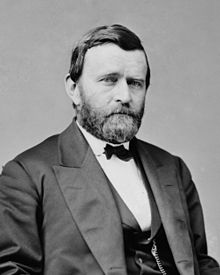

Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku Klux Klan caused widespread violence throughout the South against African Americans. By 1870, all former Confederate states had been readmitted into the United States and were represented in Congress; however, Democrats and former slave owners refused to accept that freedmen were citizens who were granted suffrage by the Fifteenth Amendment, which prompted Congress to pass three Force Acts to allow the federal government to intervene when states failed to protect former slaves' rights. Following an escalation of Klan violence in the late 1860s, Grant and his attorney general, Amos T. Akerman, head of the newly created Department of Justice, began a crackdown on Klan activity in the South, starting in South Carolina, where Grant sent federal troops to capture Klan members. This led the Klan to demobilize and helped ensure fair elections in 1872. He was succeeded by fellow Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, who won the 1876 presidential election.

| |

| Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Republican |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

Rather than develop a cadre of trustworthy political advisers, Grant was self-reliant in choosing his cabinet. He relied heavily on former Army associates, who had a thin understanding of politics and a weak sense of civilian ethics. Numerous scandals plagued his administration, including allegations of bribery, fraud, and cronyism. Grant did respond to corruption charges. At times, he appointed reformers, such as for the prosecution of the Whiskey Ring. Additionally, Grant advanced the cause of Civil Service Reform, more than any president before him, creating America's first Civil Service Commission. In 1872, Grant signed into law an Act of Congress that established Yellowstone National Park, the nation's first National Park.

The United States was at peace with the world throughout Grant's eight years in office, but his handling of foreign policy was uneven. Tensions with Native American tribes in the West continued. Under Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, the Treaty of Washington restored relations with Britain and resolved the contentious Alabama Claims, while the Virginius Affair with Spain was settled peacefully. Grant attempted to annex the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo, but the annexation was blocked by powerful Senator, Charles Sumner. Grant's presidential reputation improved during the 21st Century due to Grant's enforcement of civil rights for blacks.

Background

editUlysses S. Grant was a native of Ohio, born in 1822. After graduating from West Point in 1843 he served in the Mexican–American War. In 1848, Grant married Julia, and had four children. He resigned from the Army in 1854.[1] Upon the start of the American Civil War, Grant returned to the Army in 1861. As a successful Union General, Grant led the Union Armies to defeat the Confederacy. After decisive Union victories at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant as Commanding General of the Union Army. Grant defeated Robert E. Lee, after hard-fought conflicts at the Wilderness and Petersburg. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, and the war ended in 1865.[2]

After the war, Grant served under President Andrew Johnson, and oversaw the enforcement of Reconstruction. In addition, he oversaw conflicts that arose between the indigenous peoples and the settlers. Grant and Johnson became at odds with each other when Grant defended Congressional Reconstruction, which abolished slavery and granted African Americans citizenship, in comparison to Johnson's Reconstruction, which bypassed Congress and was lenient to White southerners.[3]

Election of 1868

editGrant's rise in political popularity among Republicans was based on his successful generalship that defeated Robert E. Lee, and his dramatic break from President Andrew Johnson.[4] His presidential nomination was unopposed and inevitable. The Republican Party delegates unanimously named Grant the presidential candidate at its May convention held in Chicago. House Speaker Schuyler Colfax, was chosen its vice-presidential candidate.[4]

The 1868 Republican Party platform advocated the Enfranchisement of African Americans in the South but kept the issue open in the North. It opposed the use of greenbacks and advocated the use of gold to redeem U.S. bonds. It encouraged immigration and endorsed full rights for naturalized citizens. The platform also favored a radical reconstruction as distinct from the more lenient policy espoused by President Andrew Johnson.[5] In Grant's acceptance letter he said: "Let us have peace."[6][a] These words became the Republican popular mantra.[7]

Grant won the presidential election with an overwhelming Electoral College victory, receiving 214 votes to the Democratic nominee, Horatio Seymour's 80. Grant also received 52.7 percent of the popular vote nationwide. Six southern states controlled by Republicans enhanced Grant's margin of victory, while many ex-Confederates were still prevented from voting.[8]

First term 1869–1873

editInaugural Address 1869

editMathew Brady March 4, 1869

Grant's March 4, 1869, Inaugural speech addressed four priorities. First, Grant said he would approach Reconstruction "calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectional pride; remembering that the greatest good for the greatest number is the object to be obtained." Second, Grant spoke on the nation's financial situation, advocating "a return to a specie basis." Third, Grant spoke on foreign policy, advocating Americans be respected with equality worldwide. Fourth, Grant advocated the passage of the 15th Amendment, that blacks, or former slaves, receive the constitutional right to vote.[9]

Cabinet

editGrant's cabinet choices surprised the nation. Although Grant respectfully listened to political advice, he independently bypassed traditional consultation from prominent Republicans and kept his cabinet choices secret.[10][11] Grant's initial cabinet nominations were met with both criticism and approval.[12] Grant appointed Elihu B. Washburne, Secretary of State, as a friendship courtesy. Washburne served eleven days of office and then resigned. A week later, Grant appointed Washburne Minister to France. Grant appointed the conservative Hamilton Fish, former governor of New York, to replace Washburn.[13] Grant appointed wealthy New York merchant Alexander T. Stewart, Secretary of Treasury, but he was quickly found to be disqualified by a federal law that prohibited anyone in the office from engaging in commerce. When Congress would not amend the law, at Grant's bidding, an embarrassed Grant appointed Massachusetts Congressman George S. Boutwell, to replace Stewart.[14][b] For Secretary of War, Grant appointed his former Army chief of staff John A. Rawlins, however, Rawlins died of tuberculosis in September 1869. To replace Rawlins, six weeks later, Grant appointed former Union Army General William W. Belknap.[16]

For U.S. Attorney General, Grant appointed Massachusetts Supreme Judicial associate justice Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar.[17] For Secretary of Navy, Grant appointed Philadelphia business person Adolph E. Borie. Borie resigned from office on June 25, 1869, finding the job stressful. Borie's noted accomplishment was the racial integration of the Washington Navy Yard. Grant appointed a former New Jersey public prosecutor George M. Robeson, to replace Borie.[18] For Secretary of Interior, Grant appointed former Ohio governor and senator Jacob D. Cox. For Postmaster General, Grant appointed U.S. Senator of Maryland, John A.J. Creswell, who racially integrated the U.S. Post Office.[19]

Tenure of Office Act modified

editIn March 1869, President Grant made it known he desired the Tenure of Office Act (1867) repealed, stating it was a "stride toward a revolution in our free system". The law prevented the president from removing executive officers without Senate approval. Grant believed it was a major curtailment to presidential power.[20] To bolster the repeal effort, Grant declined to make any new appointments except for vacancies, until the law was overturned. On March 9, 1869, the House repealed the law outright, but the Senate Judiciary Committee rejected the bill and only offered Grant a temporary suspension of the law. When Grant objected, the Senate Republican caucus met and proposed allowing the president to have a free hand in choosing and removing his cabinet. The Senate Judiciary Committee wrote the new bill. A muddled compromise was reached by the House and Senate. Grant signed the bill into law on April 5, having gotten virtually everything he wanted.[21]

Reconstruction

editFifteenth Amendment

editGrant worked to ensure ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment approved by Congress and sent to the states during the last days of the Johnson administration. The amendment prohibited the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."[22][23] On December 24, 1869, Grant established federal military rule in Georgia and restored black legislators who had been expelled from the state legislature.[24][25][26] On February 3, 1870, the amendment reached the requisite number of state ratifications (then 27) and was certified as the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[22] Grant hailed its ratification as "a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day".[27] By mid-1870 former Confederate states: Virginia, Texas, Mississippi, and Georgia had ratified the 15th Amendment and were readmitted to the Union.[28]

