received a variety of annuities and rewards but seemed to be excluded from the household.[8]

- "...the expression miles regis (‘king’s knight’) appears only very infrequently in contemporary documentation. Rather, where the men styled ‘king’s knights’ in the printed calendars of Chancery documentation – from which Given-Wilson took his lead – appear in the original rolls, the terminology used was miles noster (‘our knight’). More specifically, Mitchell has shown how, in the original rolls, knights who were the retainers of the king were referred to as dilectus et fidelis miles noster N[ame]. Knights who were not retained by the king were, in contrast, referred to as dilectus et fidelis noster N[ame] miles. The subtle yet important difference here was that, in the former case, the individual’s rank of ‘knight’ (miles) was attached to the possessive pronoun 'our' (noster), whereas in the latter case it came at the end of the phrase simply to denote the individual’s rank.[9][10]

In fact 'king's knight' is a "blanket expression" for three different Latin and French phrases. Modern historians working from the translated and printed calendars as if they were primary source material have tended to take the translated terms at face value, which has led to confusion and contradiction.[11]

In much the same way the terms 'knight for the body' and similar expressions have also been bandied around by modern historians without necessarily checking against the original manuscript documents; or have even used the term 'knight for the body' when 'king's knight' or similar is printed in the Calendars. See § Richard II (1377–1399) below.

Terminology

editThis section is necessarily somewhat conjectural, since I have not had the opportunity of examining any Latin text e.g. a calendar dealing with the knights for the body, for example from the time of Henry VI, or Richard III etc. (apart from a small handful of entries in Rymer's Foedera).

The main Latin term used to refer to an individual knight is miles pro corpore regis, which strictly translates as 'knight for the body of the king', where pro means 'for', or 'on behalf of' and takes the ablative case of corpus, namely corpore. The plural is milites, 'knights'. Sometimes the term miles pro corpore domine regis is found, 'knight for the body of the lord king'.

These terms relating to 'knights for the king's body' appear with increasing regularity from around 1400,[12][13] and especially from 1471 after the Battle of Tewkesbury when Edward IV regained his throne from Henry VI, although there are periods when they are not mentioned at all in the Patent Rolls.

However, the Calendars turn the King's direct speech into indirect, third-party references. When the king himself is speaking to a knight in a letter patent (etc.), he addresses them as miles pro copore nostro, 'knight for our body' where nostro is the ablative singular form of noster, 'our'.

But taking Mitchell's work briefly discussed above into account (and also below), this is likely to be a back-translation into indirect speech from the original direct speech using the dative case, for example 'to N[ame], knight for our body', "N[ame] pro corpore nostris militis"[14]

Other English terms can be encountered, including 'knight of the body', and 'knight of the royal body'. I still haven't seen the Latin phrase which corresponds to either term, which may be pro corpore nostris regiis, using the adjective regius. Perhaps the king did use the form 'To N, knight for our royal body', but it seems most difficult to be able to compare the original manuscript calendar with any printed text dealing with the knights for the body, and we are left with the idiosyncrasies of the translators.

The published series of translated Calendars of the Rolls listed above use fairly consistent terms, but it is best to check them against the claims of historians, since they may have been mis-identified. The knights' titles in Latin remain a fairly exact guide to establishing their correct title in English: some of them are given below.[a] All references to 'knights of the body' before c1438 (temp. Henry VI) and 1475 (temp. Edward IV) need very careful checking, and should be treated with extreme doubt if the phrase miles (pl. milites) pro corpore regis or very similar does not appear. In particular, Shelagh Mitchell's work tends to indicate that 'king's knight' ≠ 'knight for the body'.

- Other kinds of knights

- banneretti hospicii regis - military household knights banneret

- milites familiae regis - knights of the household (since at least John c1200 and Edward I c1270)

- milites regis - king's knights (temp. Richard II)

- milites de camere regis - chamber knights (since mid reign of Edward III c1345/60?)

- miles simplex - a plain knight [b]

- equites pro corpore regis - "knights of the king's bodyguard" (temp. Henry V).[15] Hmm. Although the Latin term is here rendered as 'knight of the king's bodyguard', how does eques (pl. equites) differ from miles? Du Cange, Eques2 defines eques as "Titulus honorarius militi inferior", an inferior type of miles. And is 'knight for the king's bodyguard' just another (perhaps earlier) expression for 'knight for the king's body'? More hmmm.

- milites comitatus - knights of the shire (from 1265, two MPs were returned to represent county constituencies)

- Esquires, etc.

- scutiferi pro corpore regis - squires of the body (since at least Edward I and probably much earlier)

- armigeri pro corpore regis - king's squires (?)[c]

- sagittarii pro corpore regis - archers of the body - with the archers of the guard they made up the king's bodyguard. Later became Yeomen of the Guard.

See also Du Cange et al., Glossarium mediæ et infimæ latinitatis. Niort : L. Favre, 1883-1887 - Excellent Latin glossary, with some examples from this period.

- What they weren't...

- Knights Banneret[d]

- Household knights (but see the Liber Niger of Edward IV, where they are thus described)

- King's knights

- 'Chivaler', a late mediaeval term meaning 'knight', equal to Fr. 'chevalier'

- Knights bachelor [NB They may well have been knights bacheler, but this does not equate to being a knight for the body.]

- Chamber knights

- Knights of the Carpet[16] e.g. created the day before Edward IV's coronation

- Knights retained by a royal fee, possibly for life, but with no other title (see Hefferan p. 81)

- Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber (except Knights for the Body in the Privy Chamber)

- Knights of the Shire - these were not classed as royal knights. They were supposed to be knighted MPs, but often weren't.[e] At least one Knight of the Body (Sir John Huddleston) was also a Knight for the Shire under Henry VII - see #Henry VII (1485–1509)

- Esquires or squires of any sort, although esquires of the body could be knights, and under Henry VIII at least one man became a knight of the body before he was knighted.

- Wood-Legh, K. L. (July 1931). "Sheriffs, Lawyers, and Belted Knights in the Parliaments of Edward III". The English Historical Review. 46 (183). Oxford University Press: 372–388. JSTOR 552672.

But: "In 1366, a list of 34 persons for whom robes were provided for the Christmas festivities included 23 bachelerii, who appear to have been the ‘chamber knights’. All 13 of those who had served as chamber knights in 1364 featured amongst the 23 men listed as bachelerii, and of the other 10, four can be found serving in the household in either the late 1350s or the 1370s. This correlates well with what J. M. W. Bean found in his research into the registers of the households of John of Gaunt and the Black Prince, where bachelerii was used to denote a core group of knights who were elsewhere described as ‘knights of the chamber’.( 25 J. M. W. Bean, "Bachelor and Retainer", Medievalia et Humanistica, new ser., iii (1972), pp. 117–31.) Allowing for such early variations in language, the 1360s nevertheless stand out as the most important decade in the transformation of ‘household knights’ into ‘chamber knights’."[9]

Peter Coss recaps on Bean's article: the bachelor was "a special kind of retainer associated, whatever the precise provenance of the payments made to him, with service in the household, and enjoying a more intimate relationship with his lord than did other knightly retainers who did not have his status". The term derives from young, landless or near landless, and generally unmarried, warriors who were given bed and board in households in return for military service. "The term, Bean argues, was kept even when the bachelors were given land, as long as they still attended the lords in their households."[18] Evidence is coming to light that such men were already in receipt of fees from landed estates in the 13th century.[19]

- Coss, P. R. (November 1989). "Bastard Feudalism Revised". Past & Present (125). Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society: 27–64. doi:10.1093/past/125.1.27. JSTOR 650860.

