United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri

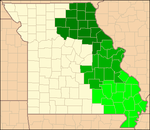

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri (in case citations, E.D. Mo.) is a trial level federal district court based in St. Louis, Missouri, with jurisdiction over fifty counties in the eastern half of Missouri. The court is one of ninety-four district-level courts which make up the first tier of the U.S. federal judicial system. Judges of this court preside over civil and criminal trials on federal matters that originate within the borders of its jurisdiction. It is organized into three divisions, with court held in St. Louis, Hannibal, and Cape Girardeau.

| United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri | |

|---|---|

| (E.D. Mo.) | |

| |

| |

| Location | Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse More locations |

| Appeals to | Eighth Circuit |

| Established | March 3, 1857 |

| Judges | 9 |

| Chief Judge | Stephen R. Clark |

| Officers of the court | |

| U.S. Attorney | Sayler A. Fleming (acting) |

| U.S. Marshal | John D. Jordan |

| moed.uscourts.gov | |

The court was formed when the District of Missouri was divided into East and West in 1857, and its boundaries have changed little since that division.[1] In its history it has heard a number of important cases that made it to the United States Supreme Court, covering issues related to freedom of speech, abortion, property rights, and campaign finance. There are currently nine active judges, five judges in senior status, and seven magistrate judges attached to the court.

As of December 31, 2020[update], the acting United States attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri is Sayler A. Fleming.[2]

Mandate and jurisdiction

editAs a United States district court, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri conducts civil trials and issues orders. The cases it hears concern either federal question jurisdiction, where a federal law or treaty is applicable, or diversity jurisdiction, where parties are domiciled in different states. The court also holds criminal trials of persons charged with violations of federal law. Appeals from cases brought in the Eastern District of Missouri are heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (except for patent claims and claims against the U.S. government under the Tucker Act, which are appealed to the Federal Circuit). These cases can then be appealed to the United States Supreme Court.[3]

The Court is based in St. Louis but is organized into three divisions: Eastern, Northern, and Southeastern.

The court for the Eastern division is held in downtown St. Louis, in the Thomas F. Eagleton United States Courthouse, where the St. Louis Clerk's Office is located. It covers the counties of Crawford, Dent, Franklin, Gasconade, Jefferson, Lincoln, Maries, Phelps, Saint Charles, Saint Francois, Saint Louis, Warren, Washington, and the independent City of St. Louis.

The Northern division is based in Hannibal, Missouri, but its office is unstaffed unless court is being held there. It covers the counties of Adair, Audrain, Chariton, Clark, Knox, Lewis, Linn, Macon, Marion, Monroe, Montgomery, Pike, Ralls, Randolph, Schuyler, Shelby, and Scotland.

The Southeastern division is based at Cape Girardeau. Its courthouse is named for Rush Limbaugh Sr.[4] That division's jurisdiction covers Bollinger, Butler, Cape Girardeau, Carter, Dunklin, Iron, Madison, Mississippi, New Madrid, Pemiscot, Perry, Reynolds, Ripley, Sainte Genevieve, Scott, Shannon, Stoddard, and Wayne counties.

History

editOrigins

editMissouri was admitted as a state on August 10, 1821, and the United States Congress established the United States District Court for the District of Missouri on March 16, 1822.[1][5][6] The District was assigned to the Eighth Circuit on March 3, 1837.[1][7] Congress subdivided it into Eastern and Western Districts on March 3, 1857.[1][8] and has since made only small adjustments to the boundaries of that subdivision. The division was prompted by a substantial increase in the number of admiralty cases arising from traffic on the Mississippi River, which had followed an act of Congress passed in 1845 and upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1851, extending federal admiralty jurisdiction to inland waterways.[9] These disputes involved "contracts of affreightment, collisions, mariners' wages, and other causes of admiralty jurisdiction", and litigants of matters arising in St. Louis found it inconvenient to travel to Jefferson City for their cases to be tried.[9]