Department of Justice

editOn June 22, 1870, Grant signed a bill into law passed by Congress that created the Department of Justice and to aid the Attorney General, the Office of Solicitor General. Grant appointed Amos T. Akerman as Attorney General and Benjamin H. Bristow as America's first Solicitor General. Both Akerman and Bristow used the Department of Justice to vigorously prosecute Ku Klux Klan members in the early 1870s. Grant appointed Hiram C. Whitley as director of the new Secret Service Agency in 1869, after he had successfully arrested 12 Klansmen in Georgia who had murdered a leading local Republican official. Whitley used talented detectives who infiltrated and broke up KKK units in North Carolina and Alabama. However, they could not penetrate the main hotbed of KKK activity in upstate South Carolina. Grant sent in Army troops, but Whitley's agents learned they were lying below until the troops were withdrawn. Whitley warned Akerman, who convinced Grant to declare martial law and send in US marshals backed by federal troops to arrest 500 Klansmen; hundreds more fled the state, and hundreds of others surrendered in return for leniency.[29][30]

In the first few years of Grant's first term in office, there were 1000 indictments against Klan members with over 550 convictions from the Department of Justice. By 1871, there were 3000 indictments and 600 convictions with most only serving brief sentences while the ringleaders were imprisoned for up to five years in the federal penitentiary in Albany, New York. The result was a dramatic decrease in violence in the South. Akerman gave credit to Grant and told a friend that no one was "better" or "stronger" than Grant when it came to prosecuting terrorists.[31] Akerman's successor, George H. Williams, in December 1871, continued to prosecute the Klan throughout 1872 until the Spring of 1873 during Grant's second term in office.[32] Williams' clemency and moratorium on Klan prosecutions was due in part to the fact that the Justice Department, having been inundated by Klan outrage cases, did not have the effective manpower to continue the prosecutions.[32]

Naturalization Act of 1870

editOn July 14, 1870, Grant signed into law the Naturalization Act of 1870 that allowed persons of African descent to become citizens of the United States. This revised an earlier law, the Naturalization Act of 1790 that only allowed white persons of good moral character to become U.S. citizens. The law also prosecuted persons who used fictitious names, misrepresentations, or identities of deceased individuals when applying for citizenship.[33]

Force Acts of 1870 and 1871

editTo add enforcement to the 15th Amendment, Congress passed an act that guaranteed the protection of voting rights of African Americans; Grant signed the bill, known as the Force Act of 1870 into law on May 31, 1870. This law was designed to keep the Redeemers from attacking or threatening African Americans. This act placed severe penalties on persons who used intimidation, bribery, or physical assault to prevent citizens from voting and placed elections under Federal jurisdiction.[34]

On January 13, 1871, Grant submitted to Congress a report on violent acts committed by the Ku Klux Klan in the South. On March 23, Grant told a reluctant Congress the situation in the South was dire and federal legislation was needed that would "secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of the law, in all parts of the United States."[35] Grant stated that the U.S. mail and the collection of revenue was in jeopardy.[35] Congress investigated the Klan's activities and eventually passed the Force Act of 1871 to allow prosecution of the Klan. This Act, also known as the "Ku Klux Klan Act" and written by Representative Benjamin Butler, was passed by Congress to specifically go after local units of the Ku Klux Klan. Although sensitive to charges of establishing a military dictatorship, Grant signed the bill into law on April 20, 1871, after being convinced by Secretary of Treasury, George Boutwell, that federal protection was warranted, having cited documented atrocities against the Freedmen.[36][37] This law allowed the president to suspend habeas corpus on "armed combinations" and conspiracies by the Klan. The Act also empowered the president "to arrest and break up disguised night marauders". The actions of the Klan were defined as high crimes and acts of rebellion against the United States.[38][37]

The Ku Klux Klan consisted of local secret organizations formed to violently oppose Republican rule during Reconstruction; there was no organization above the local level. Wearing white hoods to hide their identity the Klan would attack and threaten Republicans. The Klan was strong in South Carolina between 1868 and 1870; South Carolina Governor Robert K. Scott, who was mired in corruption charges, allowed the Klan to rise to power.[39] Grant, who was fed up with their violent tactics, ordered the Ku Klux Klan to disperse from South Carolina and lay down their arms under the authority of the Enforcement Acts on October 12, 1871. There was no response, and so on October 17, 1871, Grant issued a suspension of habeas corpus in all 9 counties in South Carolina. Grant ordered federal troops in the state who then captured the Klan, who were vigorously prosecuted by Att. Gen. Akerman and Sol. Gen. Bristow. With the Klan destroyed other white supremacist groups would emerge, including the White League and the Red Shirts.[34]

Amnesty Act of 1872

editTexas was readmitted into the Union on March 30, 1870, Mississippi was readmitted on February 23, 1870, and Virginia on January 26, 1870. Georgia became the last Confederate state to be readmitted into the Union on July 15, 1870. All members of the House of Representatives and Senate were seated from the 10 Confederate states that seceded. Technically, the United States was again a united country.[40]

To ease tensions, Grant signed the Amnesty Act of 1872 on May 23, 1872, which gave amnesty to former Confederates. This act allowed most former Confederates, who before the war had taken an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States, to hold elected public office. Only 500 former Confederates remained unpardonable and therefore forbidden to hold elected public office.[41]

Financial affairs

editPublic Credit Act

editOn taking office Grant's first move was signing the Act to Strengthen the Public Credit, which the Republican Congress had just passed. It ensured that all public debts, particularly war bonds, would be paid only in gold rather than in greenbacks. The price of gold on the New York exchange fell to $130 per ounce – the lowest point since the suspension of specie payment in 1862.[42]

Federal wages raised

editOn May 19, 1869, Grant protected the wages of those working for the U.S. Government. In 1868, a law was passed that reduced the government working day to 8 hours; however, much of the law was later repealed allowing day wages to also be reduced. To protect workers Grant signed an executive order that "no reduction shall be made in the wages" regardless of the reduction in hours for the government day workers.[43]

Boutwell reforms

editTreasury Secretary George S. Boutwell reorganized and reformed the United States Treasury by discharging unnecessary employees, started sweeping changes in Bureau of Engraving and Printing to protect the currency from counterfeiters, and revitalized tax collections to hasten the collection of revenue. These changes soon led the Treasury to have a monthly surplus.[44] By May 1869, Boutwell reduced the national debt by $12 million. By September the national debt was reduced by $50 million, which was achieved by selling the growing gold surplus at weekly auctions for greenbacks and buying back wartime bonds with the currency. The New York Tribune wanted the government to buy more bonds and greenbacks and the New York Times praised the Grant administration's debt policy.[44]

During the first two years of the Grant administration with George Boutwell at the Treasury helm expenditures had been reduced to $292 million in 1871 – down from $322 million in 1869. The cost of collecting taxes fell to 3.11% in 1871. Grant reduced the number of employees working in the government by 2,248 persons from 6,052 on March 1, 1869, to 3,804 on December 1, 1871. He had increased tax revenues by $108 million from 1869 to 1872. During his first administration, the national debt fell from $2.5 billion to $2.2 billion.[45]

In a rare case of preemptive reform during the Grant Administration, Brevet Major General Alfred Pleasonton was dismissed for being unqualified to hold the position of Commissioner of Internal Revenue. In 1870, Pleasonton, a Grant appointment, approved an unauthorized $60,000 tax refund and was associated with an alleged unscrupulous Connecticut firm. Treasury Secretary George Boutwell promptly stopped the refund and personally informed Grant that Pleasonton was incompetent to hold office. Refusing to resign on Boutwell's request, Pleasonton protested openly before Congress. Grant removed Pleasonton before any potential scandal broke out.[46]

