The economics of terrorism is a branch of economics dedicated to the study of terrorism. It involves using the tools of economic analysis to analyse issues related to terrorism, such as the link between education, poverty and terrorism, the effect of macroeconomic conditions on the frequency and quality of terrorism, the economic costs of terrorism, and the economics of counter-terrorism.[1] The field also extends to the political economy of terrorism, which seeks to answer questions on the effect of terrorism on voter preferences and party politics.

Research has extensively examined the relationship between economics and terrorism, but both scholars and policy makers have often struggled to reach a consensus on the role that economics plays in causing terrorism, and how exactly economic considerations could prove useful in understanding and combatting terrorism.[2]

Introduction

editThe study of terrorism economics dates back to a 1978 study by William Landes, who conducted research into what acted as effective deterrents for airplane hijackings.[3] Looking at aircraft hijacking trends in the US between 1961 and 1976, Landes found that the reduction in the number of hijackings after 1972 was associated with the introduction of mandatory screening systems, the increased chance of apprehension and harsher criminal penalties.[4] He forecasted that if mandatory screening was not in place, and if the probability of apprehension remained equal to its 1972 value, there would have been between 41 and 67 additional hijacking between 1973 and 1976.[5]

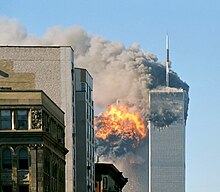

Since the attack on the World Trade Center, there have been many more empirical and theoretical contributions that have helped to expand the field. Notably, Alan Krueger and Jitka Maleckova published a paper in 2003 that demonstrated little relationship between poverty and terrorism, in contrast to the common wisdom following 9/11.[6]

Definition of terrorism

editScholars and politicians alike have struggled to agree on a universal definition of terrorism.[7] Terrorism expert Jessica Stern asserts that "the student of terrorism is confronted with hundreds of definitions in the literature."[8] However, over this period, scholars dedicated to the study of the economics of terrorism have converged to a standard definition that is frequently used for economic research.[9] It is based on the definition employed by the US State Department, and is primarily used because it uses concrete language, and avoids phrases that create ambiguity in classification, like "often" and "especially."

“The term ‘terrorism’ means premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience.”

— US Department of State (Title 22 of the US Code, Section 2656 (d))[10]

Poverty, education and terrorism

editPoverty as cause of terrorism

editFor many years, the common wisdom was that poverty and ignorance (i.e. lack of education) was the root cause of terrorist activity. This opinion was once held by politicians across both sides of the aisle in the United States and leading international officials, including George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Shimon Peres, James Wolfensohn, Elie Wiesel, and terrorism expert Jessica Stern.[11]

“We fight against poverty because hope is an answer to terror"

— George W. Bush, Former President of the United States (2002)[12]

"On one side stand the forces of terror and extremism, who cloak themselves in the rhetoric of religion and nationalism. These forces of reaction feed on disillusionment, poverty and despair"

— Bill Clinton, Former President of the United States (1994)[13]

"The dragon's teeth of terrorism are planted in the fertile soil of wrongs unrighted, of disputes left to fester for years or even decades, of failed states, of poverty and deprivation"

— Tony Blair, Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2001)[14]

"We have to address ourselves to the young generation and to education, so that neither poverty nor ignorance will continue to feed fundamentalism"

— Shimon Peres, Former Prime Minister of Israel (1993)[15]

"The war on terrorism will not be won until we have come to grips with the problem of poverty and thus the sources of discontent"

— James Wolfensohn, Former President of the World Bank (2001)[16]

"Education is the way to eliminate terrorism"

— Elie Wiesel, 1986 Nobel Peace Prize Recipient (2001)[17]

"We have a stake in the welfare of other peoples and need to devote a much higher priority to health, education, and economic development, or new Osamas will continue to arise"

— Jessica Stern, Lecturer at Harvard University and Author of "The Ultimate Terrorists" (2001)[18]

Origins of poverty theory

editAlan Krueger has argued that the origins of this common wisdom are an inaccurate early empirical study by Arthur Raper.[19] Using early empirical analysis, Raper researched the link between the number of lynchings in the south of the United States and the price of cotton, which he used as a proxy for economic conditions. He found a strong negative correlation between the price of cotton and the number of lynchings, and concluded that as economic conditions improve, people commit fewer hate crimes. In 1940, Yale psychologists Carl Holland and Robert Sears cited Raper in a crime economics paper that argued people are more likely to commit violence against others when they are poor.[20] Krueger has alleged that these studies were the beginning of the literature on hate crimes, and the origin of the common wisdom that there is a positive correlation between poverty and terrorism.[19]