When the District of Missouri was subdivided, Robert William Wells, who was the sole judge serving the District of Missouri at the time of the division, was reassigned to the Western District,[10] allowing President Franklin Pierce to appoint Samuel Treat as the first judge for the Eastern District of Missouri.[11] The court was initially authorized to meet in St. Louis, which had previously been one of the two authorized meeting places of the District Court for the District of Missouri.[12] It met for a time at the landmark courthouse shared with Missouri state courts, which was the tallest building in the state during that period. For the first thirty years of its existence, the court was primarily concerned with admiralty and maritime cases, including maritime insurance claims.[9]

Civil War and aftermath

editWithin a few years of the court's establishment, the American Civil War erupted, and Missouri was placed under martial law.[13] Missouri was a border state with sharply divided loyalties among its citizenry, resulting in the imposition of stern controls from the Union government, including the imprisonment of large number of Missouri militiamen.[13] When the District, by the hand of Judge Treat, issued a writ of habeas corpus for the release of one of them, Captain Emmett MacDonald, Union commanding general William S. Harney refused, asserting that he had to answer to a "higher law".[13] A substantial portion of the court's docket in this period came from tax cases:[9]

when the Civil War came it brought in its train a new class of cases, arising from the violation of treasury regulations, and proceedings to enforce the internal revenue law in all its complex and multiplied divisions and subdivisions. When whisky and tobacco, and net income, and gross receipts, and manufactories, and occupations, and legacies, and bonds, and notes, and conveyances, and drugs and medicines, and other innumerable things, were taxed by the Federal government, and each one had a separate code of laws of its own ...[9]

The court, in this time, also tried numerous criminal cases arising from efforts to evade the tax laws through smuggling and fraud.[9] Following the Civil War, and in response to the economic disruption it had caused, Congress enacted the Bankruptcy Act of 1867.[14] Between its enactment and its subsequent repeal in 1878, the Act caused "countless controversies" arising in bankruptcy to be brought before the District Court.[9] Despite the turmoil inflicted by the Civil War, Missouri experienced a population boom, becoming the fifth largest state in the U.S. by 1890, and having a busy court docket which reflected this population growth.[15]

Further division and expansion

editIn 1887 a Congressional Act divided the Eastern District into the Northern and Eastern Divisions of the Eastern District. The courts of the Eastern Division continued to be held at the U.S. Custom House and Post Office in St. Louis,[16] while the courts of the Northern Division were moved to the U.S. Post Office at Hannibal, Missouri, where they met until 1960.[12][17] These two courts, along with the four courts of the Western District, made six courts for the state, and at the time no other state had so many separate federal courts.[18] The district has since been further divided into the Eastern, Northern, and Southeast divisions.

In 1888, Audrain County, Missouri, was moved from the Eastern to the Western District. In 1897, it was moved back to the Eastern district.[18] In 1891, the United States circuit courts were eliminated in favor of the new United States courts of appeals. When the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit heard its first case, on October 12, 1891, the presiding judge Henry Clay Caldwell was joined by two district court judges from within the jurisdiction of the Circuit. One of those was Amos Madden Thayer of the Eastern District of Missouri.[15] Thayer would later be appointed to the Eight Circuit in his own right.

The court was authorized to meet in Cape Girardeau beginning in 1905,[12] and from 1910 to 1920 was additionally authorized to meet in Rolla, Missouri.[12] On September 14, 1922,[19] an additional temporary judgeship was authorized for each district of Missouri, and on August 19, 1935,[20] these temporary judgeships were made permanent. Additional judgeships were added to the Eastern District in 1936, 1942, 1970, 1978, and 1984, and two were added in 1990, bringing the Eastern District to its current total of nine judges.