Gold corner conspiracy

editThe New York gold conspiracy almost dismantled Grant's presidency.[47] In September 1869, financial manipulators Jay Gould and Jim Fisk set up an elaborate scam to corner the New York gold market, buying up all the gold at the same time to drive up the price. The plan was to keep the Government from selling gold, thus driving its price. Grant and Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell found out about the gold market speculation and ordered the sale of $4 million in gold on (Black) Friday, September 23. Gould and Fisk were thwarted, and the price of gold dropped. The effects of releasing gold by Boutwell were disastrous. Stock prices plunged and food prices dropped, devastating farmers for years.[48] Although the financial panic that followed was short-lived, the gold scandal overshadowed Grant's presidency.[47]

Foreign affairs

editGrant was a man of peace, and almost wholly devoted to domestic affairs. There were no foreign-policy disasters, and no wars to engage in. Besides Grant himself, the main players in foreign affairs were the Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Charles Sumner. They had to cooperate to get a treaty ratified. When Sumner stopped Grant's plan to annex Santo Domingo, Grant had his vengeance by systematically destroying Sumner's power and ending his career. Historians have high regard for the diplomatic professionalism, independence, and good judgment of Hamilton Fish. The main issues involved Britain, Canada, Santo Domingo, Cuba, and Spain. Worldwide, it was a peaceful era, with no major wars directly affecting the United States.[49]

The foreign policy of the Administration was generally successful, except for the attempt to annex Santo Domingo. The annexation of Santo Domingo was Grant's effort to create a haven for blacks in the South and was a first step to end slavery in Cuba and Brazil.[50][51] The dangers of a confrontation with Britain on the Alabama question were resolved peacefully, and to the monetary advantage of the United States. Issues regarding the Canadian boundary were easily settled. The achievements were the work of Secretary Hamilton Fish, who was a spokesman for caution and stability. A poll of historians has stated that Secretary Fish was one of the greatest Secretaries of States in United States history.[52] Fish served as Secretary of State for nearly the entire two terms.

Hamilton Fish (1808 – 1893) was a wealthy New Yorker of Dutch descent who served as Governor of New York (1849 to 1850), and United States Senator (1851 to 1857). Historians emphasize his judiciousness and efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation.[53][54] Fish settled the controversial Alabama Claims with Great Britain through his development of the concept of international arbitration.[53] Fish kept the United States out of war with Spain over Cuban independence by coolly handling the volatile Virginius Incident.[53] In 1875, Fish initiated the process that would ultimately lead to Hawaiian statehood, by having negotiated a reciprocal trade treaty for the island nation's sugar production.[53] He also organized a peace conference and treaty in Washington, D.C., between South American countries and Spain.[55] Fish worked with James Milton Turner, America's first African American consul, to settle the Liberian-Grebo war.[56] President Grant said he trusted Fish the most for political advice.[57]

Failed annexation of Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic)

editGrant gave a high priority to protecting and improving the status of Blacks in the United States and tried to annex the Caribbean country of the Dominican Republic as a safety valve for them. Senator Charles Sumner was even more firmly devoted to Black interests and opposed Grant's scheme. Sumner stopped the plan and Grant retaliated by destroying Sumner's power.[58] In 1869, Grant proposed to annex the independent Spanish-speaking black nation of the Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo. Previously in 1868, President Johnson had proposed annexation, but Congress refused. In July 1869 Grant sent Orville E. Babcock and Rufus Ingalls who negotiated a draft treaty with Dominican Republic president Buenaventura Báez. To keep the island nation and Báez secure in power, Grant ordered naval ships to secure the island from invasion and internal insurrection. Báez signed an annexation treaty on November 19, 1869. Secretary Fish drew up a final draft of the proposal and offered $1.5 million to the Dominican national debt, the annexation of Santo Domingo as an American state, the United States' acquisition of the rights for Samaná Bay for 50 years with an annual $150,000 rental, and guaranteed protection from foreign intervention. On January 10, 1870, the Santo Domingo treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification. Grant made the mistake of not building support in Congress or the country at large.[59][60][61]

Not only did Grant believe that the island would be of strategic value to the Navy, particularly Samaná Bay, but also he sought to use it as a bargaining chip in domestic affairs. By providing a haven for the freedmen, he believed that the exodus of black labor would force Southern whites to realize the necessity of such a significant workforce and accept their civil rights. Grant believed the island country would increase exports and lower the trade deficit. He hoped that U.S. ownership of the island would push Spain to abolish slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico, and perhaps Brazil as well.[60] On March 15, 1870, the Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Sumner, recommended against treaty passage. Sumner, the leading spokesman for African American civil rights, believed that annexation would be enormously expensive and involve the U.S. in an ongoing civil war, and would threaten the independence of Haiti and the West Indies, thereby blocking black political progress.[62] On May 31, 1870, Grant went before Congress and urged passage of the Dominican annexation treaty.[60] Strongly opposed to ratification, Sumner successfully led the opposition in the Senate. On June 30, 1870, the Santo Domingo annexation treaty failed to pass the Senate; 28 votes in favor of the treaty and 28 votes against.[63] Grant's cabinet was divided over the Santo Domingo annexation attempt, and Bancroft Davis, assistant to Sec. Hamilton Fish was secretly giving information to Sen. Sumner on state department negotiations.[64]

Warren 1879

Grant was determined to keep the Dominican Republic treaty in the public debate, mentioning Dominican Republic annexation in his December 1870 State of the Union Address. Grant was able to get Congress in January 1871 to create a special Commission to investigate the island.[65] Senator Sumner continued to vigorously oppose and speak out against annexation.[65] Grant appointed Frederick Douglass, an African American civil rights activist, as one of the Commissioners who voyaged to the Dominican Republic.[65] Returning to the United States after several months, the Commission in April 1871, issued a report that stated the Dominican people desired annexation and that the island would be beneficial to the United States.[65] To celebrate the Commission's return, Grant invited the Commissioners to the White House, except Frederick Douglass. African American leaders were upset, and the issue of Douglass not being invited to the White House dinner was brought up during the 1872 presidential election by Horace Greeley.[66] Douglass, however, who was personally disappointed for not being invited to the White House, remained loyal to Grant and the Republican Party.[66] Although the Commission supported Grant's annexation attempt, there was not enough enthusiasm in Congress to vote on a second annexation treaty.[66]

Unable constitutionally to go directly after Sen. Sumner, Grant immediately removed Sumner's close and respected friend, Ambassador, John Lothrop Motley.[67] With Grant's prodding in the Senate, Sumner was finally deposed from the Foreign Relations Committee. Grant reshaped his coalition, known as "New Radicals", working with enemies of Sumner such as Ben Butler of Massachusetts, Roscoe Conkling of New York, and Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, giving in to Fish's demands that Cuba rebels be rejected, and moving his Southern patronage from the radical blacks and carpetbaggers who were allied with Sumner to more moderate Republicans. This set the stage for the Liberal Republican revolt of 1872 when Sumner and his allies publicly denounced Grant and supported Horace Greeley and the Liberal Republicans.[68][69][70][71][60]

A Congressional investigation in June 1870 led by Senator Carl Schurz revealed that Babcock and Ingalls both had land interests in the Bay of Samaná that would increase in value if the Santo Domingo treaty were ratified.[citation needed] U.S. Navy ships, with Grant's authorization, had been sent to protect Báez from an invasion by a Dominican rebel, Gregorio Luperón, while the treaty negotiations were taking place. The investigation had initially been called to settle a dispute between an American businessman Davis Hatch against the United States government. Báez had imprisoned Hatch without trial for his opposition to the Báez government. Hatch had claimed that the United States had failed to protect him from imprisonment. The majority Congressional report dismissed Hatch's claim and exonerated both Babcock and Ingalls. The Hatch incident, however, kept certain Senators from being enthusiastic about ratifying the treaty.[72]

