Egg tapping, also known as egg fight, egg knocking, knocky eggs or egg pacqueing amongst many names, is a traditional Easter game involving the tapping of the ends of two hard-boiled eggs.

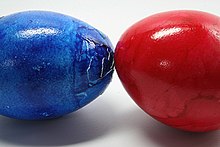

Two tapped eggs: red wins | |

| Players | 2 |

|---|---|

| Chance | High (egg durability) |

Gameplay

editThe rule of the game is simple. One holds a hard-boiled egg and taps the egg of another participant with one's own egg intending to break the other's, without breaking one's own. As with any other game, it has been a subject of cheating; eggs with cement, alabaster and even marble cores have been reported.[1]

History

editIn Christianity, for the celebration of Eastertide, Easter eggs symbolize the empty tomb of Jesus, from which he was resurrected.[2][3][4] Additionally, eggs carry a Trinitarian significance, with shell, yolk, and albumen being three parts of one egg.[5] During Lent, the season of repentance that precedes Easter, eggs along with meat, lacticinia, and wine are foods that are traditionally abstained from, a practice that continues in Eastern Christianity and among certain Western Christian congregations that undertake the Daniel Fast.[6][7] After the forty-day Lenten season concludes and Eastertide begins, eggs may be consumed again, giving rise to various Christian game traditions such as egg tapping, in which the "hard eggshell represented Christ's sealed tomb, and the cracking represented Christ's resurrection."[8]

Egg tapping was practiced in Medieval Europe. The practice was mentioned to have played an important part in the 14th century in Zagreb in relation to Easter.[9][10] A study of folklore quotes an early 15th-century reference from Poland.[1]

In North America, colonial New Amsterdam in the 1600s had the "cracking of eggs", invented by Jonathon and Michael Day on Easter Monday with the winner keeping both eggs.[11]

Egg picking was observed by a British prisoner of war, Thomas Anbury, in Frederick Town, Maryland, in 1781 during the American Revolutionary War. The local custom at that time was to dye the eggs with Logwood or Bloodwood to turn them crimson, which as Anbury observed gave them "great strength".[12] Anbury was near Frederick Town in Maryland, July 11, 1781, when he noted the egg picking custom prevalent there at that time.[13]

By the mid-20th century, a Baltimore, Maryland newspaper, the Evening Sun, would devote an editorial column to discussing street cries, ritual, and techniques for the game.[12] Clarkson cites the Baltimore Evening Sun for 29 March 1933 (editorial page), and in the Sunday Sun for 17 April 1949 (brown section).[14]

In the 21st century, egg cracking is still practiced every Easter by the Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York at the annual Pass Easter Ball.

Competition

editIn Sydney, Australia, Tucanje Jaja (Cracking of the eggs) has been held at Croatian emigrant social club Hrvatski Dom Bosna (Croatian House Bosna) since the social club's inception in 1974. The competition consists of competitors facing off in a knockout-style competition, with the winner being crowned as the last-man-standing. The current champion is Anto "Rog" Beslic, who has won the competition a record seven consecutive times. As a rule, all winners are forced to eat their winning egg following the final, to prove that the egg is not of another material. This rule was introduced in 1984 following several competitiors who were found to have painted wooden eggs in order to progress beyond the group stages.

In England, the game is played between pairs of competitors who repeatedly knock the pointed ends of their eggs together until one of the eggs cracks; the overall winner is the one whose egg succeeds in breaking the greatest number of other eggs. The world egg-jarping championships have been held each Easter Sunday at Peterlee Cricket And Social Club County Durham, England, since 1983. Proceeds from the event are donated to the Macmillan Cancer Support charity.[15]