The court continued to meet at the U.S. Custom House and Post Office until 1935,[16] and then moved to the United States Court House and Custom House in St. Louis.[21] In 2001 it moved to the Thomas F. Eagleton United States Courthouse, the largest courthouse in the United States.[22]

The 2000 census reported that the district had a population of nearly 2.8 million, ranking 38th in population among the 90 U.S. judicial districts.[23]

Jean Constance Hamilton, appointed by George H. W. Bush in 1990, was the first female judge appointed to the District. The first African American to serve was Clyde S. Cahill Jr., who was appointed by Jimmy Carter in 1980. Over the history of the District, five of its judges have been elevated to the Eighth Circuit – Elmer Bragg Adams, John Caskie Collet, Charles Breckenridge Faris, Amos Madden Thayer and William H. Webster.

Notable cases

editDuring the Great Depression, three important United States Supreme Court cases were decided which determined the constitutionality of New Deal measures, one of which originated in the Eastern District of Missouri. The case, originally filed as Norman v. B & O Railroad,[24] reached the Supreme Court along with two cases filed in the United States Court of Claims, under the single heading of the Gold Clause Cases.[15] The Supreme Court upheld the determination of the trial court judge, Charles Breckenridge Faris, who found that Congress had the power to prohibit parties from contracting for payment in gold.

In 1976, the court heard the original proceedings in Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth,[25] a case that challenged several Missouri state regulations regarding abortion. The case was eventually appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which reaffirmed the right to abortion and struck down certain restrictions as unconstitutional.

Due to a school desegregation suit in 1972, the court required St. Louis to accept a busing plan in 1980. Judge William L. Hungate declared that a mandatory plan would go into effect unless other arrangements were made to adhere to the terms of the suit. In 1983, an unprecedented voluntary busing plan was put into place, integrating the schools without a mandated plan being required.

In Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier,[26] a case that started in Missouri's Eastern District went before the United States Supreme Court in 1988, it was held that public school curricular student newspapers are subject to a lower level of First Amendment protection. Another First Amendment case in public schools came up in 1998, when E.D. Mo. heard Beussink v. Woodland R-IV School District.[27] Judge Rodney W. Sippel ruled that the school violated a student's rights by sanctioning him for material he posted on his website. This case has been widely cited in higher courts.[28]

In the 2000s, two more notable cases originated in this District and were heard by the United States Supreme Court. Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC[29] upheld state limits on campaign contributions to state offices, and Sell v. United States[30] imposed stringent limits on the right of a lower court to order the forcible administration of antipsychotic medication to a criminal defendant who had been determined to be incompetent to stand trial for the sole purpose of making him competent and able to be tried. Several notable antitrust cases originated in this district including Brown Shoe Co. v. United States[31] (preventing a merger between two shoe wholesalers which would have reduced competition in the region), and United Shoe Machinery Corp. v. United States[32] (prohibiting certain long-term leases of manufacturing equipment). Another important case brought in the district, Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co.,[33] involved the right of companies to maintain trade secrets under Missouri law in the face of federal regulations requiring disclosure of pesticide components.

Current judges

editAs of July 31, 2024[update]:

| # | Title | Judge | Duty station | Born | Term of service | Appointed by | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Chief | Senior | ||||||

| 41 | Chief Judge | Stephen R. Clark | St. Louis | 1966 | 2019–present | 2022–present | — | Trump |

| 35 | District Judge | Henry Autrey | St. Louis | 1952 | 2002–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 39 | District Judge | Brian C. Wimes[Note 1] | none[Note 2] | 1966 | 2012–present | — | — | Obama |

| 42 | District Judge | Sarah Pitlyk | St. Louis | 1977 | 2019–present | — | — | Trump |

| 43 | District Judge | Matthew T. Schelp | St. Louis | 1970 | 2020–present | — | — | Trump |

| 44 | District Judge | vacant | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 45 | District Judge | vacant | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 46 | District Judge | vacant | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 47 | District Judge | vacant | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 21 | Senior Judge | Edward Louis Filippine | inactive | 1930 | 1977–1995 | 1990–1995 | 1995–present | Carter |

| 27 | Senior Judge | Jean Constance Hamilton | inactive | 1945 | 1990–2013 | 1995–2002 | 2013–present | G.H.W. Bush |