However, subsequent research has rejected Raper's findings. In 2001, Green, McFalls and Smith published a paper that debunked Raper's conclusion regarding the relationship between economic conditions and hate crimes.[21] By extending Raper's data-set beyond 1929 and running a multiple regression with controls, they found that Raper had merely identified a correlation between the two variables in the time period of his analysis, and that there was actually no meaningful relationship at all between the price of cotton and the number of lynchings.[21]

Other studies have also refuted the link between economic conditions and hate crimes. In 1998, Green, Glaser and Rich published a study on the relationship between citywide unemployment and homophobic, racist, and anti-semitic hate-crimes, and found no significant correlation.[22] Swarthmore economists Fred Pryor and Philip Jefferson found similar results in their study on the link between the existence of hate groups and both local unemployment rates and the disparity in earnings between blacks and whites. In accordance with the surrounding literature on the topic, they found no correlation with either.[23]

Advanced empirical analysis

editAfter noticing that the terrorists involved in 9/11 were well-educated and wealthy,[24] and noting a lack of evidence for the common claims regarding the relationship between economic conditions and terrorism, many economists decided to conduct research on the economics of terrorism.

In 2003, Alan Krueger published a seminal paper that debunked the common wisdom that terrorists are uneducated and poor.[25] By looking at a data-set of Hezbollah militants who died in action from 1982 to 1994 and a fair comparison group from the Lebanese population, he found that Hezbollah militants were better educated than their peers in the population, and less likely to come from poverty.[25] In the same paper, Krueger cited Claude Berrebi's analysis of Hamas, PIJ and PNA terrorist attacks in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories between 1987 and 2002. Berrebi, in accordance with Krueger's own research, found that Palestinian terrorists and even suicide bombers were both more likely to have attended college than the average Palestinian, and less likely to come from a poverty stricken background.[25] In fact, 2 of the suicide bombers in Berrebi's data-set were actually the sons of millionaires.[26] From his own and Berrebi's analysis, Krueger concluded that there is little reason to the argument that a reduction in poverty or increase in educational attainment would meaningfully reduce international terrorism.

In 2007, Claude Berrebi published a paper looking at the link between education and terrorism among Palestinian suicide bombers, which used an updated data-set that included failed and foiled attacks between 2000 and 2006. His conclusions reaffirmed Krueger's findings: both higher education and a higher standard of living were found to be positively associated with participation in Hamas or PIJ and with becoming a suicide bomber, whilst being married reduced the probability of involvement in terrorist activities. Berrebi also did much to develop the profile of a terrorist from Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, finding that at least 96% of terrorists in his data-set had at least a high-school education, and that 93% were under the age of 34.[26]

Krueger also investigated the theory that, whilst terrorists may be better educated and wealthier than the population, poor macroeconomic conditions for the country as a whole might drive wealthier citizens to commit acts of terrorism. Contrary to this theory, he found that when one accounts for the fact that poorer countries are less likely to have basic civil liberties, there is no difference between the number of terrorists springing from the poorest or the richest countries.[25]

Although studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between income, education and the propensity to be a terrorist, scholars are divided on whether this means that these factors cause someone to engage in terrorist activity. In 2005, Ethan Bueno de Mesquita developed a theoretical model in which he argued that terrorist organisations would choose the most well-educated and experienced volunteers since they would be the most effective terrorists.[27] This theory was supported by a 2007 study, in which Berrebi found that terrorists who are older, wealthier, and better educated are more likely to produce a successful, and deadlier, terrorist attack.[28] Whether the positive relationship between terrorism and income/education is a result of the demand-side of terrorism is uncertain, however, the rise of lone wolf attacks might give way to an opportunity for terrorism research in which the sample of terrorists will not have been filtered by terrorist organisations first.

