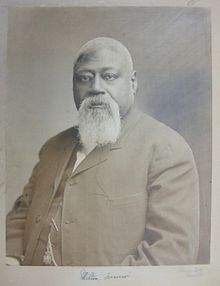

James Milton Turner (c. 1840 – November 1, 1915) was an American political leader, activist, educator, and diplomat during the Reconstruction era. Appointed consul general to Liberia in 1871, he was the first African-American to serve in the U.S. diplomatic corps.

James Milton Turner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Assistant superintendent of Missouri schools | |

| In office After Civil War – pre-1871 | |

| United States Minister to Liberia | |

| In office March 1, 1871 – May 7, 1878 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Preceded by | James W. Mason |

| Succeeded by | John H. Smythe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1840 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | Nov 1, 1915 (75 years old)[1] Ardmore, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (Radical Republicans) Democratic |

| Alma mater | Oberlin College John Berry Meachum's floating Freedom School |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | U.S. Army (Union Army) |

Early life

editTurner was born into slavery in St. Louis, Missouri. As a child, he was sold on the steps of the St. Louis US Courthouse for $50 (equivalent to $1,800 in 2024).[1] His enslaved father, John Turner, was a "horse doctor". Allowed to keep some of his earnings, he eventually purchased freedom for himself and his family.

At fourteen, James Turner attended Oberlin College in Ohio for one term; following his father's death in 1855, Turner had to return to St. Louis to care for his family. Turner attended John Berry Meachum's Floating Freedom School on a steamboat on the Mississippi River, which Meachum had set up to evade the 1847 Missouri law against education of blacks.

Career

editWhen the American Civil War broke out, Turner enlisted in the Union Army and served as body servant for Col. Madison Miller. He was wounded, resulting in a permanent limp.

After the war, Miller's brother-in-law, Missouri Governor Thomas Fletcher, appointed him as assistant superintendent of schools. He had funding from a private religious group, the American Missionary Association based in New England, as well as the War Department's Freedmen's Bureau. He was responsible for setting up 32 schools for black Missourians. He helped establish the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, the first institution of higher education for African Americans in the state. The institute's name was later changed to Lincoln University.[2]

As a politician, Turner, an outspoken member of the Radical Republicans and a leader of the Missouri Equal Rights League, was held in high regard for his oratorical skills.[3] In 1868 he was installed as the principal of Lincoln School, the first school for blacks in Kansas City, Missouri. He was succeeded by J. Dallas Bowser.[4]

In 1871, Turner was appointed as consul general to Liberia by Republican President Ulysses S. Grant. He relocated to Monrovia and held that post until 1878. During this time he was involved in settling the Grebo war.[5]

When he returned to St. Louis, Turner played an important role in helping to resettle black refugees from former Confederate states in the South. He also worked to organize freedmen and people of color free before the Civil War as a political force; they overwhelmingly joined the Republican Party, considered the party of Abraham Lincoln. Turner also took part in relief efforts for African Americans who had left the South for Kansas as part of the Exoduster Movement of 1879. Many of these migrants settled in St. Louis.[6]

In 1881, Turner worked with Hannibal Carter to organize the Freedmen's Oklahoma Immigration Association to promote black homesteading in Oklahoma. As chairman of the Negro National Republican Committee, he proposed nominating US Senator Blanche Bruce, another African American, as the vice presidential candidate on the Republican ticket in 1880.[6]

Turner worked during the last two decades of his life in fighting for the rights of Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw freedmen in the Indian Territory. After the war, the US government had made new treaties with these tribes, which had supported the Confederacy. They required the tribes to offer full citizenship to those freedmen who chose to stay in tribal territory, as the US had done for freedmen in the United States.[7] He successfully lobbied Congress for the nearly 4,000 Cherokee Freedmen to receive $75,000 (US$ 2,543,300 in 2024) from funds that the U.S. government had paid the tribe in 1888 for their land. The Cherokee originally did not want to divide the money for communal lands to include the freedmen.

Death and legacy

editIn late 1915 Turner was in Ardmore, Oklahoma, representing the freedmen in a legal dispute. When a nearby railroad car exploded, the debris cut his left hand. Blood poisoning developed in the wound, and Turner died November 1, 1915, in Ardmore.[8][9][10][11]

The Turner School in the Meacham Park area of Kirkwood, Missouri, was named for Turner. The school opened in 1924 and was renamed after Turner in 1932; it was closed during the 1975–1976 school year[12] in response to a federally mandated directive to address the racial isolation that its African American students were experiencing in the Kirkwood School District.[13]

See also

editBibliography

editNotes

- ^ a b Tulsa daily world 1915, p. 1

- ^ Lawrence O. Christensen, "Schools for Blacks: J. Milton Turner" Missouri Historical Review (1982) 76#2 pp. 121-135..

- ^ Jack 2007

- ^ Coulter 2006, p. 23

- ^ Turner, J. Milton

- ^ a b Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History 1880

- ^ Hine & Jenkins 2001, p. 71

- ^ Dillard 1934, pp. 372–411

- ^ Turner & Dilliard 1941, pp. 1–11

- ^ Kremer 1991

- ^ Appel 2010

- ^ Speer 1998

- ^ U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 1977, pp. 4, 7

References

- Appel, Phyllis (2010). The Missouri Connection: Profiles of the Famous and Infamous. Graystone Enterprises LLC. ISBN 9780984538102. - Total pages: 216

- Christensen, Lawrence O. "Schools for Blacks: J. Milton Turner" Missouri Historical Review (1982) 76#2 pp. 121–135.

- Coulter, Charles Edward (2006). Take Up the Black Man's Burden: Kansas City's African American Communities, 1865-1939. University of Missouri Press.

- Dillard, Irving (October 1934). "James Milton Turner, A Little Known Benefactor of His People". The Journal of Negro History. 19 (4): 372–411. ISSN 1548-1867. JSTOR i347364.

- Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (1880). "Nominating an African-American for President". Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- Hine, Darlene Clark; Jenkins, Earnestine (2001). A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Men's History and Masculinity, Volume 2. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253214607. - Total pages: 482

- Jack, Bryan M. (2007). The St. Louis African American Community and the Exodusters. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826266163. - Total pages: 178

- Kremer, Gary R. (1991). James Milton Turner and the Promise of America: The Public Life of a Post-Civil War Black Leader. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826207807. - Total pages: 245

- Speer, Lonnie R. (1998). "Meacham Park: A History" (PDF). Retrieved April 21, 2019. - Total pages: 116

- Tulsa daily world (November 2, 1915). "Sold as slave ardmore fire is fatal to him". Tulsa daily world. Tulsa, Oklahoma. ISSN 2330-7234. OCLC 4450824. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- Turner, J. Milton; Dilliard, Irving (January 1941). "Dred Scott Eulogized by James Milton Turner: A Historical Observance of the Turner Centenary: 1840-1940". The Journal of Negro History. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/2715047. ISSN 1548-1867. JSTOR 2715047. S2CID 149833894.

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (July 1977). School Desegregation in Kirkwood, Missouri. The Commission. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

Further reading

edit- Christensen, Lawrence O. "Schools for Blacks: J. Milton Turner" Missouri Historical Review (1982) 76#2 pp. 121–135. online

- Walton, Hanes; Rosser, James Bernard; Stevenson, Robert L. (2002). Liberian Politics: The Portrait by African American Diplomat J. Milton Turner. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739103449. - Total pages: 417