Cuban insurrection

editThe Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the Ten Years' War, gained wide sympathy in the U.S. Juntas based in New York raised money, and smuggled men and munitions to Cuba, while energetically spreading propaganda in American newspapers. The Grant administration turned a blind eye to this violation of American neutrality.[73] In 1869, Grant was urged by popular opinion to support rebels in Cuba with military assistance and to give them U.S. diplomatic recognition. Fish, however, wanted stability and favored the Spanish government, without publicly challenging the popular anti-Spanish American viewpoint. They reassured European governments that the U.S. did not want to annex Cuba. Grant and Fish gave lip service to Cuban independence, called for an end to slavery in Cuba, and quietly opposed American military intervention. Fish worked diligently against popular pressure, and was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the Alabama Claims.[74]

Treaty of Washington

editHistorians have credited the Treaty of Washington for implementing international arbitration to allow outside experts to settle disputes. Grant's able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. Previously, Secretary of State William H. Seward during the Johnson administration first proposed an initial treaty concerning damages done to American merchants by three Confederate warships, CSS Florida, CSS Alabama, and CSS Shenandoah built in Britain. These damages were collectively known as the Alabama Claims. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. shipping, as insurance rates soared, and shippers switched to British ships. Washington wanted the British to pay heavy damages, perhaps including turning over Canada.[75] Later, the U.S. added the British blockade runners to the claims, stating that they were responsible for prolonging the war by two years by smuggling in weapons through the Union blockade to the Confederacy.[76][77]

In April 1869, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected a proposed treaty that paid too little and contained no admission of British guilt for prolonging the war. Senator Charles Sumner spoke up before Congress; publicly denounced Queen Victoria; demanded a huge reparation; and opened the possibility of Canada ceded to the United States as payment. The speech angered the British government, and talks had to be put off until matters cooled down. Negotiations for a new treaty began in January 1871 when Britain sent Sir John Rose to America to meet with Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 9, 1871, in Washington, consisting of representatives from both Britain and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international tribunal would settle the damage amounts; the British admitted regret, not fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers nor that charges of blockade running were included in the treaty. Grant approved and signed the treaty on May 8, 1871; the Senate ratified the Treaty of Washington on May 24, 1871.[78][24]

Active service (1862–1864)

The Tribunal met on neutral territory in Geneva, Switzerland. The panel of five international arbitrators included Charles Francis Adams, who was counseled by William M. Evarts, Caleb Cushing, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded the United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain.[79] Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy".[78] In addition to the $15.5 million arbitration award, the treaty resolved some disputes over borders and fishing rights.[80] On October 21, 1872, William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.[79]

Korean incident

editA primary role of the United States Navy in the 19th century was to protect American commercial interests and open trade to Eastern markets, including Japan and China. Korea was a small independent country that excluded all foreign trade. Washington sought a treaty dealing with shipwrecked sailors after the crew of a stranded American commercial ship was executed. The long-term goal for the Grant Administration was to open Korea to Western markets in the same way Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan in 1854 by a Naval display of military force. On May 30, 1871, Rear Admiral John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron, arrived at the mouth of the Salee River below Seoul. The fleet included the Colorado, one of the largest ships in the Navy with 47 guns, 47 officers, and a 571-man crew. While waiting for senior Korean officials to negotiate, Rogers sent ships out to make soundings of the Salee River for navigational purposes.[81][82]

The American fleet was fired upon by a Korean fort, but there was little damage. Rogers gave the Korean government ten days to apologize or begin talks, but the Royal Court kept silent. After ten days passed, on June 10, Rogers began a series of amphibious assaults that destroyed 5 Korean forts. These military engagements were known as the Battle of Ganghwa. Several hundred Korean soldiers and three Americans were killed. Korea still refused to negotiate, and the American fleet sailed away. The Koreans refer to this 1871 U.S. military action as Shinmiyangyo. Grant defended Rogers in his third annual message to Congress in December 1871. After a change in regimes in Seoul, in 1881, the U.S. negotiated a treaty – the first treaty between Korea and a Western nation.[81]

Native American affairs

editDonehogawa

After the very bloody frontier wars in the 1860s, Grant sought to build a "peace policy" toward the tribes. He emphasized appointees who wanted peace and were favorable toward religious groups. In the end, however, the western warfare grew worse.[83]

Grant declared in his 1869 Inaugural Address that he favored "any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship."[84] In a bold step, Grant appointed his aide General Ely S. Parker, Donehogawa (a Seneca), the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker met some opposition in the Senate until Attorney General Hoar said Parker was legally able to hold the office. The Senate confirmed Parker by a vote of 36 to 12.[85] During Parker's tenure Native wars dropped from 101 in 1869 to 58 in 1870.[86]

Board of Indian Commissioners

editEarly on Grant met with tribal chiefs of the Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw nations who expressed interest to teach "wild" Natives outside their own settled districts farming skills.[87] Grant told the Native chiefs that American settlement would lead to inevitable conflict, but that the "march to civilization" would lead to pacification. On April 10, 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners. Grant appointed volunteer members who were "eminent for their intelligence and philanthropy." The Grant Board was given extensive joint power with Grant, Secretary of Interior Cox, and the Interior Department to supervise the Bureau of Indian Affairs and "civilize" Native Americans. No Natives were appointed to the committee, only European Americans. The commission monitored purchases and began to inspect Native agencies. It attributed much of the trouble in Native country to the encroachment of whites. The board approved of the destruction of Native culture. The Natives were to be instructed in Christianity, agriculture, representative government, and assimilated on reservations.[88]

Marias Massacre

editOn January 23, 1870, the Peace Policy was tested when Major Edward M. Baker senselessly slaughtered 173 Piegan Indians, mostly women, and children, in the Marias Massacre. Public outcry increased when General Sheridan defended Baker's actions. On July 15, 1870, Grant signed Congressional legislation that barred military officers from holding either elected or appointed office or suffering dismissal from the Army. In December 1870, Grant submitted to Congress the names of the new appointees, most of whom were confirmed by the Senate.[89][90][91]

Maȟpíya Lúta

Red Cloud White House visit

editGrant's Peace policy received a boost when the Chief of the Oglala Sioux Red Cloud, Maȟpíya Lúta, and Brulé Sioux Spotted Tail, Siŋté Glešká, arrived in Washington, D.C., and met Grant at the White House for a bountiful state dinner on May 7, 1870. Red Cloud, at a previous meeting with Secretary Cox and Commissioner Parker, complained that promised rations and arms for hunting had not been delivered. Afterward, Grant and Cox lobbied Congress for the promised supplies and rations. Congress responded and on July 15, 1870, Grant signed the Indian Appropriations Act into law that appropriated the tribal monies. Two days after Spotted Tail urged the Grant administration to keep white settlers from invading Native reservation land, Grant ordered all Generals in the West to "keep intruders off by military force if necessary".[92] In 1871, Grant signed another Indian Appropriations Act that ended the governmental policy of treating tribes as independent sovereign nations. Natives would be treated as individuals or wards of the state and Indian policies would be legislated by Congressional statutes.[93]

Peace policy

editAt the core of the Peace Policy was placing the western reservations under the control of religious denominations. In 1872, the implementation of the policy involved the allotting of Indian reservations to religious organizations as exclusive religious domains. Of the 73 agencies assigned, the Methodists received fourteen; the Orthodox Friends ten; the Presbyterians nine; the Episcopalians eight; the Roman Catholics seven; the Hicksite Friends six; the Baptists five; the Dutch Reformed five; the Congregationalists three; Christians two; Unitarians two; American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions one; and Lutherans one. Infighting between competitive missionary groups over the distribution of agencies was detrimental to Grant's Peace Policy.[94] The selection criteria were vague, and some critics saw the Peace Policy as violating Native American freedom of religion.[95] In another setback, William Welsh, a prominent merchant, prosecuted the Bureau in a Congressional investigation over malfeasance. Although Parker was exonerated, legislation passed in Congress that authorized the board to approve goods and services payments by vouchers from the Bureau. Parker resigned from office, and Grant replaced Parker with reformer Francis A. Walker.[96]