The antiquary Simon Pegge, in his Curalalia, published in 1782, [20] seems to have been confused about the relationship between esquires and knights for the body:

- "The Esquires of the Body then, Sir, were in the department of the Lord Chamberlain, their duty being, for the most patrt, in the rooms above stairs : they were Gentlemen of birth, or of good alliance, if not of fortune : and though Esquires was the generical appellation, yet they were often knights, which last when spoken of individually, were called Knights of the Body."

As will be shown, this is not in fact the case, but is typical of the confusion which seems to surround the subject.

Functions of the knights for the body

editThe knights of the body were often influential local knighted landowners who theoretically reinforced the status both of the king, and of the crown as the final arbiter of justice in the kingdom. They were essentially paid local administrators of the king, who received fees (often/usually/up to 40 marks a year) and robes twice a year (cloth in summer and fur in winter).[f]

The Liber Niger of Edward IV p. 23 "The Kynges Chambyr" allows one mess for "Knights to serve the King of his basen and towel, called for his body" Liber Niger p. 23 goog or Liber Niger p. 23 arch.

Which sounds exactly like the following passage 10 pages later:

- "Knyghts of Household, XII, bachelers sufficiant, and most valient men of that ordre of every countrey [ie shire], and more in numbyr yf hit please the king: whereof iiij to be coninually abydyng and attending uppon the King's person in courte, besides the kervers, as above said, for to serve the king of his bason, or such other servyse as they may do the King, in absence of the kervers, sitting in the King's chaumbre and hall, with persones of lyke service, evryche of them have eatyng in the hall, and taking for his chaumbre at none and nyght, one lofe..."etc. re food[24]

Which means that in this specific case, the Knights of the Household appear to be synonymous with the Knights for the Body... Arrgh

A comprehensive list of the sort of administrative positions they might expect to be appointed to comes from letters patent granted to an esquire who most certainly didn't want to be part of the "central machinery of compulsion":[25]

- 26 March 1442: Exemption, for life, of John Taylboys of Stalyngburgh, co. Lincoln, esquire, from being put on assizes, juries, attaints, recognitions[26] or commission of inquisitions, from being made trier or arrayer thereof, sheriff, escheator, coroner, collector, assessor of tenths, fifteenths or other tallages or subsidies, from being elected knight of the shire, from being appointed justice, keeper of the peace, justice of sewers,[27] justice to make inquisition or other chief justice, constable, trier, arrayer or other bailiff, officer or minister of the king, and from entering the order of knighthood and making fine therefore against his will. By p.s. etc.[28][g]

Beyond this list of standard medieval administrative duties which also included acting as county sheriffs (mainly as tax collectors), sitting on commissions of oyer and terminer, and gaol delivery of accused persons, there were more lucrative Crown offices, such as keeper of various royal parks and other demesnes, constable or steward of a town or castle, Warden (or Keeper) of the Forest of Dean, or Lieutenant of Calais.[citation needed](i.e. you'll need to find specific names from the patent rolls of the men who got these jobs) In many cases these positions had been filled by certain of 'king's knights' going back to Richard II.[31]

Aha! "After 1471 Calais occupied an even more focal position for these purposes than before, its personnel making it almost an 'outward office' of the chamber administered by several household men, with the chamberlain himself at their head as lieutenant, handling the bulk of French and Burgundian business51 and organizing the secret service. The Calais garrison was also the perpetuation of the familia regis as a war-band."[32]

By the mid thirteenth century (temp. Henry III) the crown had arrogated to itself the power to compel judicial, administrative and military service from the ranks of the middling economic ranks of the freeholding population, whatever their tenurial obligations. This burden fell on a wide class of men, worth from £1 to £20 a year or more, including knights, squires, vavasours, valets, and even free peasants, among others.[33] The knights and potential knights, more prominent because of their wealth and greater obligations, are described as the liberi et legales homines of the shires, the "upright, loyal, and knowledgeable" men of each county "whom the crown asked to serve as knights in royal campaigns; to supervise its interests in the counties as sheriffs, coroners, escheators, and foresters; and to perform much of its judicial business as electors and jurors of the grand assize, as the chief members of inquests and perambulations, and as the representatives of the county before the king or central justices."[33]

Mitchell on p. 95, discussing the chamber knights of Richard II, mentions exactly the same positions they filled as did the later knights for the body - diplomatic missions, keepers of parks, forests and castles, as well as "serving the king of his basin" as described in the Black Book. I would take issue with her on this specific point:

- Bannerets, serving the king (Edward IV) as kervers (ie carvers) and cupbearers, are described as "knyghtes of chaumbre", Liber Niger, p. 32; and on p. 33 "In THE NOBLE Edwards dayes worshipfull squires did this service, but now for the more worthy." The expenses of bannerets follow on from this passage, like all the other expenses.

- Knights of Household, next section, p. 33, [NB NOT chamber knights, but who am I to know?] served the king of his basin. And on p. 23 re the King's Chamber, the knights who serve the king of his basin are described as knights for the body.

For example, even in Henry VII's time, a household ordnance states: "if it please the King to have a pallet without his traverse [ie screens, to ensure privacy] there must be two esquires for the body, or else a knight for the body, to lie there or else to lie in the next chamber."[34]

Thus, the knights for the body appear to have combined various aspects of the roles of the bannerets, chamber knights, and the household knights, sometimes referred to by the catch-all term 'king's knights' thanks to the laxness of the translation of the calendars. At various times they were chosen for their military prowess, their diplomatic skills, and their administrative ability. The same jobs need doing throughout the centuries, and it's essentially a question of terminology.

As (hopefully) loyal supporters of the monarch in shires throughout the kingdom, they often held responsible and powerful administrative positions in local government around the country. They were rising/powerful landed/land-owning/renting "gentry", although the term is disputed among historians with their own axe to grind...