In many places in Louisiana, egg-tapping is a serious competition event. Marksville claims to be the first to make it into an official event in 1956. In the past some cheaters used guinea hen eggs, which are smaller and have harder shells. Nowadays guinea egg knocking is a separate contest category. Preparation for this contest has turned into a serious science. People now know which breeds of chicken lay harder eggs, and at what time. The chickens must be fed calcium-rich food and have plenty of exercise. Proper boiling of the contest eggs is also a serious issue. Some rules are well known, such as eggs must be boiled tip down, so that the air pocket is on the butt end. There is also a rule that the champions must break and eat their eggs to prove they are not fake.[16][17]

In other cultures and languages

editIn Assam (a state in India) the game is called Koni-juj (Koni = egg; Juj = fight). It is held every year on the day of Goru Bihu (the cattle day) of Rongali Bihu, which falls in mid-April and on the day of Bhogali Bihu, in January.

In Serbia, both coloured eggs and uncoloured Easter eggs are used, as everyone picks an egg to tap or have tapped. Every egg is used until the last person with an unbroken egg is declared the winner, sometimes winning a money pool.

In the Netherlands the game is called eiertikken. Children line up with baskets of coloured eggs and try to break those in another person's basket. Players must only break eggs of the same colour as their own.[18]

In Romania, visitors strike red eggs against one held by the head of the household and exchange the Paschal greeting "Christ has risen!" and "He has risen indeed!" The person who keeps an unbroken egg is said to enjoy the longest life.[18]

In Bulgaria is a similar tradition of egg cracking. Adults and children alike each take an egg, then go around tapping each other. The belief is that the winner of the egg tapping contest (whoever's egg does not crack) will have the best health that year. Additionally, when dyeing the eggs, the first egg must be red. It is typically preserved until the next year as a token of luck and good health.[19][20][21]

Central European Catholics of various nationalities call the tradition epper, likely from the German word Opfer, also used to name the practice, which means 'sacrifice' or, literally, offering.[22]

Rusyns have a tradition of rolling the eggs in a game called čokaty sja (Rusyn: чокати ся). Children roll eggs on the meadows like marbles or tap them by hand. If an egg is cracked, then it belongs to the child whose egg cracked it.[23]

Greeks call the practice tsougrisma (τσούγκρισμα), meaning to clink together.[24]

Armenians call it havgtakhagh (Western Armenian: հաւկթախաղ)[25] or dzvakhagh (Eastern Armenian: ձվախաղ),[26] meaning "egg game".

In Jewish culture, hard-boiled eggs are part of the Passover Seder celebration. Toward the end of the traditional readings, hard-boiled eggs are distributed among guests, who may then play the egg-tapping game.

See also

edit- Egg rolling

- Egg hunt

- Egg dance

- Pace Egg play

- Koni-juj

- Conkers, a similar British game with horse-chestnuts

References

edit- ^ a b Venetia Newall (1971) An Egg at Easter: A Folklore Study, p. 344

- ^ Jordan, Anne (5 April 2000). Christianity. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 9780748753208.

Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to make red Easter eggs that represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world.

- ^ The Guardian, Volume 29. H. Harbaugh. 1878.

Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a stone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ's dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In days past some used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died,-a bloody death.)

- ^ Geddes, Gordon; Griffiths, Jane (22 January 2002). Christian belief and practice. Heinemann. ISBN 9780435306915.

Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other's. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ's resurrection.

- ^ Murray, Michael J.; Rea, Michael C. (20 March 2008). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-139-46965-4.

- ^ "Lent: Daniel Fast Gains Popularity". HuffPost. Religion News Service. February 7, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

In some cases, entire churches do the Daniel Fast together during Lent. The idea strikes a chord in Methodist traditions, which trace their heritage to John Wesley, a proponent of fasting. Leaders in the African Methodist Episcopal Church have urged churchgoers to do the Daniel Fast together, and congregations from Washington to Pennsylvania and Maryland have joined in.

