Edward Rudolph Bradley Jr. (June 22, 1941 – November 9, 2006) was an American broadcast journalist and news anchor who is best known for reporting with 60 Minutes and CBS News.

Ed Bradley | |

|---|---|

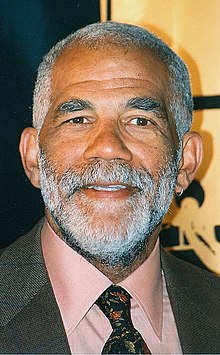

Bradley in 2001 | |

| Born | Edward Rudolph Bradley Jr. June 22, 1941 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 9, 2006 (aged 65) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | Cheyney State College (BS) |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Years active | 1964–2006 |

| Employer | CBS News |

| Television |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Awards | () |

After graduating from Cheyney State College, Bradley became a teacher and part-time radio disc jockey and reporter in Philadelphia, where his first major story was covering the 1964 Philadelphia race riot. He moved to New York City in 1967 and worked for WCBS as a radio news reporter. Four years later, Bradley moved to Paris, France, where he covered the Paris Peace Accords as a stringer for CBS News. In 1972, he transferred to Vietnam and covered the Vietnam War and the Cambodian Civil War, coverage for which he won Alfred I. duPont and George Polk awards. Bradley moved to Washington, D.C. following the wars and covered Jimmy Carter's first presidential campaign. He became CBS News' first African American White House correspondent, holding the position from 1976 to 1978. During this time, Bradley also anchored the Sunday night broadcast of the CBS Evening News, a position he held until 1981.

In 1981, Bradley joined 60 Minutes. While working for CBS News and 60 Minutes, he reported on approximately 500 stories and won numerous Peabody and Emmy awards for his work. He covered a wide range of topics, including the rescue of Vietnamese refugees, segregation in the United States, the AIDS epidemic in Africa, and sexual abuse within the Catholic Church. Bradley died in 2006 of leukemia.

Early life and education

editEdward Rudolph Bradley Jr. was born on June 22, 1941, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.[1] His parents divorced when he was young and he was raised in a poor household by his mother, Gladys Gaston Bradley, and spent summers with his father, Edward Sr., in Detroit.[2][3] Bradley attended high school at Mount Saint Charles Academy in Rhode Island and Saint Thomas More Catholic Boys School in Philadelphia, graduating from the latter in 1959.[4][5] He received a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Cheyney State College in 1964. While at Cheyney State, Bradley played offensive tackle for the school's football team.[6][7]

Career

edit1964–1971: Early career

editBradley began his career as a math teacher in Philadelphia in 1964. While working as a teacher, he also worked at WDAS as a disc jockey.[6][8] While working for WDAS, Bradley covered the 1964 Philadelphia race riot and interviewed Martin Luther King Jr. Those experiences led him to pursue a career as a journalist, with Bradley later saying, "I knew that God put me on this Earth to be on the radio."[6][9][10] Bradley moved to New York City in 1967, working for WCBS. While there, Bradley found he was primarily assigned stories most relevant to African American listeners. After confronting his editor about those assignments, Bradley received assignments on a broader array of topics. Bradley left WCBS in 1971.[11]

1971–1981: Vietnam, White House and CBS Evening News

editBradley moved to Paris, France, in 1971. He was fluent in French, and while there was hired by CBS News as a stringer.[2] He transferred to Saigon in 1972 to report on the Vietnam War and Cambodian Civil War, as well as reporting on the Paris Peace Accords.[12][13] While in Cambodia, Bradley was wounded by a mortar round. He transferred to CBS's Washington bureau in 1974, returning to Asia the following year to continue reporting on both wars. Bradley was one of the last American journalists to be evacuated in 1975 during the Fall of Saigon.[3][14] He was awarded Alfred I. duPont and George Polk awards for his coverage in Vietnam and Cambodia.[6]

In 1976, Bradley was assigned to cover Jimmy Carter's presidential campaign, as well as the Republican and Democratic national conventions, covering them until 1996.[15] Following Carter's victory, Bradley became CBS's first African American White House correspondent, a position he held from 1976 to 1978.[16] Bradley disliked the position as it tied him to the movements of the president.[3] Also in 1976, Bradley began anchoring the Sunday night broadcasts of the CBS Evening News, holding the post until 1981.[17] In 1978, he became one of the principal correspondents for the documentary program CBS Reports, also leaving in 1981.[18]

Bradley won the first of 20 News and Documentary Emmy Awards in his career for his 1979 documentary "The Boat People", reporting on Vietnamese refugees escaping the country via boat or ship, at one point wading into the water to assist in the rescue of the refugees.[1] "The Boat People" also earned Bradley an Edward Murrow Award, a duPont citation, and a commendation from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. The same year, another Bradley documentary, "Blacks in America: With All Deliberate Speed?", aired. The documentary detailed segregation in the United States and how the treatment of African Americans in the U.S. had changed since Brown v. Board of Education. The two-hour program also won duPont and Emmy awards.[6]

1981–2006: 60 Minutes

editFollowing Dan Rather's move to the CBS Evening News, Bradley joined the news magazine program 60 Minutes. According to producer Don Hewitt, Bradley's "calm, cool, and collected" reporting style was the right fit for the program.[1] His interview style has drawn comparisons to television detective Columbo and been described as "disarming", "confident", and "streetwise". He was noted for his ability to get interview subjects to divulge information on camera with his body language.[19][20] In his first decade on 60 Minutes, Bradley reported numerous high-profile stories in the 1980s on a variety of topics, including with Lena Horne, convicted criminal and author Jack Henry Abbott, and on schizophrenia. He won Emmys for all three stories.[15]

In 1986, Bradley interviewed singer Liza Minnelli and expressed interest in wearing an earring. Minnelli gave him a diamond stud after the interview, which Bradley began wearing on air. He was the first male reporter to consistently wear an earring on air, "challenging the notions of journalistic propriety", according to Robb Report writer Kristopher Fraser.[21][22] He became known for bucking fashion trends for newscasters. His iconic style included an array of patterns, a short beard, and the earring worn in his left ear.[22][10] Mike Wallace said after Bradley's death that he thought Bradley's decision to wear an earring inspired others to do the same.[23]

Bradley repeatedly turned down offers to anchor the CBS Evening News in the late 1980s, preferring instead to continue working on 60 Minutes.[24] His reporting in the 1990s included such topics as Chinese forced labor camps, Russian military installations, and the effects of nuclear weapons testing near Semey, Kazakhstan. He also profiled numerous people, including Thomas Quasthoff, Muhammad Ali, and Mike Tyson.[9][19] He won a series of awards for his reporting that decade, including Emmys, duPont citations, and a Peabody Award.[15] Bradley also anchored CBS's Street Stories from 1992 to 1993.[24] In 1995, he was awarded the grand prize Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for the CBS Reports documentary "In the Killing Fields of America".[18]

Throughout the 2000s until his death in 2006, Bradley continued to cover a variety of topics, including the AIDS epidemic in Africa, sexual abuse within the Catholic Church, and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till.[1][7] He also interviewed high-profile people, such as Bob Dylan and Neil Armstrong, and conducted the only television interview with Timothy McVeigh.[25][26] Bradley reported approximately 500 stories for 60 Minutes over his 25-year tenure with the program, more than any other correspondent over the same time period.[16][24] In 2005, Bradley was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the National Association of Black Journalists.[27]

Bradley's reporting was not without criticism. Washington Post columnist Brock Yates questioned the completeness of Bradley's 1986 report on acceleration systems failures with the Audi 5000 sedan and why Audi engineers reportedly could not reproduce the problem.[28] In 1989, Bradley reported on daminozide, a chemical used on apples, as well as seven pesticides used on the fruit. His report called daminozide a carcinogen particularly dangerous to children and sparked a national panic. Scientists with the American Society of Toxiocology noted a lack of scientific evidence in Bradley's report and the United States Environmental Protection Agency and Food and Drug Administration issued a joint statement 18 days after Bradley's story aired, declaring apples safe to eat.[29] A trade group of apple growers from Washington sued 60 Minutes after the story aired, but had their claims dismissed after the United States Supreme Court upheld an appeals court ruling that the association failed to disprove Bradley's story.[30] His coverage of Kathleen Willey, who accused Bill Clinton of sexual misconduct in the 1990s, drew criticism for not pushing Willey in his interview, giving her a disproportionate amount of airtime, and leaving out important information from Clinton's attorney Robert Bennett.[31] The integrity of his December 2003 interview with Michael Jackson was also called into question after CBS refused to air a music special unless Jackson discussed molestation charges with CBS News. Jackson was paid an undisclosed sum for the special by CBS's entertainment division.[32]

Illness and death

editBradley was diagnosed with lymphocytic leukemia in his later years, keeping the illness secret from many, including colleagues such as Wallace.[14] His health rapidly declined after contracting an infection, but Bradley continued to work, saying that he preferred to die "with [his] boots on".[25] Bradley filed 20 stories in his final year with 60 Minutes, conducting his last interviews with members of the Duke University lacrosse team accused of rape weeks before his death.[33] Bradley died at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan on November 9, 2006, at the age of 65.[34]

More than 2,000 people attended Bradley's funeral service at Riverside Church in New York. Among the attendees were the Reverends Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson, musicians Jimmy Buffett and Wynton Marsalis, journalists Dan Rather, Walter Cronkite, and Charlayne Hunter-Gault, and former U.S. president Bill Clinton.[35] In April 2007, Bradley was honored with a jazz funeral mass and procession at St. Augustine Church during the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.[13]

Legacy

editImpact of journalism

editMorley Safer described the themes of Bradley's reporting as "justice, justice served and justice denied".[19] Bradley's reporting on the AIDS epidemic in Africa has been credited with convincing drug companies to donate and discount drugs to treat the disease. His reporting on psychiatric hospitals in the U.S. prompted federal investigations into the largest chains, and his reporting on the Duke lacrosse team has been credited with ensuring the accused had a fair trial.[20][37] Broadcast on October 15, 2006, the 60 Minutes edition that had Bradley's interview with the Duke lacrosse players had nearly 17 million viewers. It was the ninth-most watched show that week and one of the highest rated episodes of the year.[38] Bradley was seen as an inspiration for Black Americans, with columnist Clarence Page writing:[39]

Mr. Bradley challenged the system. He worked hard and prepared himself. He opened himself to the world and dared the world to turn him away. He wanted to be a lot, and he succeeded. Thanks to him, the rest of us know that we can too.

Salim Muwakkil wrote for The Progressive about Bradley's impact on Black journalists, noting that Bradley "proved blacks not only could do the job, but they could do it with panache".[40] Matt Zoller Seitz, writing for Slant Magazine, said Bradley forced audiences and the television news industry to "accept him on his own terms" and that he "annihilate[d] received wisdom about what it meant to be a professional journalist, a black man and an American".[41]

Philanthropy and honors

editIn 1994, Bradley and the Radio Television News Directors Association Foundation started a scholarship program in his name for journalists of color. It awards $10,000 annually.[2][8] In 2007, he was inducted into the Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia Hall of Fame.[42]

Bradley was named one of the "100 Outstanding American Journalists in the last 100 years" in 2012 by faculty at New York University.[43] In 2015, the Pennsylvania General Assembly renamed City Avenue in Philadelphia "Ed Bradley Way".[44] A mural of Bradley was completed in the city in 2018, and a historical marker was installed in 2021.[45][46][47]

Personal life

editBradley was fond of jazz and hosted Jazz at Lincoln Center on National Public Radio.[48] He performed with Jimmy Buffett and the Neville Brothers and was referred to as "the fifth Neville brother" by the group.[49][50] He was an outdoorsman, and often hiked or skied in his free time.[46]

Bradley married three times, to Diane Jefferson, Priscilla Coolidge, and Patricia Blanchet.[14] He split his time between homes in New York and Colorado.[34]

Awards and recognition

edit| Year | Recognized work | Award / honor | Organization | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Reporting on Cambodian refugees | George Polk Award for Foreign Television Reporting | Long Island University | Won | [51] |

| Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [15] | ||

| "The Boat People" | Edward R. Murrow Award | Overseas Press Club | Won | [6] | |

| News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [6] | ||

| Commendation | British Academy of Film and Television Arts | Won | [6] | ||

| "Blacks in America: With All Deliberate Speed?" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] | |

| "The Boston Goes to China" | George Foster Peabody Award | National Association of Broadcasters | Won | [10] | |

| News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [10] | ||

| Ohio State Award | Ohio State University | Won | [10] | ||

| 1980 | "The Boat People" | Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [52] |

| 1981 | "Blacks in America: With All Deliberate Speed?" | Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [52] |

| 1983 | "Lena" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] |

| "In the Belly of the Beast" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15][6] | |

| 1985 | "Schizophrenia" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [10] |

| 1993 | "Made in China" | Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [15] |

| News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] | ||

| "Caitlin's Story" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] | |

| "Withholding Information" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [53] | |

| 1995 | "Semipalatinsk" | Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [52] |

| News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] | ||

| Reporting on Russian and American military bases | Overseas Press Club Award | Overseas Press Club | Won | [15] | |

| "In the Killing Fields of America" | Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, grand prize | Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights | Won | [18] | |

| 1997 | "Big Man, Big Voice" | George Foster Peabody Award | National Association of Broadcasters | Won | [10] |

| Body of journalism work | Black History Maker Award | Associated Black Charities | Won | [54] | |

| 1998 | "Enter the Jury Room" | Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award | Columbia University | Won | [52] |

| "Town Under Siege" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [55] | |

| 2000 | "Death by Denial" | Peabody Award | National Association of Broadcasters | Won | [56] |

| Lifetime achievement in electronic reporting | Paul White Award | Radio Television Digital News Association | Won | [57] | |

| 2001 | "Timothy McVeigh" | News and Documentary Emmy Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15] |

| "Death by Denial" | Outstanding Investigative Journalism Program | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [58] | |

| "Ten Extraordinary Women" | Outstanding Coverage of a Continuing News Story | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [58] | |

| 2002 | "An American Town" | Outstanding Coverage of a Continuing News Story–Long Form | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [59] |

| "Columbine" | Outstanding Investigative Journalism–Long Form | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [59] | |

| 2003 | Career excellence | Lifetime Achievement Award | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [60] |

| "Unhealthy Diagnosis" | Emmy Award for Business and Financial Reporting | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [61] | |

| "A New Lease on Life" | Outstanding Feature Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15][60] | |

| "The Church on Trial" | Outstanding Coverage of a Continuing News Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [15][60] | |

| Career excellence | Damon Runyon Award for Career Journalistic Excellence | Denver Press Club | Won | [62] | |

| 2004 | "Alice Coles of Bayview" | Outstanding Feature Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [63] |

| 2005 | Career excellence | Lifetime Achievement Award | National Association of Black Journalists | Won | [2] |

| "The Murder of Emmett Till" | Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [64][23] | |

| Body of journalism work | Leonard Zeidenberg First Amendment Award | Radio Television Digital News Association | Won | [65] | |

| 2006 | "First Man" | Outstanding Interview in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [66] |

| Career excellence | Lew Klein Award for Excellence | Temple University | Won | [67] | |

| 2007 | "The Duke Rape case" | George Foster Peabody Award | National Association of Broadcasters | Won | [37] |

| Best Report in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Won | [68] | ||

| "Hunting the Homeless" | Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [69] | |

| Career excellence | Broadcast Pioneers Hall of Fame | Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia | Inducted | [42] | |

| 2017 | "Muhammad Ali: Remembering a Legend" [Note 1][70] | Outstanding Coverage of a Breaking News Story in a News Magazine | Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Nominated | [71] |

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Gold, Matea (November 10, 2006). "Ed Bradley, 65; '60 Minutes' veteran known for cool, calm style won 20 Emmy Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Christian, Margena A. (November 27, 2006). "Remember TV News Giant Ed Bradley". Jet. pp. 61–65. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Schorn, Daniel (November 12, 2006). "'Butch' Bradley, The Early Years". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Beggy, Carol; Shanahan, Mark (January 2, 2008). "A star in the classroom". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ "The Way They Were". Ebony. March 1991. p. 106. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Holmes, Patricia (1999). "Ed Bradley". In Murray, Michael D. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Television News. Phoenix, Arizona: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-57356-108-2. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Jacques (November 9, 2006). "Ed Bradley, Veteran CBS Newsman, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Roseboro, Marilyn L. (2011). Smith, Jessie Carney (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture, vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-313-35797-8. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Johnson, Peter (November 10, 2006). "Ed Bradley, a news 'natural'". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2024.

He taught in the Philadelphia area and was once an interim principal -- while also volunteering and working part time at Philly radio station WDAS...Bradley was in Philadelphia when riots broke out during the civil rights era, and began calling in stories about them to the radio station...His 1992 prison interview with Mike Tyson drew high ratings.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ed Bradley". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 16, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Curry, Sheree R. (August 1, 2005). "Bradley Lauded for his Lifetime of Journalism". TelevisionWeek. Vol. 24, no. 31. Los Angeles, Calif.: Crain Communications. pp. 12, 14. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Moore, Frazier (November 10, 2006). "Journalism pioneer Ed Bradley dead at 65". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Walker, Dave (May 1, 2007). "Two jazz funerals for Ed Bradley at New Orleans Jazz Fest 2007". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Steinberg, Jacques (November 10, 2006). "Ed Bradley, TV Correspondent, Dies at 65". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Ed Bradley". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Nashawaty, Chris (November 17, 2006). "Legacy: Ed Bradley". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Fearn-Banks, Kathleen (2006). The A to Z of African-American Television. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press. pp. 54, 401–402. ISBN 978-0-8108-6348-4. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Fay, Robert (2005). "Bradley, Edward R.". In Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (eds.). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, vol. 1 (Second ed.). New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-19-522325-5. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Alemany, Jacqueline (November 9, 2016). "Remembering 60 Minutes' Ed Bradley". CBS News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "60 Minutes' Ed Bradley Dead At 65". CBS News. November 10, 2006. Archived from the original on May 17, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Ewey, Melissa (February 1998). "Real Men Wear Earrings". Ebony. pp. 122–124. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Fraser, Kristopher (February 8, 2022). "Let's Take a Moment to Appreciate Late '60 Minutes' Newsman Ed Bradley's Excellent Style". Robb Report. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Norris, Michele (November 9, 2006). "Ed Bradley, a TV Journalism Favorite, Dies". NPR. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Learmonth, Michael (November 9, 2006). "CBS newsman dies at 65". Variety. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Learmonth, Michael (November 21, 2006). "Friends give Ed Bradley a proper sendoff". Variety. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Bradley, Ed (December 5, 2004). "Dylan looks back". 60 Minutes. CBS News. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ "Ed Bradley receives NABJ's Lifetime Achievement Award". Jet. Vol. 108, no. 21. Johnson Publishing. November 21, 2005. p. 24. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Yates, Brock (December 21, 1986). "Audi's Runaway Trouble With the 5000". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Warren, James (March 26, 1989). "How "media stampede" spread apple panic". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 6, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Negin, Elliott (September–October 1996). "The Alar "Scare" Was for Real". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on May 16, 2000. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (March 23, 1998). "Bennett Angry at '60 Minutes'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2000. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Bauder, David (January 17, 2004). "'60 Minutes' takes heat for Jackson interview". Gainesville Sun. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 10, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Palmer, Caroline; Eggerton, John (November 9, 2006). "Journalist Ed Bradley Dead at 65". Broadcasting & Cable. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "'60 Minutes' Correspondent Ed Bradley Has Died". ABC News. November 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ "A tearful farewell to journalism pioneer Ed Bradley". Jet. Vol. 110, no. 23. Johnson Publishing. December 11, 2006. p. 62. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ (December 12, 2006) H.Res. 1084 To honor the contributions and life of Edward R. Bradley at Congress.gov

- ^ a b Gough, Paul J. (April 5, 2007). "'Office,' Bradley among Peabody winners". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Shister, Gail (October 19, 2006). "A '60 Minutes' workhorse is getting hometown honors". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 9, 2006. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ Page, Clarence (November 14, 2006). "The restless role model". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Muwakkil, Salim (November 16, 2006). "Ed Bradley's legacy". The Progressive. Archived from the original on January 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Matt Zoller Seitz (November 12, 2006). "Nothing but a Man: Ed Bradley, 1941 - 2006". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on December 10, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "Ed Bradley". Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "The 100 Outstanding Journalists in the United States in the Last 100 Years". Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. New York University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, Samaria (November 15, 2015). "Ed Bradley Way dedicated to honor legendary journalist". The Philadelphia Tribune. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Natasha (May 16, 2018). "West Philadelphia Mural Powerful Tribute To Legendary CBS News Journalist Ed Bradley". KYW-TV. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Crimmins, Peter (September 30, 2021). "Philly honors '60 Minutes' journalist Ed Bradley with historical marker in his hometown". WHYY-FM. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Afea (October 1, 2021). "Philly honors '60 Minutes' journalist and native son Ed Bradley with historical marker". The Philadelphia Tribune. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "'60 Minutes' correspondent Ed Bradley dies". Today. NBC News. Associated Press. November 9, 2006. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Schorn, Daniel (November 12, 2006). "The Personal Side Of Ed Bradley". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Wallace, Mike; Rooney, Andy; Kroft, Steve; Hewitt, Don; Schieffer, Bob (November 9, 2006). "Ed Bradley Remembered; Interview With Virginia Senator-Elect Jim Webb". Larry King Live (transcript). Interviewed by Larry King. CNN. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Past Winners: The George Polk Awards". George Polk Awards. Long Island University. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Awards". Columbia University. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "ABC, PBS lead news Emmy nominees". Variety. July 22, 1993. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Sydney Poitier, Jessye Norman and Ed Bradley honored at New York's Associated Black Charities Black History Makers awards dinner". Jet. Vol. 91, no. 15. Johnson Publishing. March 3, 1997. pp. 52–53. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Katz, Richard (July 23, 1998). "PBS tops noms for news Emmys". Variety. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "60 Minutes II: Death by Denial". The Peabody Awards. Archived from the original on October 24, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Paul White Award". Radio Television Digital News Association. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "The 22nd Annual News and Documentary Emmy Award Nominations" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. August 24, 2001. pp. 12, 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "23rd Annual News and Documentary Emmy Award Nominations" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. August 16, 2002. pp. 16, 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c "The 24th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. August 11, 2003. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (December 5, 2003). "Emmy has eye for CBS News". Variety. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Damon Runyon Award". Denver Press Club. February 10, 2020. Archived from the original on October 24, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "The 25th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "The 26th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. July 7, 2005. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Past Honorees". Radio Television Digital News Association. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Schorn, Daniel (September 26, 2006). "'48 Hours' Wins Emmy For 'Hostage'". CBS News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Ed Bradley". Lew Klein Awards. Temple University. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Four Emmys For 60 Minutes". CBS News. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Schorn, Daniel (July 19, 2007). "12 Emmy Nominations For "60 Minutes"". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "CBS News' "48 Hours" to present "Muhammad Ali: Remembering A Legend" - CBS News". CBS News. June 4, 2016. Archived from the original on January 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ "38th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards" (PDF). Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2017. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2022.