Hahaha! This is exactly what Mitchell says about the chamber knights of Richard II: "Their functions were not confined to the physical household, but it was their domestic duties which gave them personal contact with the king and this brought an added dimension to their other activities. That they functioned at the very centre of the household as well a in the wider world made them, simultaneously, the core of the household and the central focus of the greater affinity.[6]

Nevertheless, a number of studies show that monarchs were unwise to trust certain unscrupulous gentry and nobles, however many rewards were heaped on them - e.g. Sir Giles Daubeney.[35]

- "Daubeney's actions also suggest just how tenuous the Tudor hold on power remained until the very end of Henry VII's reign. In particular, they provide another powerful example of the inadequacy of patronage as a device for cementing loyalty. Driven into Henry's arms by the failure of a revolt in which he had apparently participated for purely narrow, territorial reasons, Daubeney later appeared prepared to abandon Henry's son if support for a rival offered greater prospect [of] continued reward. Just as Richard III had found with Buckingham, Henry VII discovered with Stanley (the Lord Chamberlain and Chamberlain) and later Daubeney, that the support of even the most lavishly rewarded subject could not be taken for granted. Indeed, in such cases as these, the main effect of giving a man disproportionate share of favour seems to have been to make him determined to hang on to his privileged position by whatever means, even if that meant betraying the dynasty which from which his good fortune had flowed."[35]

So it seems possible (there's an awful lot of seeming and possibilities in this draft...) that the title 'knight of the body' was - as it were - automatically awarded along with certain of the more important Crown offices - along with fees and robes, and of course the privilege of eating free at court (and some of your retinue as well) and thus mixing with more 'important' people.

- Also: attempt to distinguish between 'below stairs' and 'above stairs' within the royal household. The duties of the knights of the body when at court, or on royal perambulations (rather than in their "own countries") appear to have lain within the regal domestic bustle (familia regis) and its pecking order of valet of the bedchamber, esquire of the household, groom of the stool, etc. See also Order of precedence.

By the time of Henry VII, many positions and privileges were being abused, and Henry required substantial bonds (e.g. cash money, income from lands and sureties from other guarantors) to ensure his officials behaved. (ref below, £10,000 somewhere). To do: find out how local administration in the shires worked under e.g. Elizabeth I... aargh

Well... The sheriffs, personally appointed by the monarch seem to have become the primary way in which the crown exercised its power in the shires, especially in raising and collecting taxes.

- "Certainly, under the Tudors, powers which had once been solely exercised by the sheriff became shared with the lord lieutenant and justices of the peace in a triumvirate of local governance, but the sheriff remained the prime local royal representative for matters of the crown’s personal prerogative rights. Later studies of individual counties and areas showed that Barnes was overly pessimistic about the role of the sheriff. John Morrill, for example, could later write about the Tudor period that he was struck ‘by the slow decline of local power structures built around the noble households, the Liberty and the Manor, and the gradual rise of the power of the institutions in the shires – the lieutenancy, the commission of the peace [and] the revival of the shrievalty’."

- "By way of further emphasis of the responsibility of the sheriff, Elizabeth I decreed that in the absence of a lord lieutenant his powers and responsibilities devolved to the sheriff of the county and particularly so in relation to the militia." (Bullock, p. 193) "It is noticeable that under Elizabeth, the sheriffs were required to carry out tasks of enforcement and administrative governance involving almost entirely individuals rather than communities, whereas under the Stuarts the collection of prerogative revenues meant that the sheriff was enforcing rights against whole communities, through the individuals within them."(Bullock, p. 194) "Sometimes under the prerogative, the Privy Council ordered sheriffs to carry out duties for which they appeared to be unable to find anyone else to be responsible. These might include matters of disorder in the counties, under the sheriffs’ generalised responsibility to keep the peace."(Bullock, p. 195)

‘We have a good king and our imaginations ought to be good to him’: Divided Loyalties Forced on East Midlands Sheriffs, 1580–1640 Richard Bullock in M. Ward, M. Hefferan (eds.), Loyalty to the Monarchy in Late Medieval and Early Modern Britain, c.1400–1688 Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-3-030-37767-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37767-0

"Notoriously this was a lesson [frequently swapping favourites] that Elizabeth also learned, whether from [her father] or from her own experience cannot be judged. We have grown so familiar with the notion of faction in her age that we forget how little the structure of those groupings has been studied...." (GR Elton, Tudor Govt. - Points of contact III The Court, p. 224) - [but this was in 1976...]

At Edward IV's funeral, "The rider’s armour, the horse, and the horse’s accoutrements were payment. Here, the presentation of achievements was cut cleanly away from the armour and horse offering." - Hmm, Would this have been a knight for the body? - No, it was Sir William AParre, the man of arms, or man-at-arms. See funeral of Ed. IV below.

The Royal Funerary and Burial Ceremonies of Medieval English Kings, 1216-1509 Anna M. Duch Doctor of Philosophy thesis University of York May 2016 http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/13700/

Timeline of knights of all sorts in the royal households

editThe knights of the body followed on from previous royal knights, bannerets, chamber knights and household knights (miles noster N), and "king's knights", (noster N miles) (if I have got it right). The esquires and knights of the body did much the same jobs as previous generations of knights, as shown by e.g. Mitchell in her study of Richard II's knightly household. (Mitchell 1998).

Main source:[36]

- Edward I

- an upper rank of ‘household bannerets’ (banneretti hospicii regis)

- and a lower rank of ‘simple household knights’ (milites hospicii regis/milites simplices),

(+ Edward II, vs Isabella & Mortimer, & Edward III)

- Richard II

- a core group of ‘chamber knights’ (milites camere regis),

- a larger number ‘king’s knights’ (milites regis), retained sometimes for life. + livery badges.

- These are often mistaken for knights for the body

- Henrys IV & V

- minimal mentions of knights for the body, maybe as few as four?

- Henry VI

- (two reigns)

- mix of Esquires and at the start of his reign very few Knights of the Body - large household, maybe just lots of hangers-on?

- by c 1450 almost no Knights left ("shorn of almost all his knights of the body")[37] But I don't fink he ever had many anyway. Plus Henry VI lost his reason - by various accounts he just lost the will to do anything at all, a sort of catatonic exhaustion rather than some raving insanity. Any mention of KftBs at the Battle of Towton?

- Edward IV

- (two reigns)

Well, Ed. IV created six knights bachelor at Towton, 29 March 1461[38] See List of Kftbs in Patent Rolls, below.

- After Towton in 1461 there were four KftB: in 1466 there were ten: and at least that in 1471, (Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471, start of Ed IV's 2nd reign...) (Morgan 1973) says 20 - probably 30 in 1483. Maybe read that again.

The Liber Niger of Edward IV (1471) mentions knights "to serve the king for his basin and towel, called for his body" and a a few pages later says that the 12 household knights perform this very function, 4 always to be at court. See refs above. 10 are mentioned in the 1478 ordnance (Harl. MS 642)

Fifteen Messe appointed for the king's chamber

§16. ITEM, we will that there be ordained daylie... two messes for knyghtes for the body, two messe for squiers for our bodie... Myers, p. 201

Which I hadn't noticed before - but they are called 'knights for THE body', and 'squires for OUR body'. Aargh. And this is in English, and not translated from Latin or French.