- ^ Hinton, Carla (20 February 2016). "The Fast and the Faithful: Catholic parish in Oklahoma takes up Lenten discipline based on biblical Daniel's diet". The Oklahoman. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

Many parishioners at St. Philip Neri are participating in the Daniel fast, a religious diet program based on the fasting experiences of the Old Testament prophet Daniel. ... participating parishioners started the fast Ash Wednesday (Feb. 10) and will continue through Holy Saturday, the day before Easter Sunday.

- ^ Crump, William D. (22 February 2021). Encyclopedia of Easter Celebrations Worldwide. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4766-4196-6.

Popular egg games consisted of egg-tapping, in which a person attempted to crack an opponent's eggs without cracking his own; and egg-rolling, in which eggs were rolled down chutes, and if an egg hit another eff that had previously rolled down, the owner claimed both eggs. The hard eggshell represented Christ's sealed tomb, and the cracking represented Christ's resurrection.

- ^ Hrvatski informativni centar: Uskrs u Hrvata Archived 2016-04-22 at the Wayback Machine "U starom Zagrebu i njegovoj okolici tucanje jajima upozoravalo je na Uskrs kao prijelomnicu u vremenu pa su tim događajem označavali i vrijeme, bilježeći u dokumentima u 14. stoljeću da se nešto dogodilo "poslije tucanja jaja", tj. poslije Uskrsa."

- ^ Hrvatski uskrsni obicaji: Tucanje jaja, ukrasavanje pisanica i paljenje vuzmice: U nekim tekstovima se navodi da se "tucanje jajima" spominje još u 14. stoljeću u starom Zagrebu i okolici, no prakticira se gotovo u svim dijelovima Hrvatske.

- ^ Peter of New Amsterdam: A Story of Old New York, by James Otis, Living Books Press (July 15, 2007)

- ^ a b Clarkson, Paul S. (December 1956). "Egg-picking". Maryland Historical Magazine. 51 (4): 355. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ Thomas Anbury (1789). Travels through the Interior Parts of America. Vol. II. London. pp. 500–1. as quoted in the Maryland Historical Magazine article. Anbury's book was also published in France, see Ceinture fléchée

- ^ Annie Weston Whitney and Caroline Canfield Bullock (1925). Folklore from Maryland. Memoirs of the American Folklore Society; vol. 18. New York, NY: American Folk-lore Society. p. 117.Cited by Clarkson in their article, see above.

- ^ "Jarpers vie for egg-bashing title", BBC News, 13 April 2009, retrieved 13 April 2009

- ^ Judy Stanford (April 4, 1999). "Egg tapping elevated to a high art in Acadiana". Daily Advertiser. Lafayette, Louisiana. Archived from the original on 2012-05-23.

- ^ "If Your Eggs Are Cracked, Please Step Down: Easter Egg Knocking in Marksville", by Sheri Lane Dunbar, Ph.D. (anthropology), first published in the 1989 Louisiana Folklife Festival booklet

- ^ a b see Polan, Linda; Aileen Cantwell (1983). The Whole Earth Holiday Book. Good Year Books. ISBN 978-0-673-16585-5.

- ^ "Великден – разчупвайте козунаци". capital.bg.

- ^ "Smolyan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ "Вселената на яйцето | E-novinar.com". e-locator.net. Archived from the original on 2021-03-30. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ "Storytelling: About those knocking Easter eggs". Pittsburgh Post- Gazette. March 13, 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Pascha & Customs of the Carpatho-Rusyn People". wirnowski.com.

- ^ "The word tsougrisma means "clinking together" or "clashing." In Greek: τσούγκρισμα, pronounced TSOO-grees-mah." http://greekfood.about.com/od/greeklenteaster/f/tsougrisma.htm Archived 2016-11-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "հաւկթախաղ" [egg game]. www.nayiri.com (in Armenian).

- ^ ""Զատկի" տոնը Հայաստանում և Լեհաստանում (ֆոտոշարք) | Առավոտ – Լուրեր Հայաստանից" (in Armenian).