| 31 | Senior Judge | Catherine D. Perry | St. Louis | 1952 | 1994–2018 | 2009–2016 | 2018–present | Clinton |

| 32 | Senior Judge | E. Richard Webber | inactive | 1942 | 1995–2009 | — | 2009–present | Clinton |

| 33 | Senior Judge | Nanette Kay Laughrey[Note 1] | none[Note 3] | 1946 | 1996–2011 | — | 2011–present | Clinton |

| 34 | Senior Judge | Rodney W. Sippel[Note 1] | St. Louis | 1956 | 1997–2023 | 2016–2022 | 2023–present | Clinton |

| 36 | Senior Judge | Stephen N. Limbaugh Jr. | Cape Girardeau | 1952 | 2008–2020 | — | 2020–present | G.W. Bush |

| 37 | Senior Judge | Audrey G. Fleissig | St. Louis | 1955 | 2010–2023 | — | 2023–present | Obama |

| 38 | Senior Judge | John Andrew Ross | St. Louis | 1954 | 2011–2023 | — | 2023–present | Obama |

Vacancies and pending nominations

edit| Seat | Prior judge's duty station | Seat last held by | Vacancy reason | Date of vacancy | Nominee | Date of nomination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | St. Louis | Rodney W. Sippel | Senior status | January 28, 2023 | – | – |

| 2 | Audrey G. Fleissig | April 14, 2023 | – | – | ||

| 9 | John Andrew Ross | June 9, 2023 | – | – | ||

| 5 | Ronnie L. White | Retirement | July 31, 2024 | – | – |

Former judges

edit| # | Judge | State | Born–died | Active service | Chief Judge | Senior status | Appointed by | Reason for termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samuel Treat | MO | 1815–1902 | 1857–1887 | — | — | Pierce | retirement |

| 2 | Amos Madden Thayer | MO | 1841–1905 | 1887–1894 | — | — | Cleveland | elevation to 8th Cir. |

| 3 | Henry Samuel Priest | MO | 1853–1930 | 1894–1895 | — | — | Cleveland | resignation |

| 4 | Elmer Bragg Adams | MO | 1842–1916 | 1895–1905[Note 1] | — | — | Cleveland | elevation to 8th Cir. |

| 5 | Gustavus A. Finkelnburg | MO | 1837–1908 | 1905–1907[Note 2] | — | — | T. Roosevelt | resignation |

| 6 | David Patterson Dyer | MO | 1838–1924 | 1907–1919 | — | 1919–1924 | T. Roosevelt | death |

| 7 | Charles Breckenridge Faris | MO | 1864–1938 | 1919–1935 | — | — | Wilson | elevation to 8th Cir. |

| 8 | Charles B. Davis | MO | 1877–1943 | 1924–1943 | — | — | Coolidge | death |

| 9 | George Moore | MO | 1878–1962 | 1935–1962 | 1948–1959 | 1962 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 10 | John Caskie Collet | MO | 1898–1955 | 1937–1947[Note 3] | — | — | F. Roosevelt | elevation to 8th Cir. |

| 11 | Richard M. Duncan | MO | 1889–1974 | 1943–1965[Note 3] | — | 1965–1974 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 12 | Rubey Mosley Hulen | MO | 1894–1956 | 1943–1956 | — | — | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 13 | Roy Winfield Harper | MO | 1905–1994 | 1947[Note 4][Note 3] 1947–1948[Note 5][Note 3] 1948–1971[Note 6][Note 3] |