Domestic affairs

editHolidays law

editOn June 28, 1870, Grant approved and signed legislation that made Christmas, on December 25, a legal federal public holiday in the national capital of Washington, D.C.[97][98][99] According to historian Ron White, Grant did this because of his passion to unify the nation.[100] During the early 19th Century in the United States, Christmas became more of a family-centered activity.[100] Other Holidays, included in the law within Washington, D.C., were New Year, Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving.[97][98] The law affected 5,300 federal employees working in the District of Columbia, the nation's capital.[98] The legislation was meant to adapt to similar laws in states surrounding Washington, D.C., and "in every State of the Union."[98]

Utah territory polygamy

editCharles William Carter 1866–1877

In 1862, during the American Civil War President Lincoln signed into law the Morrill bill that outlawed polygamy in all U.S. Territories. Mormons who practiced polygamy in Utah, for the most part, resisted the Morrill law and the territorial governor.[101]: 301 During the 1868 election, Grant had mentioned he would enforce the law against polygamy. Tensions began as early as 1870, when Mormons in Ogden, Utah began to arm themselves and practice military drilling.[102] By the Fourth of July, 1871 Mormon militia in Salt Lake City, Utah were on the verge of fighting territorial troops; in the end, violence was averted.[103] Grant, however, who believed Utah was in a state of rebellion was determined to arrest those who practiced polygamy outlawed under the Morrill Act.[104] In October 1871 hundreds of Mormons were rounded up by U.S. marshals, put in a prison camp, arrested, and put on trial for polygamy. One convicted polygamist received a $500 fine and three years in prison under hard labor.[105] On November 20, 1871, Mormon leader Brigham Young, in ill health, had been charged with polygamy. Young's attorney stated that Young had no intention to flee the court. Other persons during the polygamy shutdown were charged with murder or intent to kill.[106] The Morrill Act, however, proved hard to enforce since proof of marriage was required for conviction.[101]: 294 Grant personally found polygamy morally offensive. On December 4, 1871, Grant said polygamists in Utah were "a remnant of barbarism, repugnant to civilization, to decency, and to the laws of the United States."[107]

Comstock Act

editIn March 1873, anti-obscenity moralists, led by Anthony Comstock, secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, easily secured passage of the Comstock Act which made it a federal crime to mail articles "for any indecent or immoral use". Grant signed the bill after he was assured that Comstock would personally enforce it. Comstock went on to become a special agent of the Post Office appointed by Secretary James Cresswell. Comstock prosecuted pornographers, imprisoned abortionists, banned nude art, stopped the mailing of information about contraception, and tried to ban what he considered bad books.[108]

Early suffrage movement

editMathew Brady 1865–1880

During Grant's presidency, the early Women's suffrage movement led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton gained national attention. Anthony lobbied for female suffrage, equal gender pay, and protection of property for women who resided in Washington, D.C.[109] In April 1869, Grant signed into law the protection of married women's property from their husbands' debts and the ability for women to sue in court in Washington, D.C.[110] In March 1870 Representative Samuel M. Arnell introduced a bill, coauthored by suffragist Bennette Lockwood, that would give women federal workers equal pay for equal work.[111] Two years later Grant signed a modified Senate version of the Arnell Bill into law.[111] The law required that all federal female clerks would be paid the fully compensated salary; however, lower tiered female clerks were exempted.[112] The law increased women's clerk salaries from 4% to 20% during the 1870s; however, the culture of patronage and patriarchy continued.[112] To placate the burgeoning suffragist movement, the Republicans' platform included that women's rights should be treated with "respectful consideration", while Grant advocated equal rights for all citizens.[113]

Yellowstone and conservation

editAn enduring hallmark of the Grant administration was the creation of Yellowstone, the world's first national park. Organized exploration of the upper Yellowstone River began in fall 1869 when the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition made a month-long journey up the Yellowstone River and into the geyser basins. In 1870, the somewhat more official Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition explored the same regions of the upper Yellowstone and geyser basins, naming Old Faithful and many other park features. Official reports from Lieutenant Gustavus Cheyney Doane and Scribner's Monthly accounts by Nathaniel P. Langford brought increased public awareness to the natural wonders of the region.[114] Influenced by Jay Cooke of the Northern Pacific Railroad and Langford's public speeches about the Yellowstone on the East Coast, geologist Ferdinand Hayden sought funding from Congress for an expedition under the auspices of the U.S. Geological Survey. In March 1871 Grant signed into law Congressional legislation appropriating $40,000 to finance the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. Hayden was given instructions by Grant's Secretary of Interior, Columbus Delano. The expedition party was composed of 36 civilians, mostly scientists, and two military escorts. Among the survey party were an artist Thomas Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson.

Hayden's published reports, magazine articles, along with paintings by Moran and photographs by Jackson convinced Congress to preserve the natural wonders of the upper Yellowstone.[115] On December 18, 1871, a bill was introduced simultaneously in the Senate, by Senator S.C. Pomeroy of Kansas, and in the House of Representatives, by Congressman William H. Clagett of the Montana Territory, for the establishment of a park at the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Hayden's influence on Congress is readily apparent when examining the detailed information contained in the report of the House Committee on Public Lands: "The bill now before Congress has for its objective the withdrawal from settlement, occupancy, or sale, under the laws of the United States a tract of land fifty-five by sixty-five miles, about the sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, and dedicates and sets apart as a great national park or pleasure-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." When the bill was presented to Congress, the bill's chief supporters, ably prepared by Langford, Hayden and Jay Cooke, convinced their colleagues that the region's real value was as a park area, to be preserved in its natural state. The bill was approved by a comfortable margin in the Senate on January 30, 1872, and by the House on February 27.[116]

On March 1, 1872, Grant played his role, in signing the "Act of Dedication" into law. It established the Yellowstone region as the nation's first national park, made possible by three years of exploration by Cook-Folsom-Peterson (1869), Washburn-Langford-Doane (1870), and Hayden (1871). The 1872 Yellowstone Act prohibited fish and game, including buffalo, from "wanton destruction" within the confines of the park. However, Congress did not appropriate funds or legislation for the enforcement against poaching; as a result, Secretary Delano could not hire people to aid tourists or protect Yellowstone from encroachment.[117][118] By the 1880s buffalo herds dwindled to only a few hundred, a majority found mostly in Yellowstone National Park. As the Indian wars ended, Congress appropriated money and enforcement legislation in 1894, signed into law by President Grover Cleveland, that protected and preserved buffalo and other wildlife in Yellowstone.[117] Grant also signed legislation that protected northern fur seals on Alaska's Pribilof Islands. This was the first law in U.S. history that specifically protected wildlife on federally owned land.[119]

End of the buffalo herds

editIn 1872, around two thousand white buffalo hunters working between Kansas, and Arkansas were killing buffalo for their hides by the many thousands. The demand was for boots for European armies, or machine belts attached to steam engines. Acres of land were dedicated solely for drying the hides of the slaughtered buffalo. Native Americans protested at the "wanton destruction" of their food supply. Between 1872 in 1874, the buffalo herd south of the Platte River yielded 4.4 million kills by white hunters, and about 1 million animals killed by Indians.[120] Popular concern for the destruction of the buffalo mounted, and a bill in Congress was passed, HR 921, that would have made buffalo hunting illegal for whites. Taking advice from Secretary Delano, Grant chose to pocket-veto the bill, believing that the demise of the buffalo would reduce Indian wars and force tribes to stay on their respected reservations and to adopt an agricultural lifestyle rather than roaming the plains and hunting buffalo.[117] Ranchers wanted the buffalo gone to open pasture land for their cattle herds. With the buffalo food supply lowered, Native Americans were forced to stay on reservations.[121]