Macroeconomic conditions and the frequency of terrorism

editAlongside the array of literature that examines the link between individual poverty and the propensity to become a terrorist, there is also research dedicated to the effect of macroeconomic conditions on the occurrence of terrorism. A paper published by Bloomberg, Hess and Weerapana in 2004 examined exactly this using a panel data set of 127 countries from 1968-1991. They concluded that for democratic and high income countries, economic contractions increase the probability of terrorist activity.[29]

However, this study has been critiqued for not separating the terrorist venue country from the terrorist target country in its analysis. In a working paper from 2003, Claude Berrebi addressed this, noting that terrorist attacks would be more likely to be caused by the economic conditions where the perpetrators come from, than where the attack actually takes place. Taking this into account, he found that there was no sustainable link between economic conditions in Gaza and the West Bank, and the frequency of terrorism produced by terrorists from these regions.[30] These findings were supported by Alberto Abadie, who also failed to find a significant association between terrorism and macroeconomic variables once control variables were accounted for. Abadie argued that political freedom has a far stronger, and monotonic, relationship with terrorism, with terrorism peaking in countries that transition from authoritarian to democratic governments.[31] In accordance with these findings, UNC political scientist James Piazza found no significant relationship between poverty, malnutrition, inequality, unemployment, inflation or economic growth and terrorism, but found that ethno-religious diversity, increased state repression, and a large number of political parties are good predictors of terrorist activity. He concluded that this might be a result of the social cleavage theory, which argues that terrorism is a result of deep social divisions in the electorate rather than socio-economic factors.[32]

Alan Krueger and David Laitin developed the discussion surrounding the link between macroeconomic variables and terrorism in a 2008 paper that explicitly examined whether economics could explain either terrorists' national origins, or why some countries are targets of terrorism. They found that, controlling for political regime, the national economy is not a good predictor of terrorist origins, but countries that are terrorism targets are those which are economically successful.[33]

Whilst the linear relationship between macroeconomic conditions and terrorism has been questioned, recent research has provided evidence that a nonlinear relationship does exist. A paper published in 2016 by Enders, Hoover, and Sandler looked at the relationship between real GDP and terrorism, and developed a terrorism Lorenz curve. They found that the peak terrorism level differed for domestic and transnational terrorism, which they suggested was a result of domestic terrorism being motivated by economic grievances and transnational terrorism being motivated by foreign policy grievances. Consequently, they found that the peak level of domestic terrorism corresponds to a lower real GDP per capita than transnational terrorism. In addition to separating domestic and transnational terrorism in their analysis, they also separated their analysis between two time periods - pre-1993 and post-1993 - to reflect the fact that the nature of terrorism changed in the latter period due to the rise of religious fundamentalism in the Middle East. By doing this, they discovered that before 1993 there was a greater concentration of transnational terrorist attacks from terrorists who come from countries with a higher GDP/capita. Since then the composition of terrorist groups has shifted from leftists to religious fundamentalists, and the link between macroeconomic conditions and terrorism is likely to have changed. Their article offers an explanation for the diverse findings in the literature, which they find to be the assumed linear specification, aggregation of terrorist attacks, and different time periods used, which provide too many confounding and opposing influences.[34]

Macroeconomic conditions and the quality of terrorism

editPolitical scientist Ethan Bueno de Mesquita has presented a model of terrorism that proposes that the reason why terrorists are normally better educated than the general population is that terrorist organizations screen volunteers for quality. In periods of recession and low economic opportunity, the supply of potential terrorists will increase, and terrorist groups will have a larger pool of highly qualified potential terrorists to choose from. Hence, in these periods of poor economic opportunity, the quality of terrorists will increase, and thus economic recession will be positively correlated with the quality/threat of terrorism rather than the frequency of terrorism.[27]

"Our biggest problem is the hordes of young men who beat on our doors, clamouring to be sent. It is difficult to select only a few. Those whom we turn away return again and again, pestering us, pleading to be accepted"

— Senior member of Hamas as reported by Hassan (2001)

This theory was put to the test in a paper published in 2012 by Berrebi, Benmelech and Klor, which looked at the relationship between economic conditions and the quality of suicide terrorism. They found that although poor economic conditions do not correlate with the frequency of terror, they do correlate with the quality of terror. High unemployment rates allow terror groups to recruit better educated, older, and more experienced suicide terrorists, who are in turn more effective killers, thus increasing the threat of terrorism. Consequently, they support policies to improve economic development since these might reduce the lethality of terrorism. However, they emphasise the importance of paying attention to the ideology of local organisations that aid is administered to, since aid can be used to indirectly increase the frequency of terrorist attacks.[35]