1959–1971 | 1971–1994 | Truman Truman Truman |

death |

| 14 | Randolph Henry Weber | MO | 1909–1961 | 1957–1961 | — | — | Eisenhower | death |

| 15 | James Hargrove Meredith | MO | 1914–1988 | 1962–1979 | 1971–1979 | 1979–1988 | Kennedy | death |

| 16 | John Keating Regan | MO | 1911–1987 | 1962–1977 | — | 1977–1987 | Kennedy | death |

| 17 | William Robert Collinson | MO | 1912–1995 | 1965–1980[Note 3] | — | 1980–1995 | L. Johnson | death |

| 18 | William H. Webster | MO | 1924–present | 1970–1973 | — | — | Nixon | elevation to 8th Cir. |

| 19 | Harris Kenneth Wangelin | MO | 1913–1987 | 1970–1983[Note 3] | 1979–1983 | 1983–1987 | Nixon | death |

| 20 | John Francis Nangle | MO | 1922–2008 | 1973–1990 | 1983–1990 | 1990–2008 | Nixon | death |

| 22 | William L. Hungate | MO | 1922–2007 | 1979–1991 | — | 1991–1992 | Carter | retirement |

| 23 | Clyde S. Cahill Jr. | MO | 1923–2004 | 1980–1992 | — | 1992–2004 | Carter | death |

| 24 | Joseph Edward Stevens Jr. | MO | 1928–1998 | 1981–1995[Note 3] | — | 1995–1998 | Reagan | death |

| 25 | Stephen N. Limbaugh Sr. | MO | 1927–present | 1983–1996[Note 3] | — | 1996–2008 | Reagan | retirement |

| 26 | George F. Gunn Jr. | MO | 1927–1998 | 1985–1996 | — | 1996–1998 | Reagan | death |

| 28 | Donald J. Stohr | MO | 1934–2015 | 1992–2006 | — | 2006–2015 | G.H.W. Bush | death |

| 29 | Carol E. Jackson | MO | 1952–present | 1992–2017 | 2002–2009 | — | G.H.W. Bush | retirement |

| 30 | Charles Alexander Shaw | MO | 1944–2020 | 1993–2009 | — | 2009–2020 | Clinton | death |

| 40 | Ronnie L. White | MO | 1953–present | 2014–2024 | — | — | Obama | retirement |

- ^ Recess appointment; formally nominated on December 4, 1895, confirmed by the United States Senate on December 9, 1895, and received commission the same day.

- ^ Recess appointment; formally nominated on December 5, 1905, confirmed by the Senate on December 12, 1905, and received commission the same day.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jointly appointed to the Eastern and Western Districts of Missouri.

- ^ Recess appointment; not confirmed by the Senate.

- ^ Received a second recess appointment and was again rejected by the Senate.

- ^ Received a third recess appointment; formally nominated on January 13, 1949, confirmed by the Senate on January 31, 1949, and received commission on February 2, 1949.

|

|

Chief judges

editChief judges have administrative responsibilities with respect to their district court. Unlike the Supreme Court, where one justice is specifically nominated to be chief, the office of chief judge rotates among the district court judges. To be chief, a judge must have been in active service on the court for at least one year, be under the age of 65, and have not previously served as chief judge.

A vacancy is filled by the judge highest in seniority among the group of qualified judges. The chief judge serves for a term of seven years, or until age 70, whichever occurs first. The age restrictions are waived if no members of the court would otherwise be qualified for the position.

When the office was created in 1948, the chief judge was the longest-serving judge who had not elected to retire, on what has since 1958 been known as senior status, or declined to serve as chief judge. After August 6, 1959, judges could not become or remain chief after turning 70 years old. The current rules have been in operation since October 1, 1982.

Succession of seats

edit

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

United States Attorneys

editList of U.S. Attorneys since 1857[34][35]

- Calvin F. Burns (1857–1861)

- Asa S. Jones (1861–1862)

- William W. Edwards (1862–1863)

- William N. Grover (1863)

- John Willock Noble (1867–1870)

- Chester H. Krum (1870–1876)

- William H. Bliss (1876–1887)

- Thomas P. Bashaw (1887–1889)

- George D. Reynolds (1889–1894)

- William H. Clopton (1894–1898)

- Edward A. Rozier (1898–1902)

- David Patterson Dyer (1902–1907)

- Henry W. Blodgett (1907–1910)

- Charles A. Houts (1910–1914)

- Arthur L. Oliver (1914–1919)

- Walter Lewis Hensley (1919–1920)