- "When the household, and the broader court of which it was part, was so quintessentially a matter of personal relationships, the historian can only hope to see what was going on if [s]he has access to private, rather than public, evidence, and for the Yorkist period this is still dishearteningly fragmentary. A particular difficulty is that there are no extant Yorkist chamber accounts, and whole areas of royal activity are consequently invisible." (Horrox 1998, Review, p. 76, below)

- Richard III

who created a few tens of KotBs: and then the Battle of Bosworth (1485)... "A horse! a horse! My kingdom for a horse!" "And all for the want of a horse-shoe nail." And thus

- Henrys VII, & VIII

all of who had lots of KftBs, their numbers growing from 50 to 120 or more.

Growth of size of king's retinue esp. Henry VI which was then limited by parliament i fink; retreat from the hall into the Privy Chamber and then the bed chamber (the king's personal apartments) under Henry VII - somewhat smaller circle - more oppressive rule - greater use of the Star Chamber to counter excessive land claims etc. which assize judges were not competent or powerful enough to deal with.

- "The growth in size of the household under Henry VI and the Yorkists had inflated the numbers of royal body servants to the point where it was impossible for them all to be on intimate terms with the king. Henry VII’s retreat into his Privy Chamber was a reaction against this trend; he maintained the Yorkist use of the household as a means of giving institutional identity to the king's local allies but also re-established alongside it the much older image of the household as a small circle of intimate servants." (Horrox 1988 p. 75)

Review Article: The English Court. The Tudor Court by David Loades. The English Court from the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War by David Starkey Rosemary Horrox The Ricardian Volume 8 issue 101 June 1988 74-78 http://www.thericardian.online/downloads/Ricardian/8-101/06.pdf

- Mini-summary

In some ways the knights of the body were like the old knights of the chamber (milites de camere regis, temp. Richard II) who were somewhat closer and more trusted representatives of the king, more like diplomats who discussed and settled foreign international treaties - as Shelagh Mitchell shows, the chamber knights were also local administrators of one kind or another, much like the knights for the body from the 1450s onwards.[39] On the other hand, the household knights were definitely called knights for the body under Edward IV, so it seems at the moment that the KftBs and the Esquires ftB (not part of this article) combined the functions of all the previous royal knights.

Records of knights for the body in the Patent Rolls etc.

editMostly taken from the Calendars of the Patent Rolls

Include &/or expand Esquire of the Body#Knights of the Body and Talk:Esquire of the Body by Noswall59 & others.

Edward III (1327–1377)

editThe Patent Rolls of Edward III have hundreds of refs to 'king's squires' & 'king's knights', but none to 'knights of the body'. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office : Edward III, 1327-1377

Hmm, Sir William FitzWaryne [fitz Warin] was assigned as knight for the body to Edward III's queen Philippa of Hainault in 1349. (Beltz, "Memorials of the Garter, Edward III & Richard II" p. 96 https://archive.org/details/BeltzGFMemorialsOfTheMostNobleOrderOfTheGarter1841/page/n327/mode/2up ) As far as I can discover, Edward III himself had no knights with this title - the next I have found after this early date is Sir Humphrey Stafford junior of Hook, Dorset (d. 1442) at at Henry V's coronation. See below.

Richard II (1377–1399)

editRichard II retained around 150 king's knights, some of who were retained under Henry IV. In the original manuscript rolls, they were referred to by the king as miles noster, 'our knight'. The translators of the printed calendars of the rolls used the term 'king's knight'. The equivalent back-translation miles regis is not frequently found in contemporary documents.[9]

- The truth, or something like it.

- After 1377 (Richard II's ascension) the term 'the king's knight' began to be used increasingly in the patent rolls. In Richard II's reign there were 149 such knights. They were men of considerable standing within their local community. (Ingamells 1992, vol 1, pp. 10-11) Latin titles pls?

- A question of terminology

The History of Parliament online has a number of entries about MPs who get called 'knights of the body' around the time of Richard II and Henry IV. As far as I can see, the following examples are simply wilful invention.

- Okeover, Sir Philip (d. c.1400), of Okeover, Staffs. and Snelston, Derbys.

- "His grandfather, Sir Roger Okeover (c1288 - 1337), was a Knight of the Body to Edward III."(NB no ref.)

- However, this lengthy article about the Okeovers says he was a Knight for the Shire, but no more than a 'chevaler' or 'bachelor', and no kind of Knight for the Body at all.< ref "An account of the family of Okeover of Okeover, co. Staffs." By Major-General the Hon. George Wrottesley. Collections for a History of Staffordshire, Eds. The William Salt Archaeological Society Volume VII, new series. 1904. pp. 25–40. /ref > But as Hefferan points out, 'bachelerii' was used by Edward III in 1366 to describe his chamber knights, so it's likely that Okeover was one of Richard II's many 'king's knights'. [9]

- "His grandfather, Sir Roger Okeover (c1288 - 1337), was a Knight of the Body to Edward III."(NB no ref.)

- Thornbury, alias Wenlock, Sir John (d.1396), of Little Munden and Bygrave, Herts.

- "By November 1388, he had risen to become a knight of the body to Richard II, and presumably sat as such in the Parliaments of 1390 (Jan.) and 1391.[9]" [ref 9] CPR, 1385–9, p. 535.

- But when you actually look at the CPR Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Richard II, 1385-1389, p. 535 it actually says 'Pardon at the supplication of the king's knight, John Thornebury etc."[40]

- "By November 1388, he had risen to become a knight of the body to Richard II, and presumably sat as such in the Parliaments of 1390 (Jan.) and 1391.[9]" [ref 9] CPR, 1385–9, p. 535.

- "Sir Henry Retford (c.1354-1409), of Castlethorpe and Carlton (c.1354-1409)

- "In November 1393 Retford actually joined the royal household, being retained by Richard II as a knight of the body at an annual fee of 40 marks payable for life[...]

- What is actually written: "November 13 Westminster. Grant, for life, to Henry Retford, knight, because retained to stay for life with the king, for 40 marks a year at the Exchequer. Editorial note: Vacated by surrender and cancelled, because Henry IV granted to him that sum from like issues of the county of Lincoln, 26 February in his second year.CPR, Richard II Vol V, p. 339 - see next entry.

- "Nor was the new King [Henry IV] disposed to show any animosity towards a man of such wide military and administrative experience. Having proved his loyalty to the Lancastrian cause by fighting against the Scots 'and elsewhere', Retford obtained confirmation in February 1401 of his annuity as a knight of the body." (Temp. Henry IV, 1399 - 1413) 'miles pro corpore regis'?

- What is actually written: "Feb. 25. Westminster. Grant for life to Henry de Retford, in consideration of his great expenses on the king's service in Scotland and elsewhere, of 40 marks yearly from the issues of the county of Lincoln, in lieu of a like grant to him at the Exchequer by letters patent of Richard 11, surrendered. By p.s." CPR, Henry IV, Part I, 1399-1401, p. 437

- "In November 1393 Retford actually joined the royal household, being retained by Richard II as a knight of the body at an annual fee of 40 marks payable for life[...]