Reforms and scandals

editCivil service commission

editThe reform of the spoils system of political patronage entered the national agenda under the Grant presidency and would take on the fervor of a religious revival.[122] The distribution of federal jobs by Congressional legislators was considered vital for their reelection to Congress.[123] Grant required that all applicants to federal jobs apply directly to the Department heads, rather than the president.[123] Two of Grant's appointments, Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox and Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell put in place examinations in their respected departments advocated by reformers.[124] Grant and all reformers agreed that the prevailing system of appointments was unsound, for it maximized party advantage and minimized efficiency and the nonpartisan interest of good government. Historian John Simon says his efforts at civil service reform were honest, but that they were met with criticism from all sides and were a failure.[125]

Grant was the first president to recommend a professional civil service. He pushed the initial legislation through Congress and appointed the members for the first United States Civil Service Commission. The temporary Commission recommended administering competitive exams and issuing regulations on the hiring and promotion of government employees. Grant ordered their recommendations in effect in 1872; having lasted for two years until December 1874. At the New York Custom House, a port that took in hundreds of millions of dollars a year in revenue, applicants for an entry position now had to pass a written civil service examination. Chester A. Arthur who was appointed by Grant as New York Custom Collector stated that the examinations excluded and deterred unfit persons from getting employment positions.[126] However, Congress, in no mood to reform itself, denied any long-term reform by refusing to enact the necessary legislation to make the changes permanent. Historians have traditionally been divided whether patronage, meaning appointments made without a merit system, should be labeled corruption.[127]

The movement for Civil Service reform reflected two distinct objectives: to eliminate the corruption and inefficiencies in a non-professional bureaucracy and to check the power of President Johnson. Although many reformers after the Election of 1868 looked to Grant to ram Civil Service legislation through Congress, he refused, saying:

Civil Service Reform rests entirely with Congress. If members will give up claiming patronage, that will be a step gained. But there is an immense amount of human nature in the members of Congress, and it is human nature to seek power and use it to help friends. You cannot call it corruption – it is a condition of our representative form of Government.[128]

Grant used patronage to build his party and help his friends. He protected those whom he thought were the victims of injustice or attacks by his enemies, even if they were guilty.[129] Grant believed in loyalty to his friends, as one writer called it the "Chivalry of Friendship".[127]

New York Custom House Ring

editPrior to the presidential election of 1872 two congressional and one Treasury Department investigations took place over corruption at the New York Custom House under Grant collector appointments Moses H. Grinnell and Thomas Murphy. Private warehouses were taking imported goods from the docks and charging shippers storage fees. Grant's friend, George K. Leet, was allegedly involved with exorbitant pricing for storing goods and splitting the profits.[citation needed] Grant's third collector appointment, Chester A. Arthur, implemented Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell's reform to keep the goods protected on the docks rather than private storage.[130]

Star Route Postal Ring

editIn the early 1870s during the Grant Administration, lucrative postal route contracts were given to local contractors on the Pacific Coast and Southern regions of the United States. These were known as Star Routes because an asterisk was given on official Post Office documents. These remote routes were hundreds of miles long and went to the most rural parts of the United States by horse and buggy. In obtaining these highly prized postal contracts, an intricate ring of bribery and straw bidding was set up in the Postal Contract office; the ring consisted of contractors, postal clerks, and various intermediary brokers. Straw bidding was at its highest practice while John Creswell, Grant's 1869 appointment, was Postmaster-General. An 1872 federal investigation into the matter exonerated Creswell, but he was censured by the minority House report. A $40,000 bribe to the 42nd Congress by one postal contractor had tainted the results of the investigation. In 1876, another congressional investigation under a Democratic House shut down the postal ring for a few years.[131]

The Salary Grab

editOn March 3, 1873, Grant signed a law that authorized the president's salary to be increased from $25,000 a year to $50,000 a year and Congressmen's salaries to be increased by $2,500. Representatives also received a retroactive pay bonus for the previous two years of service. This was done in secret and attached to a general appropriations bill. Reforming newspapers quickly exposed the law and the bonus was repealed in January 1874. Grant missed an opportunity to veto the bill and to make a strong statement for good government.[132][133]

Election of 1872

editAs his first term entered its final year, Grant remained popular throughout the nation despite the accusations of corruption that were swirling around his administration. When Republicans gathered for their 1872 national convention he was unanimously nominated for a second term. Henry Wilson was selected as his running mate over scandal-tainted Vice President Schuyler Colfax. The party platform advocated high tariffs and a continuation of Radical Reconstruction policies that supported five military districts in the Southern states.

During Grant's first term, a significant number of Republicans had become completely disillusioned with the party. Weary of the scandals and opposed to several of Grant's policies, split from the party to form the Liberal Republican Party. At the party's only national convention, held in May 1872 New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley was nominated for president, and Benjamin Gratz Brown was nominated for vice president. They advocated civil service reform, a low tariff, and granting amnesty to former Confederate soldiers. They also wanted to end reconstruction and restore local self-government in the South.

The Democrats, who at this time had no strong candidate choice of their own, saw an opportunity to consolidate the anti-Grant vote and jumped on the Greeley bandwagon, reluctantly adopting Greeley and Brown as their nominees.[134] It is the only time in American history when a major party endorsed the candidate of a third party.

While Grant, like incumbent presidents before him, did not campaign, an efficient party organization composed of thousands of patronage appointees, did so on his behalf. Frederick Douglass supported Grant and reminded black voters that Grant had destroyed the violent Ku Klux Klan.[135][136] Greeley embarked on a five-state campaign tour in late September, during which he delivered nearly 200 speeches. His campaign was plagued by misstatements and embarrassing moments.

However, because of political infighting between Liberal Republicans and Democrats, and due to several campaign blunders, the physically ailing Greeley was no match for Grant, who won in a landslide. Grant won 286 of the 352 Electoral College votes and received 55.8 percent of the popular vote nationwide. The President's reelection victory also brought an overwhelming Republican majority into both houses of Congress. Heartbroken after a hard-fought political campaign, Greeley died a few weeks after the election. Out of respect for Greeley, Grant attended his funeral.[134]

Second term 1873–1877

editThe second inauguration of Ulysses Grant's presidency was held on Tuesday, March 4, 1873, commencing the second four-year term of his presidency. Subsequently, the inaugural ball ended early when the food froze. Departing from the White House, a parade escorted Grant down the newly paved Pennsylvania Avenue, which was all decorated with banners and flags, on to the swearing-in ceremony in front of the Capitol building. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the presidential oath of office. This was one of the coldest inaugurations in U.S. history, with the temperature at only 6 degrees at sunrise. After the swearing-in ceremony the inaugural parade commenced down Pennsylvania. The Evening Star observed. "The private stands and windows along the entire route were crowded to excess." The parade consisted of a variety of military units along with marching bands, and civic organizations. The military units, in their fancy regalia, were the most noticeable. Altogether there were approximately 12,000 marchers who participated, including several units of African American soldiers. At the inaugural ball there were some 6,000 people in attendance. Great care was taken to ensure that Grant's inaugural ball would be in spacious quarters and would feature an elegant assortment of appetizers, food, and champagne. A large temporary wooden building was constructed at Judiciary Square to accommodate the event. Grant arrived around 11:30pm and the dancing began.[137][138][139]

It was the only term of Henry Wilson as vice president. Wilson died 2 years, 263 days into this term, and the office remained vacant for the balance of it.