- James E. Carroll (1920–1923)

- Allen Curry (1923–1926)

- Louis H. Breuer (1926–1934)

- Harry C. Blanton (1934–1947)

- Drake Watson (1947–1951)

- George L. Robertson (1951–1953)

- William W. Crowdis (1953)

- Harry Richards (1953–1959)

- William H. Webster (1959–1961)

- D. Jeff Lance (1961–1962)

- Richard D. Fitzgibbon, Jr. (1962–1967)

- Veryl Riddle (1967–1969)

- James E. Reeves (1969)

- Daniel Bartlett, Jr. (1969)

- James E. Reeves (1969–1973)

- Donald J. Stohr (1973–1976)

- Barry A. Short (1976–1977)

- Robert D. Kingsland (1977–1981)

- Thomas E. Dittmeier (1981–1990)

- Stephen B. Higgins (1990–1993)

- Edward L. Dowd, Jr. (1993–1999)

- Michael W. Reap (1999–2000)

- Audrey G. Fleissig (2000–2001)

- Raymond Gruender (2001–2004)

- James Martin (2004–2005)

- Catherine Hanaway (2005–2009)

- Michael W. Reap (2009–2010)

- Richard G. Callahan (2010–2017)

- Caroline A. Costantin (2017)

- Jeffrey Jensen (2017–2020)

- Sayler A. Fleming (2020–present)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "U.S. District Courts of Missouri, Legislative history". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Meet the U.S. Attorney". December 31, 2020. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022.

- ^ "The U.S. District Courts and the Federal Judiciary". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Rush Hudson Limbaugh Sr. U.S. Courthouse". United States General Services Administration. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- ^ 3 Stat. 653

- ^ Dickens, Asbury (1852). A Synoptical Index to the Laws and Treaties of the United States of America. Boston: Little, Brown and company. p. 393.

- ^ 5 Stat. 176

- ^ 11 Stat. 197

- ^ a b c d e f g Broadhead, James O. (March 5, 1887). "Address of Col. J. O. Broadhead". In Bar Association of St. Louis (ed.). Proceedings of the Saint Louis Bar on the Retirement of Hon. Samuel Treat. St. Louis: Nixon-Jones printing co. pp. 10–17.

- ^ "Robert William Wells". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Samuel Treat". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. District Courts of Missouri, Authorized Meeting Places". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c Neely, Mark E. Jr. (January 3, 1991). The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. Oxford University Press. pp. 32. ISBN 978-0-7607-8864-6.

- ^ 14 Stat. 517

- ^ a b c Morris, Jeffrey Brandon (November 16, 2007). Establishing Justice in Middle America: A History of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (1st ed.). Univ Of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4816-0.

- ^ a b "St. Louis, Missouri, 1884". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Hannibal, Missouri, 1888". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Gray, Melvin L. (1901). "United States Courts". In Howard L. Conard (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Missouri. Southern History Co. pp. 267–269.

- ^ 42 Stat. 838

- ^ 49 Stat. 659

- ^ "St. Louis, 1935". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse". U.S. General Services Administration. April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Decker, Scott H.; et al. (February 2007). "Project Safe Neighborhoods: Strategic Interventions" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. p. 3. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Norman v. B & O Railroad, 294 U.S. 240 (1935)

- ^ Planned Parenthood of Missouri v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52 (1976).

- ^ Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988).

- ^ Beussink v. Woodland R-IV School district, 30 F. Supp. 2d 1175 (E.D. Mo. 1998).

- ^ Court transcript, accessed March 30, 2009. Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000).

- ^ Sell v. United States, 539 U.S. 166 (2003).

- ^ Brown Shoe Co., Inc. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294 (1962).

- ^ United Shoe Machinery Corp. v. United States, 258 U.S. 451 (1922).

- ^ Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co., 467 U.S. 986 (1984).

- ^ "Bicentennial Celebration" (PDF). www.justice.gov. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "The Political Graveyard: U.S. District Attorneys in Missouri".