Well, this type of retaining is specifically discussed by Hefferan:

- "In response [to the passing by the nobles in parliament of the statute of livery and maintenance in 1388, limiting the extent to which livery, both badges and cloth, could be used as a means of retaining], Richard began to retain some of his king’s knights on life contracts. This form of retaining was used only in exceptional circumstances before 1360, as in 1355 when John Staunton was ‘retained by the king for life as a knight of his chamber and one of his household’.[55] After 1387, however, it appears frequently. Seventy men are described as having been retained for life by Richard between 1389 and 1399, while many of those retained prior to this date also moved onto life contracts during this period.56 These life contracts usually took the form of the grant of a royal annuity, attached to which, for the first time, was the specific obligation to act as the king’s formal retainer."[55] CPR, 1353–8, 173 [41]

- "There was also a notable difference in the personnel retained under the three Edwards and Richard II. Given-Wilson identified four main reasons why the men retained as king’s knights under Richard were chosen: "for personal reasons; because they were prominent members of their localities; because he wished to increase his following in particular parts of the country; and because of their military ability".70 [42]

- "Household knights were first and foremost military retainers, whereas king’s knights were designed primarily as a way of augmenting royal authority throughout England’s localities."[43]

- Move ref to stuff about parliament "Thus, by September 1397 there were ‘no fewer than 26 fee’d royal retainers [i.e. king’s knights and king’s esquires] in parliament’, although this was, in part, a result of Richard’s extensive recruitment into his affinity at this time.83 Interestingly, the number of Richard II’s retainers that appeared in parliament was the cause of some controversy. Item 19 of the ‘Record and Process’, which detailed the reasons for Richard’s deposition, accused Richard of sending orders to his sheriffs ‘ordering them to send to parliament as knights of the shire men nominated by the king himself’.84 As with Richard II’s distribution of livery badges in the 1380s, the increased politicisation of royal knights in the fourteenth century was not welcomed by all those in the political community of England."[44]

- "During the course of Edward’s reign, the chamber came to replace the hall as the heart of activity in the royal household, and that this should be reflected in a shift from household knights to chamber knights is unsurprising."[45]

- "The fourteenth century is often characterised as the period in which the knighthood’s military supremacy was fundamentally challenged by the increased emphasis on archers on the battlefield, whose ranks were often drawn from the wealthier peasantry (the yeomanry), and the emergence of professional soldiers.94 This trend would certainly account for why the move from household knights to king’s knights also saw the emergence of a rank of king’s esquires, the majority of whom were drawn from the local gentry and yeomanry, and who were almost indistinguishable from the king’s knights in terms of the way in which they were retained and functioned."[46]

- Mini-summary

It seems, then, that every monarch during the late mediaeval period had his own personal retinue of knights, retained for different reasons according to the circumstances of his reign - some military, some specifically political, some to enhance his general standing in the shires. The "change in the language used to describe royal knights", from 'household knights’ to ‘king’s knights’[47] also appears to be applicable to the change from ‘king’s knights’ to 'knights of the body', since they fulfilled the same sort of functions.

Thus, it seems, the Knights of the Body appear to be the last embodiment of the monarch's personal control over the running of the country.[original research?]

Henry IV (1399–1413)

editNot many hits, but no searchable text: Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... [48] Henry IV. A.D. 1401–1405. https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr00britgoog/page/n4

- 1401–2. Sir John Pilkington was a knight of the body to Henry IV (1399-1413), according to this ref:[49] Hmmm, having read my way through years 1401 and 1402 of CPR 1401-1405 up to p. 146, I find on page 37 that said John Pilkington is merely described as a 'chivaler' or plain knight.[48] There are other references to other 'king's knights', and no other kind of knight: and why he is described as 'knight of the body' is anyone's guess.

Well, having read some more, 'chivaler' appears to be a term applied to retained royal knights,[50] but there's no excuse for calling him a KftB before

But soft... another English term: knight of the royal body...! Sir Thomas Chaworth, (see also below at #Henry V: 1413-1422) is thus described:

Sir Thomas Chaworth argh

edit"Although he must still have been quite young when his father lay dying in December 1398, Thomas Chaworth was none the less appointed to execute his will. In the following November he became a trustee of part of the Longford estates, and he soon began to play an important part in the business of local government. Indeed, in June 1401 Henry IV considered it expedient to retain him as a knight of the royal body at a fee of 40 marks, charged upon the duchy of Lancaster lordship of Gunthorpe." The ref, sadly, appears to be PRO DL42/16, "Duchy of Lancaster, Registers" which means not published.[51]

There are two places with this name: Gunthorpe, Norfolk, in Holt hundred,[52] and the hamlet of Gunthorpe, Rutland.

If Thomas Chaworth was a 'knight of the royal body' in June 1401 (and where is this related?) why is he described as a plain 'chivaler' on 28 September 1401 as paying a fine to the king by mainprise of 2,000 marks on behalf of Thomas Gousill and his wife, widow of Thomas, Duke of Norfolk? Other 'chivalers' are Hugh Shirley,[53] and John de Leek, all of Notts.[54]

And what might be the exact Latin term? Well, if the translation is accurate, the adj. 'royal' (regius) would have the ablative singular form regio since pro takes the ablative, hence the Latin should read miles pro corpore regio ('knight for the royal body') rather than miles pro corpore regis, ('knight of the king's body'). Well I reckon I'm right, but the term miles pro corpore regio just doesn't seem to exist: thus it may perhaps be a fanciful rendering...?

Hmm, the Index to the Close Rolls for the whole of Henry IV's reign has 11 references to Chaworth, (p. 170) but none as knight of the body. Calendar of the close rolls... Henry IV / prepared ... index 1399-1413.

How about the editions in Latin of CPR? ie Calendarium Rotulorum Patentium in Turri Londinensi Calendar of the Patent Rolls in the Tower (in Latin). Printed by command of His Majesty George III in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain. 1802

June 1401 is (according to the table of Regnal Years in Sir Thomas Hardy's invaluable "Syllabus to Rymer's Foedera", Vol 2, p. lvi https://archive.org/details/cu31924007439221/page/n61/mode/1up) 2. Henry IV.

Well, in Calendarium Rotulorum, 2 Henry IV (1399) starts on p. 236...and continues for four sets of patents (Quarta Patent' de Anno 2o Regis Henrici Quarti.) - but despite it being quite entertaining, there appear to be absolutely no hits for KoRB at all. Obviously it is only a very selected Calendar of the contents, as the editorial preface makes clear - lots of entries about abbotts and priories; pontage, pavage, and murage of towns; and royal pardons; but little notice is given to anyone below an earl - e.g. Thomas Percy, 1st Earl of Worcester as lit. seneschal of the kings household per pat' Regis (p. 243).

