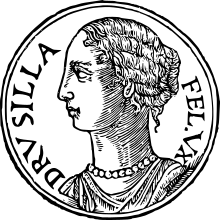

Julia Drusilla (Greek: Δρούσιλλα; born AD 38) was a daughter of Herod Agrippa (the last king of ancient Roman Judaea) and Cypros. Her siblings were Berenice, Mariamne, and Herod Agrippa II.[1] Her son Agrippa was one of the few people known by name to have died in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.[2]

Life

editFirst marriage

editHer father King Herod Agrippa had betrothed her to Gaius Julius Archelaus Antiochus Epiphanes, first son of King Antiochus IV of Commagene,[3] with a stipulation from Agrippa that Epiphanes should embrace the Jewish religion,[4] but the marriage had not been contracted on her father's sudden death in 44. According to Josephus, on Agrippa's death the populace "cast such reproaches upon the deceased as are not fit to be spoken of; and so many of them as were then soldiers, which were a great number, went to his house, and hastily carried off the statues of [Agrippa I]'s daughters, and all at once carried them into the brothels, and when they had set them on the brothel roofs, they abused them to the utmost of their power, and did such things to them as are too indecent to be related".[5]

Once her brother Herod Agrippa II had been assigned the tetrarchy of Herod Philip I (along with Batanea, Trachonites and Abila) in around 49/50, he broke off her engagement and gave her in marriage to Gaius Julius Azizus, priest king of the Emesene dynasty, who had consented to be circumcised.[4]

Marriage to Antonius Felix

editIt appears that it was shortly after her first marriage was contracted that Antonius Felix, the Roman procurator of Judea, met Drusilla, probably at her brother's court (Berenice, the elder sister, lived with Agrippa II at this time, and it is thought Drusilla did too). Felix was reportedly struck by her great beauty and determined to make her his (second) wife. In order to persuade her—a practising Jew—to divorce her husband and marry him—a pagan—he sent an emissary to plead for him.

But for the marriage of Drusilla with Azizus, it was in no long time afterward dissolved upon the following occasion: While Felix was procurator of Judea, he saw this Drusilla, and fell in love with her;[6] for she did indeed exceed all other women in beauty; and he sent to her a person whose name was Simon[7] (Note: in some manuscripts, Atomos), a Jewish friend of his, by birth a Cypriot, who pretended to be a magician. Simon endeavored to persuade her to forsake her present husband, and marry Felix; and promised, that if she would not refuse Felix, he would make her a happy woman. Accordingly she acted unwisely and, because she longed to avoid her sister Berenice's envy (for Drusilla was very ill-treated by Berenice because of Drusilla's beauty) was prevailed upon to transgress the laws of her forefathers, and to marry Felix; and when he had had a son by her, he named him Agrippa. But after what manner that young man, with his wife [or "with the woman"], perished at the conflagration of the mountain Vesuvius, in the days of Titus Caesar, shall be related hereafter.[8]

She was about 22 when she appeared at Felix's side, during Paul the Apostle's captivity at Caesarea—the Book of Acts 24:24 reports that "Several days later Felix came [back into court] with his wife Drusilla, who was a Jewess." The Book of Acts gives no further information on her subsequent life, but Josephus states that they had a son named Marcus Antonius Agrippa. Their son perished with most of the populations of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Josephus says "σὺν τῇ γυναικὶ", which has been interpreted as "with his wife", or alternatively "with the woman", namely Drusilla.[9]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Jacobson, David (2 July 2019). Agrippa II: The Last of the Herods. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-82357-2.

- ^ Curran, John (23 September 2014). "Philorhomaioi: The Herods between Rome and Jerusalem". Journal for the Study of Judaism. 45 (4–5): 493–522. doi:10.1163/15700631-12340097. ISSN 1570-0631.

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, xix. 9. § 1.

- ^ a b Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, xx.7.1

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, xix. 9. 1 and xx.7.1

- ^ Or, "took a lust for the woman".

- ^ Atomos in some manuscripts

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, xx.7.2. In Greek: Διαλύονται δὲ τῇ Δρουσίλλῃ πρὸς τὸν Ἄζιζον οἱ γάμοι μετ᾽ οὐ πολὺν χρόνον τοιαύτης ἐμπεσούσης αἰτίας: καθ᾽ ὃν χρόνον τῆς Ἰουδαίας ἐπετρόπευε Φῆλιξ θεασάμενος ταύτην, καὶ γὰρ ἦν κάλλει πασῶν διαφέρουσα, λαμβάνει τῆς γυναικὸς ἐπιθυμίαν, καὶ Ἄτομον ὀνόματι τῶν ἑαυτοῦ φίλων Ἰουδαῖον, Κύπριον δὲ τὸ γένος, μάγον εἶναι σκηπτόμενον πέμπων πρὸς αὐτὴν ἔπειθεν τὸν ἄνδρα καταλιποῦσαν αὐτῷ γήμασθαι, μακαρίαν ποιήσειν ἐπαγγελλόμενος μὴ ὑπερηφανήσασαν αὐτόν. ἡ δὲ κακῶς πράττουσα καὶ φυγεῖν τὸν ἐκ τῆς ἀδελφῆς Βερενίκης βουλομένη φθόνον αὑτῇ διὰ τὸ κάλλος παρεκάλει παρ᾽ ἐκείνης οἰόμενος οὐκ ἐν ὀλίγοις ἔβλαπτεν, παραβῆναί τε τὰ πάτρια νόμιμα πείθεται καὶ τῷ Φήλικι γήμασθαι. τεκοῦσα δ᾽ ἐξ αὐτοῦ παῖδα προσηγόρευσεν Ἀγρίππαν. ἀλλ᾽ ὃν μὲν τρόπον ὁ νεανίας οὗτος σὺν τῇ γυναικὶ κατὰ τὴν ἐκπύρωσιν τοῦ Βεσβίου ὄρους ἐπὶ τῶν Τίτου Καίσαρος χρόνων ἠφανίσθη, μετὰ ταῦτα δηλώσω.

- ^ Jewish Antiquities, xx.7.2. See quote above. Josephus says he will relate the incident later, but there is no further mention of it in the extant work.

References

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Drusilla". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.