Timing and location of terrorism

editA paper published in 2007 by Claude Berrebi and Darius Lakdawalla examined how the risk of terrorism in Israel changes over time. Using a database of Israeli terrorist attacks from 1949 to 2004, they found that long periods of time without an attack signal lower risk of another attack for most areas, but higher risk of another attack in important areas, such as capitals and contested sites (e.g. Jerusalem). In the same paper, they also found that when it comes to selecting targets, terrorists act as rational agents: they are more likely to attack targets that are accessible from their base and international borders, that are symbolic or governmental, or that are in more Jewish areas.[36]

A panel data study by Konstantinos Drakos and Andreas Gofas also looked at the profile of a terrorist attack venue (i.e. targets), but for transnational terrorist activity rather than Palestinian terrorist activity. They found that the average terrorist attack venue is characterised by low economic openness, high demographic stress, and high participation in international disputes. They found no strong statistical relationship between the level of democracy and terrorist activity, although theorised that the level of democracy affects how accurately terrorist activity is reported.[37]

Economic consequences of terrorism

editMacroeconomic consequences of terrorism

editThere are two competing views on the impact of terrorism on modern economies. Some scholars have argued that terrorist attacks have a small impact on the economy since they have a negligible impact on physical and human capital (i.e., buildings can be rebuilt, casualties are never that large).[38] The literature supports this theoretical outlook on the economic impacts of natural disasters, which has found that natural disasters in modern economies do not often have serious long-term economic effects.[19] Other scholars have argued that terrorism can have a big impact on the economy, since if an important area of the economy is hit (e.g., financial sector), the whole economy could face repercussions. There is a wealth of theoretical and empirical work on the effect of terrorism on macroeconomic outcomes.[19]

Theoretically, terrorism endangers life, leading to a reduction in the value of the future relative to the present. Therefore, an increase in terrorism should decrease investment and long run income and consumption. Governments could try and offset the impact of terrorism by spending on security, although it would not be optimal for a government to spend so much as to fully offset the impact of terrorism. Therefore, even an optimizing government could not totally nullify the negative impacts of terrorism on the economy.[39]

Bloomberg, Hess and Orphanages have found empirically that the occurrence of terrorism has a significant negative effect on economic growth, albeit a smaller and less persistent effect than war or civil conflict. Furthermore, they found that terrorism is associated with a reduction in investment spending and an increase in government spending. They also noted that although terrorist attacks are more frequently found in OECD countries, the negative effect of terrorist attacks on these economies is smaller.[40] In accordance with this study, Abadie and Gardeazabal found whilst analyzing terrorism in the Basque Country that the outbreak of terrorism corresponded with a significant decline in GDP per capita in comparison to other similar regions. During the truce negotiations between 1998 and 1999, they found that stocks of firms that operate in the Basque Country improved in performance when the truce became credible, and suffered at the end of the cease-fire.[41] In a later 2008 paper, the same researchers found that terrorism reduces the expected return to investment, and consequently lowers net foreign direct investment. They found the magnitude of this effect to be large.[42]

Terrorism and expectations

editThe behavioral inattention theory suggests that behavioral dynamics are related to the agent's attention.[43] Terrorism changes people's attention and thus modifies their rational behaviors into more behavioral ones. Microeconomic data related to investment in human capital (education) in Kenya during terrorism support this evidence.[44] Terrorism also changes expert and market forecast performances of inflation and exchange rate, even after controlling for uncertainty or volatility. Exchange rate forecasts are significantly impacted by fatalities caused by terrorism due to their more international effect.[45]

Terrorism and tourism

editThe terrorism effects on tourism arrivals show substitution and generalization effects and confirm the existence of a consumer's short memory effect.[46] Spillover effects of terrorism on market shares and tourism display significant contagion effects of terrorism on market shares, as is evidence of the effect of terrorism on the substitutability between countries.[47]

Terrorism and the Israeli economy

editIsrael is a country that has suffered largely from terrorism, and hence provides a good case-study for the impact of terrorism on an economy. A study by Zvi Eckstein and Daniel Tsiddon found that continued terror at the level that Israel experienced in 2003 decreases annual consumption per capita by around 5%. They concluded that if Israel had not suffered from terrorist attacks in the 3 years prior to 2003, their output per capita would have been 10% higher in 2003.[48]