Sooo, the English version calls him 'steward of the household'. (28 May, CPR as per above, p. 445) NB 'Steward' is an ancient and honourable title.[55]

Thomas Percy, 1 Earl of Worcs.

editWhy do I bother? Well the article about the said Thomas Percy is wafer-thin - doesn't even mention the capture of Richard II at Flint Castle, tho' mentions the Battle of Shrewsbury where the Percys rebelled against Henry IV and lost their lives. There is lots of info about what Percy received from Richard II throughout his reign on p. 110 at CPR, 1 Henry IV part III, and little to show why he did in fact rebel. You actually have to hunt all the way through WP articles about his nephew Harry Hotspur, and Richard II to find how he was deposed. Aargh.

Hmm, 6 July 1401 (Henry IV) - grant to the king's knight Ralph Rochefort [NB Knight for the Body in 1438, Henry VI] the custody all lands late of Robert Coyne and Hugelina his wife, decd. during the minority of their son Robert, 40/- a year etc. p. 446 https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr16offigoog/page/n457/mode/1up

8 February 1401 - commission to Humphrey Stafford, 'chivaler' & others, enquire marriage of John Popham and Walter, Romseye's daughter etc. p. 458 https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr16offigoog/page/n469/mode/1up

lol 30 January 1401 - to John Brook et al., sheriffs of Horsham, to arrest John Bukke, Robert Beykingham, Martin Leson and Thomas 'Jonesservant Bukke', and bring them before the king wherever he may be in England with all speed. By the Chancellor with the assent of William Gascoigne, the king's chief justice, because they are scoffers and gamblers. p. 458 https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr16offigoog/page/n469/mode/1up

Henry V (1413–1422)

editAll 2 vols: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100188846

51 hits for 'king's knight', none for 'knight for the body' Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry V. Vol, 1, A.D. 1413-1416 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c3393878&view=1up&seq=5

47 hits for 'king's knight', none for 'knight for the body' Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry V. Vol, 2, A.D. 1416-1422 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c3393879&view=1up&seq=5

- However, an internet search for "knight of the body to Henry V" shows that there may have been knights of the body at Henry V's coronation in 1413, e.g. Sir Humphrey Stafford junior of Hook, Dorset (d. 1442) ("of the silver hand"):[56]

- Wedgwood, Josiah C. (1919). "Parliament of 1406". In The William Salt Archaeological Society (ed.). Staffordshire Parliamentary History from the earliest times to the present day: Vol. I (1213-1603). (3 volumes). Collections for a History of Staffordshire (3rd series). London: Harrison and Sons, Printers in Ordinary to his Majesty.,

I vaguely wonder if this was a ceremonial appointment for the coronation only, since there seem to be few other references to such knights in, e.g. CPR before Henry VI. I realise there are other sources other than CPR, but they appear to give at least some clue as to how many there were at any period.

Haha!

Ralph Rochefort, 1st mentioned as KftB under Henry VI, - Also earlier a Kt under Henry V - (complete list of knights, Dodd, Appendix 1) - Humphrey Stafford is alphabetical number 58.[57]

(The said) Sir Thomas Chaworth was Knight of the royal body (WHEN?) - but in 1411 he, Leche and others were imprisoned in the Tower for their part in trying to persuade Henry IV to abdicate (lol).[58]

Sir John St. John had begun Henry IV's reign in receipt of a 100 mark annuity, but by 1406 he was retained as a knight of the body by the Prince;[71] the esquire, Hugh Mortimer, also had a £60 annuity from Henry IV, but...[59]

"Of the newcomers to the affinity, some were promoted as a result of their service to the Prince: Sir Humphrey Stafford, Sir Robert Whitney and the esquire Peter Melbourne fall into this category."... "It is now possible to show that Henry's early affinity was not exclusively a military affinity..."[60]

Sir John Oldcastle, heretic and Lollard was turned out of the household before Henry V became king in 1413. [61] And lost his head later anyway.

BUT... nothing about Sir Humphrey Stafford jun. of Hook at all - but [another] Sir Humphrey Stafford received 5 lengths.... [of cloth for Henry IV's funeral I FINK?] [62] - this may be a false lead...? Nothing particularly about Knights for the Body actually present at H V's coronation... even more aargh.

Royal knights in bold in Dod's Appendix - six knights received six lengths of cloth each - Archbishop of Canterbury and other top men received 12 lengths.[63]

- Well, since I'm trying to discover the earliest named KotB's, the obvious thing to do is to transcribe all the names in bold and check 'em out, neh?

Henry VI (1st reign) (1422–1461)

editReigned 1 September 1422 – 4 March 1461.

All 6 vols: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011983740 The on-screen appearance of the Hathitrust website depends on your browser. There doesn't seem to be a box for selecting a page: just edit the url, e.g. seq=240 - NB this is the pdf page number, not the printed page...

Jos. Wedgwood

editIn his History of Parliament (1936), Wedgwood has this to say:

- "Henry VI's household, as reduced in 1455, included two carvers, knights and four Squires of the Body. He had been shorn of almost his Knights of the Body except four. [NB they didn't figure in the household Ordinance - Ordinances of the Household of Henry VI, in the 33rd year of his reign, 1455 Then, or later, Knights of the Body were being paid £50 a year (comparable with £1,500 a year now). Squires got half this, and both had extras. Ninety Knights of the Shire were Squires of the Body, and sixty were at some time also Knights of the Body. Many of the ninety are included in the sixty, for the Esquires got knighted in due course and remained "Of the Body". Most got this Court preferment after, not before, they had been elected to parliament. ... It is curious that the class, style and title died out under the Tudors. The Bodyguard or Yeomen of the Guard, and a profusion of titular rewards, probably replaced both service and attraction."[37]

This confused me for a long time, since there very few KftBs during Henry VI's time. "He had been shorn of almost his Knights of the Body except four" is slightly strange, because I have only found three during the whole of his reign anyway, dating from 1438 - Rochefort, Botiller and Leynthale. Or is he saying that there were considerably more KftBs that I haven't come across yet? (It is also important to remember that Henry VI lost his reason in 1453 for more than a year, and at other later times as well. And when he regained his reason, it was utterly disastrous for the kingdom.) So it appears that Wedgwood was enumerating all the knights of the shire who at any time were ever KftBs, not just temp. Hen VI. There are only 21 or so hits for 'knight of the body' in this 1936 work [History Of Parliament (1439-1509)] But is he also saying that the Esquires of the Body who were knighted remained Esquires "Of the Body", or that they became Knights of the Body...? Many of them were under Henries VII and VIII, so probably the latter.

Knights of the Body under Henry VI

editNB Oops, I failed to make it obvious to which text the following refs are connected: I don't remember whether they refer to the text above or below. A minimum of checking should make it obvious...