Reconstruction

editGrant was vigorous in his enforcement of the 14th and 15th amendments and prosecuted thousands of persons who violated African American civil rights; he used military force to put down political insurrections in Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.[140] He proactively used military and Justice Department enforcement of civil rights laws and the protection of African Americans more than any other 19th-century president. He used his full powers to weaken the Ku Klux Klan, reducing violence and intimidation in the South. He appointed James Milton Turner as the first African American minister to a foreign nation.[56] Grant's relationship with Charles Sumner, the leader in promoting civil rights, was shattered by the Senator's opposition to Grant's plan to acquire Santo Domingo by treaty. Grant retaliated, firing men Sumner had recommended and having allies strip Sumner of his chairmanship of the Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner joined the Liberal Republican movement in 1872 to fight Grant's reelection.[141]

Conservative resistance to Republican state governments grew after the 1872 elections. With the destruction of the Klan in 1872, new secret paramilitary organizations arose in the Deep South. In Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Louisiana, the Red Shirts and White League operated openly and were better organized than the Ku Klux Klan. Their goals were to oust the Republicans, return Conservative whites to power, and use whatever illegal methods needed to achieve them. Being loyal to his veterans, Grant remained determined that African Americans would receive protection.[142]

Colfax Massacre

editAfter the November 4, 1872, election, Louisiana was a split state. In a controversial election, two candidates were claiming victory as governor. Violence was used to intimidate black Republicans. The fusionist party of Liberal Republicans and Democrats claimed John McEnery as the victor, while the Republicans claimed U.S. Senator William P. Kellogg. Two months later each candidate was sworn in as governor on January 13, 1873. A federal judge ruled that Kellogg was the rightful winner of the election and ordered him and the Republican-based majority to be seated. The White League supported McEnery and prepared to use military force to remove Kellogg from office. Grant ordered troops to enforce the court order and protect Kellogg. On March 4, Federal troops under a flag of truce and Kellogg's state militia defeated McEnery's fusionist party's insurrection.[143]

A dispute arose over who would be installed as judge and sheriff at the Colfax courthouse in Grant Parish. Kellogg's two appointees had seized control of the Court House on March 25 with the aid and protection of black state militia troops. Then on April 13, White League forces attacked the courthouse and massacred 50 black militiamen who had been captured. A total of 105 blacks were killed trying to defend the Colfax courthouse for Governor Kellogg. On April 21, Grant sent in the U.S. 19th Infantry Regiment to restore order. On May 22, Grant issued a new proclamation to restore order in Louisiana. On May 31, McEnery finally told his followers to obey "peremptory orders" of the President. The orders brought a brief peace to New Orleans and most of Louisiana, except, ironically, Grant Parish.[144]

Brooks-Baxter war in Arkansas

editIn the fall of 1872, the Republican party split in Arkansas and ran two candidates for governor, Elisha Baxter and Joseph Brooks. Massive fraud characterized the election, but Baxter was declared the winner and took office. Brooks never gave up; finally, in 1874, a local judge ruled Brooks was entitled to the office and swore him in. Both sides mobilized militia units, and rioting and fighting bloodied the streets. Speculation swirled as to who President Grant would side with – either Baxter or Brooks. Grant delayed, requesting a joint session of the Arkansas government to figure out peacefully who would be the Governor, but Baxter refused to participate. On May 15, 1874, Grant issued a Proclamation that Baxter was the legitimate Governor of Arkansas, and hostilities ceased.[145][146] In the fall of 1874 the people of Arkansas voted out Baxter, and Republicans and the Redeemers came to power.

A few months later in early 1875, Grant announced that Brooks had been legitimately elected back in 1872. Grant did not send in troops, and Brooks never regained office. Instead, Grant appointed him to the high-paying patronage job of US postmaster in Little Rock. Grant's legalistic approach did resolve the conflict peacefully, but it left the Republican Party in Arkansas in total disarray, and further discredited Grant's reputation.[147][148]

Vicksburg riots

editIn August 1874, the Vicksburg city government elected White reform party candidates consisting of Republicans and Democrats. They promised to lower city spending and taxes. Despite such intentions, the reform movement turned racist when the new White city officials went after the county government, which had a majority of African Americans. The White League threatened the life of and expelled Crosby, the black Warren County Sheriff and tax collector. Crosby sought help from Republican Governor Adelbert Ames to regain his position as sheriff. Governor Ames told him to take other African Americans and use force to retain his lawful position. At that time Vicksburg had a population of 12,443, more than half of whom were African American.[149]

On December 7, 1874, Crosby and an African American militia approached Vicksburg. He had said that the Whites were, "ruffians, barbarians, and political banditti".[149] A series of confrontations occurred against white paramilitary forces that resulted in the deaths of 29 African Americans and 2 Whites. The White militia retained control of the County Court House and jail.

On December 21, Grant issued a Presidential Proclamation for the people in Vicksburg to stop fighting. General Philip Sheridan, based in Louisiana for this regional territory, dispatched federal troops, who reinstated Crosby as sheriff and restored the peace. When questioned about the matter, Governor Ames denied that he had told Crosby to use African American militia. On June 7, 1875, Crosby was shot to death by a white deputy while drinking in a bar. The origins of the shooting remained a mystery.[149]

Louisiana revolt and coups

editOn September 14, 1874, the White League and Democratic militia took control of the state house at New Orleans, and the Republican Governor William P. Kellogg was forced to flee. Former Confederate General James A. Longstreet, with 3,000 African American militia and 400 Metropolitan police, made a counterattack on the 8,000 White League troops. Consisting of former Confederate soldiers, the experienced White League troops routed Longstreet's army. On September 17, Grant sent in Federal troops, and they restored the government back to Kellogg. During the following controversial election in November, passions rose high, and violence mixed with fraud were rampant; the state of affairs in New Orleans was becoming out of control. The results were that 53 Republicans and 53 Democrats were elected with 5 remaining seats to be decided by the legislature.[150][151]

Grant had been careful to watch the elections and secretly sent Phil Sheridan in to keep law and order in the state. Sheridan had arrived in New Orleans a few days before the January 4, 1875, legislature opening meeting. At the convention the Democrats again with military force took control of the state building out of Republican hands. Initially, the Democrats were protected by federal troops under Colonel Régis de Trobriand, and the escaped Republicans were removed from the hallways of the state building. However, Governor Kellogg then requested that Trobriand reseat the Republicans. Trobriand returned to the Statehouse and used bayonets to force the Democrats out of the building. The Republicans then organized their own house with their own speakers all being protected by the Federal Army. Sheridan, who had annexed the Department of the Gulf to his command at 9:00 p.m., claimed that the federal troops were being neutral since they had also protected the Democrats earlier.[150]

Civil Rights Act of 1875

editThroughout his presidency, Grant was continually concerned with the civil rights of all Americans, "irrespective of nationality, color, or religion."[152][153] Grant had no role in writing the Civil Rights Act of 1875 but he did sign it a few days before the Republicans lost control of Congress. The new law was designed to allow everyone access to public eating establishments, hotels, and places of entertainment. This was done particularly to protect African Americans who were discriminated across United States. The bill was also passed in honor of Senator Charles Sumner who had previously attempted to pass a civil rights bill in 1872.[154] In his sixth message to Congress, he summed up his own views, "While I remain Executive all the laws of Congress and the provisions of the Constitution ... will be enforced with rigor ... Treat the Negro as a citizen and a voter, as he is and must remain ... Then we shall have no complaint of sectional interference."[34] In the pursued equal justice for all category from the 2009 C-SPAN presidential rating survey Grant scored a 9 getting into the top ten.[155] The Civil Rights Act of 1875 proved a very little value to Blacks. The Justice Department and the federal judges generally refused to enforce it, and the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1883. Historian William Gillette calls it "an insignificant victory."[156]

South Carolina 1876

editDuring the election year of 1876, South Carolina was in a state of rebellion against Republican governor Daniel H. Chamberlain. Conservatives were determined to win the election for ex-Confederate Wade Hampton through violence and intimidation. The Republicans went on to nominate Chamberlain for a second term. Hampton supporters, donning red shirts, disrupted Republican meetings with gun shootings and yelling. Tensions became violent on July 8, 1876, when five African Americans were murdered at Hamburg. The rifle clubs, wearing their Red Shirts, were better armed than the blacks. South Carolina was ruled more by "mobocracy and bloodshed" than by Chamberlain's government.[157]