Terrorism has also been found to reduce investment in Israel. David Fielding found that there is a strong relationship between the number of people killed in Intifada-related terror attacks and aggregate investment. Violence of all kind reduces investment demand, suggesting that aggressive security measures are less effective than the pursuit of a peace agreement, which would remove the incentive for violent political conflict. Lasting peace would substantially increase investment, Fielding argues.[49]

Berrebi, Benmelech and Klor found similar evidence regarding the consequences of terrorism for the Palestinian (i.e. harbouring) in their 2010 paper. They found evidence that a successful suicide terrorist attack leads to 5.3% increase in a district's unemployment, leads to a more than 20% increase in the likelihood that a district's average wages fall in the following quarter, and reduces the number of Palestinians working in Israel from that district. Significantly, they found that these effects are persistent, lasting for at least 6 months after a suicide attack. These results demonstrate that terrorist attacks in Israel harm the Palestinian in addition to the direct damages to the targeted Israeli economy.[50]

Terrorism and individual choice

editBecker and Rubinstein have theorised that the impact of fear induced by terrorism will vary depending on individuals' capacity to manage their emotions, which is often influenced by economic incentives. By researching the response of Israelis to terrorist attacks during the Second Intifada, they found that the impact of terrorism on the usage of goods and services subject to terror (e.g. buses, coffee shops, clubs) reflects only the reactions of sporadic users. They found no impact of terrorist attacks on demand for these goods and services by frequent users, but a significant impact on casual users. They also noted that suicide attacks that occur during regular media coverage days have a bigger impact than those that occur before a holiday or a weekend, especially amongst less educated families.[51]

Terrorism and the labor force

editA panel data study has shown that terrorist attacks decrease female labor force participation and increase the gap between male and female labor force participation in a statistically significant way. The greatest effects were found from transnational attacks, and those against government entities.[52]

Terrorism and fertility

editA panel data study has shown that terrorist attacks decrease fertility, reducing both the expected number of children a woman has over her lifetime, and increasing the probability of miscarriage.[53]

Terrorism and philanthropy

editTheoretically, net philanthropic responses to terrorism can vary. Some individuals react to terrorism by reducing their charitable activities, whilst others express more generosity by increasing how much they give, either out of empathy with the victims, or out of a heightened sense of patriotism. A paper published in 2016 by Claude Berrebi and Hanan Yonah found that terror attacks considerably increase the amount that individuals and households give to charity, suggesting that the latter response outweighs the former. Higher income individuals donate more, but terrorism reduces their relative generosity, and women and non-married donors appear to reduce their average donations in response to terrorism. It's suggested that those who reduce their donations following terrorist attacks are more sensitive to terrorist-related economic risks.[54]

Terrorism and Electoral Outcomes

editBerrebi and Klor have provided theory about the interaction between terrorism and electoral outcomes. They contend that support for the country's right-wing parties is likely to increase after periods with high levels of terrorism, and decrease after periods without it. They also contend that the expected level of terrorism is higher when a left-wing party is in government than when a right-wing party is in office. In a 2006 paper they tested these theories, and found that the first is strongly supported by public opinion poll data from the Israeli electorate, whilst the second is strongly supported by the terrorism trends under the three Israeli governments between 1990 and 2003.[55]

In 2008, the same set of researchers developed the literature on the relationship between terrorism and electoral outcomes by analysing the causal effects of terrorism on Israeli political opinion. They found that the occurrence of a terror attack in a province within three months of an election leads to an 1.35% increase in that province's support for the right-of-centre political parties. This is politically significant in the case of Israel due to the high level of terrorism in the country. Berrebi and Klor also found that a death as a consequence of terrorism can have an impact on electoral outcomes beyond where the attack actually took place, with its impact being stronger if it occurs close to an election. In left-leaning provinces, local terror fatalities increase support for right-of-centre political parties, whilst terror fatalities outside of the province increase support for left-of-centre political parties. They conclude that their analysis provides evidence for the theory that the electorate is sensitive to terrorism, and demonstrates that terrorism polarises the electorate.[56]