Lots of hits for 'king's knight', 0 hits for esquires or knights of or for the body. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry VI. Vol, 1, A.D. 1422-1429 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31158009518282&view=1up&seq=5

47 hits for 'king's knight' 42 hits for 'knight of the shire', neither esquires nor knights of or for the body. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry VI. Vol. 2, A.D. 1429–1436. (1907) https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr01blacgoog/page/n4

5 hits for 'knight for the body', 3 different men:

- 6 January 1438, Kenilworth - Ralph Rochefort, when he first came to serve the king, was granted 100 marks a year, as other knights for the body have, the manors of Benstede and Wauton (Warton?) only providing 50l. a year, the king to make it up by 25 marks a year at the Exchequer of Westminster etc. p. 238

- 10 March 1438 - grant to Ralph Botiller, KftB, of manor of Southam, Glos, and fee farm of Pynnockshyre, £16 7/6 payable by abbot of Hayles, Glos. p. 154

- 8 March 1439 - Grant, for life, to Ralph Botiller, knight for the body, of the office of king's standard bearer, with the accustomed wages, fees, and profits and with 100l. a year from the death of William Haryngton, knight, standard bearer to the king's father, out of the revenues of the commote of Turkelyn, co. Anglesey, by the hands of the sheriff, “raglotiers, ringilds or other ministers or farmers of the said commote. By p.s.

- 30 Dec 1440 - Grant to Botiller and John Noreys esq. to be keeper & captain of Conway - surrendered 1441 to Botiller and Boold - p. 497

- 15 February 1441 - Grant in survivorship to Roland Leynthale (Lenthall) one of the king's knights for the body, and Thomas Stanley, knight, controller of the household, of 40l. yearly from the issues of the manors of Hawardin and Mahaudesdale; in lieu of a grant to the former of a like sum from the manor of Risburgh, surrendered. By p.s. and dated as above. p. 513. (Lenthall went to France with Henry V in 1415, fought at Agincourt, married Margaret, da. of 11th Earl of Arundel)

Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry VI. Vol. 3, A.D. 1436-1441 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt/search?q1=%22knight%20for%20the%20body%22;id=uc1.31158013013296;view=1up;seq=7;start=1;sz=10;page=search;orient=0

- "September 10, 1441. Creation, by advice of the council, of the king's knight Ralph Boteler king's chamberlain, and his heirs male as barons of Sudeley, co. Gloucester ; and grant to them of 200 marks yearly out of the issues of the county of Lincoln. By p.s. etc. Vacated because otherwise in this year.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry VI. Vol. 4, A.D. 1441–1446. https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr00blacgoog/page/n13/mode/1up

- November 21, 1441. Grant in survivorship to Ralph Botiller (Boteler), knight for the body, lord of Westminster. Suddeley, and Bartholomew Boold, esquire, of the keeping and captaincy of the town of Conewaye, North Wales, to hold themselves or by deputy, taking 8d. a day for themselves and 4^. a day for each of eight soldiers, assigned by them for the safe keeping of the town, at the Exchequer of Caernarvon by the hands of the chamberlain there, with all other profits and commodities thereto belonging; in lieu of a grant thereof to the former and John Norreys, esquire, surrendered. By p s. etc. (p. 27) NB This is the only mention of a knight for the body in this volume.

- Boteler's widowed daughter-in-law Lady Eleanor Butler née Talbot was alleged to have made a precontract of marriage with Edward IV, invalidating his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, and legitimising the usurpation of Richard III

Some people really didn't want to be part of the "central machinery of compulsion"[25] at all:

- 26 March 1442: Exemption, for life, of John Taylboys of Stalyngburgh, co. Lincoln, esquire, from being put on assizes, juries, attaints, recognitions[64] or commission of inquisitions, from being made trier or arrayer thereof, sheriff, escheator, coroner, collector, assessor of tenths, fifteenths or other tallages or subsidies, from being elected knight of the shire, from being appointed justice, keeper of the peace, justice of sewers,[27] justice to make inquisition or other chief justice, constable, trier, arrayer or other bailiff, officer or minister of the king, and from entering the order of knighthood and making fine therefore against his will. By p.s. etc. (p. 58)

Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Henry VI. Vol. 4, A.D. 1441–1446. https://archive.org/details/calendarpatentr00blacgoog/page/n37/mode/2up

No hits for knights either of or for the body, 73 hits for 'king's knight', approx 45 'esquire for the body'. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Henry VI. Vol. 5, A.D. 1446–1452. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015031079539;view=1up;seq=5

No hits for knights either of or for the body Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Henry VI. Vol. 6, A.D. 1452–1461. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31158013042337&view=1up&seq=7

Sir Edward Hull

editIn 1448 Sir John Fastolf lost his Norfolk manor of Titchwell to Thomas Wake and Sir Edward Hull, "through Hull's superior influence as Henry VI's knight of the body (by 1445) and membership of the tight circle of royal intimates."(Castor, p. 150)[65]

You simply have to check every single bloody ref, so:

Sir Edward Hull elected to Order of the Garter 7 May 1453 - not installed, (died next year 3 Sept 1453, taken after fighting in France with Shrewsbury at Battle of Chatillon)[66] and anyway he was only knight of the body to Queen Margaret of Anjou at her wedding to Henry VI in 1445[67] NB Lewis says on p. 19 - Wedgwood is wrong about the date of Hull's death. Wedgwood gives full biography. Deffo apparently maybe perhaps only KftB for Margaret of Anjou's wedding to Henry VI in 1445. His inquest names him as "late Esquire of the Body."[68]

So, Hull doesn't appear to have been a Knight of the Body at all.

- See also Arthurian Literature XII edited by James P. Carley, Felicity Riddy - "Malory's Morte d'Arthur", pp. 138-9 https://books.google.com/books?id=2HjgoDCF6ogC&pg=PA139

- Major argh

Arresting mismatch of names of KftBs in CPR thus far, compared to Shaw's Knights of England Vol. 2. At first glance, it would appear that no KftBs up to this point were actually dubbed Knights Bachelor. Obviously Shaw's book appeared in 1903, and nearly 120 years have passed: maybe much more work has been done since then. What about all the king's knights of Richard II etc.? Plenty of hits for them in CPR so far, why so few in Shaw's list? Maybe they weren't necessarily dubbed knights bachelor, merely called to serve in his household? Perhaps another look at Mitchell and Ingamells etc...

Shaw is very specific as to who appears in his list of Knights Bachelor.

- "In accordance with this [variations in two writs of Edward I: the first is described as a writ for the assumption of knighthood; the second is described as a writ of military summons], I argue that the writ for the assumption of knighthood simply established a census or roll or register of persons liable to military duty. It did not affect the status, the social dignity of the soldier (miles). His social status was only enhanced when, later, the added ceremony of dubbing was applied to him. [...] The only conclusion in my mind is that the summons to knighthood was not a summons to a ceremony to a dubbing, but only a summons to the rendering of a military or feudal duty." Thus, "But if this whole body was not so much composed of knights in esse [ie knights in being] as of soldiers (milites) or knights in posse [ie potential knights] then the list of Knights Bachelors of England will be confined to the list of actually dubbed knights. And no more than this is really what all the existing MS. lists give us. The only existing records of the mediaeval Knights Bachelors of England consist of lists of actual dubbings. " (Shaw, Knts of Engl., Vol 1 Intro, pp xlv–xlvi). That this record [MS lists gathered by Shaw and others] (whatever it was) was not on the lines of the later register of knights is shown by the fact that it frequently comprised knights who had not paid their fees to the college. (See note, Vol. II., p. 26, infra.)

