Dunnockshaw or Dunnockshaw and Clowbridge is a civil parish in the borough of Burnley, in Lancashire, England. The parish is situated between Burnley and Rawtenstall. According to the United Kingdom Census 2011, the parish has a population of 185.[1]

| Dunnockshaw | |

|---|---|

Sunset at Clowbridge Reservoir | |

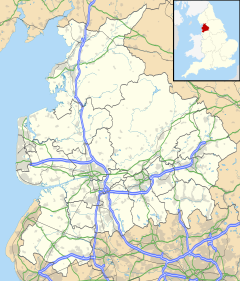

Location within Lancashire | |

| Area | 1.02 sq mi (2.6 km2) [1] |

| Population | 185 (2011)[1] |

| • Density | 181/sq mi (70/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SD821280 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BURNLEY |

| Postcode district | BB11 |

| Dialling code | 01282 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

It contains the hamlets of Clowbridge and Dunnockshaw, both located on the A682 road. Clowbridge Reservoir is situated in the east of parish on the boundary with Rossendale. The reservoir, operated by United Utilities, is used as a location for water sports. It was built in 1866 resulting in the de-population of the village of Gambleside.

The parish adjoins the Burnley parishes of Hapton and Habergham Eaves and the Gambleside and Loveclough areas of the Borough of Rossendale.

History

editThe name Dunnockshaw probably comes from the words "dunnock", a small bird known locally as a hedge sparrow, and "shaw" (Old English sceaga), a small woodland or thicket.[2]

Dunnockshaw was one of the booths in the Forest of Rossendale. By the 17th century it was the property of the Towneleys of Hurstwood, probably by inheritance from the Ormerod family.[3] The road that is now the A682 was built by the Burnley and Edenfield Turnpike Trust following a 1795 act of Parliament, to improve transport to Manchester.[4]

The three-storey Oak Mill was erected as a combined spinning and weaving mill in 1840 for a colliery owner and quarry master named Peter Pickup. Subsequently, extended, a fire in 1907 gutted much of the building and the interior was reconstructed. It has not been used by the textile industry since at least the early 1970s, when glass fibre products began being produced here.[5]

Burnt Hills Colliery was owned by the Executors of John Hargreaves, operating from the 1840s until official closure in 1920. It worked the Upper and Lower Mountain mines[a] and in 1842 employed 20 men and boys. A surface tramroad connected to Porters Gate Colliery on the north side of the hill by about 1863. In 1880 the tramroad was extended from Porters Gate to connect to the system at Hapton Valley Colliery, creating an almost 4.8-kilometre (3 mi) long route that reached the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Gannow in Burnley. In 1892 it had two 44-metre (48 yd) shafts with a single-cylinder winding engine along with an underground engine which drove a 3.2-kilometre (2 mi) long haulage system that raised the coal through a surface drift. It is uncertain when production stopped, as after 1910 any output was recorded with Hapton Valley. The coal staithe next to Cotton Row and tramroad continued to operate for some time after 1920.[6]

Permission to construct the reservoir at Clowbridge—historically known as the Hapton Reservoir—on the Limy Water, was contained in the 1853 that act created the Haslingden and Rawtenstall Waterworks Company.[7][8] 18 months after starting construction under the supervision of Thomas Hawksley, work was suspended as the company expended all its capital. After a three-year hiatus work recommenced under the direction of Joseph Jackson, and although nearing completion in 1863, a series of landslips meant work was not completed until August 1865. The total cost was at least £46,547 (the equivalent of £5.62 million as of 2024[b]).[9] Later taken-over by the Bury Corporation, in 1898 it was recorded to cover an area of 88 acres (36 ha) and have a capacity of 350 million imperial gallons (1.6 million cubic metres; 1.6 billion litres). Some of its water supply is pumped from an old mineshaft belonging to the Gambleside Colliery. At the end of the 19th century a total population of 110 lived in 22 houses within the "gathering ground" of the reservoir, with Cronkshaw Hill farmhouse located very close to the shoreline. Concerns over pollution lead to increased restrictions on farming in the area.[10]

During World War II a Starfish site bombing decoy was constructed on Hameldon hill near Heights Farm, part of a network designed to protect Accrington.[11] Its site is protected as a Scheduled monument.[12]