Economics of counter-terrorism

editTerrorism economics is studied in order to mitigate or reduce the threat of terrorism. As such, some of the most applicable literature for public policy purposes comes from research surrounding the economics of counter-terrorism. Walter Enders and Todd Sandler published a paper in 1993 that evaluated the effectiveness of policies designed to thwart terrorism. They found that the installation of metal detectors in airports reduced the number of airplane highjackings, but increased the number of other attacks (e.g. kidnappings and assassinations). Similarly, the fortification of US embassies in 1976 reduced the number of embassy attacks but increased the number of assassinations. From this they concluded that anti-terrorism policies under Ronald Reagan did not lead to any long-term reduction in the threat of terrorism against the United States. They argue that the government should always consider the indirect effects of implementing a policy designed to reduce terror.[57]

The effectiveness of assassinating members of terrorist organisations in order to curb terrorism was researched by Asaf and Noam Zussmann in 2006. They theorised that the net effect of assassination on future terrorism would depend on the relative size of two opposing effects: the damage that the assassination of a terrorist does to their organisation's capabilities, and the increased motivation for a future attack in response. Under the assumption that terrorism would negatively impact the Israeli economy, they used the Israeli stock market as an indicator for the effectiveness of a counter-terrorism assassination. They found that the market improved following assassinations of senior military leaders of terrorist organisations and declined following assassinations of senior political figures in terrorist organisations. Consequently, they argue that the assassination of the former is effective, but the assassination of the latter is counterproductive. They also found that the assassination of low ranking terrorists did not significantly impact the stock market.[58]

Berrebi, Benmelech and Klor examined the effectiveness of house demolitions as a counterterrorism tactic in a paper published in 2015. They found that punitive house demolitions targeted at Palestinian suicide terrorists result in an immediate and significant decrease in the number of suicide attacks. In contrast, the implementation of curfews and precautionary house demolitions based upon the location of the house result in a significant increase in the number of suicide attacks. They concluded that selective violence can be an effective counterterrorism tool, but indiscriminate violence is not.[59]

References

edit- ^ Enders, Walter (2016). The Economics of Terrorism. Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-78471-186-3.

- ^ "CIAO Case Study: Economics of Terrorism". ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ Sandler, Todd (April 2013). "Advances in the Study of the Economics of Terrorism". Southern Economic Journal. 79 (4): 768–773. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-2013.007.

- ^ a b Landes, William (April 1978). "An Economic Study of U.S. Aircraft Hijacking, 1960-1976" (PDF). Journal of Law and Economics. 21: 1–31. doi:10.1086/466909. S2CID 159359142.

- ^ Enders, Walter; Sandler, Todd (1993). "The Effectiveness of Antiterrorism Policies: A Vector-Autoregression-Intervention Analysis". American Political Science Review. 87 (4): 829–844. doi:10.2307/2938817. JSTOR 2938817. S2CID 144629520.

- ^ Krueger, Alan; Maleckova, Jitka (2003). "Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17 (4): 119–144. doi:10.1257/089533003772034925. S2CID 14243744.

- ^ Williamson, Myra (2016-04-01). Terrorism, War and International Law: The Legality of the Use of Force Against Afghanistan in 2001. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-04594-6.

- ^ Stern, Jessica (2009-10-13). Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants Kill. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-175539-2.

- ^ Sandler, Todd (2013). "Advances in the Study of the Economics of Terrorism". Southern Economic Journal. 79 (4): 768–773. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-2013.007.

- ^ Schmid, Alex (2013). The Routledge handbook of terrorism research. Routledge. ISBN 9780415520997.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude (2007). "Evidence about the Link Between Education, Poverty and Terrorism among Palestinians". Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy. 13 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2202/1554-8597.1101. S2CID 201102083.

- ^ "Statement by United States of America at the International Conference on Financing for Development; Monterrey, Mexico; 22 March 2002". Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ "GLORIA Center".

- ^ "Full text of Tony Blair's speech at the Lord Mayor's banquet". Archived from the original on 2003-08-20. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ "Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Archived from the original on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ "World Bank's war on poverty". 2002-03-06.

- ^ "Getting at the roots of terrorism". Christian Science Monitor. 2001-12-10.

- ^ "ISP - Publication - Being Feared is Not Enough to Keep Us Safe". Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ a b c d KRUEGER, ALAN B. (2007). What Makes a Terrorist: Economics and the Roots of Terrorism (New ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13875-6. JSTOR j.ctt7t153.