But it seems very strange that of the knights of the body I have tentatively listed so far in this main section, apparently none are listed at all by Shaw (I may have missed some of course, and many of his entries include "and many others"). My very first impression is that at least some knights for the body up till this point may not in fact been dubbed bachelor knights, but some other kind of miles, e.g. 'merely' worth a knight's fee: and various points noted in previous sections might tend to support this. Or not. See below, #Who, or what, was a knight?

Edward IV (1st reign) (1461–1470)

editReigned 4 March 1461 – 3 October 1470 (after Battle of Towton)

No hits for 'knight of [or for] the body' 40 hits for 'king's knight, 12 for 'esquire of the body'. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Edward IV. A.D. 1461–1467. (1897) https://archive.org/stream/calendarpatentr14offigoog/calendarpatentr14offigoog_djvu.txt

NB 'of the body' is apparently a slight mistranslation by the editor(s) of the Calendar of the phrase pro corpore regis - I feel it really should be 'for the body', unless the original Latin says de corpore regis. Hmmm. However, the Liber Niger (i fink) actually uses the English phrases 'knight of the body' and 'esquire for the body'. Hmmm.

Well, according to William Shaw (ok, in 1903) Edward IV created six knights bachelor at Towton, March 29 1461: Walter Devereux, William Hastynges, John Howard, sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, Thomas Montgomery, Humphrey Stafford, and Thomas Walgrave.[69]

- After Towton in 1461 there were four KftBs (Morgan 1973): in 1466 there were ten: and at least that in 1471, Morgan says 20 - probably 30 in 1483.

Does Morgan name any of the knights for the body? If so, were they among the six just named? Yes, (Morgan 1973) does name them. Devereux, Hastings, Howard and Montgomery are the four knights for the body, and all were among the six knights bachelor created at Towton.

This is vaguely interesting, or worrying, because these just-named four are the very first milites in William Shaw's list of Knights Bachelor (Knts of Eng., Vol 2) who match up with any of the knights of the body I have previously listed from CPR or other sources up to this point.

- Hmmm, as Shaw says (somewhere above), the records of the Knights Bachelor are the records of those who were actually dubbed knights. See also below in the section 'So who was a knight?' In some cases, basically anyone with a sword (or hauberk) on horseback. As that section shows, in the early mediaeval period, the Barons (i fink I am right) could call anyone a knight, esp. when in military service under them. Such knights were provided by their enfeoffed 'lesser nobles', and could be 'a knight' for just a few months in their entire life.

- {{Thinks}} It may be just possible that in a similar way the king could call anyone 'a knight', even if not dubbed (the belting ceremony may have simply marked their passing into early manhood); all they needed was a sword as a symbol of their authority; and the term 'knight of the body' could have been applied to such men, named by the king as KftB, but never actually dubbed by the king. Hmmm. Only a knight can create another knight. When either barons or lesser knights took men into their military service, would (or could) they have dubbed them themselves? Quite possibly. So you go up to court, already knowing how to behave like a knight,dubbed by your lord 'in his own country', and armed with a sword: is there any need for the king to dub them? Possibly not, since you can't make a knight twice. "Once a knight, always a knight." Nope, "Once a king, always a king, but once a knight is enough ― Ian Fleming, From Russia With Love. </thinks>

- More on Edward IV's first knights of the body

Of Duke Richard's prominent servants, "those surviving most were found a suitable niche in the outer circle of the new affinity as king's knights (William Herbert, Walter Skull), several combining this with service to the duke's widow (John Clay as her chamberlain, Walter Devereux as steward of her lands in Herefordshire)."[70]

"The previous chamberlain John Neville lord Montague was replaced by William Hastings "whose father, a long-serving but unremarkable retainer of Duke Richard, had successfully commended him to the duke at his death in 1455; in blood and land William had no standing of his own but owed his advancement to being attached to Edward when 7th earl of March."[70]

William Port replaced Humphrey Bourchier lord Cromwell (son of Henry Bourchier, 1st Earl of Essex) as treasurer of the chamber. "His antecedents are not out of keeping with those of the four knights of the body, one of whom (William Peche) came from the same Kentish set as John Fogge and John Scott, [these two had been created Knights of the Carpet on 27 June 1461, the day before Edward's coronation.[71]] the rest (William Stanley, John Howard, Thomas Montgomery) from the pre-1460 household of Henry VI with little hiatus thanks to the individual safety-nets formed by their other connexions."[70][h]

By 1466 the original four knights of the body had grown to ten: "three of the extra six (Thomas Burgh, Thomas Bourchier [proably one of the 'Foppish Eleven', see below] and John Fiennes) coming as promotions from within the 1461 chamber, three (William Norris? (but WP article says he was made esquire for the body in 1469 unreffed lol), Gilbert Debenham, Robert Chamberlain) coming from earlier service to Mowbray and Lancaster."[72][i]

"As a group these seven have no peculiar coherence; in origins they were widely diverse and reached Edward's service in quite individual ways; they differed from their fellows only in the degree to which they possessed the features characteristic of their type. Their sartorial exemption was clearly the personal choice of the king from among those whose service to him was for life."[73] Where did the bit about the eleven go...? Found it, see Richard III.

Actually, D.A. Morgan's paper on the Yorkist affinity was one of the very first things I read about the knights for the body, and I mostly skimmed through it. Now I come to re-read it in light of everything else I've read in the meanwhile, it's stuffed full of interesting detail, including the missing Yorkist household accounts (deliberately omitted, not just 'missing' as per Horrox). Is there anything similar for later reigns?

Henry VI (2nd reign) (1470–1471)

editReigned 3 October 1470 - 11 April 1471, 191 days.

Edward IV, (2nd reign) (1471–1483)

editReigned 11 April 1471 – 9 April 1483

- 13 January 1472 - John Pilkington, one of the knights of the body,[74] son? of Sir John Pilkington, who wasn't, see above.[j]

- 3 September 1473 - Humphrey Talbot, knight of the body (CPR 1467-1477 p. 396)

- 1476, Edward IV. Approx 12 genuine refs (at last!) to about 7 knights of the body: Grey, Montgomery, Stanley, Talbot, Ralph Hastings, Trussell, Chamberlain. Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office ... Edward IV and Henry VI A.D. 1467–1477. (1900) https://archive.org/stream/calendarpatentr05blacgoog/calendarpatentr05blacgoog_djvu.txt

"The inscription tells us that in the 1475 invasion of France he [Sir Humph. Talbot, Marshal of Calais] contributed for the first quarter 10 men-at-arms and 100 archers (for which he was paid £298 0s 6d). At that time he was a Knight of the Royal Body, but is not described as a Banneret." https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/tag/sir-humphrey-talbot/ A talbot hound for a Talbot knight....? Murrey and Blue. But a blog.

Foedera - Index to Hardy's Syllabus (Vol. 3): Two mentions of 'Knight of the Body', pp. 706 & 741