Black militia fought back in Charleston on September 6, 1876, in what was known as the "King Street riot". The white militia assumed defensive positions out of concern over possible intervention from federal troops. Then, on September 19, the Red Shirts took offensive action by openly killing between 30 and 50 African Americans outside Ellenton. During the massacre, state representative Simon Coker was killed. On October 7, Governor Chamberlain declared martial law and told all the "rifle club" members to put down their weapons. In the meantime, Wade Hampton never ceased to remind Chamberlain that he did not rule South Carolina. Out of desperation, Chamberlain wrote to Grant and asked for federal intervention. The "Cainhoy riot" took place on October 15 when Republicans held a rally at "Brick Church" outside Cainhoy. Blacks and whites both opened fire; six whites and one black were killed. Grant, upset over the Ellenton and Cainhoy riots, finally declared a Presidential Proclamation on October 17, 1876, and ordered all persons, within 3 days, to cease their lawless activities and disperse to their homes. A total of 1,144 federal infantrymen were sent into South Carolina, and the violence stopped; election day was quiet. Both Hampton and Chamberlain claimed victory, and for a while both acted as governor; Hampton took the office in 1877 after President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops and after Chamberlain left the state.[157]

Financial affairs

editPanic of 1873

editBetween 1868 and 1873, the American economy was robust, primarily caused by railroad building, manufacturing expansion, and thriving agriculture production. Financial debt, however, particularly in railroad investment, spread throughout both the private and federal sectors.[158] The market began to break in July 1873 when the Brooklyn Trust Company went broke and closed. Secretary Richardson sold gold to pay for $14 million in federal bonds.[159] Two months later, the Panic of 1873, collapsed the national economy. On September 17, the stock market crashed, followed by the New York Warehouse & Security Company, September 18, and the Jay Cooke & Company, September 19, both going bankrupt. On September 19, Grant ordered Secretary Richardson, Boutwell's replacement, to purchase $10 million in bonds. Richardson complied using greenbacks to expand the money supply. On September 20, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) closed for ten days. Traveling to New York, Grant met with Richardson to consult with bankers, who gave Grant conflicting financial advice.[160]

Returning to Washington, Grant and Richardson sent millions of greenbacks from the treasury to New York to purchase bonds, stopping the purchases on September 24. By the beginning of January 1874, Richardson had issued a total of $26 million greenbacks from the Treasury reserve, into the economy, relieving Wall Street, but not stopping the national Long Depression, that would last 5 years. Thousands of businesses, depressed daily wages by 25% for three years, and brought the unemployment rate up to 14%.[161][162][163]

Inflation bill vetoed and compromise

editGrant and Richardson's mildly inflationary response to the Panic of 1873, encouraged Congress to pursue a more aggressive policy. The legality of releasing greenbacks was presumed to have been illegal. On April 14, 1874, Congress passed the Inflation Bill that set the greenback maximum at $400,000 retroactively legalizing the $26 million reserve greenbacks earlier released by the Treasury. The bill released an additional $18 million in greenbacks up to the original $400,000,000 amount. Going further, the bill authorized an additional $46 million in banknotes and raised their maximum to $400 million.[164] Eastern bankers vigorously lobbied Grant to veto the bill because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors who did business in gold. Most of Grant's cabinet favored the bill in order to secure a Republican election. Grant's conservative Secretary of State Hamilton Fish threatened to resign if Grant signed the bill. On April 22, 1874, after evaluating his own reasons for wanting to sign the bill, Grant unexpectedly vetoed the bill against the popular election strategy of the Republican Party because he believed it would destroy the nation's credit.[165][166]

Congress passed a compromise bill, that Grant signed on June 20, 1874. The act legalized the $26 million released by Richardson and set the maximum of greenbacks at $382 million. Up to $55 million in national banknotes would be redistributed from states with an excess to those states that had minimal amounts. The act did little to relieve the national economy[167]

Resumption of Specie Act

editOn January 14, 1875, Grant signed the Resumption of Specie Act, and he could not have been happier; he wrote a note to Congress congratulating members on the passage of the act. The legislation was drafted by Ohio Republican Senator John Sherman. This act provided that paper money in circulation would be exchanged for gold specie and silver coins and would be effective January 1, 1879. The act also implemented that gradual steps would be taken to reduce the number of greenbacks in circulation. At that time there were "paper coin" currency worth less than $1.00, and these would be exchanged for silver coins. Its effect was to stabilize the currency and make the consumers money as "good as gold". In an age without a Federal Reserve system to control inflation, this act stabilized the economy. Grant considered it the hallmark of his administration.[168][169]

Foreign affairs

editForeign affairs were managed peacefully during Grant's second term in office. Historians credit Secretary of State Hamilton Fish with a highly effective foreign policy. Ronald Cedric White says of Grant, "everyone agreed he chose well when he appointed Hamilton Fish secretary of state."[170]

Virginus incident

editOn October 31, 1873, a steamer Virginius, flying the American flag carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection (in violation of American and Spanish law) was intercepted and taken to Cuba. After a hasty trial, the local Spanish officials executed 53 would-be insurgents, eight of whom were United States citizens; orders from Madrid to delay the executions arrived too late. War scares erupted in both the U.S. and Spain, heightened by the bellicose dispatches from the American minister in Madrid, retired general Daniel Sickles. Secretary of State Fish kept a cool demeanor in the crisis, and through investigation discovered there was a question over whether the Virginius ship had the right to bear the United States flag. The Spanish Republic's president Emilio Castelar expressed profound regret for the tragedy and was willing to make reparations through arbitration. Fish negotiated reparations with the Spanish minister Senor Polo de Barnabé. With Grant's approval, Spain was to surrender Virginius, pay an indemnity to the surviving families of the Americans executed, and salute the American flag; the episode ended quietly.[171]

Grant also played a pivotal role in the affair. Grant sent American warships off of Florida and discussed Cuban invasion plans with General Sherman and the War Department. The bluff worked and the Spanish government accepted Grant's negotiated peace terms. Grant messaged Congress the incident was closed and national honor was restored. However, the salute of the American flag by the Spanish Navy was a stickler. When the Spanish returned the Virginus the Spanish Navy did not salute the American flag disputing that the Virginius was not an American-owned ship. The next day Grant's Attorney General George H. Williams ruled that the Virginus U.S. ownership was fraudulent, but the Spanish had no right to capture the ship.[172][173]

Hawaiian free trade treaty

editIn December 1874, Grant held a state dinner at the White House for the King of Hawaii, David Kalakaua, who was seeking the importation of Hawaiian sugar duty-free to the United States.[174] Grant and Fish were able to produce a successful free trade treaty in 1875 with the Kingdom of Hawaii, incorporating the Pacific islands' sugar industry into the United States' economy sphere.[174]

Liberian-Grebo war

editThe U.S. settled the war between Liberia and the native Grebo people in 1876 by dispatching the USS Alaska to Liberia. James Milton Turner, the first African American ambassador from the United States, requested that a warship be sent to protect American property in Liberia, a former American colony. After Alaska arrived, Turner negotiated the incorporation of Grebo people into Liberian society and the ousting of foreign traders from Liberia.[56]

Mexican border raids

editAt the close of Grant's second term in office, Fish had to contend with Indian raids on the Mexican border, due to a lack of law enforcement over the U.S.–Mexican border. The problem would escalate during the Hayes administration, under Fish's successor William Evarts.[175]

Native American affairs

editUnder Grant's Peace policy, wars between settlers, the federal army, and the American Indians had been decreasing from 101 per year in 1869 to a low of 15 per year in 1875.[86] However, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory and the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway, threatened to unravel Grant's Indian policy, as white settlers encroached upon native land to mine for gold.[176]

In his second term of presidential office, Grant's fragile Peace policy came apart. Major General Edward Canby was killed in the Modoc War. Indian wars per year jumped up to 32 in 1876 and remained at 43 in 1877.[86] One of the highest casualty Indian battles that took place in American history was at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.[177] Indian war casualties in Montana went from 5 in 1875, to 613 in 1876 and 436 in 1877.[178]

Modoc War