Ekajaṭī or Ekajaṭā (Sanskrit: "One Plait Woman"; Wylie: ral gcig ma: one who has one knot of hair),[1] also known as Māhacīnatārā,[2] is one of the 21 Taras. Ekajati is one of the most powerful and fierce protectors of Vajrayana Buddhist mythology.[1][3] According to Tibetan legends[citation needed], her right eye was pierced by the tantric master Padmasambhava so that she could much more effectively help him subjugate Tibetan demons.

Ekajati is also known as "Blue Tārā", "Black Tārā", "Vajra Tārā" or "Ugra Tārā".[1][3] She is generally considered one of the three principal protectors of the Nyingma school along with Rāhula and Vajrasādhu (Wylie: rdo rje legs pa).

Often Ekajati appears as liberator in the mandala of the Green Tara. Along with that, her ascribed powers are removing the fear of enemies, spreading joy, and removing personal hindrances on the path to enlightenment.

Ekajati is the protector of secret mantras and "as the mother of all" represents the ultimate unity. As such, her own mantra is also secret. She is the most important protector of the Vajrayana teachings, especially the Inner Tantras and termas. As the protector of mantra, she supports the practitioner in deciphering symbolic dakini codes and properly determines appropriate times and circumstances for revealing tantric teachings. Because she completely realizes the texts and mantras under her care, she reminds the practitioner of their preciousness and secrecy.[4] Düsum Khyenpa, 1st Karmapa Lama meditated upon her in early childhood.

According to Namkhai Norbu, Ekajati is the principal guardian of the Dzogchen teachings and is "a personification of the essentially non-dual nature of primordial energy."[5]

Dzogchen is the most closely guarded teaching in Tibetan Buddhism, of which Ekajati is a main guardian as mentioned above. It is said that Sri Singha (Sanskrit: Śrī Siṃha) himself entrusted the "Heart Essence" (Wylie: snying thig) teachings to her care. To the great master Longchenpa, who initiated the dissemination of certain Dzogchen teachings, Ekajati offered uncharacteristically personal guidance. In his thirty-second year, Ekajati appeared to Longchenpa, supervising every ritual detail of the Heart Essence of the Dakinis empowerment, insisting on the use of a peacock feather and removing unnecessary basin. When Longchenpa performed the ritual, she nodded her head in approval but corrected his pronunciation. When he recited the mantra, Ekajati admonished him, saying, "Imitate me," and sang it in a strange, harmonious melody in the dakini's language. Later she appeared at the gathering and joyously danced, proclaiming the approval of Padmasambhava and the dakinis.[6]

Origin

editEkajaṭī is found in both the Buddhist and Hindu pantheons; it is most often asserted that she originated in the Buddhist pantheon but some scholars argue this is not necessarily so.[7][8] It is furthermore believed that Ekajaṭī originated in Tibet, and was introduced from there to Nalanda in the 7th century by (the tantric) Nagarjuna.[2]

It appears that, at least in some contexts, she is treated as an emanation of Akshobhya.[9]

Iconography

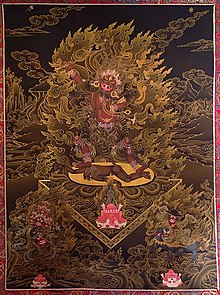

editShe can have dark red or dark blue skin, with a high, red chignon ("she who has but one chignon" is another one of her titles). She has one head, one breast, two arms, and a single eye. However, she can also be depicted with more body parts; up to twelve heads and twenty four arms, with different tantric attributes (sword, kukuri, phurba, blue lotus axe, vajra)

In another form, her hair is arranged in the same single bun with a turquoise forehead curl. This and her other features signify her blazing allegiance to nondualism. Ekajati's single eye gazes into unceasing space, a single fang pierces through obstacles, a single breast "nurtures supreme practitioners as [her] children." She is naked, like awareness itself, except for a garment of white clouds and tiger skin around her waist. The tiger skin is the realized siddha's garb, which signifies fearless enlightenment. She is ornamented with snakes and a garland of human heads. In some representations, she stands on a single leg. Her body is dark in color, brown or deep blue. She stands on a flaming mandala of triangular shape, representing complete awakenment. She is surrounded by a fearsome retinue of mamo demonesses,[clarification needed] who do her bidding in support of the secret teachings, and she emanates a retinue of one hundred ferocious iron wolves from her left hand. For discouraged or lazy practitioners, she is committed to being "an arrow of awareness" to reawaken and refresh them. For defiant or disrespectful practitioners, she is wrathful and threatening, committed to killing their egos and leading them to dharmakaya, or the ultimate realization itself. She holds in her right hand the eviscerated, dripping red heart of those who have betrayed their Vajrayana vows.[4]

In her most common form she holds an axe, drigug (cleaver) or khatvanga (tantric staff) and a skull cup in her hands. In her chignon is a picture of Akshobhya.

Her demeanor expresses determination. With her right foot, she steps upon corpses, symbols of the ego. Her vajra laugh bares a split tongue or a forked tongue and a single tooth. She is adorned with a skull necklace and a tiger and a human skin. She is surrounded by flames representing wisdom.

When Ekajati appears to yogis in hagiographies, she is especially wrathful. She speaks in sharp piercing shrieks, her eye boiling as she gnashes her fang. At times, she appears twice human size, brandishing weapons and served by witches drenched in blood.

Troma Tantra

editThe 'Troma Tantra' or the 'Ngagsung Tromay Tantra', otherwise known as the 'Ekajaṭĭ Khros Ma'i rGyud', focuses on rites of the protector, Ekajati and is subsumed within the Vima Nyingtig.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Alice Getty (1998). The Gods of Northern Buddhism: Their History and Iconography. Courier. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-486-25575-0.

- ^ a b The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India By David Gordon White. pg 65

- ^ a b Michael York (2005). Pagan Theology: Paganism as a World Religion. New York University Press. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-0-8147-9708-2.

- ^ a b Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism By Judith Simmer-Brown. pg 276

- ^ Namkhai Norbu (1986). The Crystal and the Way of Light. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 1-55939-135-9.

- ^ Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism By Judith Simmer-Brown. pg 278

- ^ "The Goddess Mahācīnakrama-Tārā (Ugra-Tārā) in Buddhist and Hindu Tantrism" by Gudrun Bühnemann. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 59, No. 3 (1996), pp. 472

- ^ Kooij, R. K. van. 1974. "Some iconographical data from the Kalikapurana with special reference to Heruka and Ekajata", in J. E. van Lohuizen-de Leeuw and J. M. M. Ubaghs (ed.), South Asian archaeology, 1973. Papers from the second international conference of South Asian archaeologists held in the University of Amsterdam. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1974 pg. 170.

- ^ "The Cult of Jvālāmālinī and the Earliest Images of Jvālā and Śyāma." by S. Settar. Artibus Asiae, Vol. 31, No. 4 (1969), pp. 309

- ^ Thondup, Tulku & Harold Talbott (Editor)(1996). Masters of Meditation and Miracles: Lives of the Great Buddhist Masters of India and Tibet. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Shambhala, South Asia Editions. ISBN 1-57062-113-6 (alk. paper); ISBN 1-56957-134-1, p.362

External links

edit- Ekajati (protector) on HimalayanArt.com - an image of a tanka of Ekajati