Governance

editDunnockshaw was once a township in the ancient parish of Whalley. This became a civil parish in 1866, forming part of the Burnley Rural District from 1894. At that time the Clowbridge area, previously part of Hapton,[c] transferred to Dunnockshaw but a detached area on Hameldon called Dunnockshaw Close moved to Hapton in 1935.[14] Since 1974 Dunnockshaw has formed part of the Borough of Burnley. Another change which took effect at the start of 1983, transferred part of Habergham Eaves lying west of Limey Lane into this civil parish.[15]

Along with Habergham Eaves and a small part of Burnley, the parish forms the Coalclough with Deerplay ward of the borough council.[16] The ward elects three councillors, currently Gordon Birtwistle and Howard Baker of the Liberal Democrats, and Bill Brindle (Labour).[17] The parish is represented on Lancashire County Council as part of the Padiham & Burnley West division, represented since 2017 by Alan Hosker (Conservative).[18]

The Member of Parliament for Burnley, the constituency into which the parish falls, is Oliver Ryan of the Labour Party, who was first elected in 2024.

Demography

editAccording to the United Kingdom Census 2011, the parish has a population of 185, a decrease from 212 in the 2001 census. This represents a decline of 14.6% over ten years. The parish has an area of 264 hectares (1.02 sq mi; 2.64 km2), giving a population density of 0.70 inhabitants per hectare (180/sq mi; 70/km2).[1][19]

In 2011 the average (mean) age of residents was 42.9 years, with a roughly even distribution between males and females. The racial composition was 98.9% White (all White British) with just two people of mixed ethnic groups. 67% reported their religion as Christian. 71.9% of adults between the ages of 16 and 74 were classed as economically active and in work.[1]

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | 2011 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 518 | 517 | 489 | 429 | 331 | 309 | 212 | 185 | |||||||||||||

| [14][19][1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

Media gallery

edit-

Clowbridge

-

A682 Burnley Road

-

New Laithe farm

-

Oak Mill, Dunnockshaw

-

Met Office north-west England weather radar on Hameldon Hill

See also

editReferences

editNotes

- ^ In this part of Lancashire a coal seam is referred to as a mine and the coal mine as a colliery or pit.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ The old township boundary with Hapton broadly followed Limy Water and is today beneath Clowbridge Reservoir.[13]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Dunnockshaw Parish (E04005133)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1922). The place-names of Lancashire. Manchester University Press. pp. 16, 100. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Farrer, William; Brownbill, John, eds. (1911). The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster Vol 6. Victoria County History. Constable & Co. p. 514. OCLC 832215477. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "BURNLEY: HISTORIC TOWN ASSESSMENT REPORT" (PDF). Lancashire County Council. 2005. p. 66. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Oak Mill (1585454)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Nadin, Jack (1997), British Mining No. 58 The Coal Mines of East-Lancashire, Northern Mine Research Society, pp. 46, 92, 121, ISBN 0901450480

- ^ "Local and Personal Acts Declared Public (1853)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 20 August 1853. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "No. 21385". The London Gazette. 26 November 1852. pp. 3368–3369.

- ^ "Visit to Goodshaw Chapel and Gambleside, Rossendale". www.chorleyhistorysociety.co.uk. 15 July 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Bruce Low, R (1898). Report on the sources and circumstances of the water service provided by the Bury Corporation... H.M. Stationery Office. pp. 94, 102. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Historic England. "STARFISH BOMBING DECOY SF35E (1360177)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ *Historic England. "Hameldon Hill World War II bombing decoy, 390m north of Heights Farm (1020666)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Lancashire and Furness (Map) (1st ed.). 1 : 10,560. County Series. Ordnance Survey. 1848.

- ^ a b "Dunnockshaw Tn/CP through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "The Burnley (Parishes) Order 1982" (PDF). LGBCE. 29 September 1982. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Wards and parishes map". MARIO. Lancashire County Council. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Your Councillors". burnley.moderngov.co.uk. Burnley Borough Council. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "County Councillors by Local Community". Lancashire County Council. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ a b UK Census (2001). "Local Area Report – Dunnockshaw Parish (30UD003)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

External links

edit- Map of Dunnockshaw and Clowbridge parish boundary Today - Lancashire County Council

- Map of Dunnockshaw parish boundary circa 1850

- Dunnockshaw Township - British History Online

- Clowbridge Reservoir & Dunnockshaw Community Woodland at United Utilities Website Archived 2 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine