This article possibly contains original research. (September 2021) |

Colonel Edward Hawkins Cheney CB (4 November 1778 – 3 March 1848) was a 19th-century British soldier and hero of the Battle of Waterloo. His unique claim to fame was that he had five separate horses killed or wounded under him during the battle. His grave is said to be the only equestrian statue within a British church and is probably the only statue showing a dying horse in Britain.[1]

Edward Cheney | |

|---|---|

| Born | 4 November 1778 Derbyshire |

| Died | 3 March 1848 (aged 69) Gaddesby Hall, Leicestershire |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1794–1818 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 2nd Dragoons |

| Battles / wars | |

| Spouse(s) |

Elizabeth Ayre (m. 1811–1818) |

Life

editEdward Hawkins Cheney was born in Derbyshire on 4 November 1778 the second son of Robert Cheney of Meynell Langley. He joined the 2nd Dragoons at the rank of cornet in 1794, serving in Holland under the Duke of York and was severely wounded during the Flanders Campaign. He was promoted to captain in 1803 and Brevet Major in 1812.[2]

His regiment, known as the Royal North British Dragoons, was more commonly known as the Royal Scots Greys due to their choice of pale horses. At Waterloo they stood alongside the 1st Dragoons (Royals) and 6th Dragoons (Inniskillings) all under General Sir William Ponsonby. They only united on 27 May 1815 and were jointly called the Union Brigade totalling around 1000 men.[3]

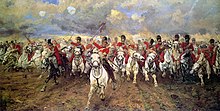

At the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815, the Scots Greys formed part of an echelon and were placed to primarily oppose Marcognet's 3rd Division troops. The net impact was 5000 French casualties and 2000 prisoners, a pivotal impact on the battle overall. The capture of two French eagles, including one by Ensign Ewart, formed part of the action overall. In the heat of the moment Lt Col Hamilton (at that point in command of the Scots Greys) led a suicidal charge on the French artillery accompanied by only around 50 men of the Scots Greys. He, and most of the group, was killed. Sir William Ponsonby the brigade commander was killed soon after.

Cheney found himself promoted in the field to be commander of the regiment and brigade, due to the deaths of the commanding officer and Lt Col Hamilton. At this stage Cheney had been in at least two charges and each time had lost his horse from under him. Now in command he led at least three further charges and had two further horses killed under him and the fifth horse being badly wounded. This unique experience showed an abnormal tenacity and extraordinary bravery. He was in executive charge of the brigade for three hours during the heat of the battle, and led them from the front, but lost command in the administrative reshuffles required after the battle. Although still technically only a captain, he was given the in field rank of Brevet Lt Colonel. The charge and its success, though costly in terms of lives, is seen as one of the critical turning points within the battle, and Cheney is at least partly accountable for this success, and co-ordinated the joint attack of the Scots Greys in support of the Gordon Highlanders, a predominantly Scottish attack.[4]

He retired on half pay in 1818 following the death of his wife (which broke his spirit). He inherited Gaddesby Hall near Melton Mowbray on the death of his father-in-law John Ayre.[5] He died at Gaddesby Hall on 3 March 1848.[6]

He is buried in Gaddesby Parish Church (St Luke's) with his wife. A magnificent tomb depicts his moment of glory where the fifth horse falls below him, shot through the neck. Low relief panels on the sarcophagus base show Ensign Ewart capturing the French regimental standard, the other significant event in the same action. The tomb was sculpted by Joseph Gott.[7]

The monument, in pale grey marble, is well suited to portray the horse. It is listed at Grade 1 as part of the church.[8] The monument was originally not at the grave, but was moved to the church from the conservatory of Gaddesby Hall in 1917.[9] Nicholas Pevsner described the monument as "more suited to St Paul's Cathedral than to a small village church".[10]

The teeth of the horse have been stained brown through a long-running habit of placing an apple in its mouth at each Harvest Thanksgiving in the church.

Family

editIn 1811 he married Elizabeth (Eliza) Ayre, youngest daughter of John Ayre of Gaddesby Hall. Eliza died in childbirth in May 1818 giving birth to their second son (who did not survive). She was only 32 years old.[11]

They had two sons: Edward Henshaw Cheney (1814-1889) and John Ayre Cheney who died in infancy in 1818. Edward paid for the restoration of the chancel in Gaddesby Parish Church in 1859. Edward was made Sheriff of Leicester in 1886.

Other Recognition

editCheney's Waterloo Medal was acquired by the Regimental Museum of the Royal Scots Greys and is now held at Edinburgh Castle.

The Cheney Arms Inn, a public house in the village of Gaddesby, is named after Cheney.[12]

References

edit- ^ "Captain Edward Hawkins Cheney – A Hero of Waterloo". 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Captain Edward Hawkins Cheney – A Hero of Waterloo". 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Charge of the British Heavy Cavalry". 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Scots Greys at Waterloo. The turning point?". 13 June 2015.

- ^ Waterloo Soldier by Humphrey Perkins School

- ^ Tomb of Edward Cheney, Gaddesby Church

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1859 by Rupert Gunnis

- ^ "Leicestershire War Memorials".

- ^ "Colonel e. H. Cheney, CB".

- ^ Pevsner's Architectural Guide to Britain: Yorkshire

- ^ Grave of Elizabeth Cheney, St Luke's Church, Gaddesby

- ^ "Genuki: Gaddesby, Leicestershire".