- ^ Hovland, Carl; Sears, Robert (1940). "Minor Studies of Aggression: VI. Correlation of Lynchings with Economic Indices". The Journal of Psychology. 9 (2): 301–310. doi:10.1080/00223980.1940.9917696.

- ^ a b Green, Donald; McFalls, Laurence; Smith, Jennifer (2001). "Hate Crime: An Emergent Research Agenda". Annual Review of Sociology. 27: 479–504. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.479.

- ^ Green, Donald; Glaser, Jack; Rich, Andrew (1998). "From Lynching to Gay Bashing: The Elusive Connection Between Economic Conditions and Hate Crime". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (1): 82–92. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.82. PMID 9686451.

- ^ Pryor, Fred; Jefferson, Philip (1999). "On The Geography of Hate". Economics Letters. 65 (3): 389–395. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(99)00164-0.

- ^ Acheson, Ian (30 January 2018). "Uncomfortable truths about what makes a terrorist". CapX. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Krueger, Alan; Maleckova, Jitka (2003). "Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17.

- ^ a b Berrebi, Claude (February 2007). "Evidence about the Link Between Education, Poverty and Terrorism among Palestinians". Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy. 13 (1). doi:10.2139/ssrn.487467. S2CID 26872121.

- ^ a b de Mesquita, Ethan Bueno (July 2005). "The Quality of Terror". American Journal of Political Science. 49 (3): 515–530. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00139.x.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Benmelech, Efraim (2007). "Human Capital and theProductivity of Suicide Bombers". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 21 (3): 223–238. doi:10.1257/jep.21.3.223.

- ^ S.Brock Blomberg, Gregory Hess, Akila Weerapana, Economic conditions and terrorism, European Journal of Political Economy, Volume 20, Issue 2, June 2004, Pages 463-478

- ^ Berrebi, Claude (2003). "Evidence About The Link Between Education, Poverty and Terrorism Among Palestinians (Working Paper)". Princeton University.

- ^ Abadie, Alberto (May 2006). "Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism" (PDF). American Economic Review. 96 (2): 50–56. doi:10.1257/000282806777211847.

- ^ Piazza, James (2006). "Rooted in Poverty?: Terrorism, Poor Economic Development, and Social Cleavages". Terrorism and Political Violence. 18: 159–177. doi:10.1080/095465590944578. S2CID 54195092.

- ^ Krueger, Alan B.; Laitin, David D. (2008). "Kto Kogo?: A Cross-Country Study of the Origins and Targets of Terrorism". Terrorism, Economic Development, and Political Openness. pp. 148–173. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511754388.006. ISBN 9780511754388. S2CID 1398700.

- ^ Enders, Walter; Hoover, Gary; Sandler, Todd (March 2016). "The Changing Nonlinear Relationship between Income and Terrorism". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (2): 195–225. doi:10.1177/0022002714535252. PMC 5418944. PMID 28579636.

- ^ Benmelech, Efraim; Berrebi, Claude; Klor, Esteban (January 2012). "Economic Conditions and the Quality of Suicide Terrorism". The Journal of Politics. 74 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1017/S0022381611001101. S2CID 39511007.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Lakdawalla, Darius (April 2007). "How Does Terrorism Risk Vary Across Space and Time? An Analysis Based On the Israeli Experience". Defence and Peace Economics. 18 (2): 113–131. doi:10.1080/10242690600863935. S2CID 218522974.

- ^ Drakos, Konstantinos; Gofas, Andreas (April 2006). "In Search of the Average Transnational Terrorist Attack Venue". Defence and Peace Economics. 17 (2): 73–93. doi:10.1080/10242690500445387. S2CID 154890997.

- ^ Becker, G; Murphy, K (29 October 2001). "Prosperity will rise out of the ashes". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Eckstein, Zvi; Tsiddon, Daniel (2004). "Macroeconomic consequences of terror: theory and the case of Israel". Journal of Monetary Economics. 51 (5): 971–1002. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.05.001. S2CID 18657170.

- ^ Blomberg, Brock; Hess, Gregory; Orphanides, Athanasios (2004). "The macroeconomic consequences of terrorism" (PDF). Journal of Monetary Economics. 51 (5): 1007–1032. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.04.001. S2CID 153863696.

- ^ Abadie, Alberto; Gardeazabal, Javier (March 2003). "The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country". The American Economic Review. 113–132.

- ^ Abadie, Alberto; Gardeazabal, Javier (2008). "Terrorism and the world economy". European Economic Review. 52: 1–27. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.08.005. hdl:10810/6734. S2CID 14081690.

- ^ Gabaix, Xavier (January 1, 2019). "Chapter 4 - Behavioral inattention". In Bernheim, B. Douglas; DellaVigna, Stefano; Laibson, David (eds.). Handbook of Behavioral Economics - Foundations and Applications 2. Vol. 2. Book Publishers. pp. 261–343. doi:10.1016/bs.hesbe.2018.11.001. ISBN 9780444633750. ISSN 2352-2399.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Alfano, Marco; Gorlach, Joseph-Simon (March 2019). "Terrorism, education and the role of expectations: evidence from al-Shabaab attacks in Kenya". Working Papers (1904). University of Strathclyde Business School, Department of Economics. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ Benchimol, Jonathan; El-Shagi, Makram (2020). "Forecast Performance in Times of Terrorism" (PDF). Economic Modelling. 91 (September): 386–402. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2020.05.018. S2CID 226193466.

- ^ Seabra, Claudia; Reis, Pedro; Abrantes, José Luís (2020). "The influence of terrorism in tourism arrivals: A longitudinal approach in a Mediterranean country". Annals of Tourism Research. 80 (January): 102811. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2019.102811. PMC 7148868. PMID 32572289.

- ^ Drakos, Konstantinos; Kutan, Ali M. (2003). "Regional Effects of Terrorism on Tourism in Three Mediterranean Countries". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 47 (5): 621–641. doi:10.1177/0022002703258198. JSTOR 3176222. S2CID 153835114.

- ^ Eckstein, Zvi; Tsiddon, Daniel Macroeconomic consequences of terror: theory and the case of Israel (2004). "Macroeconomic consequences of terror: theory and the case of Israel". Journal of Monetary Economics. 51 (5): 971–1002. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.05.001. S2CID 18657170.

- ^ Fielding, David (February 2003). "Modelling Political Instability and Economic Performance: Israeli Investment during the Intifada". Economica. 70 (277): 159–186. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.t01-2-00276. S2CID 155040448.

- ^ Benmelech, Efraim; Berrebi, Claude; Klor, Esteban (2010). "The Economic Cost of Harboring Terrorism". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 54 (2): 331–353. doi:10.1177/0022002709355922. S2CID 17513911.

- ^ Becker, Gary; Rubinstein, Yona (February 2011). "Fear and the Response to Terrorism: An Economic Analysis".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Berrebi, Claude; Ostwald, Jordan (November 2014). "Terrorism and the Labor Force: Evidence of an Effect on Female Labor Force Participation and the Labor Gender Gap". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (1): 32–60. doi:10.1177/0022002714535251. S2CID 158942916.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Ostwald, Jordan (January 2015). "Terrorism and fertility: evidence for a causal influence of terrorism on fertility". Oxford Economic Papers. 67 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1093/oep/gpu042. S2CID 55595741.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude (December 2016). "Terrorism and philanthropy: the effect of terror attacks on the scope of giving by individuals and households". Public Choice. 169 (3–4): 171–194. doi:10.1007/s11127-016-0375-y. S2CID 151772819.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Klor, Esteban (December 2006). "On Terrorism and Electoral Outcomes". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 50 (6): 899–925. doi:10.1177/0022002706293673. S2CID 3559040.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Klor, Esteban (August 2008). "Are Voters Sensitive to Terrorism? Direct Evidence from the Israeli Electorate" (PDF). American Political Science Review. 102 (3): 279–301. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080246. S2CID 229169955.

- ^ Enders, Walter; Sandler, Todd (December 1993). "The Effectiveness of Antiterrorism Policies: A Vector-Autoregression-Intervention Analysis". American Political Science Review. 87 (4): 829–844. doi:10.2307/2938817. JSTOR 2938817. S2CID 144629520.

- ^ Zussmann, Asaf; Zussmann, Noam (Spring 2006). "Assassinations: Evaluating the Effectiveness of an Israeli Counterterrorism Policy Using Stock Market Data". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 20 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1257/jep.20.2.193.

- ^ Berrebi, Claude; Benmelech, Efraim; Klor, Esteban (2015). "Counter-Suicide-Terrorism: Evidence from House Demolitions". The Journal of Politics. 77 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1086/678765. S